Theodore Paleologus

Theodore Paleologus or Palaiologos (Italian: Teodoro Paleologo, Greek: Θεόδωρος Παλαιολόγος, romanized: Theodōros Palaiologos; around 1560 – 21 January 1636) was an Italian nobleman, soldier and assassin of the Paleologus family and possibly the great-great-great-grandson of Thomas Palaiologos. Thomas was the brother of Emperors John VIII (r. 1425–1448) and Constantine XI (r. 1449–1453) and son of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391–1425) of the Byzantine Empire. If his lineage is true, Theodore and his descendants were the last known living male-line descendants of the final Byzantine emperors.

Theodore Paleologus | |

|---|---|

Tombstone of Theodore Paleologus in Landulph | |

| Born | c. 1560 Pesaro, Duchy of Urbino |

| Died | 21 January 1636 (aged c. 76) Landulph, Cornwall, England |

| Buried | St Leonard & St Dilpe Landulph, Cornwall, England |

| Noble family | Paleologus |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Balls |

| Issue

Theodore Paleologus Dorothy Paleologus Mary Paleologus Theodore Paleologus John Theodore Paleologus Elizabeth Paleologus (?) Ferdinand Paleologus | |

| Father | Camilio Paleologus |

| Occupation | Soldier, assassin, Master of the Horse |

Having left his hometown of Pesaro in Italy after being convicted for the attempted murder of a man called Leone Ramusciatti, Theodore lived in exile for many years and became a proficient soldier and hired assassin. He arrived in London in 1597, hired by the authorities of the Republic of Lucca to kill a man called Allesandro Antelminelli. Theodore failed to track down Antelminelli and stayed in England, probably for the rest of his life.

In 1600, he became the henchman of Henry Clinton, the Earl of Lincoln, who at the time was perhaps the most hated nobleman in the entire country. As Master of the Horse, Theodore is thought to have frequently accompanied the Earl on his visits around the country, most of them having to do with the Earl's frequent battles with the law. In the Earl's service, Theodore also met the famous captain and explorer John Smith, whom he gradually helped introduce back into society after Smith had elected to live as a recluse. Theodore's time spent with John Smith might be what inspired Smith to later partake in campaigns against the Ottoman Empire.

While living in Plymouth in 1628, Theodore was employed by the Duke of Buckingham, George Villiers, almost as hated as the now deceased Earl of Lincoln, but the Duke was assassinated soon thereafter. Theodore was then invited by a Sir Nicholas Lower to stay with him at his house, Clifton Hall, in Landulph, Cornwall. There, Theodore lived until his death in 1636. He was buried at Landulph and was survived by five of the six or seven children whom he had with his wife, Mary Balls. Of these children, only Ferdinand Paleologus, who later emigrated to Barbados, had children of his own.

Biography

Exile from Pesaro

Theodore was the son of Camilio Paleologus, who might have been the great-great-grandson of Thomas Palaiologos, a brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine emperor. During his early life, Theodore lived with his two uncles, Camilio's brothers, Scipione and Leonidas Paleologus in the town of Pesaro in Italy.[1] In 1578, the three found themselves embroiled in a scandal as they were convicted for the attempted murder of Leone Ramusciatti, a man who was also originally of Greek descent. Leonidas, Scipione and Theodore failed to kill the man and in an attempt to avoid arrest, they barricaded themselves in a church. Documentation from Pesaro refer to the three as a something akin to a gang and allude to a previous (successful) murder. The fate of Scipione is unknown, but Leonidas was executed. Theodore, who is referred to as a minor (though he was obviously old enough to partake in the crime, probably 16–18 years old) was spared the death penalty and instead banished not only from Pesaro, but from the entire Duchy of Urbino.[2][3]

Work as an assassin

After he was exiled, Theodore is not attested again until nineteen years later, upon his arrival to England in 1597. If Theodore's own later account is to be believed, some of the time in exile was spent fighting for the Protestants in the Netherlands alongside the famous general Maurice of Nassau. Theodore arrived in England as an assassin, hired to track down and kill Allesandro Antelminelli, a 25-year old citizen of the Republic of Lucca in Italy. Antelminelli's father and three brothers had been captured, tortured and executed in Lucca on charges of treason one year prior. Though Antelminelli had been absent during the time of the supposed crime, he had nonetheless been summoned to stand trial for his supposed complicity,[4] and understanding that being at the trial would mean certain execution, he had instead fled to England and assumed the alias of "Ambergio Salvetti", claiming to be From Florence and not Lucca. As "Salvetti", Antelminelli became a comrade of the diplomat and poet Henry Wotton.[5]

Around 40 years old, Theodore was by this point in time well-established as an assassin. At some point between 1578 and 1597, he had been pardoned at Pesaro and had been allowed to return to his hometown, as proven by a letter addressed to "Signor Teodoro Paleologo" in Pesaro, dated 1597.[5] The tone of this letter, signed by the senior magistrate of Lucca, Francesco Andreotti, indicates that Theodore had built an impressive reputation for himself:

Very Magnificent Signor

I have heard with much pleasure that you keep me in your remembrance as I do you, and to show my confidence in you I take the opportunity of employing you in my affairs. By the bearer of this you will be informed what it is that I require, and I beg and request that you will place entire confidence in him. I on my part shall not be ungrateful for besides the usual reward of your work I think of securing you a pension.[5]

The authorities at Lucca had first hired another assassin to kill Antelminelli, Marcantonio Franceotti. Franceotti had been paid 200 lire in advance, but had failed to track down Antelminelli and embarrassed, suggested that Lucca commission a "more seasoned killer". Franceotti recommended Paleologus, and is probably the same person as the one who personally delivered the Lucchese message ("the bearer of this" referred to in the letter). Like Franceotti before him, Paleologus also failed to find and kill Antelminelli, who, despite further attempts to kill him until at least 1627, eventually died of natural causes.[6]

In the service of the Earl of Lincoln

After failing to track down Antelminelli, Theodore appears to have chosen to stay in England. To earn money, he entered into the service of Henry Clinton, the Earl of Lincoln, in 1599. Theodore would spend many years living at the Earl's castle, Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire. Tattershall Castle had once been denounced by King Henry VIII as "one of the most brutal and beastly [castles] of the whole realm" and the town it overlooked, also called Tattershall, was scarcely more than a village by Henry's time, having suffered a drastic depopulation in the late 16th century.[7] Henry Clinton was almost sixty years old and one of the most brutal, feared and hated feudal lords in Britain. Clinton is frequently described as waging war on his neighbors and is often credited with rioting, abduction, arson, sabotage, extortion and perjury. At one point, Clinton even expanded his castle walls into the nearby churchyard.[8]

Clinton officially hired Theodore as his Master of the Horse, but he clearly had intended uses for Theodore beyond the Italian's skills with horses,[9] and presumably knew of Theodore's previous work. Theodore himself probably entered the earl's service due to his advancing age, hoping to find a safer and more stable profession than his many years as a hired killer.[10] The Earl was often at London due to his frequent entanglements with the law, during which Theodore, as Master of the Horse, would likely have accompanied and escorted him.[11]

While staying at Tattershall, Theodore met his future wife, Mary Balls. Mary had been born in Hadleigh, Suffolk c. 1575 (she is attested as 24 years old in 1599) and had no known friends of family outside that town, making her sudden appearance at Tattershall in 1599 somewhat puzzling. The only certain previous link between her family and Tattershall is her father, William Balls, being recorded as a witness to a legal document in Tattershall in 1585. William might thus have been known at the Tattershall household in some capacity.[12]

Mary conceived Theodore's first child c. September 1599 and she married him in Cottingham, East Yorkshire on 1 May 1600, at which point she was several months pregnant. It is possible that the reason for the wedding being so late, only six weeks before the birth of their child, was Theodore accompanying the Earl on one of his law-related trips to London.[13] The ceremony took place in the Church of St. Mary in Cottingham, where the marriage register records the marriage of Thedorus Palelogu and Maria Balle. The couple might have chosen to marry at Cottingham, nearly seventy miles away from Tattershall, due to Cottingham being under the rule of the Duke of Suffolk, Clinton's feudal superior. Because of the relation between the Duke and the Earl, the priest in Cottingham might have avoided asking awkward questions in regards to Mary's pregnancy.[14] Their first child, named Theodore, was baptised on 12 June but died an infant on 1 September.[15][16]

On 14 May, Francis Norreys, the son of Clinton's wife Elizabeth Morrison by a previous marriage, wrote to the Secretary of State, Robert Cecil, in the hope that he would intervene in the Earl's affairs since Clinton had recently ordered that Elizabeth be confined to Tatershall Castle.[17] A passage of Norreys's message reads:

He keeps her docked up like a prisoner, without suffering her either to write or hear from any of her friends, having appointed to guard her an Italian, a man that hath done divers murders in Italy and in the Low Countries, from which he fled to England, from whom, I protest, she has just cause hourly to fear the cutting of her throat.[17]

The Italian murderer referenced is likely to be Theodore. With Clinton pressured to release her as more and more letters describing her situation came in to Cecil, Elizabeth was released later that year.[15]

After having served as a soldier in the Netherlands, John Smith (later the famous captain and explorer) returned home to Lincolnshire in 1600 and tiring of the company of the locals, lived as a recluse and constructed a small wooden house a decent distance from any major town or village. In his own writings, Smith describes how he was befriended by a “Thaedora Polalaga, Rider to Henry Earle of Lincolne” and describes the man as an “excellent horseman” and a “noble Italian gentleman”.[18] Theodore helped Smith become an experienced warrior and might have encouraged him to return to the battlefield, perhaps through tales of the conflicts between his ancestors and the Ottoman Empire.[19][20] In Philip L. Barbour's The Three Worlds of Captain John Smith (1964), Theodore is thought to be the culprit behind filling "John Smith's fancies with further adventurous notions" through legends of the Turks. In Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler's Captain John Smith (2006), Theodore is credited with "igniting the spirit of the Crusaders" in Smith. Smith would later partake in military campaigns against the Ottomans before his more famous ventures in the Americas.[19]

During their time in Lincolnshire, Theodore and Mary had further children. Baptismal records at Tattershall confirms the baptisms of three of their five, possibly six, later children. On 18 August 1606, their daughter Dorothy (identified in the records as "Dorathie, daughter of Theodore Palalogo") was baptized, followed by Theodore ("Theodore Palalogo, son of Theodore Palalogo") on 30 April 1609 and John Theodore ("John Theodore, son of Paleologo Theodore) on 11 July 1611. There is also a partially legible entry for "Elizabeth, daughter of Theo ...", likely another child of Theodore. Since no further records are known of this Elizabeth, she is likely to have died in infancy.[21]

Later years

Earl Henry Clinton died on 29 September 1616.[22] After the Earl's death, there are no further records of Theodore at Tattershall. It is possible that he was quickly evicted by the Earl's son and successor, Thomas Clinton. After 1616, there are no further known records of Theodore until three years later. It is possible that the family lived with Mary's relatives, the Balls family, during this time or that the children were placed in the service of some higher class household, a common practice in regards to adolescents.[23] A further possibility is that Theodore spent much of the time between 1609 and 1621 fighting in the Netherlands during the Eighty Years' War.[16]

Theodore is next attested as living in Plymouth. On 15 June 1619, another son, Ferdinand, was baptized at the Church of St. Andrew in Plymouth, the event being recorded in the baptismal register as the baptism of "Ffardinando son of Theodore Paleologus an Ittalian".[24] The rest of his family was with him at Plymouth, with a document confidently placing Theodore Junior there at least as early as 1623.[25] Theodore was a householder in Plymouth, rated in 1628 at a halfpenny a week. That same year, Theodore, now in his mid-sixties, offered his services to the Duke of Buckingham, George Villiers.[26] Villiers was allegedly an arrogant, corrupt and incompetent member of the nobility and, like Henry Clinton before him, at this point one of the most hated men in all of England.[27] Though the unmarried daughters Dorothy and Mary, and the young Ferdinand, probably lived with Theodore and Mary, the older sons were not at home in 1628, with Theodore Junior, aged 19, making his own life elsewhere and John Theodore probably still being in service.[28]

In Theodore's letter to Villiers, he describes himself as "capable as one who has lived and shed his blood in war since his youth, at the pleasure of the late Prince of Orange, and other diverse English and French lords who have seen and known me and can bear witness" and calls himself a gentleman of a good family, worthy of the name he bears on account of his many accomplishments, but "unlucky in the misfortune experienced by my ancestors and myself".[28] Theodore met the Duke of Buckingham in Plymouth and had seemingly been promised a rather generous employment, but on the 23 August that same year, the Duke was assassinated, leaving Theodore once more without an employer.[29]

Shortly thereafter, Theodore was invited by Sir Nicholas Lower, a rich Cornish squire, to join him at his home in Landulph, Cornwall,[29] probably on account of Theodore's supposedly exalted lineage.[30] Lower's home, Clifton Hall, was divided to accommodate two families after Mary and the Paleologus daughters (and probably Ferdinand) moved in shortly after Theodore, and Theodore probably served the Lower's as a scholar of history and the Greek language, possibly helping to educate their children.[31]

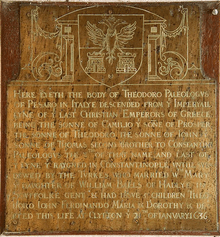

Theodore stayed with his family with Lower at Clifton Hall for the rest of his life.[32] His wife, Mary Balls, was buried in Plymouth on 24 November 1631 and would have been 56 years old at the time of her death.[25] As per the brass plaque which marks his grave in the Church of St Leonard & St Dilpe in Landulph, Theodore died on 21 January 1636.[16][33] The brass plaque prominently displays a coat of arms reminiscent of that of the Palaiologos emperors of Byzantium, displaying the double-headed imperial eagle. In addition to the eagle, the arms prominently features two towers, believed to represent the gates of Rome and Constantinople, and a small crescent at the bottom. The crescent, the meaning of which is unknown, was probably not something used by Theodore himself, likely mistakenly added by Lower, who commissioned the monument.[34] Alternatively, it is possible that the crescent meant to denote Theodore as the second son of his father,[35] but no older son of Camilio is known. The shield is divided into two sections by a line behind the eagle, indicating that it would have had two background colors. Since the brass plaque is without color, it is unknown what these colors were,[34] but it is possible that they were red and white, colors prominently used by the Palaiologan emperors.[36]

The inscription of Theodore's tombstone reads:

Here lyeth the Body of Theodoro Paleologus of Pesaro in Italye descended from ye imperiall lyne of ye last Christian Emperors of Greece, being the sonne of Camilio, the sonne of Prosper, the sonne of Theodoro, the sonne of John, the sonne of Thomas, second brother to Constantine Paleologus, the 8th of that name and last of ye lyne yt raygned in Constantinople untill subdewed by the Turkes, who married with Mary ye Daughter of William Balls of Hadlye in Souffolke, Gent., and had issue 5 children, Theodore, John, Ferdinando, Maria, Dorothy, and departed this life at Clyfton ye 21st of January, 1636.[20][35]

Family and children

With his wife Mary, Theodore had six, possibly seven, children:

- Theodore Paleologus (June – 1 September 1600) – Theodore and Mary's first child, died in infancy.[15]

- Dorothy Paleologus (1606 – 1681) – Also referred to as Dorothea, remained in Landulph after Theodore's death. Dorothy married William Arundel, son of Alexander Arundel, who Nicholas Lower had purchased Clifton Hall from. At the time of the marriage, which took place on 23 December 1656, Dorothy was 50 years old,[37] meaning that it is unlikely that the couple had children.[38] In documents from her marriage, Dorothy is grandly described as "Dorothea Paleologus de stirpe Imperatorum" ("of the imperial stock").[16][37] Dorothy was buried in Landulph in 1681.[38]

- Mary Paleologus (? – 1674) – Also referred to as Maria, remained in Landulph after Theodore's death. Very little is known of Mary and she is the only one of the children (with the exception of the enigmatic Elizabeth) whose birth year is unknown. The sole references to her after Theodore's death is money being bequethed to her in wills; first ten pounds by Nicholas Lower in 1654 and then twenty shillings by her brother Ferdinand in 1670. She was probably never married and was buried in Landulph on 15 May 1674.[37]

- Theodore Paleologus (1609 – 1644) – The oldest son to reach adulthood, Theodore Junior fought for the parliamentarists, or Roundheads, in the English Civil War (1642–1651). He died during the war in 1644, probably of camp fever during the early stages of the Siege of Oxford, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.[16][39]

- John Theodore Paleologus (1611 – ?) – The most enigmatic of the children, John Theodore is thought to have fought for the royalists, or Cavaliers, in the English Civil War, but left England before its conclusion, being attested in Barbados with his younger brother Ferdinand in 1644. Nothing is known of John Theodore after 1644 and his ultimate fate is unknown.[16][40]

- (?) Elizabeth Paleologus – Known only from a partial baptismal record from Tattershall and born at some point between 1611 and 1616, Elizabeth is likely to have been another of Theodore and Mary's daughters. As she is never referenced again after this baptismal record, she is likely to have died in infancy.[21]

- Ferdinand Paleologus (1619 – 2 October 1670) – The youngest son, Ferdinand travelled with John Theodore to Barbados,[40] where he stayed for the rest of his life, becoming one of the elite on the island.[41] He had a son, named Theodore, and was known on Barbados as the "Greek prince from Cornwall".[16] Ferdinand constructed a great house on the island, named Clifton Hall after the house the family had stayed in while in Cornwall,[42] which still stands to this day, recognized as among the greatest on Barbados.[43]

According to some genealogies, Theodore was married to another woman before Mary. This previous marriage would have taken place on 6 July 1593 on the island Chios, his bride being Eudoxia Comnena, a daughter of the nobleman Alexius Comnenus and his wife Helen Cantacuzene (both parents having lastnames of ancient imperial dynasties). Eudoxia was to have died on 6 July 1596, three years after the wedding, in childbirth and the couple's only child was said to have been a girl named Theodora Paleologus, married in 1614 in Naples to "Prince Demetrius Rhodocanakis". Though this genealogy has been accepted by some historians in the past, and notably convinced the Papacy and the British Foreign Office, it originates from forgeries created in the 1860s by the London-based Greek merchant Demetrius Rhodocanakis, who claimed that one of Theodora's descendants was Dr. Constantine Rhodocanakis (a real historical figure), who Demetrius claimed was his ancestor.[44] Demetrius's forgeries were revealed when he published a biography on Constantine Rhodocanakis in 1872, wherein a portrait of Constantine was exposed to actually be a portrait of the author, dressed in a costume, and his genealogy had been thoroughly debunked by the early 20th century.[45]

Legacy

Theodore's grave was accidentally opened in 1795, revealing an oak coffin. Inside, his body was discovered in a good enough state to ascertain that Theodore was far above common height and had possessed an aquiline nose and a long white beard reaching low on his breast.[16][46][47] His well-preserved body means that he had probably been embalmed before being buried.[48] To this day, Theodore's tomb brings many Greek visitors to Landulph. Orthodox memorial services have been observed for him twice, first by the 20th century Archimandrite Barnabas and then in 2007 by Archbishop Gregorios, head of the Orthodox community in Britain.[49] Barnabas's service for Theodore in the late 20th century was the first service of any kind conducted in his name since his burial in 1636.[50] Gregorios's rite, conducted on 18 April 2007, involved draping Theodore's grave in silk ribbons with the colors of the Greek flag, with the Byzantine flag displayed above. This rite was not technically a full traditional memorial rite, since Theodore was not Orthodox, but included chants and incense. The two rites were evocations of ancient Byzantium never before seen in Landulph.[51]

As a somewhat mysterious figure, Theodore has sometimes figured in popular culture. In the novel Sir John Constantine (1906) by Arthur Quiller-Couch, a band of Cornish squires called the "Constantines" are descended from Theodore. The novel is purported to be the 1756 memoirs of Sir John Constantine Paleologus, who with the rest of the Constantines go on several adventures. John Constantine is described as having white hair and an aquiline nose, clearly based on descriptions of the real Theodore Paleologus. In an earlier novella by Quiller-Couch, The Mystery of Joseph Laquedem (1900), a girl named Julie Constantine, also a fictional descendant of Theodore, features in the plot, alongside the actual grave of Theodore himself.[52]

During the First World War, playwright William Price Drury wrote and produced a play called The Emperor's Ring, in which the central plot revolves around a delegation from various states in the Balkans arriving to Landulph to bend the knee to a living descendant of Theodore, an aged miner called Simon Paleol in the play. After a telegram arrives informing the delegation of the death of Simon's only son in the trenches, their hopes are dashed and as Simon grows more and more tired of the delegation hoping for him to take his place on the throne of Greece, he grabs Theodore's old signet ring, a priceless heirloom, and throws it in the Tamar river. The Emperor's Ring was later reworked to a short story, published in 1919 with the title All the King's Men. All the King's Men also features a passage inspired by the opening of Theodore's grave, with the added event of his body crumbling to dust as the grave is opened.[53]

The novel Days Without Number (2003) by Robert Goddard is a thriller with supernatural elements and incorporates fictional modern descendants of Theodore as a central plot element. In the novel, Theodore's Paleologus descendants battle with Bond-style villains through murders, seductions and car and speedboat chases, all in order to find a lost stained glass window with an inscription supposedly containing the date of the Second Coming, preserved by the Knights Templar through the ages.[54]

References

- Hall 2015, p. 42.

- Hall 2015, p. 44.

- Nicol 1974, p. 201.

- Hall 2015, p. 46.

- Hall 2015, p. 47.

- Hall 2015, p. 50.

- Hall 2015, p. 55.

- Hall 2015, p. 57.

- Hall 2015, p. 58.

- Hall 2015, p. 63.

- Hall 2015, p. 97.

- Hall 2015, p. 65.

- Hall 2015, p. 68.

- Hall 2015, p. 69.

- Hall 2015, p. 89.

- Nicol 1974, p. 202.

- Hall 2015, p. 105.

- Hall 2015, p. 99.

- Hall 2015, p. 100.

- Brandow 1983, p. 435.

- Hall 2015, p. 129.

- Hall 2015, p. 142.

- Hall 2015, p. 144.

- Hall 2015, p. 148.

- Hall 2015, p. 149.

- Hall 2015, p. 151.

- Hall 2015, p. 150.

- Hall 2015, p. 152.

- Hall 2015, p. 155.

- Hall 2015, p. 159.

- Hall 2015, p. 160.

- Jago 1817, p. 91.

- Hall 2015, p. 164.

- Hall 2015, p. 165.

- Jago 1817, p. 84.

- Hall 2015, p. 166.

- Hall 2015, p. 180.

- Hall 2015, p. 181.

- Hall 2015, p. 174.

- Hall 2015, p. 179.

- Hall 2015, p. 188.

- Brandow 1983, p. 436.

- Clifton Hall.

- Hall 2015, p. 52.

- Hall 2015, p. 53.

- Hall 2015, p. 167.

- Jago 1817, p. 92–93.

- Hall 2015, p. 168.

- Hall 2015, p. 169.

- Hall 2015, p. 170.

- Hall 2015, p. 18.

- Hall 2015, p. 211.

- Hall 2015, p. 212.

- Hall 2015, p. 214.

Cited bibliography

- Brandow, James C. (1983). Genealogies of Barbados families: from Caribbeana and the Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 0806310049.

- Hall, John (2015). An Elizabethan Assassin: Theodore Paleologus: Seducer, Spy and Killer. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750962612.

- Jago, Vyvyan (1817). "Some Observations on a Monumental Inscription in the Parish Church of Landulph, Cornwall". Archaeologia, Or, Miscellaneous Tracts, Relating to Antiquity. 18.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1974). "Byzantium and England". Balkan Studies. 15 (2): 179–203.

Cited web sources

- "Tour Property". Clifton-Hall. Retrieved 17 October 2019.