Pathans in India

Pathans in India are residents of India who are of ethnic Pashtun ancestry. According to the All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind, there were an estimated 3.2 million people of Pathan descent living in India.[1][2][3] Khan Mohammad Atif, a professor at the University of Lucknow, estimates that "The population of Pathans in India is twice their population in Afghanistan".[4] In the 2011 Census of India, 21,677 individuals reported Pashto as their mother tongue.[5]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3.2 million (2018; figure provided by the All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind)[1][2][3] | |

| Languages | |

"Pathan" is the local Hindustani term for an individual who belongs to the Pashtun ethnic group, or descends from it.[6][7] The term also finds mention among Western sources, mainly in the colonial-era literature of British India.[8][9]

History and culture

The Pathans of India are a community who trace their ancestry to the Pashtun regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan.[10] The Pashtun homeland is located in Central Asia and the northwestern region of South Asia;[11] it roughly stretches from areas south of the Amu River in Afghanistan to west of the Indus River in Pakistan, mainly consisting of southwestern, eastern and some northern and western districts of Afghanistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern Balochistan in Pakistan,[12] with the Durand Line acting as the border between the two countries.[10] The Hindu Kush mountains straddle the north of the region.[6][13] Ethnically, the Pathans are an eastern Iranic group who lived west of the Indo-Aryan ethnicities of the northern Indian subcontinent.[14]

The earlier generations of Indian Pathans spoke their native language Pashto, while some still adhere to the traditional code and Pashtun way of life known as Pashtunwali.[10] In India, the Muslim surname Khan is largely synonymous with and commonly used by Pathans, although not all Khans are necessarily of Pathan descent.[15][16] The female equivalent used by Pathan women is Khanum or Bibi.[16] In the caste system present among medieval Indian Muslim society, the Pathans (historically also known as ethnic 'Afghans') were classified as one of the ashraf castes – those who claimed descent from foreign immigrants,[15] and who claimed the status of nobility by virtue of conquests and Muslim rule in the Indian subcontinent.[17]

Some Pashtuns from the Ghilji tribe historically used to seasonally migrate to India in winter as nomadic merchants. They would buy goods there, and transport these by camel caravan in summer for sale or barter in Afghanistan.[18]

Hindu Pathans

The term "Hindu Pathan" is oft-used as self-identification by some Indian Hindus who hailed from or were born in the predominately Pashtun regions of British India (now Pakistan),[20][21] as well as those who arrived from Afghanistan.[22] The 1947 partition of India led to an exodus of Hindus settled in the former North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) and Baluchistan, which are part of modern Pakistan, into the newly-independent India.[23][24] Notable people from these regions, mainly Peshawar, who identified as Hindu Pathans include the Punjabi-origin independence activist Bhagat Ram Talwar[25] and union minister Mehr Chand Khanna;[26][27] Prithviraj Kapoor,[28] the progenitor of Bollywood's Kapoor family (along with his sons Raj,[29] Shammi[30] and Shashi Kapoor),[29] also of Punjabi descent;[19] his cousin, Surinder Kapoor (father of Anil Kapoor);[31] and film producer F.C. Mehra (father of Umesh Mehra).[32] Pushpa Kumari Bagai writes that the Hindu Pathans in India, especially those who migrated from the Derawali-speaking area of Dera Ismail Khan, had their own unique vegetarian cuisine.[33][34] Tandoori chicken, which was popularised in India by Kundan Lal Gujral, a Punjabi Hindu-"Pathan" chef from Peshawar who moved to Delhi post-partition, is often regarded as a Punjabi-Pathan dish.[35][36] In her historical magnum opus River of Fire, writer Qurratulain Hyder makes reference to Hindu Pathans from the NWFP who were displaced by the partition and settled in India.[37]

Some Hindus who lived in Balochistan prior to 1947, and later migrated to India following the partition, had a highly Pashtunized culture and spoke a form of Pashto or Balochi.[24][38] They identified themselves culturally as Pathans and members of the Kakari tribe. Originating from Quetta and Loralai, they brought their customs and practices with themselves to India, where they became known as the Sheenkhalai (Pashto for "the blue skinned").[24] This name stemmed from a novel tradition their womenfolk practiced, who would adorn their faces, hands and skin with permanent tattoos to enhance their appearance. These decorative, tribal tattoos were considered a form of art and beauty in their culture, however they were looked down upon by other Indians.[24] The women wore a traditional hand-embroidered dress known as the kakrai kameez, similar to a firaq – the upper garment worn by Pashtun females.[24] They also listened to Pashto music and would teach the language to their children.[24] Due to their different culture and appearance, they were often stereotyped and considered Muslims or foreigners by the locals.[24][39] The Sheenkhalai, numbering up to 500 at the time of partition, settled mostly in Rajasthan (in Uniara, Jaipur and Chittorgarh) and Punjab, and adopted Indian culture.[24] In recent years, there have been efforts to revive their indigenous culture. In 2018, former Afghan president Hamid Karzai met members of this community and inaugurated the Sheenkhalai Art Project during the Jaipur Literature Festival.[24] A feature-length documentary titled Sheenkhalai – The Blue Skin produced by Shilpi Batra Adwani, a third-generation Sheenkhalai herself, explores the history and origins of this community and was funded by the India–Afghanistan Foundation.[24]

From the 1950s and onwards, some Pakistani Hindus from Peshawar and surrounding areas moved to India, settling chiefly in Amritsar, Jalandhar, Ludhiana and Firozpur, as well as in Delhi, Rajasthan and other places across India. As of 2005, they numbered over 3,000 families including both Hindus and Sikhs.[40][41] Amritsar itself was home to over 500 Peshawari families, and most of them lived in an area known as the Peshawari Mohalla where they had set up a Hindu temple for the community. They were mainly businesspeople.[40][41] According to the Hindustan Times, around 250 Hindu and Sikh families were living in an area named "Mini Peshawar" near Chheharta in Amritsar as of 2016.[41] Although Peshawar was not as violently affected by communal riots as other regions during the partition, the Peshawari Hindus cited economic issues, security challenges and religious violence as reasons for their emigration after independence. A wave of similar migrations continued in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.[40][42] After living in India for some time, these Hindus are able to secure Indian citizenship. The elderly Peshawari Hindus are distinguishable due to their Peshawari clothing and the Peshawari turban which some of them wear, and they converse in Pashto or the local Peshawari dialect. However, the younger generation is not fluent in these languages.[40][41]

Since the 1970s, thousands of Afghan Hindus have also settled in India while escaping war and persecution. Many of them had lived in the Pashtun areas for generations, spoke Pashto, and practiced a culture that was Pashtun-influenced.[43]

Film and music

The city of Peshawar in the North-West Frontier Province gave birth to several prominent actors in Bollywood.[19][44][28][45][46] Some Indian actors also have ancestry in Balochistan[47][48][49] and Afghanistan.[50] Most of the Khans of Bollywood belong to the Pathan community,[19] such as Shah Rukh Khan,[51] Salman Khan,[16] Aamir Khan[52] and Saif Ali Khan.[51] Actress Madhubala, who is sometimes called the "Marilyn Monroe of Bollywood," was a Yusufzai Pathan.[45] Others, such as the Hindu Pathans of Punjabi origin like the Kapoor family,[19][53][54] or the Hindko-origin[55] Dilip Kumar[56][57][58] and Shah Rukh Khan,[59][60] while not ethnically Pathans, are often referred to as "Pathans" due to their culture and origins in Peshawar.[19][61] The Qissa Khwani Bazaar area is famously the location of the ancestral homes of the Kapoor family, Dilip Kumar and Shah Rukh Khan.[45]

Pathans have contributed to Indian music as well; the sarod, a stringed instrument used in Hindustani classical music, descends from the Pashtun rubab and was invented by the Bangash musical gharana which migrated to India (whose descendants include ustads Sakhawat Hussain, Hafiz Ali Khan, and the latter's son Amjad Ali Khan).[62][63] G. M. Durrani was a noted Bollywood playback singer, music director and radio artist during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s.[64] In pop music, the Pakistani-origin Adnan Sami has been called the "reigning King of Indipop."[19][65]

Literature and media

Pashto in India

Pashto literature thrived in North India from the early 16th century up until the turn of the 19th century, even while Persian remained the dominant language of the region during the Mughal period.[66][67] It was a provincial language spoken mainly by Pashtun administrative and military elites, and other Pashtun settlers and temporary dwellers in India.[66] Extant manuscripts have provided evidence of Pashto verses and poetry emerging from the Ganges region.[66] Pir Roshan, a Sufi who is regarded as one of the earliest Pashto writers, was a Pashtun from Waziristan who was born in Jalandhar.[68] He inspired the Roshani movement which, during the late 16th and 17th centuries, gave rise to prominent Pashto poets and writers in the Indian subcontinent.[68][66] The area forming modern-day Uttar Pradesh was among the few regions in India where Pashto literature continuously developed; Pashtun litterateurs from the Rohilla community produced works in the language up until the late 18th century.[66]

The All India Radio (AIR) operates a Pashto-language service.[69] Pashto was the first external radio service of AIR, broadcasting its inaugural transmission on 1 October 1939 for Pashto-listeners across British India's North-West Frontier Province and Afghanistan. Its purpose was to counter German radio propanda infiltrating Afghanistan, Iran and West Asian nations following the outbreak of World War II.[70][71] The Centre of Persian and Central Asian Studies (CPCAS) at New Delhi's Jawaharlal Nehru University offers bachelor-level degrees in Pashto.[72][73][74]

The language is also used by Afghan Pashtun expatriates living in India.[75]

Politics

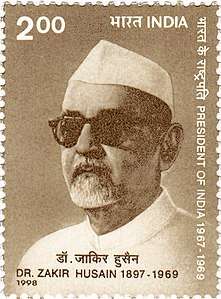

Zakir Husain, an Afridi Pathan, was an economist and politician who served as India's third president from 1967 to 1969. Prior to that, he served as the country's second vice president, and was also the governor of Bihar.[51] His maternal grandson Salman Khurshid served as India's minister for minority affairs, law and justice, and external affairs in successive terms.[76][51] Mohammad Yunus was a career diplomat who served as India's ambassador in various countries, and also became a nominated member of the Rajya Sabha in 1989.[77]

Sport

Pathans have represented the Indian national cricket team both before and after independence. They include Jahangir Khan, a Burki Pathan who played for India between 1932 and 1936, later becoming a cricket administrator in Pakistan.[78] Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, the eighth Nawab of Pataudi, played for both England and India in the 1930s and 1940s, eventually captaining the Indian side in 1946.[79] His son, Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, also played Test cricket as a batsman for India between 1961 and 1975 and became the country's youngest captain when appointed in 1962.[79][51] The all-rounder Salim Durani (who in cricketing records is erroneously referred to as the first Afghan-born Test cricketer, but was born near the Khyber Pass)[80] represented India in Test cricket in the 1960s and 1970s.[79] The brother duo of Yusuf and Irfan Pathan have respectively played for India in the two shorter and all three formats of the game.[81]

In field hockey, Feroze Khan was a gold medalist for India at the 1928 Summer Olympics. He was a Pathan from Jalandhar, and migrated to Pakistan in the early 1950s.[82][83] Ahmed Khan became a gold medalist for India at the 1936 Summer Olympics, while his son Aslam Sher Khan was a member of the Indian squad which won the 1975 Men's Hockey World Cup. They were Pathans from Bhopal.[84][85]

In squash, Abdul Bari was one of India's leading players in the 1940s and represented the country at the 1950 British Open.[86] Yusuf Khan was a ten-time all-India champion[87] who later migrated to Seattle, United States, and turned to coaching several professional players;[88][89] his daughters Shabana and Latasha Khan represented the US.[87][90]

Ghaus Mohammad was the first Indian tennis player to qualify for Wimbledon quarter-finals, in 1939. He was an Afridi Pathan from Malihabad.[91]

Education

Many Afghans flock to India for higher education due to cultural similarities.[92] Each year, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations grants 2,325 scholarships to international students, with six-hundred and seventy-five spots being reserved especially for Afghans.[93]

In India, an increasing number of native students are learning Pashto at academic institutions such as the Jawaharlal Nehru University.[94]

Distribution

Bihar

Delhi

According to Sohail Hashmi, the Peshawari dress and turban were a common site on the streets of Delhi up until the 1960s.[23] The area of Jangpura has long been a hub for Pathan Muslims, possibly due to its proximity to the Nizamuddin Dargah.[23]

Gujarat

Jammu and Kashmir

In July 1954, over 100,000 Pashtun tribespeople living in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir were granted Indian nationality.[95] They are a mostly endogamous, Pashto-speaking community whose ancestors migrated from what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan prior to India's independence.[96] The village of Gotli Bagh in Ganderbal district is home to around 10,000 Pashtuns.[96] The community observes Pashtun customs such as jirga for mediation on disputes, and Pashto television channels like Khyber TV are followed to keep up to date with news in the region.[96] They mostly marry within their community, which has allowed their language and culture to be preserved intact.[96]

Madhya Pradesh

Maharashtra

Mumbai has been home to a Pathan community since the 19th century. They predominately belong to the Yusufzai, Durrani, Ahmadzai, Kakar and Afridi tribes, mostly originating from the tribal areas of northwest Pakistan.[10] Afghanistan has maintained a consulate-general in Bombay since 1915, alluding to the historic presence of Afghans and Pathans in the city.[10]

The Afghan-born Karim Lala was one of the three most influential dons in the Mumbai underworld for decades. As the head of the "Pathan Gang", an organised mafia group of mostly ethnic Pathans involved in the trade of cross-border smuggling, narcotics, bounty hunting (in collusion with Indian businessmen),[97] extortion rackets, gambling and liquor dens, forced evictions, and contract work, Karim Lala wielded significant political clout and was well known to both the elite and the common man of Mumbai.[98][99] It is believed that the famous character of Sher Khan portrayed by Pran in the 1973 film Zanjeer was based on him.[98]

Punjab

The city of Malerkotla is home to a significant population of Punjabi Muslims, some of whom are of Pathan origin.[100] It is notably the only Muslim-majority city in Indian Punjab, since the partition in 1947.[101] The princely Malerkotla State was established and ruled by a Pathan dynasty of Sherwani and Lodi origins.[101][100] The Pathans in Malerkotla were considered an influential group and were principally landowners. Their numbers dwindled after many of them migrated to Pakistan.[100] They are principally divided into the Yusufzai, Lodi, Kakar and Sherwani tribes.[100] The rulers of the state historically shared a harmonious relationship with the Hindus and Sikhs, giving them protection and equal rights as minorities, which is one of the reasons why the city was mostly spared from violence during the partition.[101] Even after independence, members of the royal Pathan family have continued to receive support from Sikh residents in the form of votes during state elections.[100]

Rajasthan

Tamil Nadu

Telangana and Andhra Pradesh

The former Hyderabad State had a Pathan community, and also an organisation known as the Pakhtoon Jirga which looked after the interests of the Pashtuns living within that state.[102]

Uttar Pradesh

See also

References

- Ali, Arshad (15 February 2018). "Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan's great granddaughter seeks citizenship for 'Phastoons' in India". Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

Interacting with mediapersons on Wednesday, Yasmin, the president of All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind, said that there were 32 lakh Phastoons in the country who were living and working in India but were yet to get citizenship.

- "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The News International. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Bhattacharya, Ravik (15 February 2018). "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The Indian Express. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Alavi, Shams Ur Rehman (11 December 2008). "Indian Pathans to broker peace in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times.

Pathans are now scattered across the country, and have pockets of influence in parts of UP, Bihar and other states. They have also shone in several fields, especially Bollywood and sports. The three most famous Indian Pathans are Dilip Kumar, Shah Rukh Khan and Irfan Pathan. “The population of Pathans in India is twice their population in Afghanistan and though we no longer have ties (with that country), we have a common ancestry and feel it’s our duty to help put an end to this menace,” Atif added. Academicians, social activists, writers and religious scholars are part of the initiative. The All India Muslim Majlis, All India Minorities Federation and several other organisations have joined the call for peace and are making preparations for the jirga.

- "Census of India 2011: Language" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Pashtun". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Pashtun, also spelled Pushtun or Pakhtun, Hindustani Pathan, Persian Afghan, Pashto-speaking people residing primarily in the region that lies between the Hindu Kush in northeastern Afghanistan and the northern stretch of the Indus River in Pakistan.

- von Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph (1985). Tribal populations and cultures of the Indian subcontinent. Handbuch der Orientalistik/2,7. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 126. ISBN 90-04-07120-2. OCLC 240120731. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- George Morton-Jack (24 February 2015). The Indian Army on the Western Front South Asia Edition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-107-11765-5.

'Pathan', an Urdu and a Hindi term, was usually used by the British when speaking in English. They preferred it to 'Pashtun', 'Pashtoon', 'Pakhtun' or 'Pukhtun', all Pashtu versions of the same word, which the frontier tribesmen would have used when speaking of themselves in their own Pashtu dialects.

- James William Spain (1963). The Pathan Borderland. Mouton.

The most familiar name in the west is Pathan, a Hindi term adopted by the British, which is usually applied only to the people living east of the Durand.

- Lentin, Sifra (12 December 2019). "Bombay's Pathans: living by a code". Gateway House. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Abubakar Siddique (15 June 2014). The Pashtun Question: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Hurst. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-1-84904-499-8.

- Shane, Scott (5 December 2009). "The War in Pashtunistan". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Joyce A. Quinn; Susan L. Woodward (3 February 2015). Earth's Landscape: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features. ABC-CLIO. pp. 332–. ISBN 978-1-61069-446-9.

- Andrew Simpson (30 August 2007). Language and National Identity in Asia. OUP Oxford. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-19-153308-2.

- James Sadler Hamilton (1994). Sitar Music in Calcutta: An Ethnomusicological Study. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-81-208-1210-9.

- Jasim Khan (27 December 2015). Being Salman. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-81-8475-094-2.

- Ghaus Ansari (1960). Muslim Caste in Uttar Pradesh: A Study of Culture Contact. Ethnographic and Folk Culture Society. p. 32-35. OCLC 1104993.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Ghilzay". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Lentin, Sifra (30 January 2020). "The Khans of Bombay's Hindi film industry". Gateway House. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Reena Nanda (10 February 2018). From Quetta to Delhi: A Partition Story. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-93-86643-44-5.

- Romi Khosla; Nitin Rai (2005). The idea of Delhi. Marg Publications on behalf of the National Centre for the Performing Arts (India). p. 60.

One of the first popular beliefs that was challenged with this narrative was the ethnic description of refugees as "Punjabis." Leela Ram described himself and the group as Hindu Pathans with a distinct Derawali/Frontier identity. But curiously, this was not a sort of opening definition that preceded the rest of the account, rather an insistence that they were Punjabis like everybody else even though they spoke a different language/dialect from the Punjabis.

- Vijay, Tarun (11 December 2019). "From Hindukush to Hindustan, no place for the Hindus?". Times of India. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

And Hindus, once a large majority in Afghanistan, the Afghan Hindus, the Pathan Hindus simply became extinct and turned refugees taking shelter in Germany and other countries. Hindustan never bothers about them. There are some Afghan Hindus living in Delhi. You can meet them to know what it cost them to be here.

- Hashmi, Sohail (15 August 2017). "The Role of Partition in Making Delhi What It Is Today". The Wire. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Wangchuk, Rinchen Norbu; Hegde, Vinayak (8 August 2018). "Hindu Pashtuns: How One Granddaughter Uncovered India's Forgotten Links to Afghanistan". The Better India. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Bose, Mihir (4 April 2017). "Why did Winston Churchill hate the Hindus and prefer the Muslims?". Quartz India. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

Bhagat Ram Talwar, later known as Silver, was the only quintuple spy in World War-II, working for the British, Russians, Germans, Italians, and the Japanese. Silver, who identified as a “Hindu Pathan,” was born and raised in the northwest region of the subcontinent bordering Afghanistan.

- India. Parliament. Lok Sabha (1959). Lok Sabha Debates. Lok Sabha Secretariat. p. 4111.

The Minister of Rehabilitation (Shri Mehr Chand Khanna): I never said that; I object to what has been said by the hon. Member. (Interruption). You live in U.P. and you talk of West Bengal! Shrf S. M. Banerjee: You belong to the Frontier Province and you talk of the whole country. Mr. Deputy-Speaker: Order, order. Shri Mehr Chand Khanna: Bengal. So will I, a Pathan, like to be in Pathan land. So will a Maharashtrian like to be, so will a Gujerati like to be in his own place.

- India. Parliament. Lok Sabha (1970). Lok Sabha Debates. Lok Sabha Secretariat.

I asked, "What is the Pathan doing in Hindu Maha Sabha ?" He stood up and said, "I am a Hindu Pathan and I am trying to do what you and others are doing in Bengal." Then I said he must be Mehr Chand Khanna.

- Khan, M. Ilyas (29 November 2012). "Bollywood's Shah Rukh Khan, Dilip Kumar and the Peshawar club". BBC News. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

Kapoor's father, Prithviraj, was the first self-confessed Hindu "Pathan" from Peshawar to make a mark in Bollywood as an actor and producer.

- Madhu Jain (17 April 2009). Kapoors: The First Family of Indian Cinema. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 75, 214. ISBN 978-81-8475-813-9.

Like his father, Raj Kapoor spent much of his childhood in Peshawar. Born in Samundari on 14 December 1924 he was the only one of Prithviraj's children to speak Pashto and imbibe Pathan culture directly... While Raj Kapoor spent many of his impressionable years in the North West Frontier, for Shashi Kapoor it was just a place his father had left behind when he went to Bombay to become an actor. It was somewhere he went for a holiday as a child, or to attend a family wedding. Being a Pathan was more central to the identity of the eldest brother. Pathaniyat for Shammi Kapoor did not go much beyond a Pathan servant of the family...

- Tejaswini Ganti (2013). Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-415-58384-8.

Shammi Kapoor, a successful star of the 1960s and the younger brother of Raj Kapoor (see chapter 3) reflects on the polyglot nature of Bombay and the Hindi film industry... "I, for one, belong to Peshawar. I'm a Pathan. Someone from Pakistan sent me an email and they said, "How do you qualify as a Pathan? Pathans are only Muslims." So I'm writing to him that Pathan is not a religious group, but a community of people. I come from there...

- Khan, Wajahat S. (8 October 2009). "TalkBack with Wajahat Khan and Anil Kapoor, Episode 33 Part 1". TalkBack with Dawn News. Retrieved 31 May 2020 – via YouTube.

I'm a Pathan's son. My father, my grandfather, they all were Pathans from Peshawar...

- Seta, Keyur (29 July 2018). "FC Mehra: Suspended air force man who became a successful producer". Cinestaan. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

My family hailed from Peshawar [in the erstwhile North West Frontier Province, now in Pakistan] and we are what we call Hindu Pathans," FC Mehra's son, filmmaker Umesh Mehra, said.

- Raza, Munnazzah (25 June 2015). "Zaiqay Frontier Kay: Cookbook in Urdu and Hindi attempts to bring Pakistan and India closer". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Written by the late Pushpa Kumari Bagai, this book is a collection of her special culinary traditions – 80 vegetarian cuisine recipes, each one reflecting the history and culture of the Hindu Pathan community of Dera Ismail Khan.

- "Award-winning Zaiqay Frontier Ke presented to the queen of Bhutan". Daily Times. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

...Pushpa Kumari Bagai, who herself was the custodian and exponent of a very special culinary tradition – the vegetarian cuisine of the Hindu Pathans of Dera Ismail Khan.

- Monish Gujral (5 January 2004). Moti Mahal's Tandoori Trail. Roli Books Private Limited. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-93-5194-023-4.

One of this intrepid breed to whom defeat was a dirty word was Kundan Lal Gujral. He was a Punjabi-Pathan from the North-West Frontier Province. This area, in what later became part of West Pakistan, comprised a unique blend of not only Hindu-Muslim culture but also a Punjabi-Pathan mix.

- Sanghvi, Vir (14 August 2019). "The Taste With Vir: The Tandoori Chicken is a Punjabi bird and we should say it loud". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Qurratulain Hyder; Qurratulʻain Ḥaidar (1999). River of Fire. New Directions. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-8112-1418-6.

The citizens of Lucknow had never heard of Hindu Pathans who were now wandering the lanes of Aminabad, uprooted from the North West Frontier Province.

- George, Anesha (27 January 2019). "See the 'blue-skinned' Pashtun Hindus brought to life in a new film". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Hindu Pashtuns, who are considered Pakistani Muslims by many". BBC Punjabi (in Punjabi). 13 April 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2020 – via YouTube.

- Walia, Varinder (14 April 2005). "Peshawaris strive to keep their identity alive". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Kaur, Usmeet (3 October 2016). "'Mini Peshawar' stands united for peace in Punjab". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Kahol, Vikas (16 August 2012). "Indian citizenship marred with struggle for Pak Hindus". India Today. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Kumar, Ruchi (1 January 2017). "The decline of Afghanistan's Hindu and Sikh communities". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

Historically, Hinduism thrived in Afghanistan, particularly in Pashtun areas.

- "Uncovering the roots of Bollywood stars in Peshawar". India Today. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Khan, Javed (18 January 2015). "Madhubala: From Peshawar with love ..." Dawn. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Arshad, Sameer (27 January 2017). "Once scorned, how Peshawaris became Bollywood kings". Times of India. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Singh, Mayank Pratap (6 September 2016). "Kader Khan to Amjad Khan, Bollywood legends who hail from Balochistan". India Today. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Yesvi, Affan (29 August 2016). "How Balochistan gave birth to the best of Bollywood". Daily O. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Mahmood, Rafay (1 January 2019). "Kader Khan: The Kakar from Balochistan who ruled Bollywood". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Khans in Bollywood: Afghan traces their Pathan roots". Deccan Herald. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Akbar Ahmed (27 February 2013). The Thistle and the Drone: How America's War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-8157-2379-0.

- Swarup, Shubhangi (27 January 2011). "'My Name is Mohammed Aamir Hussain Khan'". Open. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Anand, Dev (19 August 2004). "What If Prithviraj Kapoor Had Not Left Peshawar?". Outlook India. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Shelley Cobb; Neil Ewen (27 August 2015). First Comes Love: Power Couples, Celebrity Kinship and Cultural Politics. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-62892-120-5.

- Venkatesh, Karthik (6 July 2019). "The strange and little-known case of Hindko". Live Mint. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Taqi, Mohammad (11 December 2012). "A Legend By Any Definition". Outlook India. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

And perhaps Dilip Kumar does not know but in Peshawar his screen name is pronounced ‘Daleep’ with a thick Hindko accent.

- "Hindi cinema's iconic hero Dilip Kumar turns a year older". Times of India. 17 September 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Born into a Hindko-speaking Peshawari Pashtun family of 12 children, Dilip Kumar was born in Peshawar, now in Pakistan.

- "'The King of Tragedy': Dilip Kumar's 92nd birthday celebrated in the city". The Express Tribune. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Kumar was born as Yousuf Khan in the Hindko-speaking Awan family on December 11, 1922 in Mohallah Khudadad, near Qissa Khwani Bazaar, Peshawar.

- Khan, Omer Farooq (19 March 2010). "SRK's ancestral home traced to Pakistan". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

There is a strong misperception about Shah Rukh's identity who is widely considered as a Pathan. In fact, his entire family speaks Hindko language. His ancestors came from Kashmir and settled in Peshawar centuries back, revealed Maqsood.

- "Shahrukh's cousins eager to meet him". Dawn. 26 July 2005. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

Mr Ahmed said that the celebrity understood Hindko and loved to speak in his mother-tongue despite having been born away from Hindko speaking area.

- Rāj Gurovar (2018). The Legends of Bollywood. Jaico Publishing House. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-93-86867-99-5.

- Pradhan, Aneesh (5 July 2014). "Listen to the distinctive strains of old sarod masters before the gharanas mingled". Scroll. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

Gharanas of sarod players have their origins in the lineages of the Pathan communities that brought the Afghan rabab to India.

- Javeri, Lakshmi Govindrajan (16 February 2019). "Tuning into a legacy: Meet the sarod players Amaan Ali Bangash and Ayaan Ali Bangash". The Hindu. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Parvez, Amjad (17 July 2018). "GM Durrani — a runaway singer from Peshawar in the colonial era". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Ojha, Abhilasha (20 January 2003). "Play it again, Sami". Rediff. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Pelevin, Mikhail (16 April 2018). "Pashto Literature in North India in the 16th-18th Centuries". UCLA Program on Central Asia. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Rahman, Tariq (2001). "The Learning of Pashto in North India and Pakistan: An Historical Account". Journal of Asian History. 35 (2): 158–187. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Abubakar Siddique (2014). The Pashtun Question: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Hurst. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-84904-292-5.

- "Air World Service: Pashto". All India Radio. 2015. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "External Services Division". Prasar Bharati. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "External Services of AIR enters 80th year of its existence". News on Air. 1 October 2018. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Homepage". Centre of Persian and Central Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Pashto and Dari popular with Indian students at JNU". Business Standard. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Shankwar, Aranya (15 March 2018). "BA done, MA unsure, JNU's Pashto students ask: What next?". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Ghosh, Shrabona (24 December 2018). "Afghani students' plight continues, still no sign of Pashto in curriculum". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Khurshid, Salman (12 August 2018). "All the best, my fellow Pathan". The Week. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

We both belong to the Pathan (called Pashtuns in Afghanistan) tribes of the North-West Frontier who migrated to different parts of undivided India. His clan settled in what is now Pakistan and my clan of Afridi Pathans, including Pakistani cricketer Shahid Afridi’s ancestors, settled in Rohilkhand.

- Masood, Naved (19 June 2011). "Mohammed Yunus (1916-2001): The Migrant from Pakistan". Two Circles. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Peter Oborne (9 April 2015). Wounded Tiger: A History of Cricket in Pakistan. Simon and Schuster. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-84983-248-9.

- Ezekiel, Gulu (27 June 2017). "Afghan cricket: The Indian connection". Rediff. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Rajamani, R.C. (3 June 2011). "Bowled over by Durrani". The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Alavi, Shams Ur Rehman (11 December 2008). "Indian Pathans to broker peace in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

The three most famous Indian Pathans are Dilip Kumar, Shah Rukh Khan and Irfan Pathan.

- "World's oldest hockey Olympian Feroze dies". Dawn. 21 April 2005. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "World's oldest Olympian Feroze Khan passes away". Daily Times. 22 April 2005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2005. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Khan, Aslam Sher (1982). "To Hell With Hockey: My Father, My Role Model". Bharatiya Hockey. Allied Publishers. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

After the 1936 Olympics, Ahmed Sher Khan married a lissome Pathan lass called Ahmedi, who bore him two daughters and me.

- Rana, Ajay (22 July 2011). "When time stood still". The Sunday Indian. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

With only eight minutes to go, a barely known Pathan, Aslam Sher Khan, was sent in as a substitute for Michael Kindo.

- Hussain, Khalid (19 January 2020). "The first Emperor". The News. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

Bari was also a Pathan who had settled in Bombay. He was popular among CCI members, who raised money for him to go and compete in the 1950 British Open in London.

- Curiel, Jonathan (19 May 2000). "Seattle Sisters Won't Be Squashed / Feud with sport's establishment taking some of the fun out of it". Seattle Pi. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Yusuf Khan Takes Squash Open; Terrell Loses Consolation Match". Harvard Crimson. 16 November 1970. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Yusuf Khan Dies at 87". US Squash. 1 November 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Dicky Rutnagur (1997). Khans, Unlimited: A History of Squash in Pakistan. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-19-577805-2.

Yusuf Khan, professional at the Cricket Club of India in Bombay, was an Indian national when he migrated to America, but is a Pathan.

- "A Biblical Connection". Times of India. 11 March 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Ovais, Dar (2 April 2019). "For Afghan students, Chandigarh is their second home". The Indian Express. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Das, Bijoyeta (3 June 2013). "Afghan students flock to India's universities". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Pashto and Dari popular with Indian students at JNU". Zee News. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

"In India, Pashto is a developing language and it is rising very fast. For the mode of vacancy, we students are looking for a good designation and this language can give me a better designation in Central Government of India jobs," said Ambalika, a student who has completed advanced diploma in Pashto language. "Pashto language is a native language of Afghanistan and the importance of this language is immense in India. The students can get opportunities by learning Pashto language. The relation between India and Afghanistan is very historic and it will continue in the future. Learning the Afghan language is important to know more about India and Afghanistan relations," said Syed Ul Rehman, a student. The Pashto language programme is running successfully as more students are enrolling for this course.

- "Dated July 20, 1954: Pakhtoons in Kashmir". The Hindu. 20 July 2004. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Wani, Ieshan Bashir (24 July 2018). "In Kashmir, community of Pashtuns strives to protect its culture, identity". WION. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Karim Lala: The man who shaped Mumbai's underworld". Deccan Herald. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Singh, Sunil; Tiwari, Vaibhav (17 January 2020). "All About Karim Lala, The Name That Fueled Sena-Congress Spat". NDTV. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Who was Karim Lala?". Indian Express. 16 January 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Anna Bigelow (4 February 2010). Sharing the Sacred: Practicing Pluralism in Muslim North India. OUP USA. pp. 42, 43, 63, 93, 146, 199, 285. ISBN 978-0-19-536823-9.

- Bhardwaj, Ananya (30 August 2016). "Why Punjab's Malerkotla did not boil over after Quran desecration". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Taylor C. Sherman (25 August 2015). Muslim Belonging in Secular India: Negotiating Citizenship in Postcolonial Hyderabad. Cambridge University Press. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-1-316-36871-8.