Ormus

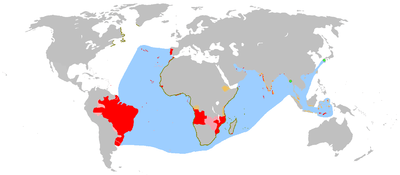

The Kingdom of Ormus (also known as Hormuz; Persian/Arabic: هرمز, Portuguese: Ormus) was located in the eastern side the Persian Gulf and extending as far as Bahrain in the west in its zenith . The Kingdom was established by an Omani prince in the 11th century initially as a dependency of the Kerman Seljuk Sultanate, and later as an autonomous tributary of the Salghurids and the Ilkhanate of Iran.[1] Ormus later became a client state of the Portuguese Empire, most of its territory was eventually annexed by the Safavid Empire in the 17th century.

.jpg)

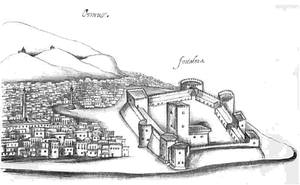

The Kingdom received its name from the fortified port city which served as its capital. It was one of the most important ports in the Middle East at the time as it controlled seaway trading routes through the Persian Gulf to China, India, and East Africa. This port was originally located on the southern coast of Iran to the east of the Strait of Hormuz, near the modern city of Minab, and was later relocated to the Island of Jarun which came to be known as Hormuz Island,[2] which is located near the modern city of Bandar-e Abbas.

Etymology

"Hormuz" is a derivation of Ahuramazda. The name of the actual urban settlement that acted as the capital of the Old Hormuz Kingdom was also given as Naband.[3]

Old Hormuz and New Hormuz

The original city of Hormuz was situated on the mainland in the province of Mogostan (Mughistan) of the province of Kirman, today's region of Minab in Hormozgan. At the time of the Ilkhanid competition with the Chaghataids, the old city of Hormuz, also known as Nabands and Dewankhana, was abandoned by its inhabitants. In stead, in 1301, the inhabitants, led by the king Baha ud-Din Ayaz and his wife Bibi Maryam, moved to the neighbouring island of Jerun.[4][5]

"It was during the reign of Mir Bahdin Ayaz Seyfin, fifteenth king of Hormuz, that Tartars, raided the kingdom of Kerman and from there to that of Hormuz. The wealth of Hormuz attracted raids so often that the inhabitants sought refuge off the mainland and initially moved to the island of Qeshm. Mir Bahdin then visited the island of Jerun and obtained it from Neyn (Na'im), King of Keys (Kish), to whom all the islands in the area belonged." [6]

Risso writes: "In the eleventh century, Saljûq Persia developed at the expense of what was left of Buwayhid Mesopotamia and the Saljûqs controlled ‘Umânî ports from about 1065 to 1140. Fâtimid Egypt attracted trade to the Red Sea route and away from the Persian Gulf. These shifts in power marked the end of the [Persian] Gulf's heyday, but the island ports of Qays and then the mainland port of Hormuz (at first tributary to Persia) became renowned entrepôts. The Hurmuzî rulers developed Qalhât on the ‘Umânî coast in order to control both sides of the entrance to the Persian Gulf. Later, in 1300, the Hurmuzî merchants cast off Persian overlordship. and reorganized their entrepôt on the island also called Hurmuz and there amassed legendary wealth. The relationship. between the Nabâhina and the Hurmuzîs is obscure". [7]

Abbé T G F Raynal gives the following account of Hormuz in his history: Hormúz became the capital of an empire which comprehended a considerable part of Arabia on one side, and Persia on the other. At the time of the arrival of the foreign merchants, it afforded a more splendid and agreeable scene than any city in the East. Persons from all parts of the globe exchanged their commodities and transacted their business with an air of politeness and attention, which are seldom seen in other places of trade. The streets were covered with mats and in some places with carpet, and the linen awnings which were suspended from the tops of the houses, prevented any inconvenience from the heat of the sun. India cabinets ornamented with gilded vases, or china filled with flowering shrubs or aromatic plants adorned their apartments. Camels laden with water were stationed in the public squares. Persian wines, perfumes, and all the delicacies of the table were furnished in great abundance, and they had the music of the East in its highest perfection … In short, universal opulence, an extensive commerce, politeness in the men and gallantry in the women, united all their attractions to make this city the seat of pleasure.[8]

History

There are three periods in the history of the Kingdom of Ormus: First, Mohammed Diramku migrated from Oman to the Iranian coast in the eleventh century. The capital was transferred to the island of Hormuz in the fourteenth century. In the second period, the island of Hormuz eclipsed the commercial power of the island of Kish. Hormuz become the greatest emporium in the Persian Gulf. The last period begin with the attack of the Portuguese of Alfonso of Albuquerque. [9]

The oldest references to the Kingdom of Hormuz is Shabankareyi's history of the kings of the region which runs to the middle of the 14th century. The original location of the kingdom's chief city was on the coastal parts of southern Iran, near the present city of Minab.[10].

The primary sources on the founding of the Kingdom of Hormuz always mention a dynasty of the ‘old kings of Hormuz’ which in fact come to an end with the 13th century rise of Mahmud Qalahati. The last king of the dynasty, Shihab ud-Dīn Muhammad b. ‘Isa, in fact becomes the genealogical ancestor of the later dynasty, but is presented in the sources as the end of his line, called the Deramkū Dynasty (Al Deramkū).

The founder of what Shabankareyi calls 'the line of the old kings of Hormuz' was Muhammad Deramku(h/b?), supposedly hailing from Oman, who arrived in Hormuz region, called Mughistan, at the end of the 11th or early 12th century.[11]. The origins of Deramku is obscure, although Shabankareyi tells us that the Deramku dynasty in fact had local origins.[12] Muhammad's move to Hormuz from Oman might have in fact been caused by the collapse of Buyid power in the south of Iran and the Persian Gulf and Sea of Oman region following the death of al-Malik al-Rahim in 1059.[13]. The Omani origin might simply be based on the later origin of Mahmud Qalahati who similarly hailed from the Oman region. Local histories, including Natanzi, mention that Muhammad Deramku’s connections were most closely with the Kerman region. In fact, the timing would make sense , as the rise of Dearmkū in Hormuz seems to parallel the rise of the local Seljuq Dynasty of Kerman, founded by Malikshah’s brother, Qavurd.

By controlling parts of Oman, Minab, and Mūghistān, Deramku managed to create a power base on the eastern side of the Straight of Hormuz and enter into direct competition with the rulers of Kish (Qais) who were previously vassals of the Buyids of Fārs. The connection between Hormuz and Kerman is also probably paralleling the connections between Kish and Shiraz (and further Isfahan), making Hormuz an important link in Kerman’s claims to supremacy in the trade of the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea.

We do not know much about Muhammad’s successors except their names. He appears to have been succeeded by his son Sulaimān and he was in turn succeeded by his son, ‘Isā Jāshū. The latter’s title of Jāshū “naval soldier”, might say something about the ruling society of Old Hormuz. Muhammad Deramku himself had managed to conquer Mūghestān and Mināb by the help of Omani Jashu soldiers, thus establishing the supremacy of naval officers and seamen in a kingdom that was essentially a thalassocracy, with most of its territory consisting of water.

‘Isā’s successor was called Lashkari. He appears to not have been an active ruler, stepping aside in favour of his son Kay Qubad. The latter’s successors were his two sons, one ‘Isa, who was known to be warlike, and the other, Mahmud. The branches of the family evidently fought each other as Tāj ud-Dīn Shahanshah son of Mahmud was also in conflict with an uncle, Malik Saif ud-Dīn Abu Nasr son of Kay Qobad. Shahanshah sought a closer relationship with Malik Dinār the Oghuz, the ruler of Kerman on behalf of the Khwarazmshahids. The latter, playing on the competition between Hormuz and Kish, used the situation to his advantage, extracting a high tribute from Shahhanshah. The unrest caused by this tipped the scale toward Abu Nasr, who initially accepted the overlordship of the ruler of Shabankara, Dīj, and later that of the great Salghurid Atabeg, Abu Bakhr b. Sa’ad.

Abu Nasr, an expansionist, used the patronage of the ruler of Fars in order to defeat his old enemies. As Vassaf tells us, he and his soldiers boarded a ship to Kish and on 8 May 1229, invaded that island, killing Malik Sultān, its ruler, and putting an end to the local dynasty of Banu Qaissar, the old rulers of the island and the major power in the Persian Gulf region. The patronage of Fārs soon came to an end, the relationship between Abu Nasr and Abu Bakhr quickly souring. Abu Bakr thus conquered Hormuz, killed Abānasr, and annexed Hormuz to Fārs, changing the name of the city of Hormuz (known as Nāband) to Dēwānkhāna.

Instead of AbU Nasr, to rule Hormuz, Abu Bakr installed Shihāb ud-Dīn Muhammad, son of Isa, son of Kay Qobad. The new ruler married his cousin Bībī Nāssir ud-Dīn , the daughter of Abu Nasr. The queen was much better cut as a ruler and political player than her husband. Perhaps recognizing the precarious position in which her father and uncles had put Hormuz, swinging between Kerman and Fars (and sometimes even Shabankara), Bibi Nāssir ud-Dīn proceeded to find a man who could help her regain the relative independence of Hormuz. The man was Abulmakārim Rukn ud-Dīn Mahmud Qalhati (Kalahaty/Kalahati).

The New Kings of Hormuz

Bībī Nāssir ud-Dīn and Mahmud soon managed to rid themselves of Shihab ud-Dīn Muhammad by poisoning him and in 1248, took advantage of the disarray at the court of the Salghurid Atabaks of Fars to slowly incorporate their rule. Sources talk about the expansion of the rule of Hormuz over parts of Oman and the port cities further east to northern India, as well as over Qallahat and Julfar. Mahmud and Bibi Naser ud-Din used the momentum caused by the disappearance of their Kerman and Fars overlords to project their power on both sides of the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman, controlling as far south as Dhofar and west as Bahrain and settling merchant communities on the coast of Makran and Sind, controlling the Indian trade routes. Their efforts essentially changed the focus of Hormuz away from its hinterland of southern Iran to one more focused on the southern coast of the Persian Gulf. The peace must have been unstable, as soon the onslaught the Mongols under Hulegu put an end to the Salghurid rule of Fars. In 1264, the last of the Salghurids was murdered, and a Mongol governor called Sughunjagh was appointed in his stead. The rising Mongol taxes and their disregard for mercantile equilibrium of the region eventually resulted in a rebellion in Hormuz, led by Rukn ud-Dīn Mahmud himself. The prolonged war resulted in Mahmud’s eventual departure to Kish, were the Mongol ruler could not reach him due to a lack of naval power, and eventually Qalhat, where he died in 1286.

The disarray caused by the Mongol rule in the region continued under the rule of Mahmud’s sons. His son Qutb ud-Dīn Tahmtan was soon killed and was succeeded by his brother Sayf ud-Dīn Nusrat who gained the throne with the help of the Qarakhitai ruler of Kerman, Suyurghatmish. At the time, the rule of Fars was in hands of Malik ul-Islam Jamal ud-Dīn Ibrahim Tibi, on behalf of the Ilkhanid ruler, Ghazan Khan. The overlord of the islands and the coastal regions was Ibrahim Tibi’s son, Malik al-Mu'azzam Fakhruddin Ahmad, under whose rule Sayf ud-Dīn Nusrat ruled. Nusrat seems to have been a blood-thirsty ruler who, in order to consolidate his rule, proceeded to murder all of his eight remaining brothers. However, two of his remaining brothers, Taj ud-Dīn Mas'ūd and Shams ud-Dīn Tūrkānshah who had taken refuge initially in Sirjan and later in the Mongol court, managed to overpower him and kill him in 1291.

Ayaz and New Hormuz

This murder caused a rebellion in Hormuz, led by one of the most important and influential characters in the history of Hormuz, Baha ud-Dīn Ayaz, aided by his able wife, Bibi Maryam. Ayaz, a former ghulam (slave) of Nusrat, managed to kick Mas’ud and Turkanshah out of Hormuz and exile them to Kerman. Taking over the throne of Hormuz himself, Ayaz quickly acknowledged the suzerainty of Malik al-Mu’azzam, the son of Ibrahim Tibi and the ruler of the Coast and the Islands. By 1296, however, the competition between the Ilkhanids and their cousins in Central Asia, the Ulus of Chaghatai, was expanding into the Iranian Plateau and the Fars region as well. Ayaz, by paying tribute to both side, kept Hormuz out of the conflict, but managed to take advantage of the situation by leaving the mainland.[14] Apparently as early as 1290’s, he had foreseen the attack on Iran and the south by the Chaghataids, and had thus started the construction of a new settlement on the island of Jarūn, opposite the site of Hormuz. When in 1301, the Chaghataid armies indeed attacked Fars and proceeded to the coast, Ayaz removed and resettled the population and possession of Hormuz in the new city, called New Hormuz, on the island of Jarūn, thus saving the lives and livelihood of the people of his prosperous land.[15] From this point on, the capital of the kingdom became the island city of Hormuz, the old Hormuz eventually becoming an abandoned site. Bibi Maryam, Ayaz's wife, became the ruler of Qalhat and is credited with much construction and prosperity in the region.[16]

The move to New Hormuz was the beginning of the rise of Hormuz as a commercial and political power. The island site, although lacking water, was strategically well located and naturally protected. It was located on important shipping lines and took advantage of good currents and a closeness to the mainland, making it a perfect emporium for the goods coming from India, as well as those from Iran. Later accounts talk about the prosperity of the island (slowly taking on the name of Hormuz, as it is today), its amazing bazaars, and the efficiency of its provisions, including government funded water cisterns that guaranteed people’s livelihoods. Much of this is credited to Ayaz and his liberal policy of offering protection to merchants and welcoming trade from all directions.[17]

The Restoration of the Deramku Dynasty

Ayaz ruled the new island and its possessions until 1311, when he retired to Qalhat, appointing a descendants of Shihab ud-Dīn Mahmud (the ‘last of the old kings of Hormuz’) to rule the new kingdom. The new king, Izz ud-Dīn Gurdānshah son of Salghur son of Shihab ud-Dīn Mahmud, was an able warrior and a generous ruler who continued Ayaz's policies. A dispute with the ruler of Kish, Shaikh Nu’aim, brought Gurdanshah to conflict with the ruler of the coast and the islands, the other son of Ibrahim Tibi, known as Izz ud-Dīn Abdul-Azīz. The Tibi ruler, with the support of Uljaitu Khan, claimed ancestral possession of Hormuz - now a prosperous island kingdom - and put a siege on Hormuz that was stifling its lucrative trade. A meeting inside a boat resulted in the capture of Gordan Shah and his imprisonment in Kish. Bibi Sultan, Gurdanshah’d wife, mounted a naval battle against Izz ud-Dīn Abdul Aziz. However, unfavourable conditions delayed the start of the battle, but allowed for Gurdanshah to escape from Kish and return to Hormuz, where he ruled until his death in 1317. The conflict with the Tibis was temporarily halted by the payment of tribute of '30,000 Hormuzi dirhams' to Abdul Aziz.[18] Gordan Shah was succeeded by his son Bahramshah, the latter soon being deposed and murdered by his brother-in-law (husband of Gurdanshah’s daughter Bibi Naz Malek), Shihab ud-Din Yusef. Two of Bahramshah’s brothers, Tahmtan and Kay Qobad, escaped to Kish and later to the Tibi court in Lār, asking for help from Rukn ad-Dīn Mahmud, the new ruler of Fars and a brother of Izz ud-Dīn Abdul Aziz. In 1318, with the help of the Tibi ruler, Tahmtan and Kay Qobad removed Yusef from the throne, installing Tahmtan as the new ruler.

Qutb ud-Dīn Tahmtan is one of the most energetic rulers of Hormuz. A great organizer, his rule is marked by the expansion of Hormuz’s commercial power, development of the island of Hormuz itself, and the transformation of Hormuz to the centre of an impressive empire spreading as far east as the coast of India and west as the region of Basra. He was also a brutal military leader. His initial ruler was faced with another claim by Ghiyath ud-Din, the son of Nu’aim of Kish, and an attack on Hormuz which was thwarted by Tahmtan’s generals, Muhammad Surkhab and Ibrahim Sulghur. Tahmtan’s revenge, upon returning to Hormuz from Mūghistan, was complete. The army of Hormuz conquered Kish, arrested all the dicendants of Nu’aim, including Ghiyath ud-Dīn, and massacred much of the resistance in Kish. The captured were moved to Hormuz and later killed, fully incorporating Kish into the kingdom of Hormuz.[19] Further conquests brought Kharg, Andarabi and other islands further west under Tahmtan’s control. By 740’s, Tahmtan was the undisputed ruler of all of the islands of the Persian Gulf and the lord of many of the coastal regions, including Mughestan, Gambrun, Rishahr, Zufar, Qallahat, and Oman.

This prosperity was helped by the confused state of affairs in Fars and Kerman, where the post—Ilkhanid successor states like the Jalayerids and smaller dependencies like the Injuids and Muzafarids were less concerned with the affairs of the coastal regions and the islands. This allowed for Tahmtan to consolidate his power and establish Hormuz as the centre of his commercial sea-empire. The population of Hormuz at this time consisted of Sunni and Shi’a Muslims, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, as well as Hindus and Buddhists. The island was known for its luxuries, emporia, and mixed population and languages. This is when the famous traveler Ibn Battuta visited Hormuz and wrote about its prosperity and the cultural patronage of its ruler, Qutb ud-Dīn Tahmtan. Hormuz during this time was a sea-empire with islands at its centre and coastal regions of the Iranian Plateau and the Arabian peninsula as its peripheries, keeping it away from the troublesome politics of the interior regions.

The long rule of Tahmtan toward the end was interrupted by a coup under his loyal brother, Kay Qobad, who took advantage of Tahmtan’s visit to the coastal port of Gambrūn (later Bandar-e Abbas), declared himself king. Tahmtan did not try to resist, retiring to Qalhat, waiting until Kay Qubad’s death a year later. Upon returning to the throne, Tahmtan tried to buy the friendship of Kay Qubad’s sons, Shanba and Shadi, who refused. The pursuing war ended in Tahmtan’s success. However, he was soon dead, in 1346, being succeeded by his son Yusef, known as Turan Shah I. Turan Shah continued the tolerant policies of his father and grand-father, giving priority to the security of the port of Hormuz and to the passage of goods through the Strait of Hormuz by strengthening his hold over the region of Qalhat (modern region of Musandam). The trade of Hormuz at this time consisted of goods coming from India and Southeast Asia, usually destined for the markets of Iran and Iraq, as well as goods, including slaves, coming from Central Asia.[20] A contemporary of Tahhmtan describes the situation as such:

- "After having secured his country on land and sea and among Arabs and non-Arabs against his opponents, Sultan Qutb al-Din formed good relations with the sultan of sultans of

- Gujarat, lands of the kings (muluks) of India, Sind, Basra, Kufa, Oman, Kirman, Shiraz and so on until he stabilized his rule and dominance and spread his justice. He prepared : ships and sent them everywhere. From all seaports such as Mecca, Jidda, Aden, Sofala, Yemen, China, Europe, Calicut, and Bengal they came by sea and brought superior merchandise from everywhere to there and they brought valuable goods from the cities of Fars, Iraq and Khurasan to that place. From whatever that came by sea they took one tenth, and from whatever was brought to Khurasan from [surrounding areas], they took half of one tenth, and it has remained the same way and order until now and in this year (747/1346) after ruling honorably for twenty-two years, his soul ascended to holy land."[21]

The rule of Turan Shah I and his son Bahman Shah was contemporary with the competition between the post-Ilkhanid competition between the Jalayerids and local powers of Fars, including the Injuids and Muzaffarids. Attempts by Muhammad Muzaffar to control Hormuz were rendered unsuccessful by Turan Shah who essentially paid the Muzaffarid ruler off in ordet to keep the independence of Hormuz intact.[22] The kings of Hormuz, continuing to pay their tribute to the local rulers of Fars and Kerman, managed to keep themselves away from such conflicts, continuing to preserve their commercial supremacy. Control of islands like Bahrain also provided the kingdom with export items like pearls, providing an additional means of income to the rulers. A later observer, Gaspar da Cruz, describes Hormuz as such:

- "Hormuz . . . is, among all the wealthy countries of India, one of the wealthiest, through the many and rich goods that come thither from all parts of India, and from the whole of Arabia and of Persia, as far as the territories of the [Mongols], and even from Russia in Europe I saw merchants there, and from Venice. And thus the inhabitants of Ormuz say that the whole world is a ring and Hormuz is the stone thereof."[23]

Muhammad Shah I, the son of Bahman Shah, was a contemporary of the later Timurids. In the struggle between Umar Shaikh and Jahangir, Hormuz' possession on the mainland, particularly the area of Mughistan, the resort of the wealthy Hormuzis, were threatened. Muhammad Shah managed to fend off the Timurid princes, although Mughistan was attacked by Jahangir at least once.

Bahman Shah II and Turan Shah II presided over a prosperous period when the kings of Hormuz became patrons of learning and knowledge. As Sunni kings, they were very tolerant of Shi'as, Nestorian Christians, Jews, Hindus, and even "pagans" (most likely Hindus).[24] They built several schools in which scholars like Safi ad-Din Iji resided and taught, [25] and Turan Shah II himself appears to have been an accomplished poet. In fact, his lost composition, Shahnameh-e Turn Shahi, was the main source for the history of Hormuz. Its translation by later Portuguese travelers and scholars such as Pedro Teixeira in fact are all we know of the early history of Hormuz, including its Old Kings.[26]

The four sons of Turan Shah II got into a rivalry over the succession to their father, with Shahweis Shengelshah initially coming out as the successful one. However, his brother Salghur Shah managed to remove his brother and deprive his sons of the throne, ruling himself until 1504. His rule was perhaps the last period of prosperity for Hormuz before the arrival of the Portuguese. Salghur Shah's two sons, including Turan Shah III, ruled less than a year, before being removed by their cousin, Sayf ud-Din Abu Nasr Shah.

It was during the reign of Abu Nasr Shah that the Portuguese Conquest of Hormuz took place, first in 1507 and then completed in 1515 by Alfonso de Albuquerque. The second conquest resulted in establishment of a Portuguese fortress on the island and the take over the customs house by the Portuguese, leading to a prolonged decline of the commercial empire of Hormuz.

.jpg)

Portuguese conquest

In September 1507, the Portuguese Afonso de Albuquerque landed on the island. Portugal occupied Ormuz from 1515 to 1622.

It was during the Portuguese occupation of the island that the Mandaeans first came to western attention. The Mandaeans were fleeing persecution in the vilayet of Baghdad (which, at the time, included Basra) and Khuzestan in Iran. When the Portuguese first encountered them, they mistakenly identified them as "St. John Christians", analogous to the St. Thomas Christians of India. The Mandaeans, for their part, were all too willing to take advantage of the confusion, offering to accept papal authority and Portuguese suzerainty if the Portuguese would invade the Ottoman Empire and liberate their coreligionists. The Portuguese were attracted by the prospect of what appeared to be a large Christian community under Muslim rule. It was not until after the Portuguese had committed themselves to the conquest of Basra that they came to realize that the Mandaeans were not what they claimed to be.

As vassals of the Portuguese state, the Kingdom of Ormus jointly participated in the 1521 invasion of Bahrain that ended Jabrid rule of the Persian Gulf archipelago. The Jabrid ruler was nominally a vassal of Ormus, but the Jabrid King, Muqrin ibn Zamil had refused to pay the tribute Ormus demanded, prompting the invasion under the command of the Portuguese conqueror, António Correia.[27] In the fighting for Bahrain, most of the combat was carried out by Portuguese troops, while the Ormusi admiral, Reis Xarafo, looked on.[28] The Portuguese ruled Bahrain through a series of Ormusi governors. However, the Sunni Ormusi were not popular with Bahrain's Shia population which suffered religious disadvantages,[29] prompting rebellion. In one case, the Ormusi governor was crucified by rebels,[30] and Portuguese rule came to an end in 1602 after the Ormusi governor, who was a relative of the Ormusi king,[31] started executing members of Bahrain's leading families.[32]

The kings of Hormuz under the Portuguese rule were reduced to vassals of the Portuguese empire in India, mostly controlled from Goa. The archive of correspondence between the kings and local rulers of Hormuz,[33] and some of its governors and people, and the kings of Portugal, contain the details of the kingdom's disintegration and the independence of its various parts. They show the attempts by rulers such as Kamal ud-Din Rashed trying to gain separate favour with the Portuguese in order to guarantee their own power.[34]. This reflects in the gradual independence of Muscat, previously a dependency of Hormuz, and its rise one of the successor states to Hormuz.

After the Portuguese made several abortive attempts to seize control of Basra, the Safavid ruler Abbas I of Persia conquered the kingdom with the help of the English, and expelled the Portuguese from the rest of the Persian Gulf, with the exception of Muscat. The Portuguese returned to the Persian Gulf in the following year as allies of Afrasiyab, the Pasha of Basra, against the Persians. Afrasiyab was formerly an Ottoman vassal but had been effectively independent since 1612. They never returned to Ormus.

In the mid-17th century it was captured by the Imam of Muscat, but was subsequently recaptured by Persians. Today, it is part of the Iranian province of Hormozgan.

Accounts of Ormus society

Situated between the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, Ormus was a "by-word for wealth and luxury",[35] perhaps best captured in the Arab saying: "If all the world were a golden ring, Ormus would be the jewel in it".[35] The city was also known for its licentiousness according to accounts by Portuguese visitors; Duarte Barbosa, one of the first Portuguese to travel to Ormuz in the early 16th century found:

The merchants of this isle and city are Persians and Arabs. The Persians [speak Arabic and another language which they call Psa[36]], are tall and well-looking, and a fine and up-standing folk, both men and women; they are stout and comfortable. They hold the creed of Mafamede in great honour. They indulge themselves greatly, so much so that they keep among them youths for the purpose of abominable wickedness. They are musicians, and have instruments of diverse kinds. The Arabs are blacker and swarthier than they.[37]

This theme is also strong in Henry James Coleridge's account of Ormus in his life of the Navarrese missionary, St Francis Xavier, who visited Ormus on his way to Japan:

Its moral state was enormously and infamously bad. It was the home of the foulest sensuality, and of all the most corrupted forms of every religion in the East. The Christians were as bad as the rest in the extreme license of their lives. There were few priests, but they were a disgrace to their name. The Arabs and the Persians had introduced and made common the most detestable forms of vice. Ormuz was said to be a Babel for its confusion of tongues, and for its moral abominations to match the cities of the Plain. A lawful marriage was a rare exception. Foreigners, soldiers and merchants, threw off all restraint in the indulgence of their passions ... Avarice was made a science: it was studied and practiced, not for gain, but for its own sake, and for the pleasure of cheating. Evil had become good, and it was thought good trade to break promises and think nothing of engagements ...[38]

Depiction in literature

Ormus is mentioned in a passage from John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost (Book II, lines 1–5) where Satan's throne "Outshone the wealth of Ormus and of Ind", which Douglas Brooks states is Milton linking Ormus to the "sublime but perverse orient".[39] It is also mentioned in Andrew Marvell's poem 'Bermudas', where pomegranates are described as "jewels more rich than Ormus." In Hart Crane's sonnet To Emily Dickinson, it appears in the couplet: "Some reconcilement of remotest mind– / Leaves Ormus rubyless, and Ophir chill." The closet drama Alaham by Fulke Greville is set in Ormus.

List of kings of Hormuz

Old Kings (Muluk al-Qadim) (Dependency of Kerman until c. 1247)

- Muhammed I Deramku (محمد درمکو), About 1060

- Sulaiman b. Muhammad

- Isa Jashu b. Sulaiman (d. 1150)

- Lashkari b. Isa (d. 1189)

- Kay Qobad b. Lashkari

- Isa b. Kay Qobad

- Mahmud b. Kay Qobad

- Shahanshah b. Mahmud (d. 1202)

- Abu Nasr b. Kay Qobad (conquest of Hormuz by Atabeg of Fars, Abu Bakr)

- Mir Shihab ud-Dina Mahmud (Malang) b. Isa (d. 1247)

- (jointly with his wife, Bibi Nasir ad-Din bt. Abu Nasr)

New Kings (Muluk Jadid)

- Rokn ed-Din Mahmud Kalhati (1242–1277)

- (jointly with his wife, Bibi Nasir ad-Din bt. Abu Nasr)

- Qutb ud-Din Tahmtan I b. Mahmud Kalahati (under Bibi Nasir ad-Din's regency)

- Seyf ed-Din Nusrat b. Mahmud (1277–1290)

- Taj ud-Din Mas'ud b. Mahmud (1290–1293)

- Mir Baha ud-din Ayaz Seyfi (with his wife, Bibi Maryam; 1293–1311; moved the capital to Jarun)[40]

- Izz ud-Din Gordan Shah (son of Salghur son of Mahmud Malang; restoration of the old dynasty) (عزالدین گردان شاه) (1317–1311)

- Shihab ud-Din Yusef (husband of Naz Malek, d. of Gordan Shah) (1317-1319)

- Bahramshah (1319)

- Qutb al-Din Tahmtan II b. Gordan Shah (قطب الدین تهمتن) (1345–1319)

- Nizam ud-Din Kay Qubad b. Gordan Shah (usurpation, 1345-1346)

- Turan Shah I (Yusef) b. Tahmtan (1346-1377)

- Bahman Shah b. Turan Shah (1377-1389)

- Muhammad Shah I b. Bahman Shah (1389-1400)

- Bahman Shah II b. Muhammad Shah

- Fakhruddin Turan Shah II b. Firuz Shah b. Muhammad Shah

- Shahweis Shengel Shah b. Turan Shah

- Salghur Shah b. Turan Shah

- Turan Shah II b. Salghur Shah

- Sayf ud-Din Aba Nasr Shah b. Shengel Shah (at the time of Portuguese invasion; 1507-1513)

- Turan Shah IV b. Shengel Shah (1513-1521; Albuquerque's conquest of Hormuz in 1515)

- Muhammad Shah II b. Turan Shah (1521-1534)

- Salghur Shah II b. Turan Shah (1534-1543)

- Fakhr ud- Din Turan Shah V b. Salghur Shah II (1543-1565)

- Muhammad Shah III b. Firuz Shah b. Turan Shah V (1565)

- Farrukh Shah I b. Muhammad Shah (1565-1597)

- Turan Shah VI b. Farrukh Shah (1597)

- Farrukh Shah II b. Turan Shah VI (1597-1602)

- Firuz Shah b. Farrukh Shah II (1602-1609)

- Muhammad Shah IV b. Firuz Shah (1609-1622; conquest of Hormuz by Imam Quli Khan of Fars on behalf of Shah Abbas I)

See also

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Hormuz Island

- Monatomic Gold ORMUS

References

- Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p.122

- Shabankareyi, Muhammad. Majma al-Ansab. p. 215.

- Shabankareyi, Muhammad b. Ali (1363). Majma al-Ansab. Tehran: Amir Kabir. p. 215.

- Vosoughi, M. B. The Kings of Hormuz. p. 92.

-

- 127 The Travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd; E.P. Dutton & Co, London and Toronto; New York, 1926 ~ p. 63. Although Marco Polo refers to the island on which was the city of Hormuz, Collis states that at that time Hormuz was on the mainland. #85 Collis, Maurice. Marco Polo. London, Faber and Faber Limited, 1959~ p. 24.

- http://www.dataxinfo.com/hormuz/essays/3.3.htm

- Risso, Patricia, Oman And Muscat: an Early Modern History, Croom Helm, London, 1986 ~ p. 10.

-

- 252 Stiffe, A. W., The Island of Hormuz (Ormuz), Geographical Magazine, London, 1874 (Apr.), vol. 1 pp. 12–17 ~ p. 14

- The Persian Gulf in History L. Potter:https://books.google.com.pe/books?id=ncfIAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92&dq=Mahmud+Qalhati&source=bl&ots=Q6LSY6OG4G&sig=NXISgVl_rR9C07vxPXpfvwG2x-0&hl=es-419&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjgt7LphMrTAhWCYiYKHVDaACgQ6AEIJTAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Mirahmadi, Maryam (1369). "Jazireye Hormuz dar Motun Joghrafiyayi o Tarikhi-ye Qadeem". Tahqiqat-e Joghrafiyayi. 17: 101-123.

- Mohammad Bagher Vosoughi (2009). Potter, Lawrence G. (ed.). The Persian Gulf in History. Palgrame McMillan. p. 91.

- Shabankareyi. Majma al-Ansab. p. 215.

- Vosoughi, Mohammad Bagher (1380). "Iranian o Tejarat-e Daryayi-ye Khalij-e Fars dar Qorun-e Avvaliye-ye Eslami". Name-ye Anjoman. 4 (1): 192-193.

- Vosoughi, M. B. The Kings of Hormuz. p. 92.

- Shabankareyi, M. Majma al-Ansab. p. 216-217.

- Shabankareyi, M. Majma al-Ansab. p. 217.

- Natanzi, Mo'in ud-Din. Montakhab al-Tavarikh. p. 19.

- Shabankareyi, M. Majma al-Ansab. p. 217.

- Shabankareyi, Muhammad. Majma al-Ansab. p. 218-219.

- Vosoughi, M. B. The Kings of Hormuz. p. 94-98.

- Nimdehi, Qadi Abdul Aziz. Tabaqat-e Mahmudi. MS. p. (quoted in Vosoughi 2009: 93).

- Natanzi, Mo'in ud-Din. Mokhtasar al-Tavarikh. p. 21-22.

- Quoted in: Vosoughi, M. B. (2009). Kings of Hormuz. p. 97.

- Vosoughi, M. B. (2009). The Kings of Hormuz. p. 93-94.

- Vosoughi, M. B. (2009). The Kings of Hormuz. p. 96.

- Teixeira, Pedro (1902). The travels of Pedro Teixeira : with his "Kings of Harmuz" and extracts from his "Kings of Persia". London: Hokluyt Society.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, 1997, 288

- James Silk Buckingham Travels in Assyria, Media, and Persia, Oxford University Press, 1829, p459

- Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 pp39

- Charles Belgrave, Personal Column, Hutchinson, 1960 p98

- Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p6

- Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984 p69

- Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki dar Arshiv-e Melli-e Porteghal". Asnad.

- Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki..." Asnad.

- Peter Padfield, Tide of Empires: Decisive Naval Campaigns in the Rise of the West, Routledge 1979 p65

- pesh, a Semitic root for 'mouth', often connotes speech.

- The Book of Duarte Barbosa: An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and their inhabitants, written by Duarte Barbosa and completed about the year 1518 AD, 1812 translation by the Royal Academy of Sciences Lisbon, Asian Educational Services 2005

- Francis Xavier, Henry James Coleridge, The Life and Letters of St. Francis Xavier 1506–1556, Asian Educational Services 1997 Edition p 104–105

- Brooks, Douglas. Milton and the Jews. Cambridge University Press. pp. 188–. ISBN 9781139471183. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- https://archive.org/stream/sermarcopolonote00corduoft/sermarcopolonote00corduoft_djvu.txt

Bibliography

- Aubin, Jean. “Les Princes d’Ormuz du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Journal asiatique, vol. CCXLI, 1953, pp. 77–137.

- Natanzi, Mo'in ad-Din. Montakhab ut-Tawarikh-e Mo'ini. ed. Parvin Estakhri. Tehran: Asateer, 1383 (2004).

- Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki dar Arshiv-e Melli-ye Porteghal Darbarey-e Hormuz o Khaleej-e Fars." Barrasihaa-ye Tarikhi (1356-1357).

- Shabankareyi, Muhammad b Ali. Majma al-Ansab. ed. Mir-Hashem Mohadess. Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1363 (1984).

- Vosoughi, Mohammad Bagher. "the Kings of Hormuz: from the Beginning until the Arrival of the Portuguese." in Lawrence G. Potter (ed.) The Persian Gulf in History, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009.