Imadaddin Nasimi

Alī Imādud-Dīn Nasīmī (Azerbaijani: Seyid Əli İmadəddin Nəsimi سئید علی عمادالدّین نسیمی, Persian: عمادالدین نسیمی), often known as Nesimi, (1369 – 1417 skinned alive in Aleppo) was a 14th-century Azerbaijani[1][2] or Turkmen[3][4][5] Ḥurūfī poet. Known mostly by his pen name (or takhallus) of Nesîmî, he composed one divan in Azerbaijani,[6][7] one in Persian,[2][8] and a number of poems in Arabic.[9] He is considered one of the greatest Turkic mystical poets of the late 14th and early 15th centuries[9] and one of the most prominent early divan masters in Turkic literary history (the language used in this divan is the same with Azerbaijani).[9]

Imadaddin Nasimi | |

|---|---|

عمادالدین نسیمی İmadəddin Nəsimi | |

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1369 CE (approximate) |

| Died | 1417 CE |

| Cause of death | Death penalty, skinned alive |

| Religion | Islam, Alevi |

| Parents |

|

| Ethnicity | Azerbaijani/Turkmen |

| Era | Timurid |

| Known for | Azerbaijani epic poetry, wisdom literature, hurufi |

| Senior posting | |

| Period in office | 14-15th century |

Influenced by

| |

Influenced

| |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

List of sufis |

|

|

Life

Very little is known for certain about Nesîmî's life, including his real name. Most sources indicate that his name was İmâdüddîn,[10][11] but it is also claimed that his name may have been Alî or Ömer.[12] It is also possible that he was descended from Muhammad, since he has sometimes been accorded the title of sayyid that is reserved for people claimed to be in Muhammad's line of descent.

Nesîmî's birthplace, like his real name, is wrapped in mystery: some claim that he was born in a province called Nesîm — hence the pen name — located either near Aleppo in modern-day Syria,[10] or near Baghdad in modern-day Iraq,[11] but no such province has been found to exist. There are also claims that he was born in Shamakhi- which is mostly likely because his brother is buried in Shamakhi, Azerbaijan.

According to the Encyclopædia of Islam,[8]

an early Ottoman poet and mystic, believed to have come from Nesīm near Baghdād, whence his name. As a place of this name no longer exists, it is not certain whether the laqab (Pen-Name) should not be derived simply from nasīm zephyr, breath of wind. That Nesīmī was of Turkoman origin seems to be fairly certain, although the Seyyid before his name also points to Arab blood. Turkic was as familiar to him as Persian, for he wrote in both languages. Arabic poems are also ascribed to him.

From his poetry, it's evident that Nesîmî was an adherent of the Ḥurūfī movement, which was founded by Nesîmî's teacher Fażlullāh Astarābādī of Astarābād, who was condemned for heresy and executed in Alinja near Nakhchivan (Azerbaijan).[13] The center of Fażlullāh's influence was Baku (Azerbaijan) and most of his followers came from Shirvan (Azerbaijan).[14]

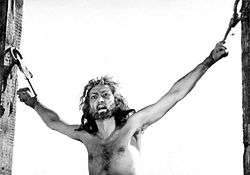

Nesîmî become one of the most influential advocates of the Ḥurūfī doctrine and the movement's ideas were spread to a large extent through his poetry. While Fażlullāh believed that he himself was the manifestation of God, for Nesîmî, at the center of Creation there was God, who bestowed His Light on man. Through sacrifice and self perfection, man can become one with God.[15] Around 1417, (or possibly 1404)[10][12] as a direct result of his beliefs — which were considered blasphemous by contemporary religious authorities — Nesîmî was seized and, according to most accounts,[10][12] skinned alive in Aleppo.

A number of legends later grew up around Nesimi's execution, such as the story that he mocked his executioners with improvised verse and, after the execution, draped his flayed skin around his shoulders and departed.[10] A rare historical account of the event — the Tarih-i Heleb of Akhmad ibn Ibrahim al-Halabi — relates that the court, which was of the Maliki school of religious law, was unwilling to convict Nesîmî of apostasy, and that the order of execution instead came from the secular power of the emir of Aleppo, who was hoping to avoid open rebellion.[16]

Nesîmî's tomb in Aleppo remains an important place of pilgrimage to this day.

Poetry

Nesîmî's collected poems, or dîvân, number about 300, and include ghazals, qasidas ("lyrics"), and rubâ'îs ("quatrains") in Azerbaijani Turkic,[17][2][18] Persian, and Arabic. His Turkic divan, considered his most important work,[9] contains 250–300 ghazals and more than 150 rubâ'îs. A large body of Bektashi and Alevi poetry is also attributed to Nesîmî, largely as a result of Hurûfî ideas' influence upon those two groups. Shah Ismail I, the founder of the Safavid dynasty in Iran, who himself composed a divan in Azerbaijani Turkic under the pen name of Khatai,[19] praised Nesimi in his poems.[20]

According to the Encyclopedia of Islam:[8]

His work consists of two collections of poems, one of which, the rarer, is in Persian and the other in Turkic. The Turkic Dīwān consists of 250-300 ghazels and about 150 quatrains, but the existing mss. differ considerably from the printed edition (Istanbul 1298/1881). No scholarly edition has so far been undertaken, but a study of his vocabulary is given by Jahangir Gahramanov, Nasimi divanynyn leksikasy, Baku 1970. The Persian Dīwān has been edited by Muhammad Rizā Mar'ashī, Khurshid-i Darband . Dīwān-i Imād Dīn Nasīmī, Tehran 1370 Sh./1991.

One of Nesîmî's most famous poems is the gazel beginning with the following lines:

- منده صغار ايكى جهان من بو جهانه صغمازام

- گوهر لامکان منم كون و مکانه صغمازام

- Məndə sığar iki cahan, mən bu cahâna sığmazam

- Gövhər-i lâ-məkân mənəm, kövn ü məkâna sığmazam[21]

- Both worlds can fit within me, but in this world I cannot fit

- I am the placeless essence, but into existence I cannot fit

- Both worlds fit into me I do not fit into both worlds (This world and the hereafter)

- I am a placeless gem (essence) I don’t fit into the place

- Throne and terrain, B and E all was understood in me (God said “be” and the universe was began)

- End your words be silent I don’t fit into Descriptions and Expressions

- The universe is my sine; the starting point of me goes to the essence

- You know with this sign, that I don’t fit into the sign

- With suspicion and impression, no one can grasp the truth

- The one who knows the truth knows that I do not fit into suspicion and impression

- Look at the form and the concept, Know inside the form that

- I’m composed of body and soul but I don’t fit into body and soul

The poem is an example of Nesîmî's poetic brand of Hurufism in its mystical form. There is a contrast made between the physical and the spiritual worlds, which are seen to be ultimately united in the human being. As such, the human being is seen to partake of the same spiritual essence as God: the phrase lâ-mekân (لامکان), or "the placeless", in the second line is a Sufi term used for God.[22] The same term, however, can be taken literally as meaning "without a place", and so Nesîmî is also using the term to refer to human physicality.[23] In his poem, Nesîmî stresses that understanding God is ultimately not possible in this world, though it is nonetheless the duty of human beings to strive for such an understanding. Moreover, as the poem's constant play with the ideas of the physical and the spiritual underlines, Nesîmî calls for this search for understanding to be carried out by people within their own selves. This couplet has been described in different pictures, movies, poems, and other pieces of arts.[24]

Some of Nesîmî's work is also more specifically Hurûfî in nature, as can be seen in the following quatrain from a long poem:

- اوزكى مندن نهان ايتمك ديلرسه ڭ ايتمه غل

- گوزلرم ياشڭ روان ايتمك ديلرسه ڭ ايتمه غل

- برك نسرین اوزره مسکين زلفكى سن طاغدوب

- عاشقى بى خانمان ايتمك ديلرسه ڭ ايتمه غل

- Gördüm ol ayı vü bayram eyledim

- Şol meye bu gözleri câm eyledim

- Hecce vardım ezm-i ehrâm eyledim

- Fâ vü zâd-ı lâm-i Heqq nâm eyledim[21]

- Seeing that moon I rejoiced

- I made of my eyes a cup for its wine

- I went on Hajj in pilgrim's garb

- I called Fâ, Zâd, and Lâm by the name "Truth"

In the quatrain's last line, "Fâ", "Zâd", and "Lâm" are the names of the Arabic letters that together spell out the first name of the founder of Hurufism, Fazl-ullah. As such, Nesîmî is praising his shaykh, or spiritual teacher, and in fact comparing him to God, who is also given the name "Truth" (al-Haqq). Moreover, using the Perso-Arabic letters in the poem in such a manner is a direct manifestation of Hurûfî beliefs insofar as the group expounds a vast and complex letter symbolism in which each letter represents an aspect of the human character, and all the letters together can be seen to represent God.

Nesîmî is also considered a superb love poet, and his poems express the idea of love on both the personal and the spiritual plane. Many of his gazels, for instance, have a high level of emotiveness, as well as expressing a great mastery of language:

- اوزكى مندن نهان ايتمك ديلرسه ڭ ايتمه غل

- گوزلرم ياشڭ روان ايتمك ديلرسه ڭ ايتمه غل

- برك نسرین اوزره مسکين زلفكى سن طاغدوب

- عاشقى بى خانمان ايتمك ديلرسه ڭ ايتمه غل

- Üzünü menden nihân etmek dilersen, etmegil

- Gözlerim yaşın revân etmek dilersen, etmegil

- Berq-i nesrin üzre miskin zülfünü sen dağıdıb

- Âşiqi bîxânimân etmek dilersen, etmegil[21]

- Should you want to veil your face from me, oh please do not!

- Should you want to make my tears flow, oh please do not!

- Should you want to lay your hair of musk atop the rose

- And leave your lover destitute, oh please do not!

Legacy

Nesîmî's work represents an important stage in the development of poetry not only in the Azerbaijani language vernacular, but also in the Ottoman Divan poetry tradition. After his death, Nesîmî's work continued to influence many Turkic language poets and authors such as Fuzûlî (1483?–1556), Khata'i (1487–1524), and Pir Sultan Abdal (1480–1550).

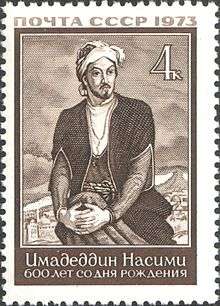

Nesîmî is venerated in the modern Republic of Azerbaijan, and one of the districts of the capital city, Baku, bears his name. There is also a monument to him in the city, sculpted by T. Mamedov and I. Zeynalov in 1979.[25] Furthermore, the Institute of Linguistics at the Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan is named after him, and there was also a 1973 Azerbaijani film, Nasimi (the Azerbaijani language spelling of his name), made about him. The 600th anniversary of Nesîmî's birthday was celebrated worldwide in 1973 by the decision of UNESCO, and representatives from many countries took part in the celebrations held both in Azerbaijan and in Moscow, Russia. An event dedicated to the 600th anniversary of Nasimi's death was conducted in Paris, at the headquarter of UNESCO in May 2017.[26][27][28] President Ilham Aliyev declared 2019 the "Year of Nasimi" in Azerbaijan as it was the 650th anniversary of the birth of the poet.[29][30][31] The year was also declared "the Year of the Azerbaijani Poet Imadeddin Nesimi" by the International Organization of Turkic Culture at the 36th Term Meeting of its Permanent Council in December 2018.[32]

Memory

- Asteroid 32939 Nasimi was named in his memory.[33] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 18 May 2019 (M.P.C. 114954).[34]

- The movie dedicated to the poet Nesimi by Azerbaijanfilm studio.

- The ballet dedicated to the poet A Tale of Nesimi by Azerbaijani composer Fikret Amirov in 1973.[35]

Various places are named in honor of Nasimi:

- The Nasimi Institute of Linguistics is part of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences.

- Nəsimi raion is an urban district (raion) in Baku.

- A Baku metro station is named Nəsimi.

.jpg) Nasimi park in Sumgait

Nasimi park in Sumgait - The urban middle school No 2 in Balaken, Azerbaijan is named for Nasimi [36]

- There are Nəsimi streets in Agdjabedi, Khudat and Baku.

- There are villages named Nasimi in Bilasuvar and in Sabirabad regions, as well as Nəsimikənd in the Saatly region of Azerbaijan.

- The seaside park in Sumgait was named after Nasimi in 1978 and a statue of him was erected there in 2003.[37]

"Nasimi Festival of Poetry, Arts, and Spirituality" was organized in September 2018 by the Heydar Aliyev Foundation and Ministry of Culture of Azerbaijan. The events featured different types of art and knowledge fields in Baku and the poet's home city Shamakhi.[38][39][40][41] In November 2018, the bust of Imadeddin Nasimi at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations was unveiled as a part of the Nasimi Festival.[42] From September 28 to October 1, the Second Nasimi Festival of Poetry, Art and Spirituality was held in Azerbaijan in the framework of the "Year of Nasimi".[43]

The "Nasimi-650" Second Summer Camp of Diaspora Youth of Azerbaijan was organized in Shamakhi dedicated to the poet’s 650th anniversary in July 2019.[44]

Songs to Nasimi's poems

- "İstəmə" – composer: Tofig Guliyev[45]

- "Qafil oyan" – composer: Tofig Guliyev[45]

- "Neynədi" – performed by Zeynab Khanlarova

- "Nasimi" – performed by Sami Yusuf[46]

See also

- Alevism

- Isma'ili

- Sufism

- Nāīmee

- Hurufiyya

- Nuktawiyya

- Murād Mīrzā

- List of Ismaili imams

- List of extinct Shia sects

References

- Encyclopaedia Iranica. Azeri Turkish

The oldest poet of the Azeri literature known so far (and indubitably of Azeri, not of East Anatolian of Khorasani, origin) is ʿEmād-al-dīn Nasīmī (about 1369-1404, q.v.).

- Burrill, Kathleen R.F. (1972). The Quatrains of Nesimi Fourteenth-Century Turkic Hurufi. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. ISBN 90-279-2328-0.

- Jo-Ann Gross, Muslims in Central Asia: expressions of identity and change, (Duke University Press, 1992), 172.

Andalib also wrote several mathnavis, the most famous of which is about the life of the fourteenth-century Iraqi Turkmen mystic Nesimi.

- The Celestial Sphere, the Wheel of Fortune, and Fate in the Gazels of Naili and Baki, Walter Feldman, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (May, 1996), 197.

- Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, Mehmet Kalpaklı, Ottoman lyric poetry: An Anthology, (University of Washington Press, 2006), 211.

- Průšek, Jaroslav (1974). Dictionary of Oriental Literatures. Basic Books. p. 138.

- Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 60. ISBN 0-85229-961-3.

The second tradition centred on Azeri, the literary language of the eastern Oğuz in western Persia, Iraq, and eastern Anatolia before the Ottoman conquest.

- Babinger, Franz (2008). "Nesīmī, Seyyid ʿImād al-Dīn". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Online. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- "Seyid Imadeddin Nesimi". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- Andrews, Walter G.; Black, Najaat; Kalpakli, Mehmet (1997). Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology. University of Texas Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 0-292-70472-0.

- Devellioğlu, Ferit (1993). Osmanlıca-Türkçe ansiklopedik lûgat: eski ve yeni harflerle. Ankara: Aydın Kitabevi. pp. 823–824. ISBN 975-7519-02-2.

- Cengiz, Halil Erdoğan (1972). Divan şiiri antolojisi. Milliyet Yayın Ltd. Şti. p. 149.

- Mélikoff, Irène (1992). Sur les Traces du Soufisme Turc: Recherches sur l'Islam Populaire en Anatolie. Editions Isis. pp. 163–174. ISBN 975-428-047-9.

- Turner, Bryan S. (2003). Islam: Critical Concepts in Sociology. Routledge. p. 284. ISBN 0-415-12347-X.

- Kuli-zade, Zümrüd (1970). Хуруфизм и его представители в Азербайджане. Baku: Elm. pp. 151–164.

- Safarli, Aliyar (1985). Imadəddin Nəsimi, Seçilmis Əsərləri. Baku: Maarif Publishing House. pp. 1–7.

- Baldick, Julian (2000). Mystical Islam: An Introduction to Sufism. I. B. Tauris. p. 103. ISBN 1-86064-631-X.

- Lambton, Ann K. S.; Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lewis, Bernard (1970). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 689. ISBN 0-521-29138-0.

- Minorksy, Vladimir (1942). "The Poetry of Shah Ismail". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 10 (4): 1053. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00090182.

- Aslanoğlu, İbrahim (1992). Şah İsmail Hatayî: Divan, Dehnâme, Nasihatnâme ve Anadolu Hatayîleri. Der Yayınları. p. 523.

- Safarli, Aliyar G.; Yusifli, Khalil (2005). "İmadeddin Nesimi" (PDF). Azerbaycan Eski Türk Edebiyatı (in Turkish). Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Turkey. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- The phrase is in some ways redolent of the earlier Sufi Mansur al-Hallaj's statement "ana al-Haqq" (أنا الحق), which means literally "I am the Truth" but also — because al-Haqq is one of the 99 names of God in Islamic tradition — "I am God".

- This device of employing double, and even completely opposite, meanings for the same word is known as tevriyye (توريه).

- "ChingizArt: Colors dedicated to Nesimi". Youtube.com. 2010-01-18. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- "Sculptures". www.azerbaijans.com (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Celebration | Cultural evening dedicated to the 600th anniversary of the death of the poet and philosopher Nassimi". UNESCO. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "En mémoire d'Imadaddin Nasimi à l'U.N.E.S.C.O." newsreelinthereal (in French). 2017-07-31. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "600th anniversary of Azerbaijani poet Nasimi's death marked at UNESCO headquarters". State News Agency of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 2018-11-26. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Opinion: 2019 will be the year of Nasimi in Azerbaijan". Common Space. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- "Meeting of Cabinet of Ministers dedicated to results of socioeconomic development of 2018 and objectives for future". Official web-site of President of Azerbaijan Republic. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- "President Ilham Aliyev declares 2019 as Year of Nasimi - Regional news". Ministry of Culture of Azerbaijan. 2019-01-11. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- "36th Term Meeting of the Permanent Council of TURKSOY held in Kastamonu :: TURKSOY". www.turksoy.org. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- "32939 Nasimi (1995 UN2)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "About Fikret Amirov". www.musigi-dunya.az. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- Федерация гимнастики Азербайджана

- "The progress of major overhaul and landscaping at the Sumgayit seaside park named after Nasimi". en.president.az. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Azerbaijan's new Nasimi Festival honours Sufi icon". euronews. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Azerbaijan to host Nasimi Festival of Poetry, Art and Spirituality organized by Heydar Aliyev Foundation - News | Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Azerbaijan". Ministry of Culture of Azerbaijan. 2018-09-05. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Inauguration of the Nasimi Festival takes place". heydar-aliyev-foundation.org. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "About | Nasimi Festival". www.nasimifestival.live. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Bust of great Azerbaijani poet Nasimi unveiled in Moscow". State News Agency of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- "Second grandiose Nasimi Festival of Poetry, Art and Spirituality to kick off in Azerbaijan". Trend.Az. 2019-09-27. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

- "Opening ceremony of the II Summer Camp of Diaspora Youth was held". State Committee on Work With Diaspora Of The Republic Of Azerbaijan. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- Shahana, Mushfig (2018-04-28). "Kinomuzun sözlü-musiqili naxışları". 525-ci qəzet (in Azerbaijani): 12 – via Azerbaijan National Library.