Modern history of Saudi Arabia

The Modern history of Saudi Arabia[1] begins with the unification of Saudi Arabia in a single kingdom in 1932.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Saudi Arabia |

|

|

|

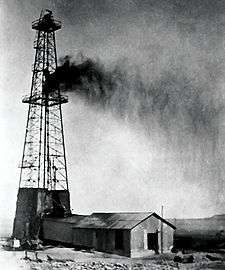

Discovery of oil

Abdul Aziz's military and political successes were not mirrored economically until vast reserves of oil were discovered in 1938 in the Al-Hasa region along the Persian Gulf coast. Prior to the discovery of oil, the main source of income for the government depended on the pilgrimage to Mecca, which was around 100,000 people per year in the late 1920s.

In the 1930s, Abdul Aziz granted an economic concession to the Standard Oil Company of California to drill for oil in his kingdom, after oil was found in nearby Bahrain in 1932. Oil wells were constructed in Dhahran in the late 1930s, and by 1939, the kingdom began to export oil.

During and after World War II, production of Saudi oil expanded, with much of the oil being sold to the Allies. Aramco (the Arabian American Oil Company) built an underwater pipeline to Bahrain to help increase oil flow in 1945. Between 1939 and 1953, oil revenues from Saudi Arabia increased from $7 million to over $200 million, and the kingdom began to be entirely dependent on oil income.[2]

Abdul Aziz died in 1953. Only sons of Abdul Aziz have, to date, ascended the Saudi throne. The number of children that he fathered is unknown, but it is believed that he had 22 wives and 37 sons, of whom six have become King.[3] In 1933, he chose his eldest surviving son Saud as his immediate successor.

The reigns of Saud & Faisal: 1953–1975

King Saud succeeded to the throne on his father's death in 1953. Oil provided Saudi Arabia with economic prosperity and a great deal of political leverage in the international community. The sudden wealth from increased production was a mixed blessing. Cultural life rapidly developed, primarily in the Hejaz, which was the center for newspapers and radio, but the large influx of foreigners increased the pre-existing propensity for xenophobia. At the same time, the government became increasingly wasteful and lavish. Despite the new wealth, extravagant spending led to governmental deficits and foreign borrowing in the 1950s.[4][5][6]

However, by the early 1960s an intense rivalry between the King and his half-brother, Faisal of Saudi Arabia emerged, fueled by doubts in the royal family over Saud's competence. This was of special concern given the Arab Cold War between Gamel Abdel Nasser's United Arab Republic and the pro-U.S. Arab monarchies. As a consequence, Saud was deposed in favor of Faisal in 1964.[7]

The mid-1960s saw external pressures generated by Saudi-Egyptian differences over Yemen. When civil war broke out in 1962 between Yemeni royalists and republicans, Egyptian forces entered Yemen to support the new republican government, while Saudi Arabia backed the royalists. Tensions subsided only after 1967, when Egypt withdrew its troops from Yemen. Saudi forces did not participate in the Six-Day (Arab-Israeli) War of June 1967, but the government later provided annual subsidies to Egypt, Jordan, and Syria to support their economies.[7][8]

In 1965 there was an exchange of territories between Saudi Arabia and Jordan in which Jordan gave up a relatively large area of inland desert in return for a small piece of seashore near Aqaba. The Saudi-Kuwaiti neutral zone was administratively partitioned in 1971, with each state continuing to share the petroleum resources of the former zone equally.[7]

.jpg)

The Saudi economy and infrastructure was developed with help from abroad, particularly from the United States, creating strong links between the two dissimilar countries, and considerable and problematic American presence in the Kingdom. The Saudi petroleum industry under the company of ARAMCO was built by American petroleum companies, U.S. construction companies such as Bechtel built much of the country's infrastructure, Trans World Airlines, built the Saudi passenger air service; the Ford Foundation modernized Saudi government; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the country's television and broadcast facilities and oversaw the development of its defense industry.[9]

During the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, Saudi Arabia participated in the Arab oil boycott of the United States and Netherlands. A member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Saudi Arabia had joined other member countries in moderate oil price increases beginning in 1971. After the 1973 war, the price of oil rose substantially, dramatically increasing Saudi Arabia's wealth and political influence.[7]

Faisal was assassinated in 1975 by his nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musa'id.[10]

Khalid's reign: 1975–1982

King Khalid succeeded his half-brother King Faisal. During Khalid's reign economic and social development continued at an extremely rapid rate, revolutionizing the infrastructure and educational system of the country; in foreign policy, close ties with the US developed. In 1979, two events occurred which the Al Saud perceived as threatening the régime, and which had a long-term influence on Saudi foreign and domestic policy:

- The first was the Iranian Islamic revolution. It was feared that the country's Shi'ite minority in the Eastern Province (which is also the location of the oil fields) – might rebel under the influence of their Iranian co-religionists. In fact several anti-government riots took place in the region in 1979 and 1980.

- The second event the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca by Islamist extremists. The militants involved were in part angered by what they considered to be the corruption and un-Islamic nature of the Saudi regime.[5][6][7][11]

Part of the response of the royal family involved enforcing a much stricter observance of Islamic and traditional Saudi norms in the country (for example, the closure of cinemas) and giving the Ulema a greater role in government. Neither entirely succeeded as Islamism continued to grow in strength.[5][6][7][11] King Khalid empowered Crown Prince Fahd to oversee many aspects of the government's international and domestic affairs. Economic development continued rapidly under King Khalid, and the kingdom assumed a more influential role in regional politics and international economic and financial matters.[7]

During the 1970s and 1980s more than 45,000 Saudi students per year went to the United States, while more than 200,000 Americans have lived and worked in the Kingdom since the discovery of oil.[9]

A tentative agreement on the partition of the Saudi-Iraqi neutral zone was reached in 1981. The governments finalized the partition in 1983.[7]

King Khalid died in June 1982.[7]

Fahd's reign: 1982–2005

Khalid was succeeded by his brother King Fahd in 1982, who maintained Saudi Arabia's foreign policy of close cooperation with the United States and increased purchases of sophisticated military equipment from the United States and Britain. In the 1970s and '80s, the country had become the largest oil producer in the world. Oil revenues were crucial to Saudi society as its economy was changed by the extraordinary wealth it generated and which was channeled through the government. Urbanization, mass public education, the presence of numerous foreign workers, and access to new media all affected Saudi values. While society changed profoundly, political processes did not. Real power continued to be held almost exclusively by the royal family, leading to disaffection with many Saudis who began to look for wider participation in government.[7]

Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 Saudi Arabia joined the anti-Iraq Coalition and King Fahd, fearing an attack from Iraq, invited American and Coalition soldiers to be stationed in Saudi Arabia. Saudi troops and aircraft took part in the subsequent military operations. However, allowing Coalition forces to be based in the country proved to be one of the issues that has led to an increase in Islamic terrorism in Saudi Arabia, as well as Islamic terrorist attacks in Western countries by Saudi nationals – the September 11 attacks in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania being the most prominent example.[7][12]

Islamism was not the only source of hostility to the regime. Although now extremely wealthy, the country's economy was near stagnant, which, combined with a growth in unemployment, contributed to disquiet in the country, and was reflected in a subsequent rise in civil unrest, and discontent with the royal family. In response, a number of limited 'reforms' were initiated (such as the Basic Law). However, the royal family's dilemma was to respond to dissent while making as few actual changes in the status quo as possible. Fahd made it clear that he did not have democracy in mind: "A system based on elections is not consistent with our Islamic creed, which [approves of] government by consultation [shūrā]."[7]

In 1995, Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke and the Crown Prince, Prince Abdullah assumed day-to-day responsibility for the government, albeit his authority was hindered by conflict with Fahd's full brothers, the Sudairi 'clan'. Abdullah continued the policy of mild reform and greater openness, but in addition, adopted a foreign policy distancing the kingdom from the United States. In 2003, Saudi Arabia refused to support the U.S. and its allies in the invasion of Iraq.[7]

In July 1997, King Fahd increased the members of the Consultative Council from 60 to 90, although they were still all appointed. In October 1999, the King allowed twenty Saudi women to attend a session of the Consultative Council for the first time. Three months after a British man claimed he had been tortured by Saudi police, a revised criminal code was issued in May 2002. It included a ban on torture and the right of suspects to legal representation, but rights campaigners stated that violations continued. In April 2003, the US announced it was to pull out almost all its troops from Saudi Arabia, ending a military presence dating back to the 1991 Gulf war. Both countries stressed that they would remain firm allies.

Signs of discontent continued. Terrorist activity increased dramatically in 2003, with the Riyadh compound bombings and other attacks, which prompted the government to take much more stringent action against terrorism.[11] Suicide bombers killed 35 people at housing compounds for Westerners in Riyadh hours before U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell flew in for planned visit in May 2003. More than 300 Saudi intellectuals – women as well as men – signed a petition in September 2003, calling for far-reaching political reforms. A month later, police had to break up an unprecedented rally in the centre of Riyadh calling for political reform. More than 270 people were arrested. In November, a suicide attack by suspected al-Qaeda militants on a residential compound in Riyadh left 17 dead and scores injured. The King responded by granting the Consultative Council the ability it to propose legislation.

There was a serious escalation in militant violence in 2004. In April four police officers and a security officer were killed in attacks near Riyadh. A car bomb at security forces' HQ in Riyadh killed four, wounds 148. A group linked to al-Qaeda claimed responsibility. In May, an attack at a petrochemical site in Yanbu killed five foreigners. Another attack and hostage-taking at an oil company compound in Khobar saw 22 people killed. In June, there were three gun attacks in Riyadh within a week, leaving two Americans and a BBC cameraman dead. The same week, a U.S. engineer was abducted and beheaded, his filmed death caused revulsion in America. Security forces killed the local al-Qaeda leader shortly afterwards, but an amnesty for militants which followed had only limited effect despite a fall in militant activity. In December, an attack on the U.S. consulate in Jeddah led to five staff and four attackers being killed. Two car bombs exploded in central Riyadh and security forces killed seven suspects in a subsequent raid.[13]

Abdullah's reign: 2005 to 2015

In 2005, King Fahd died and his half-brother, Abdullah ascended to the throne. Despite growing calls for change, the king continued the policy of moderate reform.[14]

The country's continued reliance on oil revenue is of particular concern.[15] King Abdullah pursued a policy of limited deregulation, privatization, and seeking foreign investment. In November 2005, following 12 years of talks, the World Trade Organization gave the green light to Saudi Arabia's membership.[16]

In December 2006, Saudi Arabia pressured Britain into halting a fraud investigation into the £43bn Al-Yamamah arms deal with Saudi Arabia.[17] Then, in September 2007, Saudi Arabia agreed a deal to buy 72 Eurofighter Typhoon combat jets from Britain. A British High Court later ruled that the British government had acted unlawfully in dropping the corruption inquiry, but this was overturned by the British House of Lords in July 2008 because Saudi Arabia had threatened to withdraw cooperation with Britain on security matters.[18]

Terrorist attacks continued to be a major problem.[19] In September 2005, five gunmen and three police officers were killed in clashes in the eastern city of Dammam. The government claimed it had foiled a planned suicide bomb attack on a major oil-processing plant at Abqaiq in February 2006. Six men allegedly linked to al-Qaeda were killed in a shootout with police in Riyadh in June 2006. Four French nationals were killed in a suspected terror attack near the popular tourist destination of Madain Saleh in February 2007.

Saudi justice came under criticism over the Qatif rape case in which a 19-year-old rape victim was sentenced to 6 months in prison and 90 lashes. The king eventually issued a pardon. A ban had to be placed on the Mutaween (religious police) from detaining suspects as they had come under increasing criticism over the number of deaths in custody. A royal decree ordered an overhaul of the judicial system in October 2007. In December 2007, authorities announced the arrest of a group of men suspected of planning attacks on holy sites during the Hajj pilgrimage. In February 2009, Interpol issued security alerts for 85 men suspected of plotting attacks in Saudi Arabia, in its largest group alert. All but two were Saudis.[7][20] In February 2009, King Abdullah sacked the head of religious police, his most senior judge and the head of the central bank in a rare government reshuffle. He also appointed the country's first woman minister.

In July 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama arrived in Saudi Arabia and held talks with King Abdullah at the start of a Middle East tour aimed at increasing U.S. engagement with the Islamic world. In October 2010, U.S. officials confirmed a plan to sell $60 billion worth of arms to Saudi Arabia – the most lucrative single arms deal in US history.[21] Relations were hurt over the United States diplomatic cables leak by the whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks in December 2010. They suggested that the USA was concerned that Saudi Arabia was the most significant source of funding for Sunni terrorist groups worldwide. Nevertheless, a major sale of U.S. fighter jets to Saudi Arabia was confirmed in December 2011.

Security measures included a policy of mass arrests.[22] In April 2007, Saudi police claimed they had arrested 172 terror suspects, some of whom were allegedly trained as pilots for suicide missions. In April 2009, police said they had arrested 11 al-Qaeda militants who were allegedly planning attacks on police installations, armed robberies and kidnappings. A court issued verdicts in the first explicit terrorism trial for al-Qaeda militants in the country. Officials said 330 people had been put on trial, but did not specify how many had been found guilty. In August 2009, Saudi Arabia said it had arrested 44 more suspected militants with alleged links to al-Qaeda. A year later, officials announced the arrest of 149 militants over an eight months period, most of them allegedly belonging to al-Qaeda. In April 2012, fifty men suspected of having links to al-Qaeda went on trial. Charges included the 2003 bombing of an expatriates' compound.[23]

As the Arab Spring unrest and protests began to spread across the Arab world and at a much more modest level in Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah announced an increase in welfare spending amounting to $10.7 billion. This included funding to offset high inflation, aid for young unemployed people and Saudi citizens studying abroad, as well as writing off some loans. State employees saw their incomes increase by 15 per cent, and additional cash was made available for housing loans. No political reforms were announced as part of the package, though some prisoners indicted for financial crimes were pardoned.[24] After a number of small demonstrations in the mainly Shia areas of the east, where the Qatif conflict had started in 1979, public protests were banned in March 2011, and King Abdullah warned that threats to the nation's security and stability would not be tolerated.[25]

At the same time Saudi troops were sent to participate in the crackdown on unrest in Bahrain. King Abdullah gave asylum to deposed President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia and telephoned President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt (prior to his deposition) to offer his support.[26] In July 2012, security forces detained several people in Qatif, Eastern Province, after witnessing police open fire on Shia protesters demanding the release of Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr and others. Two people were killed at a rally against his arrest earlier in the month. Human-rights activists Mohammad al-Qahtani and Abdullah al-Hamid were put on trial in September 2012; the former was charged with setting up an unlicensed organisation.[27][28]

In June 2011 Saudi women mounted a symbolic protest drive in defiance of the ban on female car drivers. A few months later, King Abdullah announced more rights for women, including the right to vote, stand in municipal elections and to be appointed to the Consultative Assembly of Saudi Arabia (Shura Council) – the most influential political body. In September 2011, the king overturned a sentence of 10 lashes on a woman who was found guilty of driving – the first time that a legal punishment had been handed down for violation of the ban on women drivers.[29] Saudi Arabia agreed to allow its women athletes to compete in the 2012 Olympics for the first time. Another women's driving protest took place on 26 October 2013, when 60 Saudi women drove their cars in defiance of the de facto ban. Authorities responded by stating that they would deal with such violations forcefully. An online petition in favour of women's right to drive gathered thousands of signatures.[30]

The Saudi anti male-guardianship campaign also started during Abdullah's reign, when in August 2006, Saudi women's rights activist Wajeha al-Huwaider, who had already been banned by Saudi authorities from publishing her opinions in Saudi media in 2003, was arrested after holding a women's rights street protest.[31] She protested against male guardianship again in June 2009, by trying unsuccessfully three times to enter Bahrain without permission from her male guardian.[32] The campaign continued in late 2011, during the 2011–12 Saudi Arabian protests, when Saudi women started a campaign against the Saudi Ministry of Labor requirement for guardian approval for employment. The group contacted the media and argued that women's equality is established in the eighth article of the Saudi Arabian constitution, and that Islamic scholars generally do not see male guardian approval as a requirement for a women to be employed.[33][34] The group held workshops on the issue and studied Islamic religious arguments[35][36] in relation to male guardianship.[37]

In August 2013, Saudi Arabia emerged as a supporter of the Egyptian military leaders that were cracking down on Islamists. They openly supported the leaders with their wealth received from oil mining and used their diplomatic presence to aid Egypt in resisting pro-Western influence. Just a month later, word spread that President Obama intended to keep up his presence in the Middle East, and continue trying to work towards preventing the development of nuclear weapons in Iran. Saudi Arabia, like many other gulf states, saw Iran to be a large threat to the area with its growing nuclear program.[38][39]

Around the end of the month of April in 2014, President Obama announced that he would travel to Saudi Arabia in March in an effort to mend the relationship between the two countries. Saudi Arabia and the gulf states have been frustrated with policies that the United States has been placing on Syria and Iran.[38][40] Iran especially, has been expressing desire to be relieved of the Iran Sanctions Act. Obama's visit to Saudi Arabia proved to be successful as Obama reassured King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia that America still intended to strengthen Saudi Arabia's standing in the Syrian war. There were no concrete details of the meeting, but speculation from the aides has presented information on the meeting. President Obama's visit to the Middle East ended on the 30th of March with a private ceremony, and he returned home. Still there was little word about what really was said at the convening.[39]

During the month of April in 2014, there has been a severe outbreak of Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS. MERS has been present in Saudi Arabia since 2012, and has affected over 200 people since then. There have been nearly 100 deaths as a result of MERS, and due to the new cases that have reemerged, King Abdullah has replaced Arabia's health minister. From April 21, 2014 to the 25th, there have been almost 100 new cases reported and six deaths from MERS.[30]

In May 2014, on the 6th it was reported that 62 military men were arrested because of alleged accusations for having ties linked to terrorist groups in Yemen and Syria. Saudi Arabia believes that they were planning an attack on Saudi Arabia in the form of assassinations of Arabian officials. Maj. Gen. Mansour al-Turki, the spokesman of the interior ministry program states that the men had communicated with members of the Al Qaeda terrorist group, and they were in the process of planning on to make trades and smuggling weapons for an attack on the Saudi Arabia's clerics and government officials.[39][30]

On 2 January 2015, Abdullah was hospitalized for pneumonia and died on 22 January, and was succeeded by his brother Salman the following day.

References

- "The History of Saudi Arabia". SaudiEmbassy.net. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East, A History. McGraw Hill. p. 700. ISBN 0-07-244233-6.

- "New Saudi Rules on Succession: - The Washington Institute for Near East Policy". Washingtoninstitute.org. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online: "History of Arabia" retrieved 18 January 2011

- al-Rasheed, Madawi, A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge University Press, 2002) ISBN 0-521-64335-X

- Robert Lacey, The Kingdom: Arabia & The House of Sa'ud, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc, 1981 (Hard Cover) and Avon Books, 1981 (Soft Cover). Library of Congress: 81-83741 ISBN 0-380-61762-5

- Joshua Teitelbaum. "Saudi Arabia History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- "Background note: Saudi Arabia". US State Department. 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- Wright, Lawrence, Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, by Lawrence Wright, NY, Knopf, 2006, p.152

- Robert Lacey, The Kingdom: Arabia and the House of Saud (Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich Publishing: New York, 1981) p. 426.

- 'Jihad in Saudi Arabia: Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979' by Thomas Hegghammer, 2010, Cambridge Middle East Studies ISBN 978-0-521-73236-9

- Hegghammer 2010, p. 112

- Cordesman, Anthony H. (2009). Saudi Arabia: national security in a troubled region. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-313-38076-1.

- "Saudi Arabia | The Middle East Channel". Mideast.foreignpolicy.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-22. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- Lahn, Glada; Stevens, Paul (December 2011). Burning Oil to Keep Cool: The Hidden Energy Crisis in Saudi Arabia. Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs). ISBN 978-1-86203-259-0.

- "Accession status: Saudi Arabia". WTO. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- "FRONTLINE/WORLD: The Business of Bribes: More on the Al-Yamamah Arms Deal". PBS. 2009-04-07. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- David Pallister (2007-05-29). "The arms deal they called the dove: how Britain grasped the biggest prize". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- Carey, Glen (2010-09-29). "Saudi Arabia Has Prevented 220 Terrorist Attacks, Saudi Press Agency Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- Dickey, Christopher (21 March 2009). "Saudi King Abdullah's Sudden Push for Reforms". Newsweek. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- "Saudi deals boosted US arms sales to record $66.3 bln in 2011". Reuters India. 27 August 2012. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- "The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Initiatives and Actions to Combat Terrorism" (PDF). May 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009.

- McDermott, Roger. "Mass Arrests of al-Qaeda Suspects in Saudi Arabia Illustrate Security Threat from Yemen". Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- "Saudi king announces new benefits". Al Jazeera English. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- Fisk, Robert (5 May 2011). "Saudis mobilise thousands of troops to quell growing revolt". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Black, Ian (31 January 2011). "Egypt Protests could spread to other countries". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "Saudi Arabia accused of repression after Arab Spring". BBC News. 1 December 2011. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- Kevin Sullivan, The Washington Post (23 October 2012). "Saudi Arabia's secret Arab Spring". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- MacFarquhar, Neil (17 June 2011). "Women in Saudi Arabia Drive in Protest of Law". The New York Times.

- "Saudi Arabia". New York Times. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Dankowitz, Aluma (28 December 2006). "Saudi Writer and Journalist Wajeha Al-Huwaider Fights for Women's Rights". Middle East Media Research Institute. Archived from the original on 26 May 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Jamjoom, Mohammed; Escobedo, Tricia (10 July 2009). "Saudi woman activist demands right to travel". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 May 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- Ghanem, Sharifa (17 January 2012). "Saudi women battle male guardianship laws, push for rights". Bikya Masr. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Hawari, Walaa (14 November 2011). "Women intensify campaign against legal guardian". Arab News. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- al-Munajjid, Muhammad Saalih (General Supervisor) (25 November 2006). "She married without her wali's consent and the marriage contract was done without her being present – islamqa.info". islamqa.info. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- The Hanafi School and the issue of Wali

- "Thousands of Saudis sign petition to end male guardianship of women". The Guardian. 26 September 2016. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Fischetti, P (1997). Arab-Americans. Washington: Washington: Educational Extension Systems.

- "Affairs". Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original on 2016-07-15. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- Kirkpatrick, David. "3 Gulf Countries Pull Ambassadors From Qatar Over Its Support of Islamists". New York Times.