Military of the Ming dynasty

The military of the Ming dynasty was the military apparatus of China from 1368 to 1644. It was founded in 1368 during the Red Turban Rebellion by the Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang. The military was initially organised along largely hereditary lines and soldiers were meant to serve in self-sufficient agricultural communities. They were grouped into guards (wei) and battalions (suo), otherwise known as the wei-suo system. This hereditary guard battalion system went into decline around 1450 and was discarded in favor of mercenaries a century later.

| Military of the Ming dynasty | |

|---|---|

Ming cavalry, as depicted in the Departure Herald | |

| Active | 1368–1662 |

| Allegiance | Empire of the Great Ming (China) |

| Size | c. 845,000 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Hongwu Emperor Mu Ying Yongle Emperor Qi Jiguang Yuan Chonghuan |

Background

The Ming Emperors from Hongwu to Zhengde continued policies of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty such as hereditary military institutions, dressing themselves and their guards in Mongol-style clothing and hats, promoting archery and horseback riding, and having large numbers of Mongols serve in the Ming military. Until the late 16th century Mongols still constituted one-in-three officers serving in capital forces like the Embroidered Uniform Guard, and other peoples such as Jurchens were also prominent.[1][2] A cavalry-based army modeled on the Yuan military was favoured by the Hongwu and Yongle Emperors.[3]

At the Guozijian Academy, equestrianism and archery were emphasized by the Ming Hongwu Emperor in addition to Confucian classics, also being required in the Imperial Examinations.[4][5]:267[6][7][8][9] Archery and equestrianism were added to the exam by Hongwu in 1370 just as archery and equestrianism were required for non-military officials at the 武舉 College of War in 1162 by the Song Emperor Xiaozong.[10]

Guard battalion system

The Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang set up a system of hereditary soldiery inspired by Mongol-style garrisons and the fubing system of the Northern Wei, Sui and Tang dynasties.[11] Hereditary soldiers were meant to be self-sufficient. They provided their own food via military farms (tun tian) and rotated into training and military posts such as the capital, where specialized drilling with firearms was provided.[12]

These hereditary soldiers were grouped into guards (wei) and battalions (suo), otherwise known as the wei-suo system. A guard consisted of 5,600 men, each guard was divided into battalions of 1,120 men (qiānhù), each battalion contained 10 companies of 112 men (bǎihù), each company contained two platoons of 56 men (zǒngqí), and each platoon contained five squads of 11 or 12 men (xiǎoqí).[12]

Most of the soldiers in Ming’s army came from military households, which consisted of about 20 percent of households in the early Ming period.[13] Each military household was required to provide one man to serve in the army. If that man died, the household was required to send another.[14]

There were four ways to become a military household. The first was for the family to be descended from a “fellow campaigner” who took part in the wars of the Ming founder.[15] The family could also be descended from a soldier serving one of the enemies of the Ming founder but became incorporated into Ming troops after defeat.[15] Those convicted of criminal offences could also be sentenced to serve in the military.[15] But by the fifteenth century, criminal conviction no longer resulted in a normal household's conversion into military household. Punitive service was made non-hereditary.[15] Lastly, soldiers were also recruited through a draft.[15]

Social status and decline

Soldiering was one of the lowest professions in the Ming dynasty. Military officers were not only subordinate to civil officials, but generals and soldiers alike were degraded, treated with fear, suspicion, and distaste. Military service enjoyed far less prestige than its civil counterpart due to its hereditary status and because most soldiers were illiterate.[16]

The guard battalion system went into decline from 1450 to 1550 and the military capacity of hereditary soldiers declined substantially due to corruption and mismanagement. Some officers used their soldiers as construction gangs, some were too oppressive, others were too old and unfit for service, and many did not observe the proper rotational drilling schedule. In the 16th century official registers listed three million hereditary soldiers, but contemporary observers noted that the actual number of troops was around 845,000, and of that only about 30,000 cavalry.[17] Soldiers were also assigned tasks unrelated to warfare and combat. One of the primary military assignments in the early stages of the Ming empire was farming plots of land.[18] Soldiers were often subject to exploitation from higher-ups in the army; they did menial tasks such as chopping down trees and picking herbs for the sole benefit of their superiors.[19] The Ming sometimes utilized soldiers as transport workers to move grain and other foodstuffs throughout the empire.[19] Soldiers were essentially no different than hired help due to the fact that they were often assigned to various menial tasks requiring manual labor.[20] Officers were known to seize the lands of military colonies and convert them into their private estates, and subsequently force their troops into becoming their serfs. Other officers accepted bribes from soldiers to be exempted from military drill, and used other troops as menial labour. Corruption was so lucrative that the sons of merchants were known to bribe officials for appointments as army officers so as to exhort bribes from soldiers in exchange for drill exemption, or to register their own servants as soldiers so as to embezzle their rations. Desertion from the weisuo became commonplace.[11]

The military was not the most profitable occupation and thus soldiers had to rely on other means to make money aside from the salary given by the government. The most straightforward method was to kill more enemy soldiers, which would grant them a reward for each soldier killed in battle.[21] Some soldiers defected from the army and turned to banditry because they did not have enough food to eat.[22]

Complicating the matter was the fact that soldiers of the same rank did not share the same authority. Soldiers who had more wealth were able to bribe their superiors with money and other gifts increased their standing and status within the army.[23]

Since most did not want to serve in the army, family members who chose to be soldiers might get some sort of compensation from other male family members. For example, they could become the next "descent-line heir" even if they were not the eldest son, as was tradition, by volunteering to enlist. The "descent-line heir" was the right to hold a special ritual role within the clan and hence enhance one's social status since the heir would inherit his father’s privileges.[24] In a military family, soldiers who were assigned to locations far away from their ancestral homes often saw their relationships with their extended family decline.[25] To counter this, subsidies were granted to serving soldiers in an attempt to lower the desertion rate of soldiers serving in the family and help maintain a connection between the serving soldier’s immediate family with their ancestral one.[26] The subsidy gave a reason for the immediate family members of the soldier to regularly visit their ancestral homes to collect payment and thereby maintain their relationship.[26]

However certain regions were known to have differing views of military service, such as Yiwu County where Qi Jiguang recruited his troops. Young men with varying backgrounds ranging from peasants to that of a national university student in those areas chose to join the army.[27] A major reason for the popularity of military service in this area was the potential for quick advancement through military success.[28]

Navy

The navy was not a separate entity during the Ming era and was part of the guard battalion system. Every coastal guard battalion was allotted 50 ships for maritime defense. The Ming also set up naval palisades, beacon towers, strategic forts, and irregular military units and warships.[29] Unfortunately these defensive measures proved largely inadequate against pirate raids, and conditions continued to deteriorate until the Jiajing wokou raids were ended by Qi Jiguang and Yu Dayou.[30] Shaolin monks also took part in anti-piracy campaigns, most notably between 21 and 31 July 1553 at Wengjiagang, when a group of 120 monks exterminated over 100 pirates with only 4 monks dead.[31]

Ming naval activity was noticeably subdued. Its founder, the Hongwu Emperor, emphasized that "not even a plank is to be allowed into the sea."[30] He did however establish the Longjiang Shipyards of Nanjing that would grow into the birthplace of the Treasure Fleet. The Ming Navy was also equipped with firearms, making them one of the earliest gunpowder armed navies at the time. It was therefore described by Lo and Elleman as the world's "foremost" navy of that era.

The Hongwu Emperor ordered the formation of 56 military stations (wei), each with a strength of 50 warships and 5000 seamen. However most of these seem to have been left under-strength. The size of the navy was greatly expanded by the Yongle Emperor. The Ming Navy was divided into the Imperial fleet stationed in Nanjing, two coastal defence squadrons, the high-seas fleet used by Zheng He, and the grain transportation fleet.[33]

After the period of maritime activity during the treasure voyages under the Yongle Emperor, the official policy towards naval expansion swayed between active restriction to ambivalence.[30] Despite Ming ambivalence towards naval affairs, the Chinese treasure fleet was still able to dominate other Asian navies, which enabled the Ming to send governors to rule in Luzon and Palembang as well as depose and enthrone puppet rulers in Sri Lanka and the Bataks. In 1521, at the Battle of Tunmen a squadron of Ming naval junks defeated a Portuguese caravel fleet, which was followed by another Ming victory against a Portuguese fleet at the Battle of Xicaowan in 1522. In 1633, a Ming navy defeated a Dutch and Chinese pirate fleet during the Battle of Liaoluo Bay. A large number of military treatises, including extensive discussions of naval warfare, were written during the Ming period, including the Wubei Zhi and Jixiao Xinshu.[34] Additionally, shipwrecks have been excavated in the South China Sea, including wrecks of Chinese trade and war ships that sank around 1377 and 1645.[35]

Housemen

Housemen were soldiers who privately served the higher-ups in the army. The addition of housemen in the army challenged core ideals within the army as housemen emphasized the concept of self-interest as opposed to the previous concept of loyalty to the empire.[36]

Command structure

The guard battalions outside the capital were placed under local provincial military commanders. Those in Beijing were placed under the joint command of the Ministry for War and five grand military commanders, which reflected the separation of power and command. The Ministry issued orders to be carried out by the commanders. [29]

Some officers were recruited through the military version of the imperial examinations, which emphasized horse archery, but not enough to impose a quality standard. These exams did however produce a few notable individuals such as Qi Jiguang and Yu Dayou.[37]

In the late Ming dynasty, Ming army units had become dominated by hereditary officers who would spend long periods of ten or twelve years in command instead of the usual practice of constant rotation, and the Central Military Command had lost much of its control over regional armies. Zongdu Junwu, or Supreme Commanders, were appointed throughout the empire to oversee the fiscal and military affairs in the area of his jurisdiction, but they became increasingly autonomous in later periods.[11][38]

Princes of the Imperial family were also granted substantial military authority in strategic points around the empire. Each was granted an estate with the power to recruit military officers for their personal staff (this was restricted in 1395) and held total judicial authority over them. This ancient system, intended to provide military experience before deployment, had not been used in China for a thousand years.[39] Princes were also dispatched to join campaigns with their personal bodyguards. Zhu Di, Prince of Yan, impressed the Hongwu Emperor with his command of the 1390 campaign against the Mongols under Nayir Bukha and was allowed to retain command of the 10,000 Mongol soldiers he had captured. This later aided the prince in his usurpation of the throne. In some cases the princes were appointed to fill vacant command positions. Zhu Gang, the Prince of Qin, was sent to build military colonies (tuntian) beyond the Great Wall.[40] Princes were granted an escort guard (hu-wei ping) under their personal control, while a court-appointed officer commanded the shou-chen ping or garrison force, over which the princes only had authority during emergencies declared by the Emperor. This dual chain of command was meant to prevent a coup d'etat in the capital. The garrison force could only be deployed with an order carrying both the Emperor's and the Prince's seal. The Regional Military Commission armies were then used to check the princes' military power. Many princes amassed large bodyguard forces and transferred regular soldiers to their personal command without authorisation anyway, using them on campaign.[41] The authority of princes was curtailed by the Jianwen Emperor. When the Yongle Emperor came to power, he further purged his brothers on trumped up charges and abolished most of the princely guards; by the dynasty's end there were less than a dozen extant. He also established a hereditary military nobility from his top generals during his usurpation, both Han Chinese and Mongol. They were however denied long-term commands so as to prevent personal power bases from forming.[42]

Mercenaries and salaried soldiers

After the decline of the guard battalion system, the Ming army came to rely more upon mercenaries to improve efficiency and lighten local military burdens.[16]

Hired soldiers helped bolster the ranks of the army by allowing armies to have more members, aside from the active members of the military households. These soldiers came from multiple sources; some came from inactive members of military households, the ones that were not registered as the serving soldier of the family, as well as other members of the empire that were not obligated to serve in the army.[43] Non-hereditary troops were a fairly distinct and unified group within the army as they would rebel and riot together whenever they had problems with how they were treated or whenever their salaries were not paid on time.[44]

As the social status of soldiers was not high, mercenaries usually came from the desperate underclass of society such as amnestied bandits or vagabonds. The quality of these troops was highly diverse, depending on their regional origins. Peasant militia were generally regarded as more reliable than full-time soldiers, who were described as useless. Commanders refrained from training or reforming the mercenary armies for fear of provoking riots, and Ming generals started to fight personally on the front lines with handpicked battalions of elite bodyguards rather than attempt to control the hordes of unreliable mercenaries.[45]

By the 1570s, the Ming army had largely transitioned to a mercenary force.[37][12]

Origins of soldiers

Mongol mercenaries

The Hongwu Emperor incorporated northern non-Chinese peoples such as the Mongols and Jurchens into the army.[46] Mongols were retained by the Ming within its territory.[47][48] Most of these soldiers were stationed on the northern frontier, however they were deployed in the south as well in some cases such as in Guangxi against Miao rebellions.[49]

The Mongols were able to obtain government rewards such as land grants and opportunities to rise up in the military, but they suffered general discrimination as an ethnic minority. Mongol soldiers and leaders were never given independent control and always answered to a Chinese general, however the Chinese supervisory role was mostly a nominal one, so Mongol troops behaved as though they were independent mercenaries or personal retinues. This relationship lasted throughout the entire dynasty, and even in the late Ming, general retinues included Mongol horsemen in their company.[50][48]

Ming dynasty writer and historian Zhu Guozhen (1558-1632) remarked on how the Ming dynasty managed to successfully control Mongols who surrendered to the Ming and were relocated and deported into China to serve in military matters unlike the Eastern Han dynasty and Western Jin dynasty whose unsuccessfully management of the surrendered and defeated barbarians of the Five Barbarians they imported into northern China who learned to study history and this led to rebellion in the Uprising of the Five Barbarians : Late during the Eastern Han (25-220 C.E.), surrendering barbarians were settled in the hinterlands [of China]. In time, they learned to study and grew conversant with [matters of the] past and present. As a result, during the Jin dynasty (265-419), there occurred the Revolt of the Five Barbarian [Tribes](late in the third and early in the fourth centuries C.E.).184 During our dynasty, surrendering barbarians were relocated to the hinterlands in great numbers. Because [the court] was generous in its stipends and awards, [the Mongols are content to] merely amuse themselves with archery and hunting. The brave185 among them gain recognition through [service in] the military. [They] serve as assistant regional commanders and regional vice commanders. Although they do not hold the seals of command, they may serve as senior officers. Some among those who receive investiture in the nobility of merit may occasionally hold the seals of command. However [because the court] places heavy emphasis on maintaining centralized control of the armies, [the Mongols] do not dare commit misdeeds. As a consequence, during the Tumu Incident, while there was unrest everywhere, it still did not amount to a major revolt. Additionally, [the Mongols] were relocated to Guangdong and Guangxi on military campaign. Thus, for more than 200 years, we have had peace throughout the realm. The dynastic forefathers' policies are the product of successive generations of guarding against the unexpected. [Our policies] are more thorough than those of the Han. The foundations of merit surpass the Sima family (founders of the Eastern Jin) ten thousand fold. In a word, one cannot generalize [about the policies towards surrendering barbarians].186[51]

Wolf troops

The Ming dynasty sometimes employed "martial minorities" such as the "wolf troops" of Guangxi as shock infantry.[52]

Northern soldiers

Qi Jiguang described northern soldiers as stupid and impatient. When he tried to introduce muskets in the north, the soldiers there were adamant in continuing to use fire lances.[53]

Recruits from Liaodong, and people from Liaodong in general, were considered untrustworthy, unruly, and little better than thugs.[54] In Liaodong as military service and command became hereditary, vassalage-like personal bonds of loyalty grew between officers, their subordinates and troops. This military caste gravitated toward the Jurchen tribal chieftains rather than the bureaucrats of the capital.[38]

Southern soldiers

Troops of Southern Chinese extract seem to have fared better in infantry and naval combat than those in the north. They have at least on one occasion been called "ocean imps" by Northern Chinese.[55] Southerners were also intensely mistrusted by Northern Chinese. During the Wuqiao Mutiny of 1633, the northern Chinese rebels purged the "southerners" in their midst, who were suspected of aiding the Ming.[56]

There was a lingua franca used among troops known in English as junjiahua, based on Northern Chinese dialects, it can be found into the present day throughout southern China, having been passed down by descendants of Ming dynasty soldiers.[57]

Weapons

The spear was the most common weapon and soldiers were given comprehensive training in spear combat, both as individuals and in formation. A complete spear regimen lasted one hundred days.[58]

The dao, also called a saber, is a Chinese category for single edged, curved swords. It was the basic close fighting weapon of the Ming dynasty.[59] The jian, also known as a long sword, is a Chinese category for straight double-edged swords. It experienced a resurgence during the Yuan dynasty but fell out of favor again in the Ming. The jian remained in use by a small number of arms specialists but was otherwise known for its qualities as a marker of scholarly refinement.[60]

The "Horse Beheading Dao" was described in Ming sources as a 96 cm blade attached to a 128 cm shaft, essentially a glaive weapon. It's speculated that the Swede Frederick Coyett was talking about this weapon when he described Zheng Chenggong's troops wielding "with both hands a formidable battle-sword fixed to a stick half the length of a man".[61]

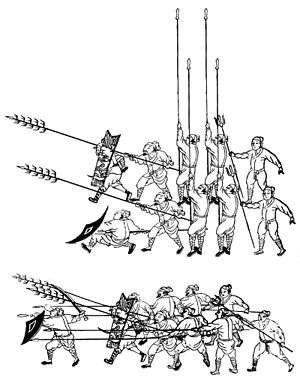

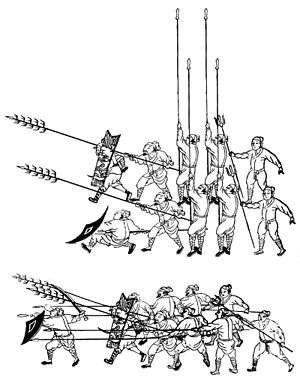

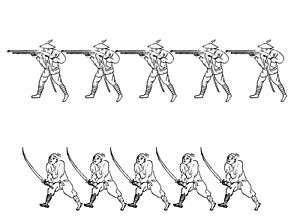

Qi Jiguang deployed his soldiers in a 12-man 'mandarin duck' formation, which consisted of four pikemen, two men carrying daos with a great and small shield, two 'wolf brush' wielders, a rearguard officer, and a porter.[62] This system bears some resemblance to European systems (pike and shot) developing in England where formations of arquebusiers would be protected by a group of pikemen.[63] Volley fire was also used.[64]

Archery with bow and crossbow was considered a central skill despite the rise of gunpowder weapons.[37]

Ming dao

Ming dao Ming soldiers carrying a dao and jian

Ming soldiers carrying a dao and jian Ming soldier carrying a jian

Ming soldier carrying a jian

Armour

During the Ming dynasty, most soldiers did not wear armour, which was reserved for officers and a small portion of the several hundred thousand strong army.[65] Horse armour was only used for a small portion of cavalry, which was itself a minute portion of the Ming army.[66]

Brigandine armour was introduced during the Ming era and consisted of riveted plates covered with fabric.[66]

Partial plate armour in the form of a cuirass sewn together with fabric is mentioned in the Wubei Yaolue, 1638. It's not known how common plate armour was during the Ming dynasty, and no other source mentions it.[67]

Although armour never lost all meaning during the Ming dynasty, it became less and less important as the power of firearms became apparent. It was already acknowledged by the early Ming artillery officer Jiao Yu that guns "were found to behave like flying dragons, able to penetrate layers of armor."[68] Fully armoured soldiers could and were killed by guns. The Ming marshal Cai was one such victim. An account from the enemy side states, "Our troops used fire tubes to shoot and fell him, and the great army quickly lifted him and carried him back to his fortifications."[69] It's possible that Chinese armour had some success in blocking musket balls later on during the Ming dynasty. According to the Japanese, during the Battle of Jiksan, the Chinese wore armour and used shields that were at least partially bulletproof.[70] Frederick Coyett later described Ming lamellar armour as providing complete protection from "small arms", although this is sometimes mistranslated as "rifle bullets".[71] English literature in the early 19th century also mentions Chinese rattan shields that were "almost musket proof",[72] however another English source in the late 19th century states that they did nothing to protect their users during an advance on a Muslim stronghold, in which they were all invariably shot to death.[73]

Some were armed with bows and arrows hanging down their backs ; others had nothing save a shield on the left arm and a good sword in the right hand ; while many wielded with both hands a formidable battle-sword fixed to a stick half the length of a man. Everyone was protected over the upper part of the body with a coat of iron scales, fitting below one another like the slates of a roof; the arms and legs being left bare. This afforded complete protection from rifle bullets (mistranslation-should read "small arms") and yet left ample freedom to move, as those coats only reached down to the knees and were very flexible at all the joints. The archers formed Koxinga's best troops, and much depended on them, for even at a distance they contrived to handle their weapons with so great skill that they very nearly eclipsed the riflemen. The shield bearers were used instead of cavalry. Every tenth man of them is a leader, who takes charge of, and presses his men on, to force themselves into the ranks of the enemy. With bent heads and their bodies hidden behind the shields, they try to break through the opposing ranks with such fury and dauntless courage as if each one had still a spare body left at home. They continually press onwards, notwithstanding many are shot down ; not stopping to consider, but ever rushing forward like mad dogs, not even looking round to see whether they are followed by their comrades or not. Those with the sword-sticks—called soapknives by the Hollanders—render the same service as our lancers in preventing all breaking through of the enemy, and in this way establishing perfect order in the ranks ; but when the enemy has been thrown into disorder, the Sword-bearers follow this up with fearful massacre amongst the fugitives.[71]

— Frederick Coyett

Rocket handlers often wore heavy armour for extra protection so that they could fire at close range.[74]

Ming depiction of mail armour - it looks like scale, but this was a common artistic convention. The text says "steel wire connecting ring armour."

Ming depiction of mail armour - it looks like scale, but this was a common artistic convention. The text says "steel wire connecting ring armour." Late Southern Ming lamellar armour

Late Southern Ming lamellar armour Ming pikemen wearing brigandine

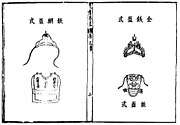

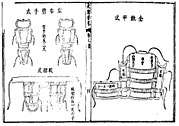

Ming pikemen wearing brigandine Ming helmet, breastplate, and mask from the Wubei Yaolue

Ming helmet, breastplate, and mask from the Wubei Yaolue Ming arm guards, thigh armour, and back plate from the Wubei Yaolue

Ming arm guards, thigh armour, and back plate from the Wubei Yaolue Ming shieldbearer

Ming shieldbearer Ming shield fence

Ming shield fence

Formations

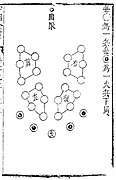

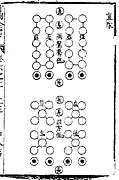

Squad level

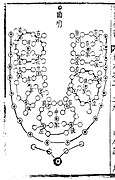

Square

Square Sharp

Sharp Crooked

Crooked Straight

Straight One

One Two

Two Qi Jiguang's 'mandarin duck formation' in standby and combat.

Qi Jiguang's 'mandarin duck formation' in standby and combat. Qi Jiguang's 'new mandarin duck formation.'

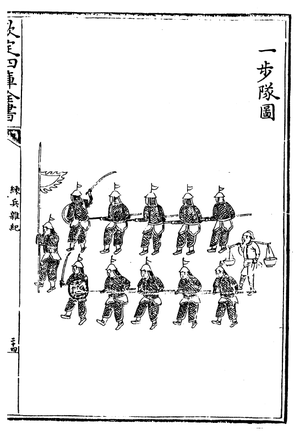

Qi Jiguang's 'new mandarin duck formation.' Qi Jiguang's 'infantry squad.' A contingent of armored soldiers.

Qi Jiguang's 'infantry squad.' A contingent of armored soldiers. Qi Jiguang's 'killer squad.' The killer squad was a reconfigured Mandarin Duck formation.

Qi Jiguang's 'killer squad.' The killer squad was a reconfigured Mandarin Duck formation. Qi Jiguang's 'firearm squad.'

Qi Jiguang's 'firearm squad.'

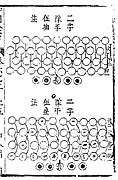

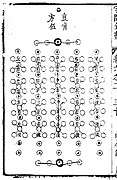

Platoon level

Square

Square Square and One

Square and One Sharp

Sharp Crooked

Crooked Straight

Straight Two

Two Two

Two Two

Two Round

Round

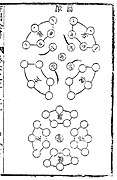

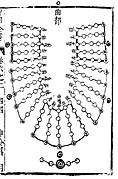

Company level

Square

Square Enemy Routing

Enemy Routing Breakout

Breakout Divide and Regroup

Divide and Regroup Crooked

Crooked Straight

Straight Straight Square

Straight Square Round

Round

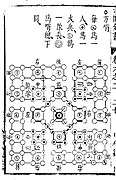

Battalion level

Square

Square Sharp

Sharp Crooked

Crooked Round

Round

Encampment level

Square

Square Square

Square Round

Round Defensive formation using carts

Defensive formation using carts

Imperial guards

Notable military figures

- Hongwu Emperor (1328-1398)

- Mu Ying (1345-1392)

- Yongle Emperor (1360-1424)

- Qi Jiguang (1528-1588)

- Yuan Chonghuan (1584-1630)

- Jiao Yu

Notes

- David M. Robinson; Dora C. Y. Ching; Chu Hung-Iam; Scarlett Jang; Joseph S. C. Lam; Julia K. Murray; Kenneth M. Swope (2008). "8". Culture, Courtiers, and Competition: The Ming Court (1368–1644) (PDF). Harvard East Asian Monographs. ISBN 0674028236. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- https://www.sav.sk/journals/uploads/040214374_Slobodn%C3%ADk.pdf p 166.

- Michael E. Haskew; Christer Joregensen (9 December 2008). Fighting Techniques of the Oriental World: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics. St. Martin's Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-312-38696-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Stephen Selby (1 January 2000). Chinese Archery. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-501-4.

- Edward L. Farmer (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. pp. 59–. ISBN 90-04-10391-0.

- Sarah Schneewind (2006). Community Schools and the State in Ming China. Stanford University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5174-2.

- http://www.san.beck.org/3-7-MingEmpire.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-12. Retrieved 2010-12-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lo Jung-pang (1 January 2012). China as a Sea Power, 1127-1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods. NUS Press. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-9971-69-505-7.

- FREDERIC WAKEMAN JR. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 25–30. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Swope 2009, p. 19.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 28.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 2.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 35-36.

- Swope 2009, p. 21.

- Swope 2009, p. 19-20.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 44–45.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 46.

- Ray Huang “Military Expenditures in Sixteenth Century Ming China.” Oriens Extremus, vol. 17, no. 1/2, (1970):39-62 pp. 43.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 58-59.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp 83.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 45.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 26-27.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 64-65.

- Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 68.

- Thomas G. Nimick, “Ch’i Chi-kuang (Qi Jiguang) and I-Wu County.” Ming Studies 34 (1995): 17-29, pp. 24.

- Thomas G. Nimick, “Ch’i Chi-kuang (Qi Jiguang) and I-Wu County.” Ming Studies 34 (1995): 17-29, pp. 25.

- Sim 2017, p. 234.

- Sim 2017, p. 236.

- Lorge 2011, p. 171.

- Jung-pang, Lo (2013). China as a Sea Power, 1127-1368. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc. pp. 331–332. ISBN 978-9971-69-505-7.

- Papelitzky 2017, p. 130.

- Papelitzky 2017, p. 132.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 54-55.

- Lorge 2011, p. 167.

- FREDERIC WAKEMAN JR. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–133, 139, 175. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 161–162, 170. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. p. 176-177. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–193, 206–208, 245. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 47.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 48.

- Peers, C.J. Soldiers of the Dragon. New York: Osprey. pp. 199–203. ISBN 1-84603-098-6.

- Dorothy Perkins (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 399–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- David M. Robinson “Military Labor in China, c. 1500.” Fighting for a Living: A Comparative Study of Military Labour 1500-2000, edited by Erik-Jan Zürcher, (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 55–56.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 379–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Swope 2009, p. 25.

- Robinson, David M. (June 2004). "Images of Subject Mongols Under the Ming Dynasty". Late Imperial China. Johns Hopkins University Press. 25 (1): 102. doi:10.1353/late.2004.0010. ISSN 1086-3257.

- Swope 2009, p. 22.

- Andrade 2016, p. 178-179.

- Hawley 2005, p. 304.

- Swope 2009, p. 341.

- Swope 2014, p. 100.

- http://ir.lis.nsysu.edu.tw:8080/bitstream/987654321/28533/1/%E5%8F%B0%E7%B2%B5%E5%85%A9%E5%9C%B0%E8%BB%8D%E8%A9%B1%E7%9A%84%E8%AA%BF%E6%9F%A5%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6.pdf

- Lorge 2011, p. 181.

- Lorge 2011, p. 177.

- Lorge 2011, p. 180.

- Zhan Ma Dao (斬馬刀), retrieved 15 April 2018

- Peers 2006, p. 203-204.

- Phillips, Gervase (1999). "Longbow and Hackbutt: Weapons Technology and Technology Transfer in Early Modern England". Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 576–593. JSTOR 25147360.

- Andrade, Tonio (2016). The Gunpowder Age China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton University Press. pp. 158, 159, 173. ISBN 9781400874446.

- Peers 2006, p. 208.

- Peers 2006, p. 185.

- ""Plate" armour of the Ming Dynasty". Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Andrade 2016, p. 57.

- Andrade 2016, p. 67.

- Swope 2009, p. 248.

- Coyet 1975, p. 51.

- Wood 1830, p. 159.

- Mesny 1896, p. 334.

- Peers 2006, p. 184.

References

- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-60391-9

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 0-304-35270-5

- Benton, Captain James G. (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2 ed.). West Point, New York: Thomas Publications. ISBN 1-57747-079-6.

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-1878-0.

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-5259-9

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82274-2.

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-718-0

- Cook, Haruko Taya (2000), Japan At War: An Oral History, Phoenix Press

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel.

- Coyet, Frederic (1975), Neglected Formosa: a translation from the Dutch of Frederic Coyett's Verwaerloosde Formosa

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79158-8.

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen.

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 0-904040-13-5.

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43519-6

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing.

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on March 25, 2004.

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650-1830, UCL Press Limited

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 23 July 2007.

- Hawley, Samuel (2005), The Imjin War, The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch/UC Berkeley Press, ISBN 89-954424-2-5

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-03718-6.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–5.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd..

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 8791114128

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29: 594–605

- May, Timothy (2012), The Mongol Conquests in World History, Reaktion Books

- McLahlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press.

- Mesny, William (1896), Mesny's Chinese Miscellany

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge At The University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, 5 pt. 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08573-X

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Ghengis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33733-0

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Papelitzky, Elke (2017), "Naval warfare of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644): A comparison between Chinese military texts and archaeological sources", in Rebecca O'Sullivan; Christina Marini; Julia Binnberg (eds.), Archaeological Approaches to Breaking Boundaries: Interaction, Integration & Division. Proceedings of the Graduate Archaeology at Oxford Conferences 2015–2016, Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, pp. 129–135.

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press.

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 0-87923-773-2

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen.

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-449-9

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000-1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Sim, Y.H. Teddy (2017), The Maritime Defense of China: Ming General Qi Jiguang and Beyond, Springer

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2009), A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598, University of Oklahoma Press

- Swope, Kenneth (2014), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, Routledge

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea Ad 612-1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-478-7

- Turnbull, Stephen (2008), The Samurai Invasion of Korea 1592-98, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, III, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32736-X

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial (2006), ISBN 0-06-093564-2

- Wilkinson, Philip (9 September 1997), Castles, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7894-2047-3

- Wilkinson-Latham, Robert (1975), Napoleon's Artillery, France: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 0-85045-247-3

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- Williams, Anthony G. (2000), Rapid Fire, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-84037-435-7

- Wood, W. W. (1830), Sketches of China