Francisco I. Madero

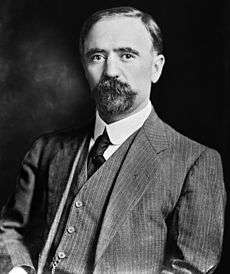

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (Spanish pronunciation: [fɾanˈsisko iɣˈnasjo maˈðeɾo ɣonˈsales]; 30 October 1873 – 22 February 1913) was a Mexican revolutionary, writer and statesman who served as the 33rd president of Mexico from 1911 until shortly before his assassination in 1913.[2][3][4][5] A wealthy landowner, he was nonetheless an advocate for social justice and democracy. Madero was notable for challenging long-time President Porfirio Díaz for the presidency in 1910 and being instrumental in sparking the Mexican Revolution.

Francisco I. Madero | |

|---|---|

Madero in 1913 | |

| 33rd President of Mexico | |

| In office 9 November 1911 – 19 February 1913 | |

| Vice President | José María Pino Suárez |

| Preceded by | Francisco León de la Barra |

| Succeeded by | Pedro Lascuráin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 October 1873 Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, Mexico |

| Died | 22 February 1913 (aged 39) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Cause of death | Assassination (gunshot wounds) |

| Resting place | Monument to the Revolution Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Progressive Constitutionalist Party[1] (previously Anti-Reelectionist Party) |

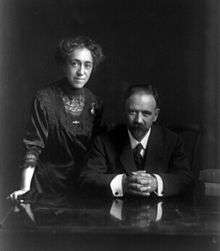

| Spouse(s) | Sara Pérez, no children |

| Relations | Brothers: Ernesto Madero Emilio Madero Gustavo A. Madero Raúl Madero Gabriel Madero |

| Parents | Francisco Indalecio Madero Hernández (father) Mercedes González Treviño (mother) |

| Residence | Coahuila |

| Alma mater | HEC Paris; University of California, Berkeley |

| Profession | Statesman, writer, revolutionary |

Born into an extremely wealthy family in the northern state of Coahuila, Madero was an unusual politician, who until he ran for president in the 1910 elections, had never held office. In his 1908 book entitled The Presidential Succession in 1910, Madero called on voters to prevent the sixth reelection of Porfirio Díaz, which Madero considered anti-democratic. His vision would lay the foundation for a democratic, twentieth-century Mexico, but without polarizing the social classes. To that effect, he bankrolled the opposition Anti-Reelectionist Party and urged voters to oust Díaz in the 1910 election. Madero's candidacy against Díaz garnered widespread support in Mexico. He was possessed of independent financial means, ideological determination, and the bravery to oppose Díaz when it was dangerous to do so.[6] Díaz had Madero arrested before the elections, which were then seen as fraudulent. Madero escaped from prison and issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí from the United States. For the first time, he called for an armed uprising against the illegitimately elected Díaz, and outlined a program of reform. The armed phase of the Mexican Revolution dates to his plan.

Uprisings in Morelos under Emiliano Zapata and in the north by Pascual Orozco, Pancho Villa and others and the inability of the Federal Army to suppress them forced Díaz's resignation on 25 May 1911, after the signing of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez; Madero was enormously popular among many sectors, but he did not assume the presidency. An interim president was installed and elections were scheduled for fall 1911. Madero was elected president on 15 October 1911 by almost 90% of the vote. Sworn into office on 6 November 1911, he became one of Mexico's youngest elected presidents, having just turned 38.

Madero's administration soon encountered opposition both from more radical revolutionaries and from conservatives. He did not move quickly on land reform, which was a key demand of many of his supporters. Former supporters Emiliano Zapata declared himself in rebellion against Madero in the Plan of Ayala as Pascual Orozco did in his Plan Orozquista. These were significant challenges to Madero's presidency. Labor also became disillusioned by his moderate policies. Foreign entrepreneurs were concerned that Madero was unable to maintain political stability that would keep their investments safe. Foreign governments were concerned that a destabilized Mexico would threaten the international order.

In February 1913, a military coup took place in the Mexican capital led by General Victoriano Huerta, the military commander of the city, and supported by the United States ambassador. Madero was arrested and a short time later assassinated along with his Vice-President, José María Pino Suárez, on 22 February 1913, following the series of events known as the Ten Tragic Days (la Decena Trágica). In death, Madero became a unifying force of disparate elements in Mexico opposed to the regime of Huerta. In the north, governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza led what became the Constitutionalist Army against Huerta, while Zapata continued in his rebellion under the Plan of Ayala. Once Huerta was ousted in July 1914, the opposition coalition held together by Madero's memory dissolved and Mexico entered a new stage of civil war.

Early years (1873–1903)

Family background

Madero was born in the hacienda of El Rosario, in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, the first son of Francisco Ignacio Madero Hernández and Mercedes González Treviño, and the first grandson of family patriarch, Evaristo Madero, governor of Coahuila. He was sickly as a child, and was small in stature as an adult.[7] It is widely believed that Madero's middle initial, I, stood for Indalecio, but according to his birth certificate it stood for Ignacio.[8] Furthermore, on the birth certificate, Ignacio was written with the archaic spelling of Ygnacio.[9]

His family has been described as one of the five wealthiest families in Mexico. His grandfather, Evaristo Madero, began as a founder of a regional carting business, but he took advantage of economic opportunity and transported cotton from the Confederate states to Mexican ports during the U.S. Civil War (1861–65). Having built a diversified fortune, but before his real success, Evaristo first married Rafaela Hernández Lombraña, half-sister of the powerful miner and banker Antonio V. Hernández. Alongside his brother-in-law, and other of his new political family's relations, he founded the Compañía Industrial de Parras, initially involved in commercial vineyards, cotton, and textiles, and later also in mining, cotton mills, ranching, banking, coal, guayule rubber, and foundries in the later part of the nineteenth century. For many years, the family prospered during Porfirio Díaz's regime, and by 1910 the family was one of the richest in Mexico, worth 30 million pesos ($15 million U.S. dollars[10] of the day, and almost $500 million U.S. dollars in today's money). Much of this wealth arose from the diversification of Madero lands during the 1890s into the production of guayule rubber plants.[11]

After the death of his first wife, and having built his success, Evaristo Madero remarried to Doña Manuela de Farías Benavides, member of one of northern Mexico's most aristocratic families, daughter of Don Juan Francisco de Farías, mayor of Laredo. Evaristo Madero also served as governor of Coahuila from 1880 to 1884,[12] during the four-year interregnum of Porfirio Díaz's rule. Afterwards, Evaristo was permanently sidelined from political office when Díaz returned to the presidency in 1884 and served until 1911. Evaristo Madero's two marriages were fruitful, with a total of 18 children, 14 of whom would survive until adulthood, and whose descendants make up some of Mexico's most influential families until this day. Thus, young Francisco was a member of a huge and powerful northern Mexican clan with a focus on commercial rather than political interests.[13]

Education

Francisco and his brother Gustavo A. Madero attended the Jesuit college in Saltillo, but his early Catholic education had little lasting impact. As a young man, his father sent him to carry out preparatory studies at the Culver Academies in the United States and later at the Lycée Hoche in Versailles, France, where he completed the classe préparatoire aux grandes écoles program. Soon after, he was admitted to study business at the prestigious École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Paris (HEC).

His father's subscription to the magazine Revue Spirite awakened in the young Madero an interest in Spiritism, an offshoot of Spiritualism. During his time in Paris, Madero made a pilgrimage to the tomb of Allan Kardec, the founder of Spiritism, and became a passionate advocate of the belief, soon coming to believe he was a medium.

Following business school, Madero traveled to the University of California, Berkeley, to study agricultural techniques and to improve his English. During his time there, he was influenced by the theosophist ideas of Annie Besant, which were prominent at nearby Stanford University.[14]

Return to Mexico

In 1893, the 20-year-old Madero returned to Mexico and assumed management of the Madero family's hacienda at San Pedro, Coahuila. Well traveled and well educated, he was now in robust health.[14] Proving an enlightened and progressive member of the Madero commercial complex,[15] Francisco installed new irrigation, introduced American cotton and cotton machinery, and built a soap factory and also an ice factory. He embarked on a lifelong commitment to philanthropy. His employees were well paid and received regular medical exams; he built schools, hospitals, and community kitchens; and he paid to support orphans and award scholarships. He also taught himself homeopathy and offered medical treatments to his employees. Francisco became increasingly engaged with Spiritism and in 1901 was convinced that the spirit of his brother Raúl, who had died at age 4, was communicating with him, urging him to do charity work and practice self-discipline and self-abnegation. Madero became a vegetarian and stopped drinking alcohol and smoking.[16]

Already well-connected to a wealthy family and now well-educated in business, he had built a personal fortune of over 500,000 pesos[15] by 1899.[14] The family was organized on patriarchal principles, so that even though young Francisco was wealthy in his own right, his father and especially his grandfather Evaristo viewed him as someone who should be under the authority of his elders. As the eldest sibling, Francisco exercised authority over his younger brothers and sisters.[17] In January 1903, he married Sara Pérez, first in a civil ceremony, and then a Catholic nuptial mass celebrated by the archbishop.[18]

Political career

Introduction to politics (1903–1908)

On 2 April 1903, Bernardo Reyes, governor of Nuevo León, violently crushed a political demonstration, an example of the increasingly authoritarian policies of president Porfirio Díaz. Madero was deeply moved and, believing himself to be receiving advice from the spirit of his late brother Raúl, he decided to act.[19] The spirit of Raúl told him, "Aspire to do good for your fellow citizens...working for a lofty ideal that will raise the moral level of society, that will succeed in liberating it from oppression, slavery, and fanaticism."[20] Madero founded the Benito Juárez Democratic Club and ran for municipal office in 1904, though he lost the election narrowly. In addition to his political activities, Madero continued his interest in Spiritualism, publishing a number of articles under the pseudonym of Arjuna (a prince from the Mahabharata).[21]

In 1905, Madero became increasingly involved in opposition to the Díaz government. He organized political clubs and founded a political newspaper (El Demócrata) and a satirical periodical (El Mosco, "The Fly"). Madero's preferred candidate, Frumencio Fuentes, was defeated by that of Porfirio Díaz in Coahuila's 1905 gubernatorial elections. Díaz considered jailing Madero, but Bernardo Reyes suggested that Francisco's father be asked to control his increasingly political son.[21]

Leader of the Anti-Re-election Movement (1908–1909)

In an interview with journalist James Creelman published in 17 February 1908 issue of Pearson's Magazine, President Díaz said that Mexico was ready for a democracy and that the 1910 presidential election would be a free election.

Madero spent the bulk of 1908 writing a book, which he believed was at the direction of spirits, now including that of Benito Juárez himself.[22] This book, published in January 1909, was titled La sucesión presidencial en 1910 (The Presidential Succession of 1910). The book quickly became a bestseller in Mexico. The book proclaimed that the concentration of absolute power in the hands of one man – Porfirio Díaz – for so long had made Mexico sick. Madero pointed out the irony that in 1871, Porfirio Díaz's political slogan had been "No Re-election". Madero acknowledged that Porfirio Díaz had brought peace and a measure of economic growth to Mexico. However, Madero argued that this was counterbalanced by the dramatic loss of freedom, including the brutal treatment of the Yaqui people, the repression of workers in Cananea, excessive concessions to the United States, and an unhealthy centralization of politics around the person of the president. Madero called for a return of the Liberal 1857 Constitution. To achieve this, Madero proposed organizing a Democratic Party under the slogan Sufragio efectivo, no reelección ("Effective Suffrage. No Re-election"). Porfirio Díaz could either run in a free election or retire.[23]

Madero's book was well received, and widely read. Many people began to call Madero the Apostle of Democracy. Madero sold off much of his property – often at a considerable loss – in order to finance anti-re-election activities throughout Mexico. He founded the Anti-Re-election Center in Mexico City in May 1909, and soon thereafter lent his backing to the periodical El Antirreeleccionista, which was run by the young lawyer/philosopher José Vasconcelos and another intellectual, Luis Cabrera Lobato.[24] In Puebla, Aquiles Serdán, from a politically engaged family, contacted Madero and as a result, formed an Anti-Re-electionist Club to organize for the 1910 elections, particularly among the working classes.[25] Madero traveled throughout Mexico giving anti-reelectionist speeches, and everywhere he went he was greeted by crowds of thousands. His candidacy cost him financially, since he sold much of his property at a loss to back his campaign.[24]

In spite of the attacks by Madero and his earlier statements to the contrary, Díaz ran for re-election. In a show of U.S. support, Díaz and William Howard Taft planned a summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, for 16 October 1909, a historic first meeting between a Mexican and a U.S. president and also the first time a U.S. president would cross the border into Mexico.[26] At the meeting, Diaz told John Hays Hammond, "Since I am responsible for bringing several billion dollars in foreign investments into my country, I think I should continue in my position until a competent successor is found."[27] The summit was a great success for Díaz, but it could have been a major tragedy. On the day of the summit, Frederick Russell Burnham, the celebrated scout, and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol along the procession route and they disarmed the assassin within only a few feet of Díaz and Taft.[26]

The Porfirian regime reacted to Madero by placing pressure on the Madero family's banking interests, and at one point even issued a warrant for Madero's arrest on the grounds of "unlawful transaction in rubber".[28] Madero was not arrested, though, apparently due in part to the intervention of Díaz's finance minister, José Yves Limantour, a friend of the Madero family.[29] In April 1910, the Anti-Re-electionist Party met and selected Madero as their nominee for President of Mexico.

During the convention, a meeting between Madero and Díaz was arranged by the governor of Veracruz, Teodoro Dehesa, and took place in Díaz's residence on 16 April 1910. Only the candidate and the president were present for the meeting, so the only account of it is Madero's own in correspondence. A political solution and compromise might have been possible, with Madero withdrawing his candidacy.[30] It became clear to Madero that Díaz was a decrepit old man, out of touch politically, and unaware of the extent of formal political opposition.[30] The meeting was important for strengthening Madero's resolve that political compromise was not possible and he is quoted as saying "Porfirio is not an imposing chief. Nevertheless, it will be necessary to start a revolution to overthrow him. But who will crush it afterwards?"[31] Madero was worried that Porfirio Díaz would not willingly relinquish office, warned his supporters of the possibility of electoral fraud and proclaimed that "Force shall be met by force!"[32]

Campaign, arrest, escape 1910

Madero campaigned across the country on a message of reform and met with numerous supporters. Resentful of the "peaceful invasion" from the United States "which came to control 90 percent of Mexico's mineral resources, its national railroad, its oil industry and, increasingly, its land," Mexico's poor and middle-class overwhelmingly showed their support for Madero.[33] Fearful of a dramatic change in direction, on 6 June 1910, the Porfirian regime arrested Madero in Monterrey and sent him to a prison in San Luis Potosí. Approximately 5,000 other members of the Anti-Re-electionist movement were also jailed. Francisco Vázquez Gómez took over the nomination, but during Madero's time in jail, a fraudulent election was held on 21 June 1910 that gave Díaz an unbelievably large margin of victory.

Madero's father used his influence with the state governor and posted bond to give Madero the right to move about the city on horseback during the day. On 4th October 1910, Madero galloped away from his guards and took refuge with sympathizers in a nearby village. Three days later he was smuggled across the U.S. border, hidden in a baggage car by sympathetic railway workers.

Plan of San Luis Potosí and rebellion

_Pascual_Orozco._(21879503251).jpg)

Madero set up shop in San Antonio, Texas, and quickly issued his Plan of San Luis Potosí, which had been written during his time in prison, partly with the help of Ramón López Velarde. The plan proclaimed the elections of 1910 null and void, and called for an armed revolution to begin at 6 pm on 20 November 1910, against the "illegitimate presidency/dictatorship of Díaz". At that point, Madero declared himself provisional President of Mexico, and called for a general refusal to acknowledge the central government, restitution of land to villages and Indian communities, and freedom for political prisoners. Madero's policies painted him as a leader of each of the different castes in Mexican society at the time. He was a member of the upper class; the middle class saw that he sought to gain entry into political processes; the lower class saw that he promised fairer politics and a much more substantial, equitable economic system.[34]

The family drew on its financial resources to make regime change possible, with Madero's brother Gustavo A. Madero hiring the law firm of Washington lawyer Sherburne Hopkins, the "world's best rigger of Latin American revolutions" to foment support in the U.S.[35] A strategy to discredit Díaz with U.S. business and the U.S. government did meet some success, with Standard Oil engaging in talks with Gustavo Madero, but more importantly, the U.S. government "bent neutrality laws for the revolutionaries."[36] The U.S. Senate held hearings in 1913 as to whether the U.S. had any role in fomenting revolution in Mexico,[37] Hopkins gave testimony that "he did not believe that it cost the Maderos themselves more than $400,000 gold", with the aggregate cost being $1,500,000US.[38]

On 20 November 1910, Madero arrived at the border and planned to meet up with 400 men raised by his uncle Catarino to launch an attack on Ciudad Porfirio Díaz (modern-day Piedras Negras, Coahuila). However, his uncle arrived late and brought only ten men. Madero decided to postpone the revolution. Instead, he and his brother Raúl (who had been given the same name as his late brother) traveled incognito to New Orleans, Louisiana.

On 14 February 1911, Madero crossed the border into Chihuahua state from Texas, and on 6 March 1911 led 130 men in an attack on Casas Grandes, Chihuahua. Madero was reported wounded in the fighting, but was saved by his personal bodyguard and Revolutionary general Máximo Castillo.[39] He spent the next several months as the head of the Mexican Revolution. Madero successfully imported arms from the United States, with the American government under William Howard Taft doing little to halt the flow of arms to the Mexican revolutionaries. By April the Revolution had spread to eighteen states, including Morelos where the leader was Emiliano Zapata.

On 1 April 1911, Porfirio Díaz claimed that he had heard the voice of the people of Mexico, replaced his cabinet, and agreed to restitution of the lands of the dispossessed. Madero did not believe this statement and instead demanded the resignation of President Díaz and Vice-President Ramón Corral. Madero then attended a meeting with the other revolutionary leaders – they agreed to a fourteen-point plan which called for pay for revolutionary soldiers; the release of political prisoners; and the right of the revolutionaries to name several members of cabinet. Madero was moderate, however. He believed that the revolutionaries should proceed cautiously so as to minimize bloodshed and should strike a deal with Díaz if possible. In early May, Madero wanted to extend a ceasefire, but his fellow revolutionaries Pascual Orozco and Francisco Villa disagreed and went ahead without orders on 8 May to attack Ciudad Juárez, which surrendered after two days of bloody fighting. The revolutionaries won this battle decisively, making it clear that Díaz could no longer retain power. On 21 May 1911, the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez was signed.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, Díaz and Corral agreed to resign by the end of May 1911, with Díaz's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Francisco León de la Barra, becoming interim president solely for the purpose of calling general elections.

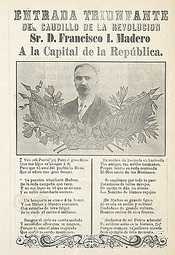

This first phase of the Mexican Revolution thus ended with Díaz leaving for exile in Europe at the end of May 1911, escorted into exile by General Victoriano Huerta. On 7 June 1911, Madero entered Mexico City in triumph where he was greeted with huge crowds shouting "¡Viva Madero!"

Interim Presidency of De la Barra (May–November 1911)

Although Madero and his supporters had forced Porfirio Díaz from power, he did not assume the presidency in June 1911. Instead, following the terms of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, he was a candidate for president and had no formal role in the Interim Presidency of Francisco León de la Barra, a diplomat and lawyer. Left in place was the Congress of Mexico, which was full of candidates whom Díaz had handpicked for the 1910 election. By doing this, Madero was true to his ideological commitment to constitutional democracy, but with members of the Díaz regime still in power, he was caused difficulties in the short and long term. The German ambassador to Mexico, Paul von Hintze, who associated with the Interim President, said of him that "De la Barra wants to accommodate himself with dignity to the inevitable advance of the ex-revolutionary influence, while accelerating the widespread collapse of the Madero party...."[40] Madero sought to be a moderate democrat and follow the course outlined in treaty bringing about exile of Díaz, but by calling for the disarming and demobilization of his revolutionary base, he undermined his support. The Mexican Federal Army, just defeated by the revolutionaries, was to continue as the armed force of the Mexican state. Madero argued that the revolutionaries should henceforth proceed solely by peaceful means. In the south, revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata was skeptical about disbanding his troops, especially since the Federal Army from the Díaz era remained essentially intact. However, Madero traveled south to meet with Zapata at Cuernavaca and Cuautla, Morelos. Madero assured Zapata that the land redistribution promised in the Plan of San Luis Potosí would be carried out when Madero became president.

With Madero now campaigning for the presidency, which he was expected to win, several landowners from Zapata's state of Morelos took advantage of his not being head of state and appealed to President De la Barra and the Congress to restore their lands which had been seized by Zapatista revolutionaries. They spread exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by Zapata's irregulars, calling Zapata the "Attila of the South". De la Barra and the Congress, therefore, decided to send regular troops under Victoriano Huerta to suppress Zapata's revolutionaries. Madero once again traveled south to urge Zapata to disband his supporters peacefully, but Zapata refused on the grounds that Huerta's troops were advancing on Yautepec. Zapata's suspicions proved accurate as Huerta's Federal soldiers moved violently into Yautepec. Madero wrote to De la Barra, saying that Huerta's actions were unjustified and recommending that Zapata's demands be met. However, when he left the south, he had achieved nothing. Nevertheless, he promised the Zapatistas that once he became president, things would change. Most Zapatistas had grown suspicious of Madero, however.

Madero presidency (November 1911 – February 1913)

Madero became president in November 1911, and, intending to reconcile the nation, appointed a cabinet which included many of Porfirio Díaz's supporters. A curious fact is that almost immediately after taking office in November, Madero became the first head of state in the world to fly in an airplane, which the Mexican press was later to mock.[41] Madero was unable to achieve the reconciliation he desired since conservative Porfirians had organized themselves during the interim presidency and now mounted a sustained and effective opposition to Madero's reform program. Conservatives in the Senate refused to pass the reforms he advocated. At the same time, several of Madero's allies denounced him for being overly conciliatory with the Porfirians and with not moving aggressively forward with reforms.

After years of censorship, Mexican newspapers took advantage of their newly found freedom of the press to harshly criticize Madero's performance as president. Gustavo A. Madero, the president's brother, remarked that "the newspapers bite the hand that took off their muzzle." President Madero refused the recommendation of some of his advisors that he bring back censorship. The press was particularly critical of Madero's handling of rebellions that broke out against his rule shortly after he became president.

Despite internal and external opposition, the Madero administration had a number of important accomplishments, including freedom of the press. He freed political prisoners and abolished the death penalty. He did away with the practice of the Díaz government, which appointed local political bosses (jefes políticos), and instead set up a system of independent municipal authorities. State elections were free and fair. He was concerned about the improvement of education, establishing new schools and workshops. An important step was the creation of a federal department of labor, limited the workday to 10 hours, and set in place regulations on women's and children's labor. Unions were granted the right to freely organize. The Casa del Obrero Mundial ("House of the World Worker"), an organization with anarcho-syndicalist was founded during his presidency.[42]

Madero alienated a number of his political supporters when he created a new political party, the Constitutionalist Progressive party, which replaced the Anti-Reelectionist Party. He ousted leftist Emilio Vázquez Gómez from his cabinet, brother of Francisco Vázquez Gómez, whom Madero had replaced as his vice presidential candidate with Pino Suárez.[43]

Rebellions

Madero retained the Mexican Federal Army and ordered the demobilization of revolutionary forces. For revolutionaries who considered themselves the reason that Díaz resigned, this was a hard course to follow. Since Madero did not implement immediate, radical reforms that many of those had supported him had expected, he lost control of those areas in Morelos and Chihuahua. A series of internal rebellions challenged Madero's presidency before the February 1913 coup that deposed him.

Zapatista rebellion

In Morelos, Emiliano Zapata proclaimed the Plan of Ayala on 25 November 1911, which excoriated Madero's slowness on land reform. Zapata's plan recognized Pascual Orozco as fellow revolutionary, although Orozco was for the moment loyal to Madero, until 1912.

Reyes rebellion

In December 1911, Bernardo Reyes (the popular general whom Porfirio Díaz had sent to Europe on a diplomatic mission because Díaz worried that Reyes was going to challenge him for the presidency) launched a rebellion in Nuevo León, where he had previously served as governor. Reyes's rebellion lasted only eleven days before Reyes surrendered at Linares, Nuevo León, and was sent to the Santiago Tlatelolco prison in Mexico City.

Orozco rebellion

In March 1912, Madero's former general Pascual Orozco, who was personally resentful of how President Madero had treated him once he was in office, launched a rebellion in Chihuahua with the financial backing of Luis Terrazas, a former Governor of Chihuahua who was the largest landowner in Mexico. Madero dispatched troops under General José González Salas to put down the rebellion, but they were initially defeated by Orozco's troops. González Salas committed suicide and General Victoriano Huerta assumed control of the federalist forces. Huerta was more successful, defeating Orozco's troops in three major battles and forcing Orozco to flee to the United States in September 1912.

Relations between Huerta and Madero grew strained during the course of this campaign when Pancho Villa, the commander of the División del Norte, refused orders from General Huerta. Huerta ordered Villa's execution, but Madero commuted the sentence and Villa was sent to the same Santiago Tlatelolco prison as Reyes from which he escaped on Christmas Day 1912.[44] Angry at Madero's commutation of Villa's sentence, Huerta, after a long night of drinking, mused about reaching an agreement with Orozco and together deposing Madero as president. When Mexico's Minister of War learned of General Huerta's comments, he stripped Huerta of his command, but Madero intervened and restored Huerta to command.

Félix Díaz rebellion

October 1912, Félix Díaz (nephew of Porfirio Díaz) launched a rebellion in Veracruz, "to reclaim the honor of the army trampled by Madero." This rebellion was quickly crushed and Félix Díaz was imprisoned. Madero was prepared to have Félix Díaz executed, but the Supreme Court of Mexico declared that Félix Díaz would be imprisoned, but not executed.

Ten Tragic Days and death of Madero

In early 1913, General Félix Díaz (Porfirio Díaz's nephew) and General Bernardo Reyes plotted the overthrow of Madero, with the support of US Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson. Now known in Mexican history as the Ten Tragic Days, from 9 February to 19 February events in the capital led to the overthrow and murder of Madero and his vice president. Rebel forces bombarded the National Palace and downtown Mexico City from the military arsenal (ciudadela). Madero's loyalists initially held their ground, but Madero's commander, General Victoriano Huerta secretly switched sides to support the rebels. Madero's decision to appoint General Victoriano Huerta as commander of forces in Mexico City was one "for which he would pay for with his life."[46] Madero and his vice president were arrested. Under pressure Madero resigned the presidency, with the expectation that he would go into exile, as had President Díaz in May 1911. Madero's brother and advisor Gustavo A. Madero was kidnapped off the street, tortured, and killed. Following Huerta's coup d'état on 18 February 1913, Madero was forced to resign. After a 45-minute term of office, Pedro Lascuráin was replaced by Huerta, who took over the presidency later that day.[47]

Following his forced resignation, Madero and his Vice-President José María Pino Suárez were kept under guard in the National Palace. On the evening of 22 February, they were told that they were to be transferred to the main city penitentiary, where they would be safer. At 11:15 pm, reporters waiting outside the National Palace saw two cars containing Madero and Suárez emerge from the main gate under a heavy escort commanded by Major Francisco Cárdenas, an officer of the rurales.[48] The journalists on foot were outdistanced by the motor vehicles, which were driven towards the penitentiary. The correspondent for the New York World was approaching the prison when he heard a volley of shots. Behind the building, he found the two cars with the bodies of Madero and Suárez nearby, surrounded by soldiers and gendarmes. Major Cárdenas subsequently told reporters that the cars and their escort had been fired on by a group, as they neared the penitentiary. The two prisoners had leapt from the vehicles and ran towards their presumed rescuers. They had however been killed in the cross-fire.[49] This account was treated with general disbelief, although the American ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, a strong supporter of Huerta, reported to Washington that, "I am disposed to accept the (Huerta) government's version of the affair and consider it a closed incident".[50]

President Madero, dead at 39, was buried quietly in the French cemetery of Mexico City. A series of contemporary photographs taken by Manuel Ramos show Maderos's coffin being carried from the penitentiary and placed on a special funeral tram car for transportation to the cemetery.[51] Only his close family were permitted to attend, leaving for Cuba immediately after. Ambassador Wilson was later dismissed from his position after US president Woodrow Wilson took office. Following Huerta's overthrow, Francisco Cárdenas fled to Guatemala where he committed suicide in 1920 after the new Mexican government had requested his extradition to stand trial for the murder of Madero.[52][53]

Aftermath of coup

There was shock at Madero's murder, but there were many, Mexican elites and foreign entrepreneurs and governments, who saw the coup and the emergence of Victoriano Huerta as the desired strongman to return order to Mexico. Among elites in Mexico, Madero's death was a cause of rejoicing, seeing the time since Díaz's resignation as one of political instability and economic uncertainty. Ordinary Mexicans in the capital, however, were dismayed by the coup, since many considered Madero a friend, but their feelings did not translate into concrete action against the Huerta regime.[54] In northern Mexico, Madero's overthrow and martyrdom united forces against Huerta's usurpation of power. Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza refused to support the new regime although most state governors had. He brought together a coalition of revolutionaries under the banner of the Mexican Constitution, so that the Constitutionalist Army fought for the principles of constitutional democracry that Madero embraced. In southern Mexico, Zapata had been in rebellion against the Madero government for its slow action on land reform and continued in rebellion against the Huerta regime. However, Zapata repudiated his former high opinion of fellow revolutionary Pascual Orozco, who had also rebelled against Madero, when Orozco allied with Huerta. Madero's anti-reelectionist movement had mobilized revolutionary action that led to the resignation of Díaz. Madero's overthrow and murder during the Ten Tragic Days was a prelude to further years of civil war.

Historical memory and popular culture

Madero was known as "The Apostle of Democracy," but "Madero the martyr meant more to the soul of Mexico."[55]

Despite Madero's importance as a historical figure, there are relatively few memorials or monuments to him. It was not until the Monument to the Revolution was completed in 1938 that Madero had a public resting place. He had been interred in the French cemetery in Mexico City. After his death. His tomb had been an informal pilgrimage site on the anniversary of his murder (February 22) and the proclamation of his Plan of San Luis Potosí (November 20), which launched the Mexican Revolution.[56] Initially, the monument to the Revolution held the remains of Madero, Carranza, and Villa and was planned as a collective commemoration of the Revolution, not individual revolutionaries. Although it was completed on 20 November 1938, there was no inaugural ceremony.[57]

The date of Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí, November 20, was a fixed official holiday in Mexico, Revolution Day, but a 2005 change in the law makes the third Monday in November the day of commemoration. During the Presidency of Venustiano Carranza, he ignored November 20 and commemorated March 26, the anniversary of his Plan de Guadalupe.[58]

The Mexico City Metro has a stop named for Madero's vice president, Metro Pino Suárez, but not one to Madero. General Alvaro Obregón laid a foundation stone on the 10th anniversary of Madero's death of a planned Madero statue in the zócalo, but the statue was never built. A statue was erected in 1956 at a downtown intersection in Mexico City and has been moved to the presidential residence, Los Pinos, not easily viewable by the public.[59] An exception is Avenida Madero in Mexico City. One contemporaneous honor by General Pancho Villa remains in Mexico City. On the morning of 8 December 1914, he declared that the street leading from the Zócalo in Mexico City towards the Paseo de la Reforma would be named for Madero. Still officially called Francisco I. Madero Avenue, but commonly known simply as Madero street, it is one of the most popular and historically significant streets in the city. It was pedestrianised in 2009.

Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada created an etching for a broadside,[60] produced on the occasion of Madero's election in 1910, titled "Calavera de Madero" portraying Madero as a calavera.

Madero appears in the films Viva Villa! (1934), Villa Rides (1968) and Viva Zapata! (1952).

In the novel The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996) by James Carlos Blake, Madero is a major character.

See also

References

- Anti-Reelectionist-Progressive Constitutional Archived 4 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Krauze, p. 250

- Flores Rangel, Juan José. Historia de Mexico 2, p. 86. Cengage Learning Editores, 2003, ISBN 970-686-185-8

- Schneider, Ronald M. Latin American Political History, p. 168. Westview Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8133-4341-0

- "Francisco I. Madero – 38° Presidente de México". presidentes.mx. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Cumberland, Charles C. Mexican Revolution: Genesis Under Madero. Austin: University of Texas Press 1952, p. 70.

- Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997, pp. 245–46.

- Administrator. "Revolución / Francisco I. Madero: con "I" de Ignacio, por Alejandro Rosas". www.bicentenario.gob.mx. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Madero era (Y)gnacio, no Indalecio". Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Ross, Stanley R. Francisco I. Madero, Apostle of Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press 1955, 3.

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution Volume 1. Porfirians, Liberals and Peasants. p. 110. ISBN 0-8032-7770-9.

- Ross, Francisco I. Madero, p. 4.

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution Volume 1. Porfirians, Liberals and Peasants. p. 55. ISBN 0-8032-7770-9.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 247.

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution Volume 1. Porfirians, Liberals and Peasants. p. 56. ISBN 0-8032-7770-9.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 248.

- Ross, Francisco I. Madero, pp. 15–16.

- Ross, Francisco I. Madero, p. 17.

- Madero had another brother, also named Raúl, who survived to adulthood and participated in the Mexican Revolution. Ross, Madero, p. 15.

- quoted in Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, pp. 248, and 820, footnote 10 who cites a Madero manuscript in a private collection.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 249.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, pp. 251–253.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, pp. 252–253.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 253.

- LaFrance, David G. "Aquiles Serdán" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2, p. 1341. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2009). The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906–1920. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 1–17, 213. ISBN 978-0-8263-4652-0.

- López Obrador, Andrés Manuel (2014). Neoporfirismo: Hoy como ayer. Berkeley, CA: Grijalbo. ISBN 9786073123266.

- Ross, Francisco I. Madero, pp. 96–97.

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 254.

- Ross, Francisco I. Madero, p. 100.

- quoted in Ross, Francisco I. Madero, p. 100.

- quoted in Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 254.

- Zeit, Joshua (4 February 2017). "The Last Time the U.S. Invaded Mexico". Politico Magazine. Washington, D.C.: Politico. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Wasserman, Mark (2012). The Mexican Revolution: A Brief History with Documents. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-312-53504-9.

- Womack, John Jr. "The Mexican Revolution" in Mexico Since Independence. Leslie Bethell, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, p. 130.

- Womack, "The Mexican Revolution", p. 131.

- Calvert, Peter. The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1914: The Diplomacy of Anglo-American Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968, p. 77 citing United States, Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations: Revolutions in Mexico, United States Senate, Sixty-Second Congress, Second Session pursuant to S. Res. 335...

- Calvert, The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1914, p. 77.

- Castillo, Máximo (2016). Valdés, Jesús Vargas (ed.). Máximo Castillo and the Mexican Revolution. Translated by Aliaga-Buchenau, Ana-Isabel. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0807163887.

- quoted in Friedrich Katz, The Secret War in Mexico. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1981, pp. 40-41.

- "Did You Know? The World's first aerial bombing: the Battle of Topolobampo, Mexico : Mexico History". www.mexconnect.com. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Tortolero Cervantes,. "Francisco I. Madero" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 766-67.

- LaFrance, David. "Francisco I. Madero" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996, p. 488.

- Heribert von Feilitzsch, In Plain Sight: Felix A. Sommerfeld, Spymaster in Mexico, 1908 to 1914, Henselstone Verlag LLC, 2012, p. 212

- Album, Mexican Revolution

- Katz, The Secret War in Mexico, p. 96.

- Krauze, Enrique. Madero Vivo. Mexico City: Clio, pp. 119-21

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution. Volume 1. Porfirians, Liberals and Peasants. p. 489. ISBN 0-8032-7770-9.

- Aitken, Ronald. Revolution! Mexico 1910–20, pp. 142–143, 586 03669 5

- Aitken, Ronald. Revolution! Mexico 1910–20, page 144, 586 03669 5

- "President Madero's coffin being placed in funeral car, Mexico City :: Mexico – Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints". digitalcollections.smu.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Aitken, Ronald. Revolution! Mexico 1910–20, p. 144, 586 03669 5

- Montes Ayala, Francisco Gabriel (1993). Raúl Oseguera Pérez, ed. "Francisco Cárdenas. Un hombre que cambió la history". Sahuayo, Michoacán: Impresos ABC.

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986, pp. 1-2.

- quoted in Benjamin, Thomas. La Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History. Austin: University of Texas Press 2000, p. 50

- Benjamin, La Revolución, p. 124

- Benjamin, La Revolución, pp. 131-32.

- Benjamin, La Revolución, p. 59

- Benjamin, La Revolución pp. 124, 195

- "C50 Calavera de D. Francisco I. Madero". www.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

Further reading

- Caballero, Raymond (2017). Orozco: Life and Death of a Mexican Revolutionary. Chichago: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Caballero, Raymond (2015). Lynching Pascual Orozco, Mexican Revolutionary Hero and Paradox. Create Space. ISBN 978-1514382509.

- Cumberland, Charles C. Mexican Revolution: Genesis under Madero. Austin: University of Texas Press 1952.

- Katz, Friedrich. The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1981.

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution, 2 volumes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986.

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Ross, Stanley R. Francisco I. Madero, Apostle of Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press 1955.

External links

- Works by or about Francisco I. Madero in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Francisco León de la Barra |

President of Mexico 6 November 1911 – 19 February 1913 |

Succeeded by Pedro Lascuráin |