Mesopotamian Arabic

Mesopotamian Arabic, also known as South Mesopotamian Arabic and Iraqi Arabic, is a continuum of mutually-intelligible varieties of Arabic native to the Mesopotamian basin of Iraq as well as spanning into Syria,[3] Iran,[3] southeastern Turkey,[4] and spoken in Iraqi diaspora communities.

| Mesopotamian Arabic | |

|---|---|

| Iraqi Arabic | |

| اللهجة العراقية | |

| Native to | Iraq (Mesopotamia), Syria, Turkey, Iran, Kuwait, Jordan, parts of northern and eastern Arabia |

| Region | Mesopotamia, Armenian Highlands, Cilicia |

Native speakers | About 25.7 million speakers (2014-2016)[1] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

| Dialects | |

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:acm – Mesopotamian Arabicayp – North Mesopotamian Arabic |

| Glottolog | meso1252[2] |

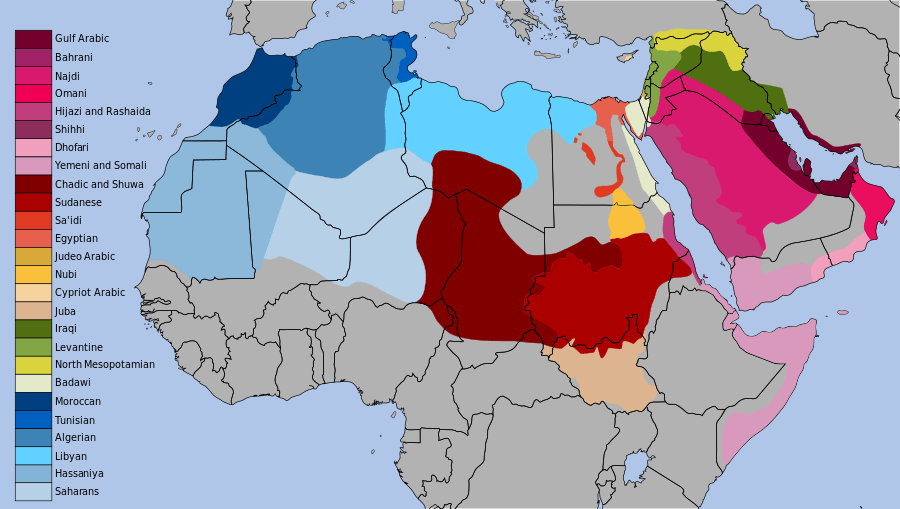

Khaki: Iraqi Arabic | |

Mesopotamian Arabic has an Aramaic Syriac substrate, and also shares significant influences from ancient Mesopotamian languages of Akkadian, Sumerian and Babylonian, as well as Persian, Turkish, Kurdish and Greek. Mesopotamian Arabic is said to be the most Aramaic-Syriac influenced dialect of Arabic, due to Aramaic-Syriac having originated in Mesopotamia, and spread throughout the Middle East (Fertile Crescent) during the Neo-Assyrian period, eventually becoming the lingua franca of the entire region before Islam.[5][6][7] Iraqi Arabs and Assyrians are the largest Semitic peoples in Iraq, sharing significant similarities in language between Mesopotamian Arabic and Syriac.

History

Aramaic was the lingua franca in Mesopotamia from the early 1st millennium BCE until the late 1st millennium CE, and as may be expected, Iraqi Arabic shows signs of an Aramaic substrate.[8] The Gelet and the Judeo-Iraqi varieties have retained features of Babylonian Aramaic.[8]

Due to Iraq's inherent multiculturalism as well as history, Iraqi Arabic in turn bears extensive borrowings in its lexicon from Aramaic, Akkadian, Persian, Turkish, the Kurdish languages and Hindustani. The inclusion of Mongolian and other Turkic elements in the Iraqi Arabic dialect should also be mentioned, because of the political role a succession of Turco-Mongol dynasties played after Mesopotamia was invaded by Mongol-Turkic colonizers in 1258 that made Iraq became part of Ilkhanate (Iraq is the only Arab country that was influenced by Mongols), and also because of the prestige Iraqi Arabic dialect and literature enjoyed in the part of Arab world, which was often ruled by sultans and emirs with a Turkic background.

Phonology

Vowels

Consonants

Even in the most formal of conventions, pronunciation depends upon a speaker's background.[9] Nevertheless, the number and phonetic character of most of the consonants has a broad degree of regularity among Arabic-speaking regions. Note that Arabic is particularly rich in uvular, pharyngeal, and pharyngealized ("emphatic") sounds. The emphatic coronals (/sˤ/, /tˤ/, and /ðˤ/) cause assimilation of emphasis to adjacent non-emphatic coronal consonants. The phonemes /p/ ⟨پ⟩ and /v/ ⟨ڤ⟩ (not used by all speakers) are not considered to be part of the phonemic inventory, as they exist only in foreign words and they can be pronounced as /b/ ⟨ب⟩ and /f/ ⟨ف⟩ respectively depending on the speaker.

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic1 | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | (p) | t | tˤ | t͡ʃ | k | q | ʔ | ||

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | g | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x ~ χ | ħ | h | |

| voiced | (v) | ð | z | ðˤ | ɣ ~ ʁ | ʕ | ||||

| Trill | r | ʜ[10] | ||||||||

| Tap | ɾ | ʡ̆[10] | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | (ɫ) | j | w | ||||||

Phonetic notes:

- /p/ and /v/ occur mostly in borrowings from Persian, and may be assimilated to /b/ or /f/ in some speakers.

- Original /q/ splits lexically into /q/ and /ɡ/ in most dialects, but /ɡ/ is pronounced in southern Mesopotamian dialects, even in Modern Standard Arabic.

- The gemination of the flap /ɾ/ results in a trill /r/.

Varieties

Mesopotamian Arabic has two major varieties. A distinction is recognised between Gelet Mesopotamian Arabic and Qeltu Mesopotamian Arabic, the names deriving from the form of the word for "I said".[11]

The southern (Gelet) group includes a Tigris dialect cluster, of which the best-known form is Baghdadi Arabic, and a Euphrates dialect cluster, known as Furati (Euphrates Arabic). The Gelet variety is also spoken in the Khuzestan Province of Iran.[3]

The northern (Qeltu) group includes the north Tigris dialect cluster, also known as North Mesopotamian Arabic or Maslawi (Mosul Arabic), as well as both Jewish and Christian sectarian dialects (such as Baghdad Jewish Arabic).

Distribution

Both the Gelet and the Qeltu varieties of Iraqi Arabic are spoken in Syria,[3][4] the former is spoken on the Euphrates east of Aleppo and in Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, Khuzestan Province, Iran and across the border in Turkey.[4]

Cypriot Arabic shares a large number of common features with Mesopotamian Arabic;[12] particularly the northern variety, and has been reckoned as belonging to this dialect area.[13]

See also

- Varieties of Arabic

- North Mesopotamian Arabic

- Baghdad Arabic

References

- "Arabic, Mesopotamian Spoken - Ethnologue". Ethnologue. Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2017. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twentieth edition. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Gilit Mesopotamian Arabic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Arabic, Mesopotamian | Ethnologue

- Arabic, North Mesopotamian | Ethnologue

- Aramaic was the medium of everyday writing, and it provided scripts for writing. (1997). Humanism, Culture, and Language in the Near East : Studies in Honor of Georg Krotkoff. Krotkoff, Georg., Afsaruddin, Asma, 1958-, Zahniser, A. H. Mathias, 1938-. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575065083. OCLC 747412055.

- Tradition and modernity in Arabic language and literature. Smart, J. R., Shaban Memorial Conference (2nd : 1994 : University of Exeter). Richmond, Surrey, U.K. p. 253. ISBN 9781136788123. OCLC 865579151.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Sanchez, Francisco del Rio. ""Influences of Aramaic on dialectal Arabic", in: Archaism and Innovation in the Semitic Languages. Selected papers". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Muller-Kessler, Christa (July–September 2003). "Aramaic 'K', Lyk' and Iraqi Arabic 'Aku, Maku: The Mesopotamian Particles of Existence". The Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (3): 641–646. doi:10.2307/3217756. JSTOR 3217756.

- Holes (2004:58)

- John H. Elsing, The Articulatory Function of the Larynx and the Origins of Speech, University of Victoria, 2012, p. 126.

- Mitchell, T. F. (1990). Pronouncing Arabic, Volume 2. Clarendon Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-19-823989-0.

- Versteegh, Kees (2001). The Arabic Language. Edinburgh University Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-7486-1436-2.

- Owens, Jonathan (2006). A Linguistic History of Arabic. Oxford University Press. p. 274. ISBN 0-19-929082-2.

| Mesopotamian Arabic test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |