Hejazi Arabic

Hejazi Arabic or Hijazi Arabic (Arabic: حجازي, romanized: ḥijāzī), also known as West Arabian Arabic, is a variety of Arabic spoken in the Hejaz region in Saudi Arabia. Strictly speaking, there are two main groups of dialects spoken in the Hejaz region,[3] one by the urban population, originally spoken mainly in the cities of Jeddah, Mecca and Medina and another by the urbanized rural and bedouin populations.[4]. However, the term most often applies to the urban variety which is discussed in this article.

| Hejazi Arabic | |

|---|---|

| Hijazi Arabic West Arabian Arabic | |

| حجازي Ḥijāzi | |

| Pronunciation | [ħɪˈdʒaːzi], [ħe̞ˈdʒaːzi] |

| Native to | Hejaz region, Saudi Arabia |

Native speakers | 14.5 million (2011)[1] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early form | Old Hejazi

|

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | acw |

| Glottolog | hija1235[2] |

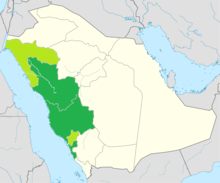

regions where Hejazi is the dialect of the majority regions considered as part of modern Hejaz region | |

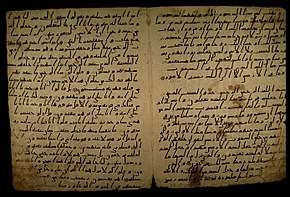

In antiquity, the Hejaz was home to the Old Hejazi dialect of Arabic recorded in the consonantal text of the Qur'an. Old Hejazi is distinct from modern Hejazi Arabic, and represents an older linguistic layer wiped out by centuries of migration, but which happens to share the imperative prefix vowel /a-/ with the modern dialect.

Classification

Hejazi Arabic belongs to the western Peninsular Arabic branch of the Arabic language, which itself is a Semitic language. It includes features of both urban and bedouin dialects given its history between the ancient urban cities of Medina and Mecca and the bedouin tribes that lived on the outskirts of these cities.

Features

Also referred to as the sedentary Hejazi dialect, this is the form most commonly associated with the term "Hejazi Arabic", and is spoken in the urban centers of the region, such as Jeddah, Mecca, and Medina. With respect to the axis of bedouin versus sedentary dialects of the Arabic language, this dialect group exhibits features of both. Like other sedentary dialects, the urban Hejazi dialect is less conservative than the bedouin varieties in some aspects and has therefore shed some Classical forms and features that are still present in bedouin dialects, these include gender-number disagreement, and the feminine marker -n (see Varieties of Arabic). But in contrast to bedouin dialects, the constant use of full vowels and the absence of vowel reduction plus the distinction between the emphatic letters ⟨ض⟩ and ⟨ظ⟩ is generally retained.

Innovative features

- The present progressive tense is marked by the prefix بـ /bi/ or قاعد /gaːʕid/ as in بيدرس /bijidrus/ or قاعد يدرس /gaːʕid jidrus/ ("he is studying").

- The future tense is marked by the prefix حـ /ħa/ or راح /raːħ/ as in حيدرس /ħajidrus/ or راح يدرس /raːħ jirdrus/ ("he is going to study").

- the internal passive form, which in Hejazi, is replaced by the pattern (أنفعل /anfaʕal/, ينفعل /jinfaʕil/) or (أتْفَعَل /atfaʕal/, يتفعل /jitfaʕil/).[5]

- The final -n in present tense plural verb forms is no longer employed (e.g. يركبوا /jirkabu/ instead of يركبون /jarkabuːn/).

- The dominant case ending before the 3rd person masculine singular pronoun is -u, rather than the -a that is prevalent in bedouin dialects. For example, بيته /beːtu/ ("his house"), عنده /ʕindu/ ("he has"), أعرفه /aʕrifu/ ("I know him").

- All numbers have no gender except for the number "one" which is واحد m. /waːħid/ and وحدة f. /waħda/.

- The pronunciation of the interdental letters ⟨ث⟩ ,⟨ذ⟩, and ⟨ظ⟩. (See Hejazi Arabic Phonology)

Conservative features

- Hejazi Arabic does not employ double negation, nor does it append the negation particles -sh to negate verbs: Hejazi ما اعرف /maː aʕrif/ ("I don't know"), as opposed to Egyptian معرفش /maʕrafʃ/ and Palestinian بعرفش /baʕrafiʃ/.

- The present indicative tense is not marked by any prefixes as in يِدْرُس /jidrus/ ("he studies"), as opposed to Egyptian بيدرس.

- The prohibitive mood of Classical Arabic is preserved in the imperative: لا تروح /laː tiruːħ/ ("don't go").

- The possessive suffixes are generally preserved in their Classical forms. For example, بيتكم /beːtakum/ "your (pl) house".

- The plural first person pronoun is نحنا / نِحْنَ /niħna/ or إحنا /iħna/, as opposed to the bedouin حنّا /ħənna/ or إنّا /ənna/.

- When indicating a location, the preposition في /fi/ (also written as a prefix فِـ) is preferred to بـ /b/. In bedouin dialects, the preference differs by region.

- The pronunciation of the ⟨ض⟩ is /dˤ/ as in Modern Standard Arabic.

- The hamzated verbs like أخذ /axad/ and أكل /akal/ keep their classical form as opposed to خذا /xaða/ and كلى /kala/.

- The glottal stop can be added to final syllables ending in a vowel as a way of emphasising.

- the definite article الـ is pronounced /al/ as opposed to Egyptian or Kuwaiti /il/.

- Compared to neighboring dialects, urban Hejazi retains most of the short vowels of Classical Arabic with no vowel reduction, for example:

- سمكة /samaka/ ("fish"), as opposed to bedouin [sməka].

- نُطْق /nutˤg/ ("pronunciation"), as opposed to bedouin [nətˤg].

- ضربَته /dˤarabatu/ ("she hit him"), as opposed to bedouin [ðˤrabətah].

- وَلَدُه /waladu/ ("his son"), as opposed to bedouin [wlədah].

- عندَكُم /ʕindakum/ ("in your possession" pl.), as opposed to bedouin [ʕəndəkum], Egyptian /ʕanduku/, and Levantine /ʕandkon/.

- عَلَيَّ /ʕalajːa/ ("on me"), as opposed to /ʕalaj/.

History

The Arabic of today is derived principally from the old dialects of Central and North Arabia which were divided by the classical Arab grammarians into three groups: Hejaz, Najd, and the language of the tribes in adjoining areas. Though the modern Hejazi dialects has developed markedly since the development of Classical Arabic, and Modern Standard Arabic is quite distinct from the modern dialect of Hejaz. Standard Arabic now differs considerably from modern Hejazi Arabic in terms of its phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexicon,[6] such diglossia in Arabic began to emerge at the latest in the sixth century CE when oral poets recited their poetry in a proto-Classical Arabic based on archaic dialects which differed greatly from their own.[7]

Historically, it is not well known in which stage of Arabic the shift from the Proto-Semitic pair /kʼ/ qāf and /g/ gīm came to be Hejazi /g, d͡ʒ/ ⟨ج, ق⟩ gāf and jīm, although it has been attested as early as the eighth century CE, and it can be explained by a chain shift /kʼ/* → /g/ → /d͡ʒ/[8] that occurred in one of two ways:

- Drag Chain: Proto-Semitic gīm /g/ palatalized to Hejazi /d͡ʒ/ jīm first, opening up a space at the position of [g], which qāf /kʼ/* then moved to fill the empty space resulting in Hejazi /g/ gāf, restoring structural symmetrical relationships present in the pre-Arabic system.[9][10]

- Push Chain: Proto-Semitic qāf /kʼ/* changed to Hejazi /g/ gāf first, which resulted in pushing the original gīm /g/ forward in articulation to become Hejazi /d͡ʒ/ jīm, but since most modern qāf dialects as well as standard Arabic also have jīm, hence the push-chain of qāf to gāf first can be discredited,[11] although there are good grounds for believing that old Arabic qāf had both voiced [g] and voiceless [q] allophones; and after that gīm /g/ was fronted to /d͡ʒ/ jīm, possibly as a result of pressure from the allophones.[12]

* The original value of Proto-Semitic qāf was probably an emphatic [kʼ] not [q].

Phonology

In general, Hejazi native phonemic inventory consists of 26 (with no interdental /θ, ð/) to 28 consonant phonemes depending on the speaker's background and formality, in addition to the marginal phoneme /ɫ/ and two foreign phonemes /p/ ⟨پ⟩ and /v/ ⟨ڤ⟩ used by a number of speakers. Furthermore, it has an eight-vowel system, consisting of three short and five long vowels /a, u, i, aː, uː, oː, iː, eː/, in addition to two diphthongs /aw, aj/.[13][14] Consonant length and Vowel length are both distinctive in Hejazi.

The main conservative phonological feature that urban Hejazi holds in contrast to the neighboring urban and rural dialects of the Arabian peninsula, is the constant use of full vowels and the absence of vowel reduction, for example قلنا لهم 'we told them', is pronounced [gʊlnaːlahʊm] in Hejazi with full vowels but pronounced with the reduced vowel [ə] as [gəlnaːləhəm] in Najdi. In general it also retains the distinction between the letters ⟨ض⟩ and ⟨ظ⟩, but alternates between the pronunciations of the letters ⟨ث⟩ ,⟨ذ⟩, and ⟨ظ⟩ which is a divergent feature. (See Hejazi Arabic Phonology)

Another feature that differentiates Hejazi is the lack is the lack of palatalization for the letters ك /k/, ق /g/ and ج /d͡ʒ/, unlike in other peninsular dialects where they can be palatalized and merged with other phonemes in certain positions[15] e.g. Hejazi جديد 'new' [d͡ʒadiːd] vs Gulf Arabic [jɪdiːd], it is also worth mentioning that this trait of non-palatalization is becoming common across Saudi Arabia especially in urban centers, another feature is that the ل /l/ is only velarized /ɫ/ in the word الله /aɫːaːh/ 'god' (except when it follows an /i/: بسمِ الله /bismilːaːh/ or لله /lilːaːh/) and in words derived from it, unlike other peninsular dialects where it might be velarized allophonically, as in عقل pronounced [ʕaɡe̞l] in Hejazi but [ʕaɡəɫ] in other peninsular Arabic dialects.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Occlusive | voiceless | (p) | t | tˤ | k | ʔ | |||

| voiced | b | d | dˤ | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ* | s | sˤ | ʃ | x | ħ | h |

| voiced | (v) | ð* | z | zˤ | ɣ | ʕ | |||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | (ɫ) | j | w | |||||

Phonetic notes:

- due to the influence of Modern Standard Arabic in the 20th century, [q] has been introduced as an allophone of /ɡ/ ⟨ق⟩ in a number of words and phrases as in القاهرة ('Cairo') which is phonemically /alˈgaːhira/ but can be pronounced as [alˈqaːhɪra] or less likely [alˈgaːhɪra] depending on the speaker, although older speakers prefer [g] in all positions.

- the marginal phoneme /ɫ/ only occurs in the word الله /aɫːaːh/ ('god') and words derived from it, it contrasts with /l/ in والله /waɫːa/ ('i swear') vs. ولَّا /walːa/ ('or').

- the affricate /d͡ʒ/ ⟨ج⟩ and the trill /r/ ⟨ر⟩ are realised as a [ʒ] and a tap [ɾ] respectively by a number of speakers or in a number of words.

- the reintroduced phoneme /θ/ ⟨ث⟩ is partially used as an alternative phoneme, while most speakers merge it with /t/ or /s/ depending on the word.

- the reintroduced phoneme /ð/ ⟨ذ⟩ is partially used as an alternative phoneme, while most speakers merge it with /d/ or /z/ depending on the word.

- [ðˤ] is an optional allophone for ⟨ظ⟩. In general, urban Hejazi speakers merge it with /dˤ/ or pronounce it distinctly as /zˤ/ depending on the word.

- /p/ ⟨پ⟩ and /v/ ⟨ڤ⟩ which exist only in foreign words, are used by a number of speakers and can be substituted by /b/ ⟨ب⟩ and /f/ ⟨ف⟩ respectively depending on the speaker.

- [tʃ] occurs only in foreign words and it is not considered to be part of the phonemic inventory but as a sequence of /t/ ⟨ت⟩ and /ʃ/ ⟨ش⟩, as in تشيلي /ˈtʃiːli/ or /tʃiːleː/ ('Chile').

Vowels

| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | eː | oː | ||

| Open | a | aː | ||

Phonetic notes:

- /a/ and /aː/ are pronounced either as an open front vowel [a] or an open central vowel [ä] depending on the speaker, even when adjacent to emphatic consonants, except in some words such as ألمانيا [almɑːnja] ('Germany'), يابان [jaːbɑːn] ('Japan') and بابا [bɑːbɑ] ('dad') where they are pronounced with the back vowel [ɑ].

- /oː/ and /eː/ are pronounced as true mid vowels [o̞ː] and [e̞ː] respectively.

- short /u/ (also analyzed as /ʊ/) is pronounced allophonically as [ʊ] or [o̞] in word initial or medial syllables and strictly as [u] at the end of words or before [w] or when isolate.

- short /i/ (also analyzed as /ɪ/)i s pronounced allophonically as [ɪ] or [e̞] in word initial or medial syllables and strictly as [i] at the end of words or before [j] or when isolate.

- the close vowels can be distinguished by tenseness with /uː/ and /iː/ being more tense in articulation than their short counterparts [ʊ ~ o̞] and [ɪ ~ e̞], except at the end of words.

Monophthongization

Most of the occurrences of the two diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ in the Classical Arabic period underwent monophthongization in Hejazi, and are realized as the long vowels /eː/ and /oː/ respectively, but they are still preserved as diphthongs in a number of words which created a contrast with the long vowels /uː/, /oː/, /iː/ and /eː/.

| Example (without diacritics) | Meaning | Hejazi Arabic | Modern Standard Arabic |

|---|---|---|---|

| دوري | league | /dawri/ | /dawri/ |

| my turn | /doːri/ | ||

| turn around! | /duːri/ | /duːri/ | |

| search! | /dawːiri/ | /dawːiri/ |

Not all instances of mid vowels are a result of monophthongization, some are from grammatical processes قالوا /gaːlu/ 'they said' → قالوا لها /gaːloːlaha/ 'they said to her' (opposed to Classical Arabic قالوا لها /qaːluː lahaː/), and some occur in modern Portmanteau words e.g. ليش /leːʃ/ 'why?' (from Classical Arabic لأي /liʔaj/ 'for what' and شيء /ʃajʔ/ 'thing').

Vocabulary

Hejazi vocabulary derives primarily from Arabic Semitic roots. The urban Hejazi vocabulary differs in some respect from that of other dialects in the Arabian Peninsula. For example, there are fewer specialized terms related to desert life, and more terms related to seafaring and fishing. Loanwords are uncommon but they are mainly of Persian, Turkish, Latin (French and Italian) and English origins, and due to the diverse origins of the inhabitants of Hejazi cities, some loanwords are only used by some families. some old loanwords are fading or became obsolete due to the influence of Modern Standard Arabic and their association with lower social class and education, e.g. كنديشن /kunˈdeːʃan/ "air conditioner" (from English Condition) was replaced by Standard Arabic مكيّف /mukajːif/. Most of the loanwords are nouns, with a change of meaning sometimes as in: كُبري /kubri/ "overpass" from كوپرى /køpri/ originally meaning "bridge" and وَايْت /waːjt/ "water tanker truck" from English white /waɪt/ and جزمة /d͡ʒazma/ "shoe" from Ottoman Turkish چزمه /t͡ʃizme/ originally meaning "boot".

Some general Hejazi expressions include بالتوفيق /bitːawfiːg/ "good luck", إيوه /ʔiːwa/ "yes", لأ /laʔ/ "no", لسة /lisːa/ "not yet, still", قد /ɡid/ or قيد /ɡiːd/ "already",[16] دحين /daħiːn/ or /daħeːn/ "now", أبغى /ʔabɣa/ "I want", لو سمحت /law samaħt/ "please/excuse me" to a male and لو سمحتي /law samaħti/ "please/excuse me" to a female.

Portmanteau

A common feature in Hejazi vocabulary is portmanteau words (also called a blend in linguistics); in which parts of multiple words or their phones (sounds) are combined into a new word, it is especially innovative in making Interrogative words, examples include:

- إيوه (/ʔiːwa/, "yes") : from إي (/ʔiː/, "yes") and و (/wa/, "and") and الله (/aɫːaːh/, "god").

- معليش (/maʕleːʃ/, is it ok?/sorry) : from ما (/maː/, nothing) and عليه (/ʕalajh/, on him) and شيء (/ʃajʔ/, thing).

- إيش (/ʔeːʃ/, "what?") : from أي (/aj/, "which") and شيء (/ʃajʔ/, "thing").

- ليش (/leːʃ/, "why?") : from لأي (/liʔaj/, for what) and شيء (/ʃajʔ/, "thing").

- فين (/feːn/, where?) : from في (/fiː/, in) and أين (/ʔajn/, where).

- إلين (/ʔileːn/, "until") : from إلى (/ʔilaː/, "to") and أن (/an/, "that").

- دحين (/daħiːn/ or /daħeːn/, "now") or ذحين (/ðaħiːn/ or /ðaħeːn/, "now") : from ذا (/ðaː/, "this") and الحين (/alħiːn/, part of time).

- بعدين (/baʕdeːn/, later) : from بعد (baʕd, after) and أَيْن (ʔayn, part of time).

- علشان or عشان (/ʕalaʃaːn/ or /ʕaʃaːn/, "in order to") : from على (/ʕalaː/, "on") and شأن (/ʃaʔn/, "matter").

- كمان (/kamaːn/, "also") : from كما (/kamaː/, "like") and أن (/ʔan/, "that").

- يلّا (/jaɫːa/, come on) : from يا (/jaː/, "o!") and الله (/aɫːaːh/, "god").

- لسة (/lisːa/, not yet, still) : from للساعة (/lisːaːʕa/, "to the hour") also used as in لِسّاعه صغير /lisːaːʕu sˤaɣiːr/ ("he is still young")

Numerals

The Cardinal number system in Hejazi is much more simplified than the Classical Arabic[17]

| numbers 1-10 | IPA | 11-20 | IPA | 10s | IPA | 100s | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 واحد | /waːħid/ | 11 احدعش | /iħdaʕaʃ/ | 10 عشرة | /ʕaʃara/ | 100 مية | /mijːa/ |

| 2 اثنين | /itneːn/ or /iθneːn/ | 12 اثنعش | /itˤnaʕaʃ/ or /iθnaʕaʃ/ | 20 عشرين | /ʕiʃriːn/ | 200 ميتين | /mijteːn/ or /mijːateːn/ |

| 3 ثلاثة | /talaːta/ or /θalaːθa/ | 13 ثلثطعش | /talat.tˤaʕaʃ/ or /θalaθ.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 30 ثلاثين | /talaːtiːn/ or /θalaːθiːn/ | 300 ثلثميَّة | /tultumijːa/ or /θulθumijːa/ |

| 4 أربعة | /arbaʕa/ | 14 أربعطعش | /arbaʕ.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 40 أربعين | /arbiʕiːn/ | 400 أربعميَّة | /urbuʕmijːa/ |

| 5 خمسة | /xamsa/ | 15 خمسطعش | /xamis.tˤaʕaʃ/ or /xamas.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 50 خمسين | /xamsiːn/ | 500 خمسميَّة | /xumsumijːa/ |

| 6 ستة | /sitːa/ | 16 ستطعش | /sit.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 60 ستين | /sitːiːn/ | 600 ستميَّة | /sutːumijːa/ |

| 7 سبعة | /sabʕa/ | 17 سبعطعش | /sabaʕ.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 70 سبعين | /sabʕiːn/ | 700 سبعميَّة | /subʕumijːa/ |

| 8 ثمنية | /tamanja/ or /θamanja/ | 18 ثمنطعش | /taman.tˤaʕaʃ/ or /θaman.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 80 ثمانين | /tamaːniːn/ or /θamaːniːn/ | 800 ثمنميَّة | /tumnumijːa/ or /θumnumijːa/ |

| 9 تسعة | /tisʕa/ | 19 تسعطعش | /tisaʕ.tˤaʕaʃ/ | 90 تسعين | /tisʕiːn/ | 900 تسعميَّة | /tusʕumijːa/ |

| 10 عشرة | /ʕaʃara/ | 20 عشرين | /ʕiʃriːn/ | 100 ميَّة | /mijːa/ | 1000 ألف | /alf/ |

A system similar to the German numbers system is used for other numbers between 20 and above : 21 is واحد و عشرين /waːħid u ʕiʃriːn/ which literally mean ('one and twenty') and 485 is أربعمية و خمسة و ثمانين /urbuʕmijːa u xamsa u tamaːniːn/ which literally mean ('four hundred and five and eighty').

Unlike Classical Arabic, the only number that is gender specific in Hejazi is "one" which has two forms واحد m. and وحدة f. as in كتاب واحد /kitaːb waːħid/ ('one book') or سيارة وحدة /sajːaːra waħda/ ('one car'), with كتاب being a masculine noun and سيّارة a feminine noun.

- for 2 as in 'two cars' 'two years' 'two houses' etc. the dual form is used instead of the number with the suffix ēn /eːn/ or tēn /teːn/ (if the noun ends with a feminine /a/) as in كتابين /kitaːbeːn/ ('two books') or سيّارتين /sajːarateːn/ ('two cars'), for emphasis they can be said as كتابين اثنين or سيّارتين اثنين.

- for numbers 3 to 10 the noun following the number is in plural form as in اربعة كتب /arbaʕa kutub/ ('4 books') or عشرة سيّارات /ʕaʃara sajːaːraːt/ ('10 cars').

- for numbers 11 and above the noun following the number is in singular form as in :-

- from 11 to 19 an ـر [ar] is added to the end of the numbers as in اربعطعشر كتاب /arbaʕtˤaʕʃar kitaːb/ ('14 books') or احدعشر سيّارة /iħdaʕʃar sajːaːra/ ('11 cars').

- for 100s a [t] is added to the end of the numbers before the counted nouns as in ثلثميّة سيّارة /tultumijːat sajːaːra/ ('300 cars').

- other numbers are simply added to the singular form of the noun واحد و عشرين كتاب /waːħid u ʕiʃriːn kitaːb/ ('21 books').

Grammar

Subject pronouns

In Hejazi Arabic, personal pronouns have eight forms. In singular, the 2nd and 3rd persons differentiate gender, while the 1st person and plural do not. The negative articles include لا /laː/ as in لا تكتب /laː tiktub/ ('do not write!'), ما /maː/ as in ما بيتكلم /maː bijitkalːam/ ('he is not talking') and مو /muː/ as in مو كذا /muː kida/ ('not like this')

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Verbs

Hejazi Arabic verbs, as with the verbs in other Semitic languages, and the entire vocabulary in those languages, are based on a set of three, four, or even five consonants (but mainly three consonants) called a root (triliteral or quadriliteral according to the number of consonants). The root communicates the basic meaning of the verb, e.g. k-t-b 'to write', ʼ-k-l 'to eat'. Changes to the vowels in between the consonants, along with prefixes or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as :

- Two tenses (past, present; present progressive is indicated by the prefix (bi-), future is indicated by the prefix (ħa-))

- Two voices (active, passive)

- Two genders (masculine, feminine)

- Three persons (first, second, third)

- Two numbers (singular, plural)

Hejazi has two grammatical number in verbs (Singular and Plural) instead of the Classical (Singular, Dual and Plural), in addition to a present progressive tense which was not part of the Classical Arabic grammar. In contrast to other urban dialects the prefix (bi-) is only used for present continuous as in بِيِكْتُب /bijiktub/ "he is writing" while the habitual tense is without a prefix as in أَحُبِّك /aħubbik/ "I love you" f. unlike بحبِّك in Egyptian and Levantine dialects and the future tense is indicated by the prefix (ħa-) as in حَنِجْري /ħanid͡ʒri/ "we will run".

Regular verbs

The most common verbs in Hejazi have a given vowel pattern for past (a and i) to present (a or u or i). Combinations of each exist[18]:

| Vowel patterns | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Past | Present | |

| a | a | raħam رحم he forgave – yirħam يرحم he forgives |

| a | u | ḍarab ضرب he hit – yiḍrub يضرب he hits |

| a | i | ġasal غسل he washed – yiġsil يغسل he washes |

| i | a | fihim فهم he understood – yifham يفهم he understands |

| i | i | ʕirif عرف he knew – yiʕrif يعرف he knows |

According to Arab grammarians, verbs are divided into three categories; Past ماضي, Present مضارع and Imperative أمر. An example from the root k-t-b the verb katabt/ʼaktub 'i wrote/i write' (which is a regular sound verb):

| Tense/Mood | Past "wrote" | Present (Indicative) "write" | Imperative "write!" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | كتبت (katab)-t | كتبنا (katab)-na | أكتب ʼa-(ktub) | نكتب ni-(ktub) | |||

| 2nd | masculine | كتبت (katab)-t | كتبتوا (katab)-tu | تكتب ti-(ktub) | تكتبوا ti-(ktub)-u | أكتب [a]-(ktub) | أكتبوا [a]-(ktub)-u |

| feminine | كتبتي (katab)-ti | تكتبي ti-(ktub)-i | أكتبي [a]-(ktub)-i | ||||

| 3rd | masculine | كتب (katab) | كتبوا (katab)-u | يكتب yi-(ktub) | يكتبوا yi-(ktub)-u | ||

| feminine | كتبت (katab)-at | تكتب ti-(ktub) | |||||

While present progressive and future are indicated by adding the prefix (bi-) and (ħa-) respectively to the present (indicative) :

| Tense/Mood | Present Progressive "writing" | Future "will write" | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | بكتب or بأكتب ba-a-(ktub) | بنكتب bi-ni-(ktub) | حكتب or حأكتب ħa-a-(ktub) | حنكتب ħa-ni-(ktub) | |

| 2nd | masculine | بتكتب bi-ti-(ktub) | بتكتبوا bi-ti-(ktub)-u | حتكتب ħa-ti-(ktub) | حتكتبوا ħa-ti-(ktub)-u |

| feminine | بتكتبي bi-ti-(ktub)-i | حتكتبي ħa-ti-(ktub)-i | |||

| 3rd | masculine | بيكتب bi-yi-(ktub) | بيكتبوا bi-yi-(ktub)-u | حيكتب ħa-yi-(ktub) | حيكتبوا ħa-yi-(ktub)-u |

| feminine | بتكتب bi-ti-(ktub) | حتكتب ħa-ti-(ktub) | |||

- additional final ا to ـوا /-u/ in all plural verbs is silent.

- The Active Participles قاعد /gaːʕid/, قاعدة /gaːʕda/ and قاعدين /gaːʕdiːn/ can be used instead of the prefix بـ [b-] as in قاعد اكتب /gaːʕid aktub/ ('i'm writing') instead of بأكتب/ بكتب /baktub/ / /baʔaktub/ ('i'm writing') without any change in the meaning.

- the 3rd person past plural suffix -/u/ turns into -/oː/ (long o) instead of -/uː/ before pronouns, as in راحوا /raːħu/ ('they went') → راحوا له /raːħoːlu/ ('they went to him'), or it can be originally an -/oː/ as in جوا /d͡ʒoː/ ('they came') and in its homophone جوه /d͡ʒoː/ ('they came to him') since the word-final 3rd person masculine singular pronoun ـه is silent.

- the verbs highlighted in silver sometimes come in irregular forms e.g. حبيت (ħabbē)-t "i loved", حبينا (ħabbē)-na "we loved" but ّحب (ħabb) "he loved" and حبُّوا (ħabb)-u "they loved".

- word-final hollow verbs have a unique conjugation of either /iːt/ or /eːt/, if a verb ends in ـي /i/ in its past simple form as in نسي nisi 'he forgot' (present ينسى yinsa 'he forgets') it becomes نسيت nisīt 'I forgot' and نسيت nisyat 'she forgot' this rule is used in verbs رضي riḍi, صِحِي ṣiḥi, لقي ligi. While if the verb ends in ـى /a/ in its past simple form as in شوى šawa 'he grilled' (present يشوي yišwi 'he grills') it becomes شَويت šawēt 'I grilled' and شَوَت šawat 'she grilled. Most of these verbs correspond to their Classical Arabic forms, but some exceptions include بكي biki 'he cried', جري jiri 'he ran', مشي miši 'he walked' and دري diri 'he knew' as opposed to the Classical بكى baka, جرى jara, مشى maša, درى dara.

Example: katabt/aktub "write": non-finite forms

| Number/Gender | اسم الفاعل Active Participle | اسم المفعول Passive Participle | مصدر Verbal Noun |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masc. Sg. | kātib كاتب | maktūb مكتوب | kitāba كتابة |

| Fem. Sg. | kātb-a كاتبة | maktūb-a مكتوبة | |

| Pl. | kātb-īn كاتبين | maktūb-īn مكتوبين |

Active participles act as adjectives, and so they must agree with their subject. An active participle can be used in several ways:

- to describe a state of being (understanding; knowing).

- to describe what someone is doing right now (going, leaving) as in some verbs like رحت ("i went") the active participle رايح ("i'm going") is used instead of present continuous form to give the same meaning of an ongoing action.

- to indicate that someone/something is in a state of having done something (having put something somewhere, having lived somewhere for a period of time).

Passive Voice

The passive voice is expressed through two patterns; (أَنْفَعَل /anfaʕal/, يِنْفَعِل /jinfaʕil/) or (أتْفَعَل /atfaʕal/, يِتْفَعِل /jitfaʕil/), while most verbs can take either pattern as in أتكتب /atkatab/ or أنكتب /ankatab/ "it was written" and يتكتب /jitkatib/ or ينكتب /jinkatib/ "it is being written", other verbs can only have one of the two patterns as in أتوقف /atwagːaf/ "he was stopped" and يتوقف /jitwagːaf/ "he is being stopped".

Pronouns

Enclitic pronouns

Enclitic forms of personal pronouns are suffixes that are affixed to various parts of speech, with varying meanings:

- To the construct state of nouns, where they have the meaning of possessive demonstratives, e.g. "my, your, his".

- To verbs, where they have the meaning of direct object pronouns, e.g. "me, you, him".

- To verbs, where they have the meaning of indirect object pronouns, e.g. "(to/for) me,(to/for) you, (to/for) him".

- To prepositions.

Unlike Egyptian Arabic, in Hejazi no more than one pronoun can be suffixed to a word.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ^1 if a noun ends with a vowel (other than the /-a/ of the feminine nouns) that is /u/ or /a/ then the suffix (-ya) is used as in أبو /abu/ ('father') becomes َابوي /abuːja/ ('my father') but if it ends with an /i/ then the suffix (-yya) is added as in َّكرسي /kursijːa/ ('my chair').

- ^2 the colon between the parentheses -[ː] indicates that the final vowel of a word is lengthened as in كرسي /kursi/ ('chair') → كرسيه /kursiː/ ('his chair'), since the word-final ـه [h] is silent in this position. although in general it is uncommon for Hejazi nouns to end in a vowel other than the /-a/ of the feminine nouns.

- The indirect object pronouns are written separately from the verbs as per Classical Arabic convention, but they are pronounced as if they are fused with the verbs. They are still written intact by many writers as in كتبت له /katabtalːu/ ('i wrote to him') which is written كتبتله since Hejazi does not have a written standard.

General Modifications:-

- When a noun ends in a feminine /a/ vowel as in مدرسة /madrasa/ ('school') : a /t/ is added before the suffixes as in → مدرستي /madrasati/ ('my school'), مدرسته /madrasatu/ ('his school'), مدرستها /madrasatha/ ('her school') and so on.

- After a word ends in a vowel (other than the /-a/ of the feminine nouns), the vowel is lengthened, and the pronouns in (vowel+) are used instead of their original counterparts :-

- the possessive pronouns as in كرسي /kursi/ ('chair') → كرسيه /kursiː/ ('his chair'), كرسينا /kursiːna/ ('our chair'), كرسيكي /kursiːki/ ('your chair' f.)

- the direct object pronouns لاحقنا /laːħagna/ ('we followed') → لاحقناه /laːħagnaː/ ('we followed him'), لاحقناكي /laːħagnaːki/ ('we followed you' feminine).

- After a word that ends in two consonants, or which has a long vowel in the last syllable, /-a-/ is inserted before the 5 suffixes which begin with a consonant /-ni/, /-na/, /-ha/, /-hom/, /-kom/.

- the possessive pronouns كتاب /kitaːb/ ('book') → كتابها /kitaːbaha/ ('her book'), كتابهم /kitaːbahum/ ('their book'), كتابكم /kitaːbakum/ ('your book' plural), كتابنا /kitaːbana/ ('our book').

- the direct object pronouns عرفت /ʕirift/ ('you knew') → عرفتني /ʕiriftani/ ('you knew me'), عرفتنا /ʕiriftana/ ('you knew us'), عرفتها /ʕiriftaha/ ('you knew her'), عرفتهم /ʕiriftahum/ ('you knew them').

- the indirect object pronouns رحنا /ruħna/ ('we went') → رحنا له /ruħnaːlu/ ('we went to him').

- the 3rd person past plural suffix -/u/ turns into -/oː/ (long o) before pronouns, as in عرفوا /ʕirfu/ ('they knew') → عرفوني /ʕirfoːni/ ('they knew me'), راحوا /raːħu/ ('they went') → راحوا له /raːħoːlu/ ('they went to him') or كتبوا /katabu/ ('they wrote') → كتبوا لي /kataboːli/ ('they wrote to me')

- When a verb ends in two consonants as in رحت /ruħt/ ('i went' or 'you went') : an /-al-/ is added before the Indirect object pronoun suffixes → رحت له /ruħtalːu/ ('i went to him') or in كتبت /katabt/ ('I wrote' or 'you wrote') becomes كتبت له /katabtalːu/ ('i wrote to him'), كتبت لهم /katabtalːahum/ ('i wrote to them').

Modifications to Hollow Verbs (verbs with medial vowels و ū, ي ī or ا ā) when added to Indirect object pronouns (vowel shortening)[20]:

| Tense/Mood | Past "went" (ruḥ) | Present (Indicative) "goes" (rūḥ) | Imperative "go!" (rūḥ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | رحت ruḥt | رحنا ruḥna | أروح ʼarūḥ | نروح nirūḥ | |||

| 2nd | masculine | رحت ruḥt | رحتوا ruḥtu | تروح tirūḥ | تروحوا tirūḥu | روح rūḥ | روحوا rūḥu |

| feminine | رحتي ruḥti | تروحي tirūḥi | روحي rūḥi | ||||

| 3rd | masculine | راح rāḥ | راحوا rāḥu | يروح yirūḥ | يروحوا yirūḥu | ||

| feminine | راحت rāḥat | تروح tirūḥ | |||||

- when a verb has a long vowel in the last syllable (shown in silver in the main example) as in أروح /aruːħ/ ('I go'), يروح /jiruːħ/ (he goes) or نروح /niruːħ/ (''we go'); the vowel is shortened before the suffixes as in أرُح له /aruħlu/ (I go to him), يرح له /jiruħlu/ (he goes to him) and نرُح له /niruħlu/ (we go to him) with the verbs resembling the Jussive (مجزوم majzūm) mood conjugation in Classical Arabic (shown in gold in the example), original forms as in أرُوح له or يروح له can be used depending on the writer but the vowels are still shortened in pronunciation.

- This does effect past verbs as well but the form of the word does not change, as in راح /raːħ/ rāḥ ('he went') which is pronounced راح له /raħlu/ ('he went to him!') after adding a pronoun.

- Other hollow verbs include أعيد /ʔaʕiːd/ ('I repeat') or قول /guːl/ ('say!') which become أعِيد لك / أعِد لك /ʔaʕidlak/ ('I repeat for you') and قُول لها / قُل لها /gulːaha/ ('tell her!')

| Tense/Mood | Past "went" | Present (Indicative) "write" | Imperative "write!" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | رحت له ruḥt-allu | رحنا له ruḥnā-lu | أرح له or أروح له ʼaruḥ-lu | نرح له or نروح له niruḥ-lu | |||

| 2nd | masculine | رحت له ruḥt-allu | رحتوا له ruḥtū-lu | ترح له or تروح له tiruḥ-lu | تروحوا له tirūḥū-lu | رح له or روح له ruḥ-lu | روحوا له rūḥū-lu |

| feminine | رحتي له ruḥtī-lu | تروحي له tirūḥī-lu | روحي له rūḥī-lu | ||||

| 3rd | masculine | راح له raḥ-lu | راحوا له rāḥō-lu | يرح له or يروح له yiruḥ-lu | يروحوا له yirūḥū-lu | ||

| feminine | راحت له rāḥat-lu | ترح له or تروح له tiruḥ-lu | |||||

The phrase "for me" is لِيّ /lijːa/ while other phrases "for her" can be لِيها /liːha/ or لَهَا /laha/, "for him" لِيه /liː/ or لُه /lu(h)/ and so on.

Writing system

Hejazi is written using the Arabic alphabet; like other varieties of Arabic, Hejazi does not have a standard form of writing and mostly follows Classical Arabic rules of writing.[21] In general people alternate between writing the words according to their etymology or the phoneme used while pronouncing them, which mainly has an effect on the three letters ⟨ث⟩ ⟨ذ⟩ and ⟨ظ⟩, for example writing تخين instead of ثخين or ديل instead of ذيل although this alternation in writing is not considered acceptable by all Hejazi speakers.

Another alternation which is more likely to appear happens when writing words that end in a short vowel /a, u, i/, the writer would choose whether to add a vowel letter ⟨و⟩ ⟨ا⟩ or ⟨ي⟩ at the end of the word as in انتي /inti/ ('you' singular feminine) to differentiate it from انت /inta/ ('you' singular masculine), or use the Classical form انت which can be pronounced /inta/ or /inti/, this happens since most word-final short vowels from the Classical Arabic period have been omitted and most word-final unstressed long vowel letters have been shortened in Hejazi. In Arabic handwriting of everyday use, in general publications, and on street signs, short vowels are typically not written, and when needed to be written they are written in a form of diacritics; ـَ above the letter for /a/, ـُ above the letter for /u/, ـِ under the letter for /i/.

The table below shows the Arabic alphabet letters and their corresponding phonemes in Hejazi:

| Letter | Phonemes / Allophones (IPA) | Example | Pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ا | /ʔ/ (see ⟨ء⟩ Hamza). | سَأَل "he asked" | /saʔal/ | |

| /aː/ | باب "door" | /baːb/ | ||

| /a/ | when word-final and unstressed (when word-final and stressed it's /aː/) | شُفْنا "we saw", (ذا m. "this") | /ˈʃufna/, (/ˈdaː/ or /ˈðaː/) | |

| in 3rd person masculine past verbs before indirect object pronouns e.g. لي ,له ,لها and some words | قال لي "he told me", راح لَها "he went to her" | /galːi/, /raħlaha/ | ||

| additional ∅ silent word-final only in plural verbs and after nunation | دِرْيُوا "they knew", شُكْرًا "thanks" | /dirju/, /ʃukran/ | ||

| ب | /b/ | بِسَّة "cat" | /bisːa/ | |

| ت | /t/ | توت "berry" | /tuːt/ | |

| ث | ||||

| either /t/ | or always/in some words as /θ/ | ثَلْج "snow" | /tald͡ʒ/ or /θald͡ʒ/ | |

| or /s/ | ثابِت "stable" | /saːbit/ or /θaːbit/ | ||

| ج | /d͡ʒ/ | جَوَّال "mobile phone" | /d͡ʒawːaːl/ | |

| ح | /ħ/ | حوش "courtyard" | /ħoːʃ/ | |

| خ | /x/ | خِرْقة "rag" | /xirga/ | |

| د | /d/ | دولاب "closet" | /doːˈlaːb/ | |

| ذ | ||||

| either /d/ | or always/in some words as /ð/ | ذيل "tail" | /deːl/ or /ðeːl/ | |

| or /z/ | ذوق "taste" | /zoːg/ or /ðoːg/ | ||

| ر | /r/ | رَمِل "sand" | /ramil/ | |

| ز | /z/ | زُحْليقة "slide" | /zuħleːga/ | |

| س | /s/ | سَقْف "roof" | /sagf/ | |

| ش | /ʃ/ | شيوَل "loader" | /ʃeːwal/ | |

| ص | /sˤ/ | صُفِّيرة "whistle" | /sˤuˈfːeːra/ | |

| ض | /dˤ/ | ضِرْس "molar" | /dˤirs/ | |

| ط | /tˤ/ | طُرْقة "corridor" | /tˤurga/ | |

| ظ | ||||

| either /dˤ/ | or always/in some words as [ðˤ] (allophone) | ظِل "shade" | /dˤilː/ or [ðˤɪlː] | |

| or /zˤ/ | ظَرْف "envelope, case" | /zˤarf/ or [ðˤarf] | ||

| ع | /ʕ/ | عين "eye" | /ʕeːn/ | |

| غ | /ɣ/ | غُراب "crow" | /ɣuraːb/ | |

| ف | /f/ | فَم "mouth" | /famː/ | |

| ق | /g/ (pronounced [q] (allophone) in a number of words) | قَلْب "heart" (قِمَّة "peak") | /galb/ (/gimːa/ or [qɪmːa]) | |

| ك | /k/ | كَلْب "dog" | /kalb/ | |

| ل | /l/ (marginal phoneme /ɫ/ only in the word الله and words derived from it) | ليش؟ "why?", (الله "god") | /leːʃ/, (/aɫːaːh/) | |

| م | /m/ | مويَة "water" | /moːja/ | |

| ن | /n/ | نَجَفة "chandelier" | /nad͡ʒafa/ | |

| هـ | /h/ (silent when word-final in 3rd person masculine singular pronouns and some words) | هَوا "air", (كِتابُه "his book", شافوه "they saw him") | /hawa/, (/kitaːbu/, /ʃaːˈfoː/) | |

| و | /w/ | وَرْدة "rose" | /warda/ | |

| /uː/ | فوق "wake up!" | /fuːg/ | ||

| /oː/ | فوق "above, up" | /foːg/ | ||

| /u/ only when word-final and unstressed (when word-final and stressed it's either /uː/ or /oː/) | رَبو "asthma", (مو "is not", جوا "they came") | /ˈrabu/, (/ˈmuː/, /ˈd͡ʒoː/) | ||

| ي | /j/ | يَد "hand" | /jadː/ | |

| /iː/ | بيض "whites pl." | /biːdˤ/ | ||

| /eː/ | بيض "eggs" | /beːdˤ/ | ||

| /i/ only when word-final and unstressed (when word-final and stressed it's either /iː/ or /eː/) | سُعُودي "saudi", (ذي f. "this", عليه "on him") | /suˈʕuːdi/, (/ˈdiː/, /ʕaˈleː/) | ||

| Additional non-native letters | ||||

| پ | /p/ (can be written and/or pronounced as ⟨ب⟩ /b/ depending on the speaker) | پيتزا or بيتزا "pizza" | /piːtza/ or /biːtza/ | |

| ڤ | /v/ (can be written and/or pronounced as ⟨ف⟩ /f/ depending on the speaker) | ڤَيْروس or فَيْروس "virus" | /vajruːs/ or /fajruːs/ | |

Notes:

- Medial ⟨ا⟩ is short only in 3rd person masculine past verbs before indirect object pronouns e.g. لي ,له ,لها as in عاد /ʕaːd/ "he repeated" becomes عاد لهم /ʕadlahum/ "he repeated to them" and in few words as in جاي "I'm coming" pronounced /d͡ʒaj/ or /d͡ʒaːj/, the same "indirect object pronoun" vowel-shortening effect takes place with medial ⟨ي⟩ and ⟨و⟩ for example رايحين له "going to him" is mostly pronounced /raːjħinlu/ with a shortened /i/ and rarely /raːjħiːnlu/.

- ⟨ة⟩ is only used at the end of words and mainly to mark feminine gender for nouns and adjectives with few exceptions (e.g. أسامة; a male noun). phonemically it is silent indicating final /-a/, except when in construct state it is a /t/, which leads to the word-final /-at/. e.g. رسالة /risaːla/ 'message' → رسالة أحمد /risaːlat ʔaħmad/ 'Ahmad's message'.

- ⟨هـ⟩ /h/ is silent only word-final in some words and in 3rd person masculine singular pronoun, as in شفناه /ʃufˈnaː/ "we saw him" or the heteronym ليه pronounced /leː/ 'why?' or /liː/ 'for him', but the /h/ can be added for emphasis if needed. The silent ⟨هـ⟩ also helps in distinguishing minimal pairs with word-final vowel length contrast تبغي /tibɣi/ 'you want f.' vs. تبغيه /tibɣiː/ 'you want him f.'. but it is still maintained word-final in most other nouns as in فَواكِه /fawaːkih/ "fruits", كُرْه /kurh/ "hate" and أَبْلَه /ʔablah/ "idiot" where it is differentiated from أبلة /ʔabla/ "f. teacher".

- ⟨غ⟩ /ɣ/ and ⟨ج⟩ /d͡ʒ/ are sometimes used to transcribe /g/ in foreign words. ⟨غ⟩ is especially used in city/state names as in بلغراد "Belgrade" pronounced /bilgraːd/ or /bilɣraːd/, this ambiguity arised due to Standard Arabic not having a letter that transcribes /g/ distinctively, which created doublets like كتلوق /kataˈloːg/ vs. كتلوج /kataˈloːd͡ʒ/ "catalog" and قالون /gaːˈloːn/ vs. جالون /d͡ʒaːˈloːn/ "gallon". newer terms are more likely to be transcribed using the native ⟨ق⟩ as in إنستقرام /instagraːm/ "Instagram" and قروب /g(u)ruːb, -uːp/ "WhatsApp group".

- ⟨ض⟩ /dˤ/ is pronounced /zˤ/ only in few words from the two trilateral roots ⟨ض ب ط⟩ and ⟨ض ر ط⟩, as in ضبط ("it worked") pronounced /zˤabatˤ/ and not /dˤabatˤ/.

- The interdental consonants:

- ⟨ث⟩ represents /t/ as in ثوب /toːb/ & ثواب /tawaːb/ or /s/ as in ثابت /saːbit/, but the classical phoneme /θ/ is still used as well depending on the speaker especially in words of English origin.

- ⟨ذ⟩ represents /d/ as in ذيل /deːl/ & ذكر /dakar/ or /z/ as in ذكي /zaki/, but the classical phoneme /ð/ is still used as well depending on the speaker especially in words of English origin.

- ⟨ظ⟩ represents /dˤ/ as in ظفر /dˤifir/ & ظل /dˤilː/ or /zˤ/ as in ظرف /zˤarf/, but the classical [ðˤ] is still used as an allophone depending on the speaker.

Rural dialects

The varieties of Arabic spoken in the smaller towns and by the bedouin tribes in the Hejaz region are relatively under-studied. However, the speech of some tribes shows much closer affinity to other bedouin dialects, particularly those of neighboring Najd, than to those of the urban Hejazi cities. The dialects of northern Hejazi tribes merge into those of Jordan and Sinai, while the dialects in the south merge with those of 'Asir and Najd. Also, not all speakers of these bedouin dialects are figuratively nomadic bedouins; some are simply sedentary sections that live in rural areas, and thus speak dialects similar to those of their bedouin neighbors.

Al-`Ula

The dialect of Al-`Ula governorate in the northern part of the Madinah region. Although understudied, it is considered to be unique among the Hejazi dialects, it is known for its pronunciation of Classical Arabic ⟨ك⟩ /k/ as a ⟨ش⟩ /ʃ/ (e.g. تكذب /takðib/ becomes تشذب /taʃðib/), the dialect also shows a tendency to pronounce long /aː/ as [eː] (e.g. Classical ماء /maːʔ/ becomes ميء [meːʔ]), in some instances the Classical /q/ becomes a /d͡ʒ/ as in قايلة /qaːjla/ becomes جايلة /d͡ʒaːjla/, also the second person singular feminine pronoun /ik/ tends to be pronounced as /iʃ/ (e.g. رجلك /rid͡ʒlik/ ('your foot') becomes رجلش /rid͡ʒliʃ/.[22]

Badr

The dialect of Badr governorate in the western part of the Madinah region is mainly noted for its lengthening of word-final syllables and its alternative pronunciation of some phonemes as in سؤال /suʔaːl/ which is pronounced as سعال /suʕaːl/, it also shares some features with the general urban dialect in which modern standard Arabic ثلاجة /θalːaːd͡ʒa/ is pronounced تلاجة /talːaːd͡ʒa/, another unique feature of the dialect is its similarity to the Arabic dialects of Bahrain.

See also

References

- "Arabic, Hijazi Spoken". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Hijazi Arabic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Alzaidi (2014:73) Information Structure and Intonation in Hijazi Arabic.

- Il-Hazmy (1975:234)

- Alqahtani, Fatimah; Sanderson, Mark (2015). "Generating a Lexion for the Hijazi dialect of Arabic". Generating a Lexion for the Hijazi dialect of Arabic: 9.

- Watson, Janet (2002). The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic. Oxford university press. pp. 8, 9.

- Lipinski (1997). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. p. 75.

- Cantineau, Jean (1960). Cours de phonétique arabe (in French). Paris, France: Libraire C. Klincksieck. p. 67.

- Freeman, Aaron (2015). "The Linguistic Geography of Dorsal Consonants in Syria" (PDF). The Linguistic Geography of Dorsal Consonants in Syria. University of Pennsylvania.

- Öhrnberg, Kaj (2013). "Travelling Through Time". Studia Orientalia 114: 524.

- Heinrichs, Wolfhart. "Ibn Khaldūn as a Historical Linguist with an Excursus on the Question of Ancient gāf". Harvard University.

- Blanc 1969: 11, Travelling Through Time, Essays in honour of Kaj Öhrnberg

- Abdoh (2010:84)

- Omar, Margaret k. (1975). Saudi Arabia, Urban Hijazi dialect. pp. x.

- Owens, Owens. The Oxford Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. p. 259.

- Eifan, Emtenan (2017). "Grammaticalization in Urban Hijazi Arabic" (PDF). Grammaticalization in Urban Hijazi Arabic: 39.

- Kheshaifaty (1997) "Numerals: a comparative study between classical and hijazi arabic"

- Ahyad, Honaida; Becker, Michael (2020). "Vowel unpredictability in Hijazi Arabic monosyllabic verbs". Vowel unpredictability in Hijazi Arabic monosyllabic verbs.

- Omar (1975)

- Al-Mohanna Abaalkhail, Faisal (1998). "Syllabification and metrification in Urban Hijazi Arabic: between rules and constraints" (PDF). Syllabification and metrification in Urban Hijazi Arabic: between rules and constraints. Chapter 3: 119.

- Holes, Clive (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, Washington D.C. pp. 92.

- Aljuhani, Sultan (2008). "Spoken Al-'Ula dialect between privacy and fears of extinction. (in Arabic)".

- Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language, NITLE Arab World Project, by the permission of Edinburgh University Press,

- Ingham, Bruce (1971). "Some Characteristics of Meccan Speech". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. School of Oriental and African Studies. 34 (2): 273–97. ISSN 1474-0699. JSTOR 612692 – via JSTOR.

Bibliography

- Abdoh, Eman Mohammed (2010). A Study of the Phonological Structure and Representation of First Words in Arabic (PDF) (Thesis).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alzaidi, Muhammad Swaileh A. (2014). Information Structure and Intonation in Hijazi Arabic (PDF) (Thesis).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Omar, Margaret k. (1975). "Saudi Arabic, Urban Hijazi Dialect" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kheshaifaty, Hamza M.J. (1997). "Numerals: a comparative study between classical and hijazi arabic" (PDF). Journal of King Saud University, Arts. 9 (1): 19–36.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watson, Janet C. E. (2002). The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Il-Hazmy, Alayan (1975). A critical and comparative study of the spoken dialect of the Harb tribe in Saudi Arabia (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Hejazi Arabic test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |