Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World is a 2003 American epic period war-drama film co-written, produced and directed by Peter Weir, set in the Napoleonic Wars. The film's plot and characters are adapted from three novels in author Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey–Maturin series, which includes 20 completed novels of Jack Aubrey's naval career. The film stars Russell Crowe as Jack Aubrey, captain in the Royal Navy, and Paul Bettany as Dr. Stephen Maturin, the ship's surgeon. The film, which cost $150 million to make, was a co-production of 20th Century Fox, Miramax Films, Universal Pictures, and Samuel Goldwyn Films, and released on November 14, 2003. The film grossed $212 million worldwide.

| Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World | |

|---|---|

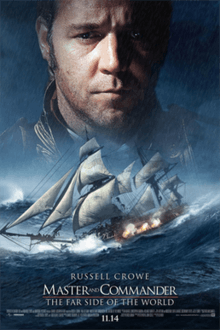

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Weir |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Master and Commander by Patrick O'Brian |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | Russell Boyd |

| Edited by | Lee Smith |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $150 million[3] |

| Box office | $212 million[3] |

The film was critically well received. At the 76th Academy Awards, the film was nominated for 10 Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. It won in two categories, Best Cinematography and Best Sound Editing and lost in all other categories to The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

Plot

During the Napoleonic Wars, Captain Jack Aubrey of HMS Surprise is ordered to fight the French privateer Acheron. Acheron ambushes Surprise, off the coast of Brazil causing heavy damage, while remaining undamaged by the British guns. The ship's boats tow Surprise into a fog bank to evade pursuit. Aubrey's officers tell him that Surprise is no match for Acheron, and that they should abandon the chase. Aubrey points out that Acheron must not be allowed to plunder the British whaling fleet. He orders Surprise refitted at sea, rather than returning to port for repairs. William Blakeney has his arm amputated due to injuries sustained in battle. Shortly afterwards, Acheron again ambushes Surprise, but Aubrey slips away in the night by using a decoy raft and ship's lamps.

Following the privateer south, Surprise rounds Cape Horn and heads to the Galapagos Islands, where Aubrey is convinced that Acheron will prey on Britain's whaling fleet. The ship's doctor, Maturin, is interested in the islands' unique flora and fauna, and Aubrey promises his friend several days' exploration time. When Surprise reaches the Galapagos, however, they recover the survivors of a whaling ship destroyed by Acheron. Aubrey hastily pursues the privateer, dashing Maturin's expectation of more time to explore.

Surprise is becalmed for several days. The crew becomes restless and disorderly. Midshipman Hollom, already unpopular with the crew, is named a "Jonah" by the sailors (someone who brings bad luck to a ship). As the tension rises, crew member Nagle refuses to salute Hollom on the deck, and is flogged for insubordination. That night, Hollom commits suicide by jumping overboard with a cannonball. The next morning, Aubrey holds a service for Hollom. The wind picks up again, and Surprise resumes the chase.

The next day, Royal Marine officer Captain Howard attempts to shoot an albatross but accidentally hits Maturin instead. The surgeon's mate informs Aubrey that the bullet and a piece of cloth it took with it must be removed soon, otherwise they will fester. He also recommends the delicate operation be performed on land. Despite closing on Acheron, Aubrey takes the doctor back to the Galapagos. Maturin performs surgery on himself using a mirror. Finally giving up the pursuit of the privateer, Aubrey grants Maturin the chance to explore the Galapagos islands and gather specimens before they head for home. While looking for a species of flightless cormorant, the doctor discovers Acheron on the other side of the island. Maturin abandons most of his specimens and hurries to warn Aubrey. Surprise readies for battle once more. Due to Acheron's stronger hull, Surprise must be at close quarters to damage her. After observing the camouflage ability of one of Maturin's specimens, Aubrey disguises Surprise as a whaling ship; he hopes the French will be lured in to capture the valuable ship rather than destroy it. Acheron falls for the disguise and Surprise launches her attack. With the back wheels of the cannons taken off, the cannons are able to fire upon Acheron's mainmast while Captain Howard's Marine sharpshooters pick off the crew of Acheron from above. Acheron is disabled when the mainmast snaps and falls into the sea. Aubrey leads boarding parties, engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Upon capturing the ship, Aubrey is informed by the ship's doctor that the French captain is dead and is given the Captain's sword.

Acheron and Surprise are repaired; while Surprise remains in the Galapagos, the captured Acheron is to be taken to Valparaíso. As Acheron sails away, Maturin mentions that their doctor had died months ago. Realising the French captain deceived him by pretending to be the ship's doctor, Aubrey gives the order to change course to intercept Acheron and escort her to Valparaíso, and for the crew to assume battle stations. Maturin is once again denied the chance to explore the Galapagos, but Aubrey wryly notes that since the bird he seeks is flightless, "it's not going anywhere", and the two play Musica notturna delle strade di Madrid by Luigi Boccherini as Surprise turns in pursuit of Acheron once more.

Cast

|

Commissioned Officers

Warrant and Standing Officers

|

HMS Surprise's Crew

Other

|

Production

Development

The film is drawn from the Aubrey-Maturin novels by Patrick O'Brian, but matches the events in no one novel. The author drew from real events in the Napoleonic Wars, as he describes in the introduction to the first novel, Master and Commander. Many have speculated on which Royal Navy captain matches the fictional character most.[4] The Royal Navy Museum considers Captain Lord Cochrane as the inspiration for the character in the first novel, Master and Commander.[5]

No specific real life captain completely matches Aubrey, but the exploits of two naval captains inspired events in the novels, Captain Thomas Cochrane, and Captain William Woolsey. Cochrane used the ruse of placing a light on a floating barrel at night to avoid capture.[6] Woolsey, aboard HMS Papillon, disguised a ship under his command as a commercial boat; on discovering information that a rogue ship was on the other side of a small island, he sailed around the island and captured the Spanish ship by stratagem, on April 15, 1805.[7]

The film combines elements from 13 different novels of Patrick O'Brian, but the basic plot mostly comes from The Far Side of the World. However, in the film version, the action takes place in 1805, during the Napoleonic wars, instead of 1813 during the Anglo-American War of 1812, as the producers wished to avoid offending American audiences.[8] In consequence, the fictional opponent was changed from the USS Norfolk to the French privateer frigate Acheron. Acheron in the film was reconstructed by the film's special-effects team who took stem-to-stern digital scans of USS Constitution at her berth in Boston, from which the computer model of Acheron was rendered.[9] The stern chase around Cape Horn is taken from the novel Desolation Island, although the Acheron replaced the Dutch 74-gun warship Waakzaamheid, the Surprise replaced the Leopard, and in the book it is Aubrey who is being pursued around the Cape of Good Hope.

The episode in which Aubrey deceives the enemy by means of a raft bearing lanterns is taken from Master and Commander, and the episode in which Maturin directs the surgery on himself, while gritting his teeth in pain, to remove a bullet is taken from HMS Surprise.[10] Other incidents in the film come from other books in O'Brian's series.

The film's special edition DVD release contains behind-the-scenes material that give insights into the film-making process. Great efforts were made to reproduce the authentic look and feel of life aboard an early nineteenth-century man-of-war. However, only ten days of the filming actually took place at sea on board Rose (a reproduction of the 18th-century post ship HMS Rose), while other scenes were shot on a full-scale replica mounted on gimbals in a large tank at Baja Studios. The Rose is now renamed HMS Surprise in honor of her movie role; she is moored at the San Diego Maritime Museum and serves as a dockside attraction (and in September 2007 was returned to sailing status). There was a third HMS Surprise which was a scale model built by Weta Workshop. A storm sequence was enhanced using digitally-composited footage of waves actually shot on board a modern replica of Cook's Endeavour rounding Cape Horn. All of the actors were given a thorough grounding in the naval life of the period in order to make their performances as authentic as possible. The ship's boats used in the film were Russian Naval six- and four-oared yawls supplied by Central Coast Charters and Boat Base Monterey. Their faithful 18th-century appearance complemented the historical accuracy of the rebuilt "Rose," whose own boat, the "Thorn," could be used only in the Brazilian scene. The on-location shots of the Galapagos were unique for a feature film as normally only documentaries are filmed on the islands.

Richard Tognetti, who scored the film's music, taught Crowe how to play the violin, as Aubrey plays the violin with Maturin on his cello in the movie.[11] Crowe purchased the violin personally as the budget did not allow for the expense. The violin was made in 1890 by the Italian violin maker Leandro Bisiach, and sold at auction in 2018 for US$104,000.[12] Bettany learned how to play the cello for the role of Maturin, so the pair could be filmed playing properly. The recording was dubbed in the final version of the film.[13]

Sound

Sound designer Richard King earned Master and Commander an Oscar for its sound effects by going to great lengths to record realistic sounds, particularly for the battle scenes and the storm scenes.[14] King and director Peter Weir began by spending months reading the Patrick O'Brian novels in search of descriptions of the sounds that would have been heard on board the ship—for example, the "screeching bellow" of cannon fire and the "deep howl" of a cannonball passing overhead.[14]

King worked with the film's Lead Historical Consultant Gordon Laco, who located collectors in Michigan who owned a 24-pounder and a 12-pounder cannon. King, Laco, and two assistants went to Michigan and recorded the sounds of the cannon firing at a nearby National Guard base. They placed microphones near the cannon to get the "crack" of the cannon fire, and also about 300 yards (270 m) downrange to record the "shrieking" of the chain shot as it passed overhead. They also recorded the sounds of bar shot and grape shot passing overhead, and later mixed the sounds of all three types of shot for the battle scenes.

For the sounds of the shot hitting the ships, they set up wooden targets at the artillery range and blasted them with the cannon, but found the sonic results underwhelming. Instead, they returned to Los Angeles and there recorded sounds of wooden barrels being destroyed. King sometimes added the "crack" of a rifle shot to punctuate the sound of a cannonball hitting a ship's hull.[14]

For the sound of wind in the storm as the ship rounds Cape Horn, King devised a wooden frame rigged with one thousand feet of line and set it in the back of a pickup truck. By driving the truck at 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) into a 30–40-knot (56–74 km/h; 35–46 mph) wind, and modulating the wind with barbecue and refrigerator grills, King was able to create a range of sounds, from "shrieking" to "whistling" to "sighing," simulating the sounds of wind passing through the ship's rigging.

Music

Iva Davies, lead singer of the Australian band Icehouse, traveled to Los Angeles to record the soundtrack to the film with Christopher Gordon and Richard Tognetti. Together, they won the 2004 APRA/AGSC Screen Music Award in the "Best Soundtrack Album" category.[15] The score includes an assortment of baroque and classical music, notably the first of Johann Sebastian Bach's Suites for Unaccompanied Cello, Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007, played by Yo-Yo Ma; the Strassburg theme in the third movement of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Violin Concerto No. 3; the third (Adagio) movement of Corelli's Christmas Concerto (Concerto grosso in G minor, Op. 6, No. 8); and a recurring rendition of Ralph Vaughan Williams's Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis. The music played on cello before the end is Luigi Boccherini's String Quintet (Quintettino) for 2 violins, viola & 2 cellos in C major ("Musica notturna delle strade di Madrid"), G. 324 Op. 30. The two arrangements of this cue contained in the CD differ significantly from the one heard in the movie.

The song sung in the wardroom is "Don't Forget Your Old Shipmates”, a British Navy song written in the early 1800s and arranged in 1978 by Jim Mageean[16] from his album 'Of Ships... and Men.'[17] The tunes sung and played by the crew on deck at night are "O'Sullivan's March", "Spanish Ladies" and "The British Tars" ("The shipwrecked tar"), which was set to tune of "Bonnie Ship the Diamond" and called "Raging Sea/Bonnie Ship the Diamond" on the soundtrack.

Track listing

| No. | Title | Composer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Far Side of the World" | Christopher Gordon | 9:17 |

| 2. | "Into the Fog" | Christopher Gordon | 2:11 |

| 3. | "Violin Concerto No. 3 - Rondeau" | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | 1:18 |

| 4. | "The Cuckold Comes out of the Amery" | Traditional | 3:26 |

| 5. | "Smoke n'oakum" | Christopher Gordon | 5:25 |

| 6. | "Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis" | Ralph Vaughan Williams | 5:10 |

| 7. | "Concerto grosso n°8, op. 6 - Adagio" | Arcangelo Corelli | 1:55 |

| 8. | "The Doldrums" | Christopher Gordon | 2:45 |

| 9. | "Suite No.1 in G major - Prelude" | Johann Sebastian Bach | 2:28 |

| 10. | "The Galapagos" | Christopher Gordon | 1:38 |

| 11. | "Folk Medley" | Traditional | 5:10 |

| 12. | "The Phasmid" | Christopher Gordon | 2:34 |

| 13. | "The Battle" | Christopher Gordon | 5:04 |

| 14. | "Quintette op. 30 n°6 – Passa Calle (Allegro vivo) (Musica notturna delle strade di Madrid)" | Luigi Boccherini | 9:21 |

| 15. | "Full Circle" | Christopher Gordon | 1:34 |

Release

Box office

Master and Commander opened #2 in the first weekend of North American release, November 14–16, 2003, earning $25,105,990. It dropped to the #4 position in the second weekend and #6 in the third, and finished the domestic run with $93,927,920 in gross receipts. Outside the U.S. and Canada, the film grossed $118,083,191, doing best in Italy (at $15,111,841) with an overall worldwide total of $212,011,111.[3]

Critical response

The film was critically well received, as 85% of 213 reviews tallied by the aggregate web site Rotten Tomatoes gave the film an overall positive rating, with an average rating of 7.62/10. The site's consensus states: "Russell Crowe's rough charm is put to good use in this masterful adaptation of Patrick O'Brian's novel."[18] On Metacritic, the film has an 81 out of 100 rating based on 42 critics, indicating "universal acclaim". However, the Metacritic “User Score” is considerably less positive, ranking 6.4 out of 10.[19]

Roger Ebert gave the film 4 stars out of 4, saying that "it achieves the epic without losing sight of the human".[20]

Christopher Hitchens gave a mixed review: "Any cinematic adaptation of O'Brian must stand or fall by its success in representing this figure [Dr. Stephen Maturin]. On this the film doesn't even fall, let alone stand. It skips the whole project." (The film omits completely the fact that he is a spy as well as doctor and naturalist – a key plot element in the novels.) Hitchens nonetheless praised the action scenes, writing: "In one respect the action lives up to its fictional and actual inspiration. This was the age of Bligh and Cook and of voyages of discovery as well as conquest, and when HMS Surprise makes landfall in the Galapagos Islands we get a beautifully filmed sequence about how the dawn of scientific enlightenment might have felt."[21]

San Francisco Chronicle film reviewer Mick LaSalle was generally downbeat and, after praising director Weir's handling of scenes with no dialog, observed that “Weir is less surefooted as a screenwriter. Having not read any of O'Brian's novels, I can't say if the fault is in Weir's adaptation or in the source material, but halfway into "Master and Commander," the friendship of the captain and the doctor begins to seem schematic, as if all the positive traits that an individual could have were divided equally between these two guys, just so they can argue. Their interaction takes on a preening quality, reminiscent of the interaction of the "Star Trek" characters four or five movies down the line. We come to realize that the specific adventure matters little except as a showcase for these personalities. Once that happens, the story involving the French ship loses much of its interest and all of its danger, and the movie starts taking on water. "Master and Commander" stays afloat to the finish, but that's all that can be said.[22]

Awards and honors

This film was nominated for awards in many categories of annual movie competitions. It won many of those award categories, as fully listed in the main article on the accolades won by this movie. A few highlights are listed here.

- Won, Academy Award for Best Cinematography — Russell Boyd

- Won, Academy Award for Best Sound Editing — Richard King

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Picture — Samuel Goldwyn, Jr., Peter Weir and Duncan Henderson, producers

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Director — Peter Weir

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Art Direction — Art Direction: William Sandell; Set Decoration: Robert Gould

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Costume Design — Wendy Stites

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Film Editing — Lee Smith

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Makeup — Edouard Henriques III and Yolanda Toussieng

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Sound Mixing — Paul Massey, Doug Hemphill and Art Rochester

- Nominated, Academy Award for Best Visual Effects — Dan Sudick, Stefen Fangmeier, Nathan McGuinness and Robert Stromberg

Peter Weir won the BAFTA award for best direction in 2004 for this film.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Epic Film[24]

Possible sequel

Director Weir, asked in 2005 if he would make a sequel, stated he thought it "most unlikely", and after disclaiming internet rumors to the contrary, stated "I think that while it did well...ish at the box office, it didn't generate that monstrous, rapid income that provokes a sequel."[25] In 2007 the film was included on a list of "13 Failed Attempts To Start Film Franchises" by The A.V. Club, noting that "...this surely stands as one of the most exciting opening salvos in nonexistent-series history, and the Aubrey-Maturin novels remain untapped cinematic ground."[26]

In December 2010, Crowe launched an appeal on Twitter to get the sequel made: "If you want a Master and Commander sequel I suggest you e-mail Tom Rothman at Fox and let him know your thoughts".[27]

As of May 2019, there have been no further updates regarding this possible film. Film critic Scott Tobias wrote a positive retrospective article about this film in 2019, begrudging the fact that Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, another sea-faring film also released in 2003, had led to a string of Pirates of the Caribbean fantasy films, but there was no demand for a sequel featuring Captain Jack Aubrey and deeply rooted in historical facts of the Napoleonic Wars, the Age of Sail and the Age of Discovery.[28]

Notes

- 20th Century Fox involved Miramax Films and Universal Pictures to co-finance and co-produce the film, but Fox itself distributed the film.[1]

References

- Staff (August 14, 2003). "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- "MASTER AND COMMANDER – THE FAR SIDE OF THE WORLD (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. October 28, 2003. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- "Box Office History". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- Cordingly, David (September 2, 2007). "The real master and commander". The Telegraph. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Thomas Cochrane". Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, Royals Museums. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- Cochrane, Thomas, Earl of Dundonald (1860). The Autobiography of a Seaman. I. London: Richard Bentley. p. 107.

- James, William I (1837). The Naval History of Great Britain from the Declaration of War by France in 1793 to the Accession of George IV. 4 (New ed.). Bentley. pp. 132–133. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "The British Navy Sails again in "Master and Commander"". www.stfrancis.edu. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Hendrix, Steve (November 16, 2003). "Now Playing at a Theater Near You: Old Ironsides". The Washington Post. Retrieved on 25 August 2009.

- HMS Surprise, Patrick O'Brian, 1973, UK, Collins (ISBN 0002213168)

- Chenery, Susan (March 30, 2019). "Against the tide". The Weekend Australian. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- "Movie Star Russell Crowe's Violin Has Sold at Auction for $104,000". Classical Music News. April 8, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Trivia: Master and Commander". TV Tropes. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ""The Sounds of Realism in 'Master and Commander'" - National Public Radio interview with Richard King". Npr.org. November 13, 2003. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- "2004 Winner Best Soundtrack Album – Screen Music Awards". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- Bryant, Jerry (June 11, 2010). ""Long we've toiled on the rolling wave": One sea song's journey from the gun deck to Hollywood". Music of the Sea Symposium. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- "Jim Mageean – Of Ships...And Men". Discogs. 1978. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

Click More Info to see Average Rating

- "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Hitchens, Christopher (November 14, 2003). "Empire Falls – How Master and Commander gets Patrick O'Brian wrong". Slate. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- LaSalle, Mick (November 14, 2003). "Grab your breeches, hoist the mainsail and prepare for an epic ride -- but is 'Master and Commander' seaworthy?". SFGate.com. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "The 76th Academy Awards (2004) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Rahner, Mark (August 30, 2005). "What hath Peter Weir wrought?". Seattle Times. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- Bowman, Donna; Noel Murray; Sean O'Neal; Keith Phipps; Nathan Rabin; Tasha Robinson (April 30, 2007). "Inventory: 13 Failed Attempts To Start Film Franchises". The A.V. Club. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- Crowe, Russell (December 6, 2010). "If you want a Master and Commander sequel I suggest you e-mail Tom Rothman at Fox and let him know your thoughts".

- Tobias, Scott (January 4, 2019). "Revisiting Hours: Ships Ahoy — 'Master and Commander'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

Bibliography

- McGregor, Tom (2003). The Making of Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05865-4.

- Tibbetts, John C.; Welsh, James M., eds. (2005). "The Far Side of the World (Master and Commander)". The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (Second ed.). Facts on File. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-0816054497.

See also

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. |

- A Literary Companion to the Film which explores the film's connections to the Aubrey Maturin series

- Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World on IMDb

- Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World at Box Office Mojo

- Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World at Rotten Tomatoes

- Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World at Metacritic

- Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World at the Wayback Machine (archived August 1, 2003)