Picnic at Hanging Rock (film)

Picnic at Hanging Rock is a 1975 Australian mystery drama film which was produced by Hal and Jim McElroy, directed by Peter Weir, and starred Rachel Roberts, Dominic Guard, Helen Morse, Vivean Gray and Jacki Weaver. It was adapted by Cliff Green from the 1967 novel of the same name by Joan Lindsay, who was deliberately ambiguous about whether the events really took place, although the story is entirely fictitious.

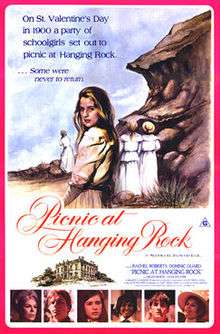

| Picnic at Hanging Rock | |

|---|---|

Original 1975 Australian theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Weir |

| Produced by | Hal McElroy Jim McElroy |

| Screenplay by | Cliff Green |

| Based on | Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Russell Boyd |

| Edited by | Max Lemon |

Production company | British Empire Films South Australian Film Corporation Australian Film Commission McElroy & McElroy Picnic Productions |

| Distributed by | British Empire Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | AU$443,000[1] |

| Box office | AU$5,120,000 (Aust) |

The plot involves the disappearance of several schoolgirls and their teacher during a picnic at Hanging Rock, Victoria, on Valentine's Day in 1900, and the subsequent effect on the local community. Picnic at Hanging Rock was a commercial and critical success, and helped draw international attention to the then-emerging Australian New Wave of cinema.

Plot

At Appleyard College, a girls' private school near the town of Woodend, Victoria, Australia, the students are dressing on the morning of Valentine's Day, 1900. Miranda, Irma, Marion, Rosamund, Sara, and outsider Edith read poetry and Valentine's Day cards.

The group prepares for a picnic to a local geological formation known as Hanging Rock, accompanied by the mathematics mistress Miss Greta McCraw and the young and beautiful Mlle. de Poitiers. On the command of the stern headmistress Mrs. Appleyard, jittery teacher Miss Lumley advises orphan student Sara that she is not allowed to attend.

Buggy operator Ben Hussey gets the group to the Rock by mid-afternoon. After a meal, Mr Hussey notes his watch has stopped at the stroke of twelve, as has the watch of Miss McCraw. With permission from Mlle. de Poitiers, Miranda, Marion and Irma decide to explore Hanging Rock and take measurements, with Edith allowed to follow. The group is observed several minutes later by a young Englishman, Michael Fitzhubert, who is lunching at the Rock with his uncle Colonel Fitzhubert, aunt Mrs. Fitzhubert, and valet Albert. Near the top of Hanging Rock, the group lies down, apparently dazed by the sun. Miss McCraw, at the base of the Rock, stares up. Miranda, Marion, and Irma awaken and, as if in a trance, move into a recess in the rock face. Edith, witnessing this, screams and flees down the Rock in terror.

The distraught and hysterical party eventually returns to the College, where Mlle. de Poitiers explains to Mrs Appleyard that Miss McCraw has been left behind. Sara notes the absence of Miranda; and Mr. Hussey explains to Mrs Appleyard that Miranda, Irma, Marion, and Miss McCraw went missing. A search party, led by Sgt. Bumpher and Constable Jones of the local police, finds nothing, although Edith reveals that she witnessed Miss McCraw climbing the Rock without her skirt. Michael Fitzhubert is questioned and reveals that he watched the schoolgirls, but can provide no clues as to their whereabouts.

Michael becomes obsessed with finding Miranda; and, with Albert, he conducts another search of Hanging Rock. Despite Albert's protests, Michael decides to remain overnight and begins climbing again the next day, leaving a trail of paper. When Albert follows the markers, he finds a nearly catatonic Michael. Michael passes Albert a fragment of lace from a dress, before departing to town. Albert returns to Hanging Rock and discovers an unconscious Irma. The residents of Woodend become restless as news of the discovery spreads. Mrs Appleyard advises Miss Lumley that several parents have withdrawn their children from the school. At the Fitzhubert home, where Irma is treated for dehydration, the doctor's examination shows only cuts on her hands and broken fingernails; he affirms she has not been molested. When she awakens, Irma tells the police and Mlle. de Poitiers she has no memory of what happened. A servant girl notes that Irma's corset is missing. Michael befriends the recovered Irma but alienates her when he demands to know what happened on the Rock. Before leaving for Europe, Irma visits her classmates a final time; they become hysterical and demand to know what happened to Miranda and Marion. Irma flees, briefly noticing Sara strapped to a wall, meant by Miss Lumley to correct Sara's posture. That night, Miss Lumley gives notice to a drunken Mrs Appleyard that she is resigning.

Mrs Appleyard tells Sara that, as her guardian has not paid her tuition, Sara must return to the orphanage. The next day, Michael tells Albert he has decided to travel north, with Albert revealing he had a dream in which his lost sister Sara visited him. Meanwhile, Mrs Appleyard lies to Mlle. de Poitiers and claims that Sara's guardian picked her up, as all the students depart for their holiday. The next morning, Sara's body is found in the greenhouse by Mr. Whitehead, the school gardener. Believing Sara committed suicide by leaping from her bedroom window, Whitehead informs Mrs. Appleyard, who is disturbingly calm in full mourning dress with her possessions packed.

During a flashback to the picnic scene, Sgt. Bumpher states in a voice over that the body of Mrs Appleyard was found at the base of Hanging Rock from an apparent suicide. The search for the two schoolgirls and Miss McCraw continued sporadically for several years without success, remaining an unsolved mystery.

Cast

- Rachel Roberts as Mrs. Appleyard

- Dominic Guard as Michael Fitzhubert

- Helen Morse as Mlle. de Poitiers

- Anne-Louise Lambert as Miranda St. Clare

- Margaret Nelson as Sara Waybourne

- John Jarratt as Albert Crundall

- Wyn Roberts as Sgt. Bumpher

- Karen Robson as Irma Leopold

- Christine Schuler as Edith Horton

- Jane Vallis as Marion Quade

- Vivean Gray as Miss McCraw

- Martin Vaughan as Ben Hussey

- Kirsty Child as Miss Lumley

- Jacki Weaver as Minnie

- Frank Gunnell as Mr. Whitehead

- Tony Llewellyn-Jones as Tom

- John Fegan as Doc. McKenzie

- Kay Taylor as Mrs Bumpher

- Peter Collingwood as Col. Fitzhubert

- Garry McDonald as Const. Jones

- Olga Dickie as Mrs. Fitzhubert

- Jenny Lovell as Blanche

Production

The novel was published in 1967. Reading it four years later, Patricia Lovell thought it would make a great film. She did not originally think of producing it herself until Phillip Adams suggested she try it; she optioned the film rights in 1973, paying $100 for three months.[3] She hired Peter Weir to direct on the basis of Homesdale and Weir brought in Hal and Jim McElroy to help produce.[1]

Screenwriter David Williamson was originally chosen to adapt the film, but was unavailable and recommended noted TV writer Cliff Green.[4] Joan Lindsay had approval over who did the adaptation and she gave it to Green, whose first draft Lovell says was "excellent".[3]

The finalised budget was A$440,000, coming from the Australian Film Development Corporation, British Empire Films and the South Australian Film Corporation. $3,000 came from private investors.[3]

Filming

Filming began in February 1975 with principal photography taking six weeks.[5][6] Locations included Hanging Rock in Victoria, Martindale Hall near Mintaro in rural South Australia, and at the studio of the South Australian Film Corporation in Adelaide.

To achieve the look of an Impressionist painting for the film, director Weir and director of cinematography Russell Boyd were inspired by the work of British photographer and film director David Hamilton, who had draped different types of veils over his camera lens to produce diffused and soft-focus images.[6] Boyd created the ethereal, dreamy look of many scenes by placing simple bridal veil fabric of various thicknesses over his camera lens.[4][6] The film was edited by Max Lemon.

Casting

Weir originally cast Ingrid Mason as Miranda, but realised after several weeks of rehearsals that it was "not working" and cast Anne-Louise Lambert. Mason was persuaded to remain in the role of a minor character by producer Patricia Lovell.[4] The role of Mrs. Appleyard was originally to have been taken by Vivien Merchant; Merchant fell ill and Rachel Roberts was cast at short notice.[1] Several of the schoolgirls' voices were dubbed in secret by professional voice actors, as Weir had cast the young actresses for their innocent appearance rather than their acting ability.[7] The voice actors were not credited, although more than three decades later, actress Barbara Llewellyn revealed that she had provided the voice for all the dialogue of Edith (Christine Schuler, now Christine Lawrance).[7][8]

Music

The main title music was derived from two traditional Romanian panpipe pieces: "Doina: Sus Pe Culmea Dealului" and "Doina Lui Petru Unc" with Romanian Gheorghe Zamfir playing the panpipe (or panflute) and Swiss born Marcel Cellier the organ. Australian composer Bruce Smeaton also provided several original compositions (The Ascent Music and The Rock) written for the film.[4]

Other classical additions included Bach's Prelude No. 1 in C from The Well-Tempered Clavier performed by Jenő Jandó; the Romance movement from Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik; the Andante Cantabile movement from Tchaikovsky's String Quartet No. 1, Op. 11, and the Adagio un poco mosso from Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 "Emperor" performed by István Antal with the Hungarian State Symphony Orchestra. Traditional British songs God Save the Queen and Men of Harlech also appear.

There is currently no official soundtrack commercially available. In 1976, CBS released a vinyl LP titled "A Theme from Picnic at Hanging Rock", a track of the same name and "Miranda's Theme". A 7" single was released in 1976 of the Picnic At Hanging Rock theme by the Nolan-Buddle Quartet. David Appleyard's cover of Bruce Smeaton's "Picnic At Hanging Rock: The Ascent Music" was released in 2018.

Release

The film premiered on August 8, 1975, at the Hindley Cinema Complex in Adelaide. It was well-received by audiences and critics alike.[6]

Reception

Vincent Canby, writing about the film for The New York Times[9]

Weir recalled that when the film was first screened in the United States, American audiences were disturbed by the fact that the mystery remained unsolved. According to Weir, "One distributor threw his coffee cup at the screen at the end of it, because he'd wasted two hours of his life—a mystery without a goddamn solution!"[4] Critic Vincent Canby noted this reaction among audiences in a 1979 review of the film, in which he discussed the film's elements of artistic "Australian horror romance", albeit one without the cliches of a conventional horror film.[9]

Despite this, the film was a critical success, with American film critic Roger Ebert calling it "a film of haunting mystery and buried sexual hysteria" and remarked that it "employs two of the hallmarks of modern Australian films: beautiful cinematography and stories about the chasm between settlers from Europe and the mysteries of their ancient new home."[10]

Cliff Green stated in interview that "Writing the film and later through its production, did I—or anyone else—predict that it would become Australia's most loved movie? We always knew it was going to be good—but that good? How could we?"[5]

Picnic at Hanging Rock currently has an approval rating of 90% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 40 reviews, with an average rating of 8.42/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Visually mesmerizing, Picnic at Hanging Rock is moody, unsettling, and enigmatic -- a masterpiece of Australian cinema and a major early triumph for director Peter Weir".[11] Metacritic, another review aggregator, gives the film a score of 81/100 based on 15 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[12]

Box office

Picnic at Hanging Rock grossed $5,120,000 in box office sales in Australia.[13] This is equivalent to approximately $23,269,160 in 2016 Australian dollars.[14]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| AACTA Award | Best Film | Hal and Jim McElroy | Nominated |

| Best Direction | Peter Weir | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Helen Morse | Nominated | |

| British Society of Cinematographer Award | Best Cinematography | Russell Boyd | Nominated |

| BAFTA Award | Best Cinematography | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Judith Dorsman | Nominated | |

| Best Soundtrack | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Award | Best Writing | Cliff Green | Nominated |

Versions

Picnic at Hanging Rock was first released on DVD in the Criterion Collection on 3 November 1998. This release featured a director's cut of the film with an entirely new transfer, a theatrical trailer and liner notes about the film. The same year, the film was also re-released theatrically, with Weir removing seven minutes from the film that apparently detracted from the narrative.[4] The Criterion Collection re-released the director's cut on Blu-ray on June 17, 2014. It includes a paperback copy of the novel and many supplemental features, most of which are not available on international releases.

The film was later released in a special 3-disc set on 30 June 2008 in the United Kingdom. This set included the director's cut and a longer original version, interviews with filmmakers and book author Joan Lindsay, poster and still galleries, a 120-minute documentary and deleted scenes. UK distributor Second Sights Films also released the film on Blu-ray on 26 July 2010.[15][16]

In Australia it was released on DVD by Umbrella Entertainment in August 2007, and re-released in a 2-disc Collector's Edition in May 2011. This edition includes special features such as the various theatrical trailers, poster and still galleries, documentaries and interviews with cast, crew and Joan Lindsay.[17] It was released on Blu-ray by Umbrella Entertainment with a newly restored print, the feature-length documentary A Dream Within A Dream, a 25-minute on-set documentary, A Recollection: Hanging Rock 1900 and the theatrical trailer on 12 May 2010.[18]

Legacy and influence

The film has gone on to inspire other more recent artists, who have come to regard the film for its themes as well as its unique visuals.

Director Sofia Coppola has borrowed heavily from Picnic at Hanging Rock for her productions of The Virgin Suicides and Marie Antoinette.[19] Both films, like Picnic at Hanging Rock, deal extensively with themes of death and femininity as well as adolescent perceptions of love and sexuality.[20][21]

Excerpts of the film's dialogue can be heard in the cello rock group Rasputina's song "Girls' School" which is featured on their album Frustration Plantation.[22][23] Rasputina's personal aesthetic has also been likened to Picnic at Hanging Rock by critics.[24]

American actress Chloë Sevigny has cited the film as an influence on her personal style.[25]

American television writer Damon Lindelof said that the film was an influence on the second season of the television show The Leftovers.[26]

References

- David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, 1980 p68-69

- Rayner, Jonathan. The Films of Peter Weir. London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003. ISBN 0826419089, pp. 70–71

- Scotty Murray & Antony I Ginanne, "Producing 'Picnic': Pat Lovell", Cinema Papers, March–April 1976 p298-301

- "A Dream Within a Dream": Documentary (120 min, Umbrella Entertainment, 2004)

- "The Vault", Storyline, Australian Writers Guild, 2011, p. 68

- McCulloch, Janelle (30 March 2017). "The extraordinary story behind Picnic at Hanging Rock". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Picnic at Hanging Rock - The Unseen Voices". The Bright Light Cafe. 2012.

- Buckmaster, Luke (23 January 2014). "Picnic at Hanging Rock: Rewatching classic Australian films". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "Picnic at Hanging Rock by Vincent Canby". The Criterion Collection. 1979. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (2 August 1998). "Picnic at Hanging Rock". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Picnic at Hanging Rock Reviews". Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Australian Films at the Australian Box Office" (PDF). Film Victoria. p. 2. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Inflation Calculator". Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Picnic At Hanging Rock - The Director's Cut [Blu-ray] [1975]". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- Atanasov, Svet (14 August 2010). "Picnic at Hanging Rock Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com.

- "Umbrella Entertainment - Collector's Edition". Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- "Picnic At Hanging Rock Blu-ray". Umbrella Entertainment Website. Umbrella Entertainment. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Weird, Jake. "The Virgin Suicides and Picnic at Hanging Rock". Weirdland. BlogSpot. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Monden, Masafumi (2013). "Contemplating in a dream-like room and the aesthetic imagination of girlhood". Film, Fashion & Consumption. 2 (2). Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Rodenstein, Roy. "The Virgin Suicides". The Tech Online. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Creager, Melora (2004). Frustration Plantation. New York City: Instinct Records.

- Creager, Melora. "Were the background voices in "Girls' School"..." FanBridge. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Thill, Scott. "Rasputina's Cabin Fever". Morphizm. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Muhlke, Christine. "Profile In Style: Chloë Sevigny". New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Ryan, Maureen. "'The Leftovers' Boss Damon Lindelof Explains That Shocking Twist". Variety. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

External links

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Picnic at Hanging Rock (film) |

- Picnic at Hanging Rock on IMDb

- Picnic at Hanging Rock at AllMovie

- Picnic at Hanging Rock at Oz Movies

- "Picnic at Hanging Rock Locations" Field guide to the locations used for filming at Hanging Rock, Victoria, Australia

- Picnic at Hanging Rock: What We See and What We Seem an essay by Megan Abbott at the Criterion Collection