Latin American Spring

The Latin American Spring (Spanish: Primavera Latinoamericana) is a series of protests, uprisings and rebellions referred to as spring that began in the mid-2010s throughout Latin America.[1][2][3] Since at least 2015, anti-corruption protest movements have remained popular throughout Latin America.[4] The series of protests occurred in two waves; the first beginning in 2015 were mainly anti-establishment demonstrations while the second wave beginning in 2018 were more targeted against corrupt institutions or individuals.[4]

| Latin American Spring | |

|---|---|

| Primavera Latinoamericana (Spanish) | |

| |

| Date | 12 February 2014 – ongoing (6 years, 4 months, 2 weeks and 2 days) |

| Location | |

| Caused by |

|

| Goals |

|

| Resulted in | Results by country

|

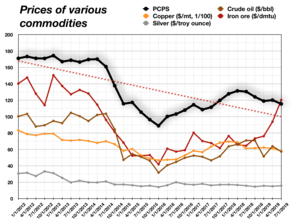

The crises in the region occurred following the end of the 2000s commodities boom, with an economic downturn and slow growth occurring throughout the 2010s.[5] Both left and right-wing governments faced a recently-grown middle class produced from the economic boom that turned to protest as a result of years of corruption, economic hardship and increasing inequality.[6]

Background

Pink tide and commodities boom

The third wave of democratization in the 1980s, granted leftist parties to become electorally viable, with the United States reducing its opposition to such parties following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[7] In the 1990s, neoliberal policies resulted in less social spending, unemployment, inflation and inequality.[8] Beginning in the 2000s, Latin Americans turned away from neoliberal policies and elected leftist leaders, who had recently turned toward more democratic processes instead of armed actions.[9]

Leftist leaders were elected throughout the region in a movement described as the "pink tide", with their governments relying on the 2000s commodities boom to initiate populist policies for support.[10][11] China, which was experiencing a growing economy simultaneously with Latin America, took advantage of strained relations between the United States and leftist governments in Latin America, partnering with regional governments.[10][12] South America in particular initially saw a drop in inequality and a growth in its economy as a result of Chinese commodity trade.[12] According to Daniel Lansberg, such policies resulted in "high public expectations in regard to continuing economic growth, subsidies, and social services".[11]

End of boom

Commodity prices lowered into the 2010s and overspending by pink tide governments led to unsustainable policies, with supporters becoming disenchanted, eventually leading to the rejection of leftist governments.[11][13] By the mid-2010s, Chinese investment in Latin America had also begun to decline.[12] Analysts state that such unsustainable policies were more apparent in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela,[13][12] which received Chinese funds without any oversight.[12][14] The International Monetary Fund stated that between 2009 and 2019, national debt in South America increased from 51.2% to 78.1%.[15]

The end of the boom left regional governments with a difficult decision; siding with potential investors and lenders calling for austerity measures or the populace which rejected austerity, arguing that it did not improve social and inequality concerns.[15] As a result, some scholars have stated that rise and fall of regional governments were "a byproduct of the commodity cycle's acceleration and decadence".[10]

Timeline

First wave: anti-establishment protests

2014

As the result of the end of the commodities boom, unsustainable economic policies of late-president Hugo Chávez left the economy of Venezuela in crisis.[13][16][17] Issues with corruption[18] and crime in Venezuela[19] had also led to increased discontent among the Venezuelan populace. On 12 February 2014, protests against Chávez's successor, Nicolás Maduro, began the 2014 Venezuelan protests. The movement developed rapidly and was quickly compared to the Arab Spring. The International Business Times penned "For many analysts and international activists, the closest match to what Venezuela is going through occurred three years ago and a continent away: the Arab Spring",[20] Agence France-Presse wrote that protests "evoked some scenes of the 'Arab spring'"[21] and even President Maduro stated "They are trying to sell to the world the idea that the protests are some of sort of Arab spring", alleging a conspiracy was formulated by his opponents.[22] The protest moment has remained constant against Maduro since 2014.

2015

In Guatemala, a United Nations-led La Línea corruption case accused President Otto Pérez Molina of being involved in corrupt acts involving customs and smuggling in April 2015.[23] Subsequent protests in the country led to the resignation and arrest of Pérez Molina.[23] Protests against corruption began to intensify in countries neighboring Guatemala, with tens of thousands beginning protests in Nicaragua,[24][25] resulting in El Mundo writing that "[t]he American spring has triumphed in Guatemala with the resignation of its president, but this revolution has only just begun and promises to take hold in neighboring countries".[23]

Ecuador had seen years of increased funds during the commodities boom, but by 2015, the country saw its oil revenues drop by 50%.[26] The 2015 Ecuadorian protests began in June 2015 following introduction of austerity measures and inheritance tax proposals by President Rafael Correa.[26][27] Hundreds of thousands of protesters participated in the demonstrations in the following months.[28] Due to the rising disapproval of Correa, he passed a constitutional amendment to remove presidential term limits and removed himself from the 2017 Ecuadorian general election, with analysts suggesting that Correa would attempt to attain the presidency at a later date when the crisis stabilized.[27] Protests intensified later in the year after term limits were removed,[27] with presidential term limits eventually being reinstated following the 2018 Ecuadorian referendum and popular consultation.

By the end of 2015, some political analysts were already describing the occurrence of a "Latin American spring".[29][30][31] In September 2015, the Wilson Center outlined a scenario describing potential democratization mobilizations in Latin America, stating at the time that "[i]ncreased expectations of the rising middle classes generate impatience, dissatisfaction, and inability of citizens to identify themselves with politics. The 'Latin-American Spring' gains momentum as millions take to the streets, drawing on new technologies to organize".[30]

The Financial Times, discussing corruption and the rule of law in Latin America, wrote in December 2015:[31]

This new emphasis on the rule of law is a major shift for a continent where elites have long enjoyed impunity. It reflects an exploding desire among Latin American citizens for modern states that recognise the limits of power and respect constitutional checks and balances too. ... Popular revulsion with corruption, amplified by social media, is so widespread that some even talk about a “Latin American spring”.

In 2019, Americas Quarterly wrote, "Since 2015, anti-corruption protests have popped up almost everywhere in the region, converting law enforcement and judicial leaders into national celebrities. And there are no signs that social pressure is petering out".[4]

2016

The Odebrecht scandal resulted in widespread ramifications for Latin America, with anti-corruption protests gaining momentum in the region during the investigations.[4] Dissatisfaction with governments related to the Odebrecht scandal intensified in 2016, with more Latin Americans becoming disillusioned with democracy at the time, especially in countries more affected by the scandal.[5]

Millions of protesters mobilized in Brazil following the scandal,[32] with many Brazilians surveyed by the Latin American Public Opinion Project at the time believing that the majority of politicians in the country were involved in corruption.[5] President Dilma Rousseff was ultimately impeached following graft investigations related to Operation Car Wash.[33]

Following such demonstrations, Colombian businessman and diplomat Luis Alberto Moreno wrote in an article titled ¿Una primavera latinoamericana? that "throughout Latin America citizens are taking to the streets to say enough to corruption ... the demonstrations now involve a broad spectrum of society that includes, mainly, the emerging middle class of the region", with such popular pressure beginning to lead to the condemnation and arrest of many politicians in the region.[34]

Second wave: focused protests

2017

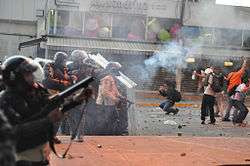

Protests began in January 2017 in Venezuela after the arrest of multiple opposition leaders and the cancellation of dialogue between the opposition and Nicolás Maduro's government. As the tension continued, the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis began in late March when the pro-Maduro Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) dissolved the opposition-led National Assembly, with the intensity of protests increasing greatly throughout Venezuela following the decision.[35][36][37] As April arrived, the protests grew "into the most combative since a wave of unrest in 2014" resulting from the crisis[38] with hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protesting daily through the month and into May.[39] After failing to prevent the July Constituent Assembly election, the opposition and protests largely lost momentum. Also in 2017, Peruvian former president Ollanta Humala and his wife were arrested after being involved in Operation Car Wash.

2018

The effects of the Odebrecht scandal also affected politics in Peru, with President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski becoming involved in an impeachment proceeding after being accused of accepting bribes from Odebrecht,[40] with Kuczynski later resigning following continued political pressure. Further instances of corruption led to thousands of Peruvians protesting, with the replacement president Martín Vizcarra demanding an opposition congress to approve a referendum with anti-corruption measures.[41] The 2018 Peruvian constitutional referendum would ultimately occur, with Transparency International praising the results, stating that "This is a very important opportunity, one that is unlike previous opportunities because, in part, the president appears genuinely committed".[42]

Nicaragua had major protests in 2018 against the policies of Daniel Ortega. Hundreds of people died in clashes against security forces.[43]

Characteristics

According to Brian Winter, policy vice president of the Americas Society/Council of the Americas, main characteristics of the movement are economic dissatisfaction following the commodities boom and the reliance on military might, with Winter saying that Latin Americans perceive that strongman politics leads to change.[5] Dr. Lupu of the Latin American Public Opinion Project agreed that as corruption and socioeconomic issues increased in Latin America, citizens turn towards strongmen and distanced themselves from supporting democracy.[5] Winter expressed concern with his assessment of Latin America in 2019, stating "My fear is that we’ve gone back to the battle days of coups and protests and instability ... I think all of these things play a role and the takeaway could be that we’re returning to a period ... where uprisings and coups and civil unrest were the rule of the day".[5]

See also

- Latin American protests (2019–present)

References

- Faiola, Anthony (14 November 2019). "How to make sense of the many protests raging across South America". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "With Juan Guaidó seizing the presidency, Venezuela's 'Latin Spring' is heating up". The Miami Herald. 23 January 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "How Latin America's uprisings could be good for copper and lithium". Stockhead. 28 October 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- February 5, Roberto Simon |; 2019. "The Changing Face of Anti-Corruption Protests in Latin America". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 2019-11-15.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "BNamericas: Brian Winter on Unrest in Latin America". Americas Society. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "Morales' Exit Stymies Comeback for Latin America's Left". The New York Times. 2019-11-12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Levitsky, Steven; Roberts, Kenneth. "The Resurgence of the Latin American Left" (PDF). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Rodriguez, Robert G. (2014). "Re-Assessing the Rise of the Latin American Left" (PDF). The Midsouth Political Science Review. Arkansas Political Science Association. 15 (1): 59. ISSN 2330-6882.

- Reid, Michael (September–October 2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94 (5): 45–53.

... half a dozen countries, led by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, formed a hard-left anti-American bloc with authoritarian tendencies...

- Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (Jan–Apr 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. 38 (1): 11–53.

The fate of Latin America's left turn has been closely associated with the commodities boom (or supercycle) of the 2000s, largely due to rising demand from emerging markets, notably China.

- Lansberg-Rodríguez, Daniel (Fall 2016). "Life after Populism? Reforms in the Wake of the Receding Pink Tide". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Georgetown University Press. 17 (2): 56–65.

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94 (5): 45–53.

As China industrialized in the first decade of the century, its demand for raw materials rose, pushing up the prices of South American minerals, fuels, and oilseeds. From 2000 to 2013, Chinese trade with Latin America rocketed from $12 billion to over $275 billion. ... Its loans have helped sustain leftist governments pursuing otherwise unsustainable policies in Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela, whose leaders welcomed Chinese aid as an alternative to the strict conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund or the financial markets. ... The Chinese-fueled commodity boom, which ended only recently, lifted Latin America to new heights. The region – and especially South America – enjoyed faster economic growth, a steep fall in poverty, a decline in extreme income inequality, and a swelling of the middle class.

- "Americas Economy: Is the "Pink Tide" Turning?". The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. 8 December 2015.

In 2004-13 many pink tide countries benefited from strong economic growth, with exceptionally high commodities prices driving exports, owing to robust demand from China. These conditions brought regional growth ... However, the negative impact of expansionary policy on inflation, fiscal deficits and non-commodity exports in many countries soon began to prove that this boom period was unsustainable, even before international oil prices plummeted alongside prices of other key commodities at the end of 2014. ... These challenging economic conditions have exposed the negative consequences of years of policy mismanagement in various countries, most notably in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela.

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues. Brookings Institution: 5–6.

[China] promised to impose no political conditions on its economic and technical assistance, in contrast to the usual strings-attached approach from Washington, Europe, and the international financial institutions, and committed to debt cancellation 'as China's ability permits.' ... As one South American diplomat put it, given the choice between the onerous conditions of the neoliberal Washington consensus and the no-strings-attached largesse of the Chinese, elevating relations with Beijing was a no-brainer.

- Spinetto, Juan Pablo (20 October 2019). "Political Risk Is Revived in Latin America as Protests Spread". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- Corrales, Javier (7 May 2015). "Don't Blame It On the Oil". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Siegel, Robert (25 December 2014). "For Venezuela, Drop In Global Oil Prices Could Be Catastrophic". NPR. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Democracy to the rescue?". Foreign Policy. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Rueda, Manuel. "How Did Venezuela Become So Violent?". Fusion. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Mallén, Patricia Rey (2014-04-05). "Is Venezuela The New Arab Spring? Why The Movement Resembles Egypt More Than Brazil". International Business Times. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "Estudiantes cumplen un mes de protestas en Caracas contra el gobierno de Maduro". Agence France-Presse (in Spanish). 2014-03-11. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Milne, Seumas; Watts, Jonathan (2014-04-08). "Venezuela protests are sign that US wants our oil, says Nicolás Maduro". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "El triunfo de la primavera americana". El Mundo (in Spanish). 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Wand, Alexander (14 June 2015). "Mass protests in Nicaragua as farmers claim planned canal will 'sell country to the Chinese'". The Independent. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Clashes erupt at Nicaragua electoral reform protests". Euronews. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Alvaro, Mercedes (25 June 2015). "Protesters in Ecuador Demonstrate Against Correa's Policies". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Collyns, Dan (2015-12-04). "Protests in Ecuador as lawmakers approve unlimited presidential terms". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- Morla, Rebeca (26 June 2015). "Correa Feels the Wrath of Massive Protests in Ecuador". PanAm Post. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Thofern, Uta (23 December 2015). "¿Primavera latinoamericana? ¡No, gracias! | DW | 23.12.2015". Deutsche Welle (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "Alerta Democrática: Four futures for democracy in Latin America 2030" (PDF). Wilson Center. 21 September 2015.

- "Los cambios políticos en Latinoamérica reflejan un rechazo a la corrupción, no a la ideología". Diario Libre (in Spanish). 29 December 2015. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "MAPA DAS MANIFESTAÇÕES CONTRA DILMA, 13/03". G1. 13 March 2016.

- Shoichet, Catherine E.; McKirdy, Euan. "Brazil's Senate ousts Rousseff in impeachment vote". CNN. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Moreno, Luis Alberto (2016-03-13). "¿Una primavera latinoamericana?, por Luis Alberto Moreno". El Comercio (Peru) (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "Venezuela accused of 'self-coup' after Supreme Court shuts down National Assembly". Buenos Aires Herald. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Venezuela's Descent Into Dictatorship". The New York Times. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Venezuela clashes 'self-inflicted coup': OAS". Sky News Australia. 1 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Goodman, Joshua (9 April 2017). "Venezuela's Maduro blasts foe for chemical attack comments". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- Dreier, Hannah (4 May 2017). "AP Explains: Venezuela's 'anti-capitalist' constitution". Yahoo News. Associated Press. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "Peru's leader faces impeachment". Bbc.com. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Sanchez, Mariana (29 July 2018). "Peru protests: President faces political crisis". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Tegel, Simeon (12 August 2018). "Corruption scandals have ensnared 3 Peruvian presidents. Now the whole political system could change". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Nicaragua unrest: What you should know". Al Jazeera. 17 Jul 2018. Retrieved 2019-11-28.