Operation Car Wash

Operation Car Wash (Portuguese: Operação Lava Jato) is an ongoing criminal investigation by the Federal Police of Brazil, Curitiba Branch. It began in March 2014 and was initially headed by investigative judge[lower-alpha 1] Sérgio Moro, and in 2019 by Judge Luiz Antônio Bonat.[13] It has resulted in more than a thousand warrants of various types. According to the Operation Car Wash task force, investigations implicate administrative members of the state-owned oil company Petrobras, politicians from Brazil's largest parties (including presidents of the Republic), presidents of the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate, state governors, and businessmen from large Brazilian companies. The Federal Police consider it the largest corruption investigation in the country's history.

| Operation Car Wash (Portuguese: Operação Lava Jato) | |

|---|---|

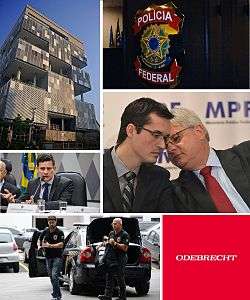

(L–R, top to bottom:) Headquarters of Petrobras in Rio de Janeiro; Emblem of the Federal Police of Brazil; Judge Sérgio Moro; Deltan Dallagnol with Rodrigo Janot; Federal Police in an operation; Odebrecht logo | |

| Country: | Brazil |

| Since: | 17 March 2014 |

| Judge: | Curitiba:

|

| Judge: | Rio de Janeiro:

|

| Judge: | Brasília:

|

| Judge: | Porto Alegre: |

| Judge: | High Court of Justice

|

| Judge: | Federal Supreme Court

|

| Judge: | Federal District

|

| Number of indicted people: | 429[8] |

| Number of convicted people: | 159[8] |

| Number of companies involved: | 18[8] |

| Number of countries involved: | at least 11[9] |

| Number of investigated people: | 429[8] |

| Misappropriated Petrobras funds: | R$6.2 billion[10] (US$2.5 billion[11]:16) |

| Reimbursement requested by Petrobras: | R$46.3 billion[12]:147 (c. US$12 billion) |

| Recovered funds: | R$3.28 billion[8][10]:17[12]:321 (US$912 million[11]:17) |

| Penalties paid by Petrobras: | |

| Last updated: November 2019. | |

|

V • T • E | |

| Political corruption | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | ||||||||||||

| Corruption by country | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Originally a money laundering investigation, it expanded to cover allegations of corruption at Petrobras, where executives allegedly accepted bribes in return for awarding contracts to construction firms at inflated prices. This criminal scheme was initially known as Petrolão (Portuguese for "big oil") because of the Petrobras scandal.[14] The investigation is called "Operation Car Wash" because it was first uncovered at a car wash in Brasília.

The aim of the investigation is to ascertain the extent of a money laundering scheme, estimated by the Regional Superintendent of the Federal Police of Paraná State in 2015 at R$6.4–42.8 billion (US$2–13 billion), largely through the embezzlement of Petrobras funds.[15][16]:60[10]:16 It has included more than a thousand warrants for search and seizure, temporary and preventive detention, and plea bargaining, against business figures and politicians in numerous parties.

At least eleven other countries were involved, mostly in Latin America, and the Brazilian company Odebrecht was deeply implicated.[17]

Investigators indicted and jailed some well-known politicians, including former presidents Fernando Collor de Mello, Michel Temer and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The scandal seemed to challenge the impunity of politicians and business leaders and the structural corruption in the political and economic system that had prevailed until then. This was initially thought possible because of the independence of the judiciary.[18]

However documents leaked in June 2019 to Glenn Greenwald at The Intercept suggest that Judge Sergio Moro may have been partial in his decisions,[19] passing on 'advice, investigative leads, and inside information to the prosecutors'[20] to 'prevent Lula’s Workers’ Party from winning' the 2018 elections.[21] Several top jurisprudence authorities and experts in the world have reacted to the leaks by describing former President Lula as a political prisoner and calling for his release.[22][23] Da Silva was ultimately released on November 8, 2019.[24]

Investigation

The initial accusation came from businessman Hermes Magnus in 2008, who reported an attempt to launder money through his company, Dunel Indústria e Comércio, a manufacturer of electronic components. Ensuing investigations culminated in the identification of four large criminal rings, headed by: Carlos Habib Chater, Alberto Youssef, Nelma Kodama, and Raul Henrique Srour.

Investigation at first focused on the four black-market currency dealers and improper payments to Alberto Youssef by companies who had won contracts at Petrobras' Abreu and Lima refinery. After they discovered that "doleiro" (black-market dealer) Alberto Youssef had acquired a Range Rover Evoque for Paulo Roberto Costa, a former director of Petrobras, the investigation expanded nationwide. Costa agreed after he was charged to provide evidence to the investigation.[25] A newly adopted law introduced 'rewarded collaboration' (i.e., plea bargaining) to Brazil, sentence reductions for defendants who cooperate in investigations. Costa's deposition showed which political parties controlled Petrobras.[26]

It also led to a wave of arrests. Fernando Soares, also known as "Fernando Baiano," a businessman and lobbyist, was allegedly the connection between major Brazilian construction firms and the government formed by the Workers’ Party (PT) and Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB).[27][28] After Costa and Soares, many others agreed to collaborate with the prosecution and between 2014 and February 2016, the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office (Portuguese: Ministério Público da União) filed 37 criminal charges against 179 people, mostly politicians and businessmen.[18] In December 2017, nearly three hundred people had been accused of crimes in the scandal.[29] After Marcelo Odebrecht, grandson of the company founder, was sentenced to 19 years in prison, he and other Odebrecht executives were willing to act as witnesses and to give information about the broader corruption scheme, because of the sentence reduction incentives of the 'rewarded collaboration' law. Odebrecht had a secret branch used to make illegal payments in several Latin American countries, from Hugo Chávez in Venezuela to Ricardo Martinelli in Panama.[17] Odebrecht was charged with fines totalling $2.6 billion by authorities of Brazil, Switzerland, and the United States after they admitted bribing officials in twelve countries for some $788 million.[29]

Costa and Youssef entered into a plea bargain with prosecutors and the scope of the investigation widened to nine major Brazilian construction firms: Camargo Correa, Construtora OAS, UTC Engenharia, Odebrecht, Mendes Júnior, Engevix, Queiroz Galvão, IESA Óleo e Gás, and Galvão Engenharia, as well as politicians involved with Petrobras. Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, who chaired the board of Petrobras from 2003 to 2010, denied knowledge of any wrongdoing.[30] The Brazilian Supreme Court authorized the investigation of 48 current and former legislators, including former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in March 2016.[14] Eduardo Cunha, president of the Chamber of Deputies from 2015 to 2016, was convicted of taking approximately $40 million in bribes and hiding funds in secret bank accounts and sentenced to 15 years in prison.[31][32]

On 19 January 2017, a small plane carrying Supreme Court Justice Teori Zavascki crashed into the sea near the tourist city of Paraty in the state of Rio de Janeiro, killing the magistrate and four other people. Zavascki had been handling Operation Car Wash corruption trials.[33]

A Miami Herald report noted in September 2017 that when Operation Car Wash began, fewer than 10,000 electronic monitoring bracelets were in use to enforce home detentions sentences; by September 2017 the number had ballooned to more than 24,000.[34]

Effect on Petrobras

Petrobras delayed reporting its annual financial results for 2014, and in April 2015 released "audited financial statements" showing $2.1 billion in bribes and a total of almost $17 billion in write-downs due to graft and overvalued assets,[35] which the company characterized as a "conservative" estimate. Had the report been delayed by another week, Petrobras bondholders would have had the right to demand early repayment. Petrobras also suspended dividend payments for 2015. Due in part to the impact of the scandal, as well as to its high debt burden and the low price of oil, Petrobras was also forced to cut capital expenditures and announced it would sell $13.7 billion in assets over the following two years.[35]

Domestic politics

- The treasurer of the Workers' Party (PT), João Vaccari Neto, was arrested for receiving "irregular donations".[36]

- The former chief of staff for President Lula, José Dirceu, was arrested for organising a large part of the bribery.[37]

- The President of the Chamber of Deputies, Eduardo Cunha (PMDB-RJ), investigated for receiving more than US$40 million in kickbacks and bribes.[38][39]

- Former president and current Senator Fernando Collor de Mello, of the Christian-conservative Christian Labour Party (PTC), was charged with corruption.[40]

On 8 March 2016, Marcelo Odebrecht, CEO of Odebrecht and grandson of the company's founder, was sentenced to 19 years in prison after being convicted of paying more than $30 million in bribes to Petrobras executives.[41][42]

In April 2018, former president Luíz Inácio Lula da Silva – after having been sentenced for passive corruption and money laundering in relation to a luxury apartment in Guarujá received from Grupo OAS – entered prison in Curitiba to serve his 12 year sentence. However, illegal communications between Car Wash prosecutors and its lead judge came to light in mid-2019, in which the parties suggested that their prosecutorial motive was to prevent Lula's re-election. There were calls to release the former president (see Leaked conversations below). As a result, he was released on 8 November 2019 after a supreme court ruling.[43]

On 3 July 2018, failed Brazilian billionaire Eike Batista was convicted of bribing former Rio de Janeiro governor Sergio Cabral for state government contracts, having paid Cabral US$16.6 million, and was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment.[44]

Political parties

Lula and the Worker's Party

Emílio Odebrecht said in a written report to the Attorney General of Brazil's Office (PGR) that he discussed donations to Worker's Party's (PT) campaigns with former PT president Lula. Financial support, according to the contractor, came even before Lula became president.[45][46] Marcelo Odebrecht said that the "Amigo" account for former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, was created in 2010 with a balance of R$40 million. In his statement, he said he gave the money to Antonio Palocci, former Finance Minister and Rousseff's chief of staff, who had been the PT contact with Odebrecht since the prior administration, when Emílio Alves Odebrecht and Pedro Novis had handled payments. He said that in the middle of 2010, at the end of the Lula administration, he knew that Dilma Rousseff was going to take over and that the balance of the account would be "managed by her at her request". Thus, he set apart a sum that would be destined exclusively for the former president. He said that Lula never asked directly for donations and that everything was done through Palocci, but it became clear that the donations were ultimately for the former president.[47][48]

| Wikinews has related news: |

On 4 March 2016, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was detained and questioned for three hours as part of the fraud inquiry into the dealings of Petrobras, and his house raided by federal police agents. Lula, who left office in 2011, denied allegations of corruption. Police said they had evidence that Lula, 70, had received kickbacks. Lula's institute called actions against him "arbitrary, illegal and unjustifiable", since he had been cooperating with the investigations.[49] Lula, convicted of accepting bribes worth 3.7 million reals[lower-alpha 2] (1.2 million dollars), was sentenced on 12 July to nine and a half years in prison.[50] He appealed the sentence to the Federal Regional Court-4, which increased his sentence to twelve years and a month.[51] On 5 April 2018, Moro ordered his imprisonment, and he surrendered two days later.[52]

Temer and Brazilian Democratic Movement

The plea bargain testimony by Odebrecht Engenharia Industrial's former president Márcio Faria da Silva said that on 15 July 2010, President Michel Temer led a meeting about an agreement to pay approximately US$40 million in bribes to the Brazilian Democratic Movement in exchange for contracts with the international Board of Directors of Petrobras. According to Faria, Temer, who at the time was a candidate for vice-president on Dilma Rousseff's ticket, delegated to Eduardo Cunha and Henrique Eduardo Alves, then deputies and present at the meeting, the task of making the payments which represented 5% of the contract's value. The meeting took place in Temer's political office in São Paulo. He did not discuss any details about the financial agreement, limiting himself to trivial conversations about politics.[53][54]

Aécio and Brazilian Social Democracy Party

Marcelo Odebrecht said in his plea bargain testimony that the Social Democratid (PSDB) party, led by Senator Aécio Neves (PSDB-MG), received at least 50 million reals in exchange for favoring the business contractor in energy deals. He said that improper payments were made due to business deals with two state companies: Furnas and Cemig. The first federal investigation was under the leadership of Dimas Toledo, an ally of Neves, in the early years of the Lula administration (2003–2005). The second state-run investigation was influenced by Aécio during the period when the PSDB was in power in Minas Gerais (2003–2014).[55][56]

Political families

Odebrecht also discussed family involvement. In eleven cases under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Federal Court (STF), investigations implicate father and son, husband and wife, or siblings. The president of the Chamber, Rodrigo Maia (DEM-RJ), has the most family members implicated. Maia was charged in the same investigation as his father, councilor and former mayor Cesar Maia. According to the Odebrecht testimony, Rodrigo obtained cash resources both for his father's campaign and also for himself. The Brazilian Democratic Movement leader of the Senate, Renan Calheiros (AL), was charged along with his son, the governor of Alagoas Renan Filho (PMDB), in two inquiries. They allegedly participated in an agreement to divert resources from work on the Canal do Sertão and also received resources in the form of a slush fund they refer to as a caixa 2. In the case of the father, two other inquiries are ongoing.

The governor of Rio Grande do Norte, Robinson Faria (PSD), was charged along with his son, federal deputy Fábio Faria (PSD-RN). The two allegedly received donations through a slush fund in return for defend Odebrecht Ambiental's interests in the area of basic sanitation in the state. The president of the PMDB, Senator Romero Jucá (RR), has his son, Rodrigo Jucá, as company in one of the inquiries. The father helped Odebrecht negotiate a Provisional Measure and obtained an electoral donation of 150,000 reals for his son. Romero Jucá was also charged in four other inquiries. A father asking for a contribution for a son was also why former minister José Dirceu was investigated along with Zeca Dirceu, federal deputy. The father was able to raise the money for Zeca in exchange for the acting for of Odebrecht interests in the government.

In the Chamber of Deputies, the sons Antônio Britto (PSD-BA) and Daniel Vilela (PMDB-GO) were also investigated along with their parents, Edvaldo Brito (PTB-BA) and Maguito Vilela (PMDB-GO). Senator Kátia Abreu (PMDB-TO) was accompanied by her husband Moisés Pinto Gomes, who brokered cash payments for her in 2014. Senator Vanessa Grazziotin (PCdoB-AM) is accompanied by her husband, Eron Bezerra, said to have asked for slush fund cash donations for her. Federal Deputy Décio Nery de Lima (PT-SC) also requested slush funds for the Blumenau municipal campaign in 2012 of his wife, state deputy Ana Paula Lima (PT-SC). The Viana brothers of Acre, Governor Tião Viana (PT) and Senator Jorge Viana (PT), were also charged together. Jorge asked for and Odebrecht paid R$1.5 million in cash two for Tião's campaign in 2010.[57][48]

Payments to Brazilian senators

The names of the senators cited in the report were:

- Romero Jucá (PMDB-RR)

- Aécio Neves da Cunha (PSDB-MG)

- Renan Calheiros (PMDB-AL)

- Fernando Bezerra Coelho (PSB-PE)

- Paulo Rocha (PT-PA)

- Humberto Costa (PT-PE)

- Edison Lobão (PMDB-PA)

- Cássio Cunha Lima (PSDB-PB)

- Jorge Viana (PT-AC)

- Lídice da Mata (Brazilian Socialist Party) (PSB-BA)

- José Agripino Maia (DEM-RN)

- Marta Suplicy (PMDB-SP)

- Ciro Nogueira (PP-PI)

- Dalírio Beber Social Democrat (PSDB-SC)

- Ivo Cassol Progressistas (PP-RO)

- Lindbergh Farias (PT-RJ)

- Vanessa Grazziotin Communist Party (PCdoB-AM)

- Kátia Abreu (PDT-TO)

- Fernando Collor de Mello (PROS-AL)

- Christian Labour (PTC-AL)

- José Serra (PSDB-SP)

- Eduardo Braga (PMDB-AM)

- Omar Aziz (PSD-AM)

- Valdir Raupp (PMDB-RO)

- Eunício Oliveira (PMDB-CE)

- Eduardo Amorim (PSDB-SE)

- Maria do Carmo Alves (DEM-SE)

- Garibaldi Alves Filho (PMDB-RN)

- Ricardo Ferraço (PSDB-ES)

- Antônio Anastasia (PSDB-MG)[58]

Payments to federal deputies

The names of the federal deputies cited in the Odebrecht statement were:

- Rodrigo Maia (DEM-RM)

- Paulinho da Força Solidarity (SD-SP)

- Marco Maia (PT-RS)

- Carlos Zarattini (PT-SP)

- João Carlos Bacelar (PR-BA)

- Milton Monti (PR-SP)

- Daniel Almeida (PCdoB-BA)

- Mário Negromonte Jr (PP-BA)

- Nelson Pellegrino (PT-BA)

- Daniel Vilela (PMDB-GO)

- Jutahy Júnior (PSDB)

- Felipe Maia (DEM-RN)

- Onyx Lorenzoni (DEM-RS)

- Pedro Paulo Teixeira (PMDB-RJ)

- Cacá Leão (PP-BA)

- Jarbas Vasconcelos (PMDB-PE)

- Celso Russomano (PT-SP)

- Dimas Toledo (PP-MG)

- Alfredo Nascimento Party of Republic (PRAM)

- Antonio Brito (PSD-BA)

- Arlindo Chinaglia (PT-SC)

- Heráclito Fortes (PSB-PI)

- Zeca Dirceu (PT-PR)

- Betinho Gomes Social Democrats (PSDB-PE)

- Zeca do PT (PRB-SP)

- Fábio Faria (PT-MS)

- José Carneiro (PSB-MA)

- Júlio Lopes (PP-RJ)

- Paulo Lustosa (PP-CE)

- Rodrigo Garcia (politician) (DEM-SP)

- Lúcio Vieira Lima Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (PMDB-BA)

- Vander Loubet (PT-MS)

- Vicente Cândido (PT-SP)

- Yeda Crusius (PSDB-RS)[58]

Other Brazilian public figures

The names in the Odebrecht statement include other politicians and former public officials:

- Eduardo Paes (PMDB) – Former mayor of Rio de Janeiro

- César Maia (DEM) – Former governor of Rio de Janeiro

- Rosalba Ciarlini Rosado (PP) – former mayor of Mossoró, governor of Rio Grande do Norte.

- Guido Mantega (PT) – Former Finance Minister under Lula and Rousseff

- José Dirceu (PT) – Former Lula minister

- Napoleão Bernardes – Prefect of Blumenau for the PSDB

- Cândido Vaccarezza (PT) – Former deputy

- Paulo Bernardo (PT) – Former Minister of Communication

- Luiz Maguito (PMDB) – Former senator and mayor

- Humberto Kasper – Former director of Trensurb in Rio Grande do Sul

- Marco Arildo Prates da Cunha – Former director of Trensurb

- Ana Paula Lima (PT)– Member

- Rodrigo Jucá (PMDB-AL) – Son of Senator Romero Jucá

- Oswaldo Borges da Costa – Businessman linked to Aécio Neves

- Vital do Rêgo Filho – minister of the Federal Audit Court

- Eron Bezerra, Partido Comunista do Brasil (PC do B) – Former state deputy for Amazonas

- Ulisses César Martins de Sousa – Lawyer and former attorney general of the State of Maranhão

- Valdemar Costa Neto (PR) – Former federal deputy for São Paulo

- Edvaldo Pereira de Brito – Former mayor of Salvador, linked to Deputy Antonio de Brito

- José Ivaldo Gomes

- Vado da Farmárcia – Former Mayor of Cabo de Santo Agostinho PE[59]

- João Carlos Gonçalves Ribeiro – Former secretary of planning for the state of Rondônia, accused of taking a bribe in relationship to the Santo Antônio hydroelectric planton the Madeira River[60]

- José Feliciano de Barros Júnior.[61][62]

Dilma Rousseff's 2014 presidential campaign

Marcelo Odebrecht detailed the payment of 100 million reals for the 2014 presidential campaign of Dilma, requested by then-minister Guido Mantega.[63] The payment was allegedly tied to the approval of Provisional Measure 613, which assisted Braskem, an arm of Odebrecht, and dealt with the Special Chemical Industry Regime (Reiq), and tax incentives to stimulate ethanol production.[64] The former executive said that this was not a direct exchange of favors as was, he says, the negotiation of the 50 million reals passed on to the government for the creation of Crisis Refis to solve the crisis caused by zero Imposto sobre Produtos Industrializados ("Industrialized Products Tax"; IPI)[65], but that the then-minister knew that he was talking to someone who had given money to João Santana. The former executive said he often met Mantega and they both brought their lawsuits to meetings. According to him, the former minister had already asked the executive to "resolve issues" pending with publicist João Santana and the then-treasurer of the PT, João Vaccari. The advertiser always feared political campaigns because of the risk of getting into debt at the end. That's why he made advance payment on the account, to make it quiet.[66]

Former Odebrecht Institutional Relations Director Alexandrino Alencar stated that former minister Edinho Silva, when he became treasurer of Dilma Rousseff's campaign in 2014, asked for two donations from five parties to support the Force of the People, at 7 million reals each.[67] The PCdoB, PDT, PRB, PROS, and PP received the illegal donations, according to the former director of Odebrecht. Together, these parties gave three minutes and twenty seconds of television time to the presidential ticket. In return, said the former director, the contractor hoped to obtain quid pro quos from the elected government. The informant detailed meetings with the politicians in his office and cash deliveries, always made in kind by messengers to hotel rooms or flats. Marcelo Odebrecht said he met with Silva a few times to handle the money for the parties that would join the coalition in 2014. The former Dilma minister allegedly instructed Alencar to directly seek party leaders to pass on the values. He clarified that the interest of the PT was the increase of the time of electoral time in the television, being in a total of eleven minutes and twenty-four seconds, being a third of that time coming from the parties purchased.[68]

Repercussions outside Brazil

During the many years it has been going on, the Car Wash scandal has expanded from its original roots in money laundering, to encompass wider corruption in Brazil, and outside its borders in at least ten other countries, even beyond South America.[9]

Paradise Papers

On 5 November 2017, the Paradise Papers, a set of confidential electronic documents relating to offshore investment, revealed that Odebrecht used at least one offshore company as a vehicle for paying the bribes uncovered through the Operation Car Wash investigation. Marcelo Odebrecht, his father Emílio Odebrecht and his brother Maurício Odebrecht are all mentioned in the Paradise Papers.[69]

Argentina

During the governments of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Néstor Kirchner, Odebrecht was awarded overvalued contracts worth at least US$9.6 billion.[70]

Mexico

In Mexico, the former director of the state-owned oil company Pemex, a close ally of President Peña Nieto, is suspected of receiving US$10 million in bribes from Odebrecht.[71]

Panama

Ramón Fonseca Mora, president of Panama's Panameñista Party, was dismissed in March 2016 due to his involvement in the scandal.[72] The Panama Papers resulted from a hack of his lawfirm's computer systems.

Fonseca and his business partner Jürgen Mossack were arrested and jailed in February 2017.[73] They were released in April 2017 after a judge ruled they had cooperated with the investigation and ordered them each to pay $500,000 in bail.[74][75]

Peru

During the Peruvian presidential election in February 2016, a report by the Brazilian Federal Police implicated President Ollanta Humala in bribery by Odebrecht for public works contracts. President Humala denied the charge and has avoided questions from the media on this matter.[76][77] In July 2017, Humala and his wife were arrested and held in pre-trial detention following investigations into his involvement in the Odebrecht scandal.[78][79] Investigations revealed that Brazilian president Lula da Silva pressured Odebrecht to pay millions of dollars toward Humala's presidential campaign.[80]

In December 2017 Peru's President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski appeared before Congress to defend himself against impeachment over allegations of covering up illegal payments of $782,000 from Odebrecht to Kuczynski's company Westfield Group Capital Ltd. Keiko Fujimori, who had lost the 2016 presidential elections to Kuczynski by a margin of fewer than 50,000 votes, was championing impeachment; her party had already forced out five government ministers. Fujimori herself was later implicated in the Odebrecht scandal over alleged campaign contributions[81] and on 31 October 2018 a judge sent her to 36 months of pretrial detention.[82]

Kuczynski resigned the Presidency on 21 March 2018[83] and was sent to pretrial detention on 10 April 2019.[84] On 17 April 2019, Alan García, a former President of Peru who was also implicated in the scandal, died by suicide from shooting himself in the head while police attempted to arrest him.[85]

Former president Alejandro Toledo (2001–2006) was also implicated in the bribery scandal, and was arrested in Redwood City, California in July 2019 for allegedly taking bribes in connection with a highway construction contract.[86]

Venezuela

In late 2017, Euzenando Prazeres de Azevedo, president of Constructora Odebrecht in Venezuela, told investigators that Odebrecht had made $35 million in campaign contributions to Nicolas Maduro's 2013 presidential campaign in return for Odebrecht projects receiving priority in Venezuela,[87] that Americo Mata, Maduro's campaign manager, initially asked for $50 million for Maduro, settled in the end for $35 million.[87][88] In May 2018, Transparency International showed that only 9 of 33 projects started by Odebrecht in Venezuela between 1999 and 2013 were completed.[89]

Leaked conversations

| Vaza Jato |

|---|

|

| Scandal |

On 9 June 2019, Greenwald and other journalists from investigative journalism magazine The Intercept Brasil started publishing several leaked chat messages exchanged via the Telegram app between members of the Brazilian judiciary system. Some, including then Car Wash judge and former Minister of Justice Sérgio Moro and lead prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol are accused of violating legal procedure during the investigation, trial and arrest of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva allegedly for the sake of preventing him to run for a third term in the 2018 Brazilian general election, among other crimes. Other news agencies, such as Folha de São Paulo and Veja confirmed the authenticity of the messages and worked in partnership with The Intercept Brasil to sort the rest of the material in their possession before releasing it.[90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97]

On 23 July, Brazilian Federal Police made public that they had arrested and were investigating Araraquara hacker Walter Delgatti Neto for breaking into the authorities' Telegram accounts. Neto confessed to the hack and to having given the chat logs to Greenwald. Police said the attack had been perpetrated by abusing Telegram's phone number verification and exploiting vulnerabilities in voicemail technology in use in Brazil using a spoofed phone number. The Intercept neither confirmed nor denied that Neto was their source and cited provisions for freedom of the press in the 1988 Brazilian Constitution.[98]

Greenwald has faced death threats and homophobic harassment from supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro due to his reporting on the Telegram messages.[99] A New York Times profile of Greenwald and his husband David Miranda, a left-wing congressman, said the couple have become targets of homophobia from Bolsonaro supporters as a result of the reporting.[100] The Washington Post reported that Greenwald had been targeted with tax investigations by the Bolsonaro government as retaliation for the reporting,[101] while AP called Greenwald's reporting the first test case for a free press under in the Bolsonaro era.[102]

The Guardian, reporting on retaliation against Greenwald from the Bolsonaro government and its supporters, said the articles published by Greenwald and The Intercept "have had an explosive impact on Brazilian politics and dominated headlines for weeks," adding that the exposés "appeared to show prosecutors in the sweeping Operation Car Wash corruption inquiry colluding with Sérgio Moro, the judge who became a hero in Brazil for jailing powerful businessmen, middlemen and politicians."[103]

After Bolsonaro explicitly threatened to imprison Greenwald for this reporting,[104] Supreme Court justice Gilmar Mendes ruled that any investigation of Greenwald in connection with the reporting would be illegal under Brazilian constitution, calling freedom of the press a "pillar of democracy".[105]

Glenn Greenwald reported that the leaked file is bigger than the one in the Snowden case.[106][107] Fernando Haddad considered the leaks to have potential to become the "greatest institutional scandal in the history of the Brazilian republic".[108][106]

In response to the leaks, several top jurisprudence authorities and experts in Europe and the Americas, such as Susan Rose-Ackerman (praised by Car Wash prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol as the world's top corruption expert), Bruce Ackerman, and Luigi Ferrajoli, voiced their shock at the conduct of the Brazilian authorities and described former President Lula as a political prisoner, calling for his release.[22][23]

Legal aspects in 2019

The decision against Aldemir Bendine was annulled by the Supreme Federal Court[109] due to objections to the trial procedure.

Dramatizations

There are two dramatizations of Operation Car Wash. One is the 2017 film Polícia Federal: A Lei É para Todos (Federal Police: The Law Is for Everyone), directed by Marcelo Antunez (2017), and the other is the Netflix series The Mechanism.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operação Lava Jato. |

- Brazilian Anti-Corruption Act

- Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff

- Impeachment proposals against Michel Temer

- Mani pulite, Italian judicial investigation into political corruption

- Odebrecht–Car Wash leniency agreement

- Offshoots of Operation Car Wash

- in Portuguese:

- Fases da Operação Lava Jato – (Operation Car Wash investigation phases)

- Desdobramentos da Operação Lava Jato fora do Brasil – (Offshoots of Operation Car Wash outside Brazil)

References

Notes

- Investigative judge: like the juge d'instruction in France, but unlike judges in the common law systems in most Anglo-Saxon countries, an investigative judge is both part of the judicial system and carries out pre-trial investigations before prosecution.

- Reals: A real is the Brazilian unit of currency. The plural form in Portuguese is reais, following the standard orthographic rules for pluralization of Portuguese nouns ending in -al. The plural in English is reals.

Citations

- Dantas, Dimitrius (28 February 2017). "'Terabytes' turbinam Lava-Jato". Extra. Globo. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017..

- "Desembargador assina exoneração e juiz Sérgio Moro deixa a Lava a jato". R7. Record. 16 November 2018..

- Carvalho, Cleide (November 22, 2018), "Juíza Gabriela Hardt ficará à frente da Lava a jato em Curitiba até fim de abril (Judge Gabriela Hardt will be in charge of the Car Wash in Curitiba until the end of April)", O Globo , consulted on January 31, 2019.

- Carvalho, Cleide (November 22, 2018), "JLuiz Antonio Bonat é confirmado na antiga vaga de Moro", O Globo , consulted on January 31, 2019

- Conheça Leandro Paulsen, revisor do julgamento de Lula no TRF4 (Meet Leandro Paulsen, reviewer of Lula's trial at TRF4). Veja magazine. Publisher April . January 24, 2018 . Consulted on May 20, 2018

- Dantas, Yuri (November 27, 2015). TRF4 nega HC a José Carlos Bumlai na Lava Jato (TRF4 denies HC to José Carlos Bumlai in Lava Jato). Jota . Consulted on May 20, 2018

- Alegretti, Lais (December 17, 2015). 'Ministro Felix Fischer assume relatoria da Lava Jato no STJ (Minister Felix Fischer takes over Lava Jato's rapporteur at the STJ)" . G1 Globe . Retrieved March 29, 2017

- http://www.mpf.mp.br, Ministério Publico Federal. "A Lava Jato em números no Paraná — Caso Lava Jato" [Car Wash by the Numbers in Paraná State - Car Wash Case]. www.mpf.mp.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Long, Ciara (17 June 2019). "Brazil's Car Wash Investigation Faces New Pressures". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Petrobras - Demonstração Financeira 2018 [Petrobras - Financial Statement 2018] (PDF) (Report) (in Portuguese). Petrobras. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Petrobras - 2018 Financial Report (PDF) (Report). 27 February 2019.

- Petrobras - Formulário de Referência 2019 [Petrobras - Reference Form 2019] (PDF) (Report) (in Portuguese). Petrobras. 2019.

- "Luiz Antonio Bonat é confirmado na antiga vaga de Moro" [Luiz Antonio Bonat is Confirmed in Moro's Old Position] (in Portuguese).

- Connors, Will (6 April 2015). "How Brazil's 'Nine Horsemen' Cracked a Bribery Scandal". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "Lava Jato recupera um terço do rombo máximo estimado na Petrobras" [Car Wash recovers one third of estimated maximum shortfall at Petrobras]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). 30 July 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Audrey Jones de Souza; Raphael Borges Mendes; Jefferson Ribeiro Bastos Braga (2015). Official Car Wash Operation Financial Report Nº 2311/2015-SETEC/SR/DPF/PR (PDF) (Report). Regional Superintendent of the Federal Police of Parana State. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Kurtenbach, S., & Nolte, D. (2017). Latin America's Fight against Corruption: The End of Impunity. GIGA Focus Lateinamerika, (03).

- Fausto, S. (2017). The Lengthy Brazilian Crisis Is Not Yet Over. Issue Brief, 2.

- Vincent Begins (21 August 2019). "The Dirty Problems With Operation Car Wash: News reports have pointed to serious wrongdoing at the heart of the anti-corruption inquiry that has shaken many Latin American countries". The Atlantic.

- "Judge Sergio Moro Directed Car Wash Prosecutors on Lula Case". The Intercept. 17 June 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Judge Sergio Moro Directed Car Wash Prosecutors on Lula Case". The Intercept. 17 June 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Jurista americana admirada por Dallagnol defende libertação de Lula" [American lawyer Admired by Dallagnol Advocates for Lula's Release]. Carta Capital. 12 August 2019.

Jurist Susan Rose-Ackerman, Professor of Jurisprudence at Yale University, expressed support for the release of former President Lula, who has been imprisoned since April 2018 for his role in Operation Car Wash. The American, who is considered one of the world's leading anti-corruption experts, has signed a letter along with 16 other jurists calling for the Supreme Court to release the former president and set aside the verdict.

One oddity: Susan Rose-Ackerman was previously praised by prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, the coordinator of Car Wash investigations. The head of the task force in Curitiba had already recommended that the jurist be interviewed, introducing the professor in social networks as 'the world's biggest expert in political corruption'.

Susan and the other lawyers, all from international universities, say the revelations in the messages exchanged between Dallagnol and Sergio Moro, who was responsible for the charges against Lula, 'were appalling to all legal professionals.' - Bergamo, Mônica (11 August 2019). "Juristas estrangeiros se dizem chocados e defendem libertação de Lula" [Foreign jurists shocked, and call for Lula's release]. Folha de São Paulo.

A group of 17 jurists, lawyers, former ministers of justice and former members of higher courts from eight countries wrote a joint text asking the STF (Supreme Court) to release Lula and set aside the cases he is responding to.

They say the revelations of the scandal involving messages exchanged between prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, coordinator of Operation Car Wash, and Sergio Moro, who convicted Lula, 'appalled all legal professionals.'

'We were shocked to see how the fundamental rules of Brazilian due process were shamelessly violated', they also said in the transcript. 'In a country where justice is the same for everybody, a judge cannot both judge and be a party to a case.'

They went on: 'Because of these illegal and immoral practices, Brazilian Justice is currently experiencing a serious credibility crisis within the international legal community.'

The jurists who signed the manifesto are from countries such as France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, Mexico, the United States, and Colombia. - Shasta Darlington; Taylor Barnes. "Brazil's former President Lula released from prison". CNN. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Kamm, T. (2015). Making sense of Brazil’s Lava Jato scandal. Brunswick Group, April.

- Arruda de Almeida, M., & Zagaris, B. (2015). Political Capture in the Petrobus Corruption Scandal: The Sad Tale of an Oil Giant. Fletcher F. World Aff., 39, 87.

- "Executivo revela atuação de operador do PMDB na Andrade Gutierrez" [Executive reveals PMDB operator performance at Andrade Gutierrez]. Fausto Macedo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Luciano Nacimento (26 April 2016). "In Brazil, lobbyist confirms payment of bribes to lower house speaker". EBC. Agência Brasil. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Felter, C.; Labrador, R. C. (2018). "Brazil's Corruption Fallout". Council on Foreign Relations.

- Costas, Ruth (21 November 2014). "Petrobras scandal: Brazil's energy giant under pressure". BBC. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "Brazil arrests top lawmaker behind impeachment of former president Rousseff: Police". Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- Brad Brooks (30 March 2017). "Former Brazil house speaker Cunha sentenced to 15 years for graft". Reuters. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Raquel Stenzel (20 January 2017). "Brazil Supreme Court judge handling graft probe killed in plane crash". Reuters. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Mimi Whitefield; Andre Penner (5 September 2017). "Brazil engulfed in a corruption scandal with plots as convoluted as a telenovela". Miami Herald. AP. Retrieved 14 February 2018. Caption to the photo within the article by Andre Penner of the AP

- Kiernan, Paul (22 April 2015). "Brazil's Petrobras Reports Nearly $17 Billion in Asset and Corruption Charges". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Jelmayer, Rogerio (15 April 2015). "Brazil Police Arrest Workers' Party Treasurer João Vaccari Neto". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Magalhães, Luciana (3 July 2015). "Brazilian Police Arrest José Dirceu, Ex-Chief of Staff, in Petrobras Probe". WSJ. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Romero, Simon (21 August 2015). "Expanding Web of Scandal in Brazil Threatens Further Upheaval". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Luís Calcagno (27 August 2019). "Relatório da Polícia Federal acusa Rodrigo Maia de caixa três: Segundo a Polícia Federal, presidente da Câmara e o pai, Cesar Maia, receberam R$ 1,6 milhão da Odebrecht de forma velada, entre 2008 e 2014, por meio de outras empresas" (in Portuguese). Correio Braziliense. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Brazil speaker, former president charged in Petrobras corruption". Yahoo. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- Fonseca, Pedro (8 March 2016). "Former Odebrecht CEO sentenced in Brazil kickback case". Reuters. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Brazil Petrobras scandal: Tycoon Marcelo Odebrecht jailed". BBC. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Brazil's former president Lula walks free from prison after supreme court ruling". The Guardian. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Biller, David "Former Brazil Billionaire Batista Hit With 30-Year Sentence," Bloomberg News, 3 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Rodrigo Rangel, Daniel Pereira, Robson Bonin, Laryssa Borges, Marcela Mattos, Felipe Frazão, Hugo Marques and Thiago Bronzatto. "Propina devida ao PT foi discutida com Lula, diz delator" [Kickback Due to Worker's Party Was Discussed with Lula, Says Whistleblower]. Veja. Retrieved 13 April 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ""Seu pessoal está com a goela muito aberta", disse Emílio a Lula" ['Your people have their greedy mitts wide open', Emílio told Lula]. O Povo. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Audio: Marcelo Odebrecht tells Moro that he tells 'Amigo', referring to Lula, started with $ 40 million". 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Rodrigo Rangel and Daniel Pereira (12 April 2017). "Lula asked Odebrecht for $40 million in tips". Veja. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- BBC News Brazil Petrobras scandal: Former president Lula questioned

- "Lula é condenado a 9 anos e 6 meses de prisão por tríplex em Guarujá" [Lula Sentenced to 9 Years 6 Months for Guarujá Apartment]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). 12 July 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "Tribunal aumenta pena e condena Lula a 12 anos e um mês de prisão no caso tríplex" [Court Increases Lula's Sentence to 12 years One month in Apartment Case]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). 24 January 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "Lula é preso" [Lula Convicted]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). 7 April 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Fábio Fabrini, Breno Pires e Carla Araújo, de Brasília (12 April 2017). "Temer comandou reunião de acerto de propina de US$ 40 milhões, afirma delator" [Temer Ordered USD $40 Million Kickback Meeting, Says Whistleblower]. Estadão. Retrieved 13 April 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Temer comandou reunião que acertou propina de US$ 40 milhões da Odebrecht, diz delator" [Temer Called Meeting That Paid USD $40 million Kickback from Odebrecht, Whistleblower Says]. R7. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Odebrecht: Grupo de Aécio would have received R$ 50 million for influence in the electric sector". Época Negócios. Globo.com. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Thiago Herdy. "Odebrecht: Aécio group received R$ 50 million for influence in the electric sector". O Globo. Globo.com. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "Audio: Marcelo Odebrecht tells Moro that he tells 'Amigo', referring to Lula, started with $ 40 million". O Globo online. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "A lista de Fachin: veja quem será investigado pelo STFs" [Fachin's List: See Who Will Be Investigated by Supreme Courts]. El Pais. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- Paulo, iG São (4 November 2017). "Lava Jato: lista de Fachin inclui nove ministros do governo de Temer" [Operation Car Wash: Fachin's list includes nine government ministers from Temer] (in Portuguese). Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Delações da Odebrecht: João Carlos Gonçalves Ribeiro é suspeito de receber R$ 1 milhão de usina" [Odebrecht delegations: João Carlos Gonçalves Ribeiro Suspected of Receiving R$ 1 million Reals From Power Plant] (in Portuguese). Grupo Globo. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "A lista de Fachin: veja quem será investigado pelo STFs" [Fachin's list: see who will be investigated by STFs]. El Pais (in Portuguese). 12 April 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Delação da Odebrecht: ex-prefeito do Cabo Vado da Farmácia e vereador José Feliciano são suspeitos de corrupção" [Odebrecht delegation: former Cape Vado Mayor of Pharmacy and councilman José Feliciano are suspected of corruption]. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Márcio Falcão and Livia Scocuglia (12 April 2017). «Negotiation of MP made Odebrecht donate$100 mi to Dilma» . JOTA . Retrieved on 14 April 2017

- Leela Landress (9 May 2013). "Brazilian ethanol sector ponders effects of stimulus package". ICIS. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Governo zera IPI de carro 1.0, reduz IOF do crédito e dá mais prazo para financiar – Notícias – UOL Economia" [Government Resets IPI 1.0 car, Reduces IOF Credit and Gives Better Financing Terms - News - UOL Economy]. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- «Executivos da Odebrecht dizem que políticos pediam propina em troca de aprovação de MPs» "Odebrecht executives say politicians asked for bribe in exchange for approval of MPs ." Globo online . 13 April 2017 . Retrieved on 13 April 2017

- Júnia Gama. «Delator reports slush fund to five parties support Dilma in 2014» . The Globe . Globo.com . Retrieved on 14 April 2017 Delator relata caixa dois para cinco partidos apoiarem Dilma em 2014

- «Delator reports slush fund to five parties support Dilma in 2014» . Oglobo online . 13 April 2017 . Retrieved on 13 April 2017. Delator relata caixa dois para cinco partidos apoiarem Dilma em 2014

- Delfino, Emilia (8 November 2017). "Paradise Papers: Salen a la luz 17 offshore de Odebrecht y al menos una se usó para sobornos" [Seventeen Offshore Operations of Odebrecht Come to Light, and At Least One Was Used for Bribes]. Perfil. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "A freer press online: Latin America’s new media are growing up", The Economist 14 July 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Latinnews.com (September 2017) "Former Pemex director suspected of bribery", Mexico & NAFTA Regional Report. ISSN 1741-444X.

- dayra2 (11 March 2016). "Ministro consejero Fonseca Mora se va de licencia" [Minister-Counselor Fonseca Mora Dismissed]. Panamá América (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "Founders of Panama Papers Law Firm Arrested on Money Laundering Charges". icij.org. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Panama grants bail to Mossack Fonseca founders in Brazil corruption case". Reuters. 22 April 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Detained partners of law firm at the heart of Panama Papers scandal granted bail". DW.COM. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Leahy, Joe. "Peru president rejects link to Petrobras scandal". FT.com. Financial Times. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Post, Colin. "Peru: Ollanta Humala implicated in Brazil's Carwash scandal". Peru reports. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- McDonnell, Adriana Leon and Patrick J. "Another former Peruvian president is sent to jail, this time as part of growing corruption scandal". latimes.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Peru's ex-presidents Humala and Fujimori, old foes, share prison". Reuters. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- EC, Redacción (14 December 2017). "Las claves de la prisión preventiva contra Ollanta Humala y Nadine Heredia" [The keys to Preventive Detention Against Ollanta Humala and Nadine Heredia]. El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- Sanchez, Mariana (21 December 2017). "Peru's Congress debates impeachment of President Kuczynski". Lima: Al Jazeera. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Peru: Keiko Fujimori ordered to preventive prison for 36 months (Full Story)". andina.pe. 31 October 2018.

- Collyns, Dan (22 March 2018). "Peru president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski resigns amid corruption scandal". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Aprueban 36 meses de prisión preventiva para Pedro Pablo Kuczynski". CNN (in Spanish). 19 April 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Alan García: Peru's former president kills himself ahead of arrest", BBC, April 17, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- Maya Perry (18 July 2019). "Ex-Peru President Accused of Corruption Arrested in California". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

- "Ousted Venezuelan prosecutor leaks Odebrecht bribe video". Washington Post. 12 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Américo Mata habría recibido pagos de Odebrecht para campaña de Maduro | El Cooperante" [Américo Mata Alleged to Have received Payments from Odebrecht for Maduro's campaign | El Cooperante]. El Cooperante (in Spanish). 25 August 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Transparencia Internacional: Odebrecht completó en Venezuela sólo 9 de 33 obras contratadas (Informe)" [Odebrecht Only Finished 9 of 33 of Their Contracts in Venezuela (Report)]. La Patilla. 13 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Brésil: des magistrats auraient conspiré pour empêcher le retour de Lula" [Brazil: Magistrates Alleged to have Conspired to Prevent Lula's Return] (in French). AFP / Libération. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Brésil: Les enquêteurs anticorruption auraient conspiré pour empêcher le retour au pouvoir de Lula" [Brazil: Anti-Corruption Investigators Conspired to Prevent Lula's Return to Power] (in French). 20 Minutes. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Brazil News: Brazil's Lula convicted to keep him from 2018 election: Report". Al Jazeera. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "Secret Brazil Archive — An Investigative Series by The Intercept". The Intercept. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "HIDDEN PLOT Exclusive: Brazil's Top Prosecutors Who Indicted Lula Schemed in Secret Messages to Prevent His Party From Winning 2018 Election". The Intercept. 9 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "'ATÉ AGORA TENHO RECEIO' Exclusivo: Deltan Dallagnol duvidava das provas contra Lula e de propina da Petrobras horas antes da denúncia do triplex" ['Up Till Now, I've Been Afraid' Exclusive: Deltan Dallagnol doubted Petrobas Kickback Evidence Against Lula Horas Hours Before the Apartment Accusation] (in Portuguese). The Intercept. 9 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "BREACH OF ETHICS Exclusive: Leaked Chats Between Brazilian Judge and Prosecutor Who Imprisoned Lula Reveal Prohibited Collaboration and Doubts Over Evidence". The Intercep. 9 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Veja faz parceria com The Intercept e Folha para divulgar conteúdo da Vaza Jato" [Veja partners with The Intercept and Folha to Disseminate Content of Car Wash Leaks]. Revista Fórum. 27 June 2019.

- "Entenda o vazamento de diálogos da Lava-Jato" [Understand the Operation Car Wash Leaked Document Dialogs]. www.nsctotal.com.br (in Portuguese). NSCTotal. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Glenn Greenwald becomes focus of Brazil press freedom debate". The Associated Press (AP). 12 July 2019.

- ""The Antithesis of Bolsonaro": A Gay Couple Roils Brazil's Far Right". The New York Times). 20 July 2019.

- "Glenn Greenwald has faced pushback for his reporting before. But not like this". The Washington Post). 13 July 2019.

- "Glenn Greenwald becomes focus of Brazil press freedom debate". Associated Press (AP)). 12 July 2019.

- "Outcry after reports Brazil plans to investigate Glenn Greenwald". The Guardian. 3 July 2019.

- "Glenn Greenwald becomes focus of Brazil press freedom debate". The Associated Press (AP). 12 July 2019.

- "Brazil Top Court Prevents Investigation Into US Journalist". The New York Times. 9 August 2019.

- "Brazil News: Brazil's Lula convicted to keep him from 2018 election: Report". Al Jazeera. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "Material ainda não revelado reforça interferência de Moro, diz Greenwald" [Undisclosed Material Reinforces Moro Interference, says Greenwald]. noticias.uol.com.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Fernando Haddad [@Haddad_Fernando] (9 June 2019). "Podemos estar diante do maior escândalo institucional da história da República. Muitos seriam presos, processos teriam que ser anulados e uma grande farsa seria revelada ao mundo. Vamos acompanhar com toda cautela, mas não podemos nos deter. Que se apure toda a verdade!" [We could be facing the greatest institutional scandal in the history of the Republic. Many could be arrested, processes could be nullified and a great farce could be revealed to the world. We will follow with caution, but we can not stop. Let the truth come true!] (Tweet) (in Portuguese) – via Twitter.

- "Supremo anula pela primeira vez condenação imposta por Moro na Lava Jato" [Supreme Court for First Time Annuls a Conviction Imposed by Moro in Operation Car Wash] (in Portuguese). Folha de S.Paulo. 27 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

External links

- Legislação brasileira traduzida para o Inglês – official English translations of the Constitution, and dozens of other laws