Knockcroghery

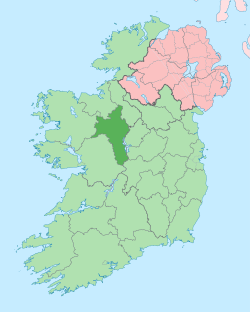

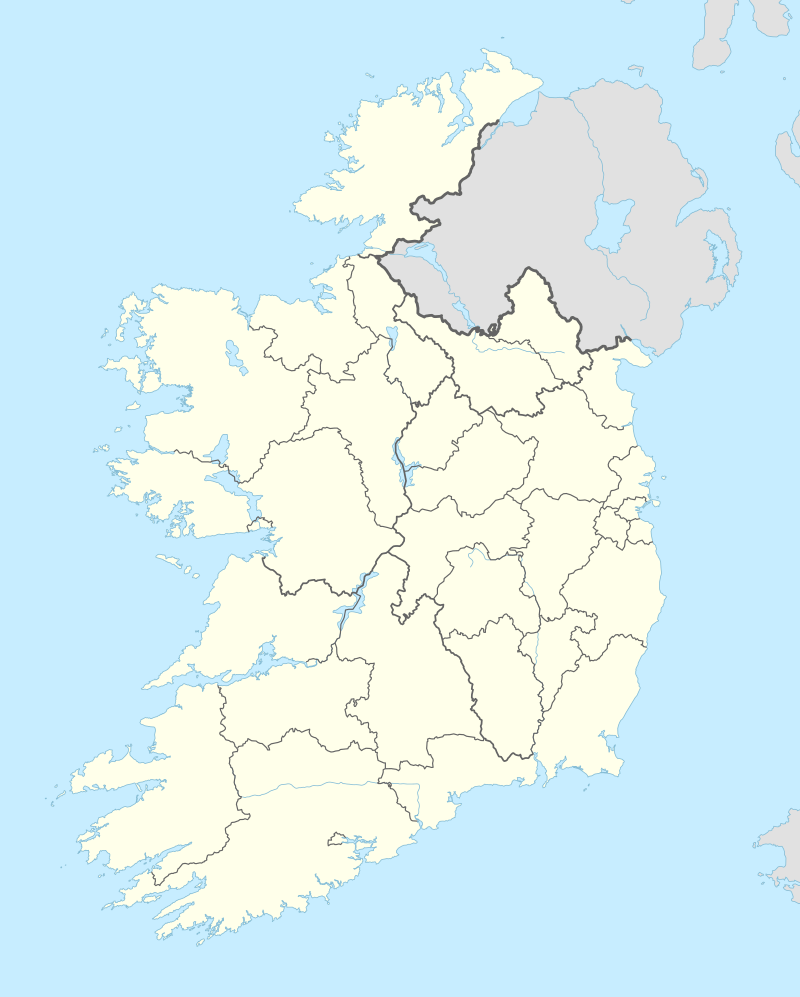

Knockcroghery (Irish: Cnoc an Chrocaire) is a village in County Roscommon, Ireland. It is located between Athlone and Roscommon town, near Lough Ree on the River Shannon. It is one of the closest populations centres to the geographical centre of Ireland.

Knockcroghery Cnoc an Chrocaire | |

|---|---|

Village | |

.jpg) Knockcroghery's national (primary) school | |

Knockcroghery Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 53°34′34″N 8°05′31″W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Connacht |

| County | County Roscommon |

| Elevation | 82 m (269 ft) |

| Population (2016)[1] | 351 |

| Irish Grid Reference | M934574 |

History

Name

The village nestles at the foot of a stony ridge, which protects it from the east wind that sweeps in from Galey Bay. This accounts for the original name of the village, 'An Creagán', meaning 'the stoney hill'.

During Oliver Cromwell's conquest of Connacht in 1650-1652, Sir Charles Coote laid siege to Galey Castle, the seat of the Ó Ceallaigh clan. The Ó Ceallaighs resisted, and for their defiance, they were taken to An Creagán and hanged on the stepped hill just north of the village, now commonly known as Hangman's Hill. The village thereafter came to be known as ‘Cnoc an Chrochaire,’ 'the Hill of the Hanging', now Anglicised as ‘Knockcroghery’.[2][3]

The Burning of Knockcroghery

In the early hours of 19 June 1921, the Black and Tans set Knockcroghery village alight.[4] It was an act of vengeance for the killing of a British general in Glassan two days previously by the Westmeath Volunteers. British intelligence agents mistakenly believed that the killers had come across Lough Ree from the Galey Bay/Knockcroghery area. The Black and Tans arrived in four lorries and parked at St. Patrick's Church. Reportedly drunk and dressed in civilian clothing, they put masks on their faces, fired shots into the air and ordered the people out of their homes. They easily set fire to the thatched roofs of the cottages, using petrol. They were less successful in setting Murray's, Flanagan's and the presbytery alight, due to their slated roofs. Having no time to take their possessions with them, the people rushed from their houses onto the street, still in their nightshirts.[5][6] Canon Bartholomew Kelly refused to leave his house, until the Black and Tans began dousing his furniture with petrol. He jumped out of his bedroom window onto a shed twelve feet below, and hid himself until they had left. His slate roof saved his house from being totally destroyed.[7] Unable to set Murray's roof alight, the Black and Tans set fire to the back door. John Murray reacted quickly to put the fire out, saving the house. The occupants of the thatched houses did not have this opportunity, and their houses burned to the ground very quickly. Michael O' Callaghan described the scene: "the raiding forces drove up and down the village, firing shots at random, cursing loudly, and laughing at the plight of the people of Knockcroghery. The people were terrified, particularly the children, whose cries of fear added to the terrible scene."[8] The flames above Knockcroghery alerted the people for miles around to what had happened, and by daylight, the street was full of people.[9] On the evening of the burning, there had been fifteen houses on the main street of Knockcroghery, most of them single-storey thatched cottages. By the following morning, all but four had been burned to the ground.[10] Jamesie Murray remembered the assistance given to the now homeless people of Knockcroghery: "They came from all over to help. People brought clothes, and a fund was soon set up. The families who were now homeless were accommodated in the vicinity, many staying with relatives who lived nearby. Farm sheds were converted into temporary dwellings. Canon Kelly and others found temporary accommodation with Knockcroghery's Church of Ireland rector, Canon Humphries.[11] Later, three or four new cottages were built on the Shrah road and given to bachelors, who then took people in."[12] The village was rebuilt over the next few years, with help from government grants. The rebuilding provided employment locally, at a time when it was needed.[13][14]

Terror at the fair

In November 1920, an RIC constable named Potter, who was stationed in Kiltoom, was cycling with another constable from Roscommon to Kiltoom. Constable Potter was shot dead on the Athlone side of Knockcroghery railway station. A few days later, while a fair was going on in Knockcroghery, a party of Black and Tans arrived in the village, and in an act of retaliation, rounded up all the men into the handball alley and beat them with bull whips. The Black and Tans seized some tins of paint from a local shop and forced the men to paint over a tricolour that had been painted onto the wall of the handball alley some time previously. They then forced the men to place their hands onto the wet paint and then put their hands into their pockets and wipe them on their clothes.[15]

Catholic parish of Knockcroghery

Prior to the 1870s, what is now the parish of Knockcroghery was two separate parishes: Kilinvoy and Kilmaine. The church in Killinvoy was built around the 1810s, when the Penal Laws were being relaxed. It ceased to be used as a church in 1883 but continues to be used as a community centre to this day, and is known as Culleen Hall. The church in Kilmaine was a very old, small thatched building. After it ceased to be used as a church, it was demolished and is now the site of Ballymurray National School.

In the early 1870s, the parishes of Killinvoy and Kilmaine were merged into the parish of St Patrick, Knockcroghery. In the mid-1870s, a decision was made to build a new, more centrally-located church. Lord Crofton of Mote Park gave a site on the Southern edge of Knockcroghery for a nominal rent of a shilling per year. Construction work commenced in 1879 and St Patrick's Church was consecrated on 18 October 1885.[16][17] The cost of construction was £3,000, of which, £1,313 remained outstanding at the time of consecration. Donations were received following an appeal in the sermon at the consecration, which assisted in paying down the debt of the construction.[18][19] [20] The churches in Culleen and Ballymurray closed down, but many of the parishioners of Ballymurray refused to transfer to Knockcroghery, and continued attending the old Ballymurray church at mass time every Sunday to say the Rosary until it was demolished in 1886.[21]

Economy

For over 250 years the village was famous for the production of the tobacco clay pipe, or "Dúidín". By the late 1800s there were up to 100 people involved in the manufacture and distribution of the village’s clay pipes. Production ceased abruptly on 19 June 1921 when the village was burned down by the Black and Tans during the Irish War of Independence. Today, a visitor centre and workshop are located on the original site of Andrew and P.J. Curley’s pipe factory, where pipes are handcrafted using the original methods of production. The clay-pipe visitors centre is located in the middle of the village and sells clay-pipes and other hand-crafted souvenirs.

Until the late 20th century, the village contained a number of shops, a butcher's, a chemist, a florist, a petrol station, a post office, four public houses, a railway station and a garda station. With the rise of the private motor car and the associated convenient access to larger towns, many of these businesses and services have closed. Today, there remain three public houses, a post office and a hairdresser's.

Places of interest

- Nearby at Galey Bay on the shore of Lough Ree stands Galey Castle, seat of the Ó Ceallaigh clan and built in 1348.[22]

- Galey Bay was the location of a regatta held annually from the 1870s till the late 1920s. The regattas were run by Lord Crofton of Mote Park>[23]

- Out in Lough Ree is the island of Inchcleraun named after a sister of Queen Maeve, Clothra. Queen Maeve is said to have been killed here by an enemy while she was bathing. In recent centuries, the island has been nicknamed Quaker Island and the remains of seven churches can be seen on the island to this day.[24][25][26][27][28]

- Portrun is the local lakeside resort, and is popular with tourists and locals alike in the summer months.[29]

- Also in the area stands Scregg House, seat of the Kelly family from the 18th century onwards. On the grounds of the house are some excellent examples of Sheela na Gigs. The building itself is an example of a 3-storey 5-bay mid-18th-century country house.

- Culleen Hall is located 1 km south of Knockcroghery, and is used as a venue for concerts and local events, as well as a local pre-school.[30]

- Hangman's Hill, the site of the hangings of the Ó Ceallaigh clan in the 16th century, is located at the northern end of the village, opposite the Post Office.

- The Clay Pipe Visitors' Centre is located on the site of the former clay pipe factory. Visitors can witness the manufacturing of clay pipes by traditional methods and learn about the history of the industry.

- Beside the Post Office at the northern end of the village is a picnic area on the bank of a stream.

- Saint Dominic's GAA park is home to the local GAA club and is located on the Athlone side of the village.

Architecture

Much of the architecture of the village centre dates from the 1920s, when the village was rebuilt after the burning by the Black and Tans. Some buildings, such as the church, the community centre, the parochial house, Murray's and the Widow Pat's, predate this however.[31][32]

The village's Anglican church was dismantled in the 1970s, the stone being reused to build a church elsewhere. The site formerly occupied by the Anglican church was subsequently occupied by a petrol station. The former rectory associated with the Anglican church remains standing, opposite the post office.[33]

Saint Patrick's Catholic Church

St. Patrick's Catholic Church is an example of late nineteenth-century ecclesiastical design. It features a two-stage bell tower with pinnacles and a more recently added copper spire. It was built commencing in 1879, with the church being consecrated on 18 October 1885.[34][35][36][37] In the early 1950s, the tower and spire were completed, the bell was installed and the choir gallery was built. At the same time, repair works were carried out, the church was replastered internally and wiring for electric lighting and heating was installed in anticipation of the arrival of rural electrification. In the meantime, lighting was provided by a petrol-powered generator.[38]

The carved limestone baptismal font in St Patrick's Church came from the old church in Ballymurray (now the site of Ballymurray National School). It was initially used as a holy water font inside the front door before being moved to its current location beside the altar to be used as a baptismal font. The smaller carved limestone holy water font, which is built into the wall inside the tower door, is believed to have come from the old church in Culleen (now Cullen Hall).

The stained glass windows on the Eastern side of the church depict the history of the church in Ireland, including the old thatched church in Ballymurray.[39]

People

Knockcroghery is known by many as the home of Roscommon's famous All-Ireland winning captain Jimmy Murray (5 May 1917 – 23 January 2007). He captained Roscommon to their only two All-Ireland Senior Football title wins in 1943 and 1944. He was also captain in their 1946 final and replay against Kerry. As the 1943 final also went to a replay, he is the only man to have captained a team in five All-Ireland senior football finals. His public house is a well-known landmark and revered by lovers of Gaelic football from all parts of Ireland.

Events and culture

Knockcroghery Fair was a festival held annually, generally on the third weekend of September, until 2013.[40]

The Galey Bay Regatta, an annual yachting regatta, was held from 1872 until 1913 by the Lords Crofton, who owned a boathouse on Galey Bay of Lough Ree adjoining Galey castle. Many visiting house boats were anchored in the bay during the regatta. The yachts varied from 25-ton cutters to 18-foot spritsail lake boats. The regattas were the idea of Edward Crofton and his brother Alfred. After most of the lands had been sold to the adjoining farmers, the Croftons left the area and the regattas were no more. The Croftons were supported in organising the regattas by enthusiasts who came both from Lough Ree Yacht Club and Lough Derg. Lord Crofton was always the chairman of the organising committee.[41]

Peadar Kearney, writer of The Soldier's Song (Amhrán na bhFiann), also penned the song "Knockcroghery",[42] when he was challenged to find a word to rhyme with the village's name. His success in rhyming "Molly Doherty" with "Knockcroghery" is open to debate.[43]

The traditional Irish phrase, "fáilte Uí Cheallaigh" (an O'Kelly welcome) dates from December 1351 when Uilliam Buí Ó Ceallaigh (the Taoiseach of Uí Mháine, a kingdom that roughly covered what is now East County Galway and South County Roscommon) invited the poets, writers and artists of Ireland to a great feast at his home, Gailey Castle.[44][45] The feast reportedly lasted for a month.[46] It was during this feast that the famous poet, Gofraidh Fionn Ó Dálaigh, wrote the poem, Filidh Éireann go hAointeach, which remembers the great feast.[47][48][49]

Transport

Knockcroghery railway station opened on 13 February 1860 and finally closed on 17 June 1963.[50] Roscommon railway station is now the nearest station and is located 10 km from Knockcroghery village. It is on the Westport-Dublin line, also serving indirect routes to Ballina, Galway and Ennis.

Knockcroghery is served by Bus Éireann's Route 21 (Westport-Athlone), with indirect routes to Galway, Dublin and other towns. The village is situated on the main N61 road between Athlone and Roscommon towns, and near the M6 Galway-Dublin motorway.

References

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Knockcroghery". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- Knockcroghery Village Design Statement 2008, page 3

- "Gailey Castle".

- Cronin, Denis A; Gilligan, Jim (2001). Karina Holton (ed.). Irish fairs and markets: studies in local history. Four Courts Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-85182-525-7. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Healy, P., God Save All Here (1999) at p.21.

- Roscommon People, 24 June 2016, at p. 39

- Roscommon People, 24 June 2016, at p. 39

- O' Callaghan, M., For Ireland and Freedom.

- Healy, P. God Save All Here (1999) at p.21.

- Roscommon People, 24 June 2016, at p. 39

- O'Callaghan, M. "For Ireland and Freedom: Roscommon's Contribution to the Fight for Irish Independence" (1964)

- Healy, P. God Save All Here (1999) at p.21.

- "Burning of Knockcroghery Recalled in New Book".

- "The Burning of Knockcroghery, June 20th 1921".

- O'Callaghan, M. "For Ireland and Freedom: Roscommon's Contribution to the Fight for Irish Independence" (1964)

- Roscommon Messenger, 3 October 1885

- Roscommon Messenger, 24 October 1885

- Roscommon Messenger, 3 October 1885

- Roscommon Messenger, 24 October 1885

- Roscommon Messenger, 7 November 1885

- Coyne, F. (2000) Roscommon Historical and Archaeological Society Journal: St Patrick's Church, Knockcroghery

- "A History of Ireland in Phrases As Gaeilge".

- "Gailey Castle".

- Heraghty, Michael (15 October 2004). "Inchcleraun Island / Quaker Island - Longford -".

- "Islands".

- "Inchcleraun (quaker island), County Longford".

- "Lough Ree".

- "Inchclearaun Island - Newtowncashel - Co. Longford".

- "Portrun Harbour and Heritage".

- Ballagh Montessori Pre-School Archived 2013-02-17 at Archive.today

- "JS Murray, Knockcroghery".

- "Glebe".

- "Glebe".

- Roscommon Messenger, 3 October 1885

- Roscommon Messenger, 24 October 1885

- Coyne, F. (2000) Roscommon Historical and Archaeological Society Journal: St Patrick's Church, Knockcroghery

- St Patrick's Church Building "At Patrick's Church" Check

|URL=value (help). - Coyne, F. (2000) Roscommon Historical and Archaeological Society Journal: St Patrick's Church, Knockcroghery

- Coyne, F. (2000) Roscommon Historical and Archaeological Society Journal: St Patrick's Church, Knockcroghery

- "Traditional Knockcroghery Fair Events Kick Off This Weekend".

- "Gailey Castle".

- "Knockcroghery". National Library of Ireland. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Knockcroghery".

- Ó Conghaile, M. (2018) "Colourful Irish Phrases"

- "A History of Ireland in Phrases As Gaeilge".

- "Interesting Kellys".

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007554?seq=1

- https://bardic.celt.dias.ie/pdf/POEM932.pdf

- https://bardic.celt.dias.ie

- "Knockcroghery station" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Knockcroghery. |