Josiah Henson

Josiah Henson (June 15, 1789 – May 5, 1883) was an author, abolitionist, and minister. Born into slavery, in Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland, he escaped to Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1830, and founded a settlement and laborer's school for other fugitive slaves at Dawn, near Dresden, in Kent County, Upper Canada, of British Canada. Henson's autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (1849), is believed to have inspired the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852).[1] Following the success of Stowe's novel, Henson issued an expanded version of his memoir in 1858, Truth Stranger Than Fiction. Father Henson's Story of His Own Life (published Boston: John P. Jewett & Company, 1858). Interest in his life continued, and nearly two decades later, his life story was updated and published as Uncle Tom's Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (1876).

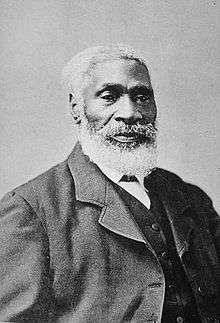

Josiah Henson | |

|---|---|

Josiah Henson in 1877 | |

| Born | June 15, 1789 Charles County, Maryland, United States |

| Died | May 5, 1883 (aged 93) Dresden, Ontario, Canada |

| Nationality | American, Canadian |

| Other names | Uncle Tom |

| Occupation | author, abolitionist, minister, colonizer, soldier, army officer |

| Spouse(s) | Nancy Henson |

| Relatives | Matthew Henson |

| Signature | |

Early life and slavery

Josiah Henson was born on a farm near Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland. When he was a boy, his father was punished for standing up to a slave owner, for which he received one hundred lashes. In addition, his right ear was nailed to the whipping post and then cut off.[2] His father was later sold to someone in Alabama. Following his family's master's death, young Josiah was separated from his mother, brothers, and sisters. His mother pleaded with her new owner, Isaac Riley, and Riley agreed to buy back Henson so she could at least have her youngest child with her, on the condition that he would work in the fields. Riley would not regret his decision, for Henson rose in his owners' esteem, and was eventually entrusted as the supervisor of his master's farm, located in Montgomery County, Maryland (in what is now North Bethesda). In 1825, Mr. Riley fell onto economic hardship and was sued by a brother-in-law. Desperate, he begged Henson, with tears in his eyes, to promise to help him. Duty bound, Henson agreed. Mr. Riley then told him that he needed to take his eighteen slaves to his brother in Kentucky by foot. They arrived in Daviess County, Kentucky, in the middle of April 1825 at the plantation of Mr. Amos Riley. In September 1828, Henson returned to Maryland in an attempt to buy his freedom from Issac Riley.[3] He tried to buy his freedom by giving his master $350, which he had saved up, and a note promising a further $100. Originally, Henson only needed to pay the extra $100 by note. Mr. Riley, however, added an extra zero to the paper and changed the fee to $1000. Cheated of his money, Henson returned to Kentucky and then escaped to Kent County, Upper Canada in 1830, after learning that he might be sold again.

Slavery policy in Canada

Upper Canada had become a refuge for slaves who had escaped from the United States after 1793, when Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe passed "An Act to prevent the further introduction of Slaves, and limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within this Province". The legislation did not immediately end slavery in the colony, but it did prevent the importation of slaves. As a result, any U.S. slave who set foot in what would eventually become Ontario was free. By the time Henson arrived, others had already made Upper Canada their home, including Black Loyalists from the American Revolution and refugees from the War of 1812. In 1833, slavery was outlawed in the British Empire. At this time, Canadians were still a part of colonial British Canada.

Later life

Josiah Henson first worked on farms near Fort Erie, then Waterloo, moving with friends to Colchester in 1834 to set up a Black settlement on rented land. Through contacts and financial assistance there, he was able to purchase 200 acres (0.81 km2) in Dawn Township, in neighbouring Kent County, to realize his vision of a self-sufficient community. The Dawn Settlement eventually reached a population of 500 at its height, exporting black walnut lumber to the United States and Britain. Henson purchased an additional 200 acres (0.81 km2) next to the Settlement, where his family lived. Henson also became an active Methodist preacher and spoke as an abolitionist on routes between Tennessee and Ontario. He also served in the Canadian Army as a military officer, having led a Black militia unit in the Canadian Rebellion of 1837. In 1838, Henson and the militia successfully captured the rebel ship Anne, cutting off their supply lines to southwestern Upper Canada. Though many residents of the Dawn Settlement returned to the United States after slavery was abolished there, Henson and his wife continued to live in Dawn for the rest of their lives.

Works

- The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself. 1849

- Truth Stranger Than Fiction. Father Henson's Story of His Own Life. 1858

- Uncle Tom's Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson. 1876[4]

Miscellaneous

Josiah Henson is the first black man to be featured on a Canadian stamp. He was also recognized by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1999 as a National Historic Person. A federal plaque to him is located in the Henson family cemetery, next to Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site.

A 2018 documentary titled Redeeming Uncle Tom: The Josiah Henson Story covers his life.

Historic sites

The Henson Cabin—Maryland

The actual cabin in which Josiah Henson and other slaves were housed no longer exists.[5] The Riley family house, however, remains and is currently in a residential development in Rockville, Montgomery County, Maryland. After having remained in the hands of private owners for nearly two centuries, on January 6, 2006, the Montgomery Planning Board agreed to purchase the property and the acre of land on which it stands for $1,000,000.[6][7] The house was opened to the public for one weekend in 2006.[8][9] As of March 2009, the site has received an additional $50,000 from the Maryland state Board of Public Works for the planning and design phase of a multiyear restoration project.[10] An additional $100,000 may come from the Federal government that would go towards restoration and planning.[10] The site was planned to be opened permanently to the public in 2012, until then there were guided tours four times a year.[10]

In 2018, Josiah Henson Park, in North Bethesda, Maryland, contains the Riley/Bolton house, where Henson's owner lived. The Montgomery County park site (construction/restoration) is not yet completed. As of 2018, it is open for group tours and on "special occasions". "Ongoing archaeological excavations seek to find where Josiah Henson may have lived on the site."[11]

Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site

Located near Dresden, Ontario, in Canada, Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site includes the cabin that was home to Josiah Henson during much of his time in the area, from 1841 until his death in 1883. The five-acre complex includes Henson's cabin, an interpretive centre about Henson and the Dawn settlement, an exhibit gallery about the Underground Railroad, outbuildings, a 19th-century historic house, a cemetery and a gift shop.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin

See also

References

- See National Underground Railroad to History's "Resistance to Slavery in Maryland," p. 129f.; http://www.nps.gov/subjects/ugrr/discover_history/upload/ResistanceMDRpt.pdf

- "Father Henson's Story of His Own Life". Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself

- cf. Uncle Tom's Cabin, 1852

- Shin, Annys (October 3, 2010). "After buying historic home, Md. officials find it wasn't really Uncle Tom's Cabin". The Washington Post.

- Lenhart, Jennifer (June 15, 2006). "'Uncle Tom's Cabin' Will Open to Visitors". The Washington Post. p. DZ06.

- "Planning Board Approves Purchase of Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site" (PDF) (Press release). Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Montgomery County Planning Board. January 5, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 30, 2008.

- Lenhart, Jennifer (June 8, 2006). "Public to Glimpse 'Uncle Tom's Cabin'". The Washington Post. p. GZ03.

- Lenhart, Jennifer (June 25, 2006). "'Where We Were and Where We Have to Go'". The Washington Post. p. C06.

- Bradford Pearson, "Uncle Tom's Cabin could get government funds", The Olney Gazette, March 4, 2009

- Montgomery Parks, Montgomery County, Maryland (2018). "Josiah Henson Park". Retrieved October 7, 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Josiah Henson. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1900 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about Josiah Henson. |

- Works by Josiah Henson at Project Gutenberg

- Uncle Tom's Story of His Life. An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom"). From 1789 to 1876. With a Preface by Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, and an Introductory Note by George Sturge London: Christian Age Office, 1876.

- The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself. Boston: A. D. Phelps, 1849.

- Truth Stranger Than Fiction. Father Henson's Story of His Own Life. Boston: John P. Jewett, 1858.

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Josiah Henson commemorative stamp

- Digital History: Josiah Henson

- Josiah Henson

- Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site, near Dresden, Ontario

- National Historic Person plaque, and cemetery photo near Dresden, Ontario

- Henson, Josiah (1789-1883).The life of Josiah Henson, formerly a slave. London: Charles Gilpin; Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black; Dublin: James Bernard Gilpin, 1852. This freely downloadable PDF was accessed February 15, 2014.

- The Life of Josiah Henson From the Collections at the Library of Congress