Immigration to Mexico

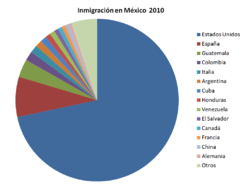

Since the early sixteenth century with the Spanish conquest, Mexico has received immigrants from Europe, Africa (as colonial-era enslaved immigrants), the Americas (e.g., the United States, Canada, Colombia, Guatemala, Argentina, Honduras, Cuba, Brazil and El Salvador), the Middle East and from Asia. Not only today, millions of their descendants still live in Mexico and can be found working in different professions and industries. According to the 2010 National Census, there are 961,121 foreign-born people registered with the government as living in Mexico, the majority of whom are US citizens.[1] This is almost double the 492,617 foreign-born residents counted in the 2000 Census.[1] According to the intercensal estimate conducted in 2015, the foreign-born population was 1,007,063.[2] In 2017, the UN DESA Population Division gave a foreign born population in Mexico of 1,224,169.[3] Unofficial estimates put the total number of foreigners in Mexico closer to four million.[4] More than 45,000 migrants from Central America were deported from Mexico between January and April 2019.[5]

History

Colonial era, 1521-1821

Mesoamerica, that is Central and southern Mexico, already had a large indigenous populations at European contact in the early sixteenth century, which shaped migration patterns to the colony of New Spain. The Spanish crown restricted immigration to its overseas possessions to Catholics with "pure" ancestry, (limpieza de sangre), that is, without taint of Jewish or Muslim ancestors. Prospective immigrants had to obtain a license from the House of Trade in Seville, Spain, attesting to their religious status and ancestry. So-called New Christians, that is Jewish converts to Catholicism, were forbidden from immigrating for fear they had falsely claimed conversion and were in fact crypto-Jews passing as Christians.[6] During the period when Spain and Portugal had the same monarch (1580-1640), many Portuguese merchants immigrated to Mexico. Religious authorities suspected they were crypto-Jews. The Mexican Inquisition was established in 1571 and arrested, tried, and then turned those convicted over to civil authorities for corporal, sometimes capital, punishment in autos de fe.

Early Spanish immigrants to Mexico included men who became crown or ecclesiastical officials, those with connections to the privileged group of conquerors who had access to indigenous labor and tribute via the encomienda, but also Spaniards who saw economic opportunity in Mexico. Not all Spaniards were of noble heritage (hidalgos); many were merchants and miners, as well as artisans of various types. Spanish women immigrated from the conquest era onward, most usually because they joined family members who had already immigrated. Their presence helped consolidate the Spanish colony. Spaniards founded cities, sometimes on the sites of indigenous cities, the most prominent being Mexico City founded on the ruins of Aztec Tenochtitlan. Spaniards preferred living in cities and with so many immigrant artisans present from an early period, Spanish material culture was replicated in Mexico by tailors, leather workers, bakers, makers of weapons, construction workers, book sellers, and medical specialists (barber-surgeons). In 1550, of the 8,000 Spanish immigrants in Mexico City, around ten percent were artisans.[7][8] Some large-scale overseas traders based in Spain also had family members in charge of business in Mexico itself.[9] A few particular towns in Spain sent immigrants to particular towns in Mexico, a notable example being Brihuega, Spain and Puebla, Mexico's second largest town, both of which were textile-producing towns.[10]

African slaves were brought as auxiliaries to Spanish conquerors and settlers from the Spanish conquest onward, but as enslaved persons, they different from European voluntary immigration.[11][12] Because Mexico had such a dense indigenous population, Spaniards imported fewer African slaves than they did the Caribbean, where sugar cultivation necessitated a large labor force and indigenous labors were absent.

Although most European immigrants were from various regions of Spain, there were Europeans with other origins including Italians, Flemish (most prominently Pedro de Gante), Greeks, French, and a few Irish (including William Lamport). Except for the Portuguese, many of these other Europeans assimilated into larger Hispanic society.[13] Seventeenth-century English Dominican friar Thomas Gage spent a few years in central Mexico and Guatemala and wrote a colorful memoir of his time there, but he returned to England and renounced Catholicism.[14] Asians arrived in Mexico via the Manila Galleon and the Pacific coast port of Acapulco. Filipinos, Chinese, and Japanese were part of this first wave, many of them enslaved.[15][16] The most famous of them was Catarina de San Juan, "la china poblana," (Asian woman of Puebla), a slave woman who might have been of Mughal origin.[17]

Post-independence, 1821-1920

Even after Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821, it continued to exclude non-Catholics from immigrating until the liberal Reform. After the fall of the monarchy of Agustín de Iturbide in 1823, the newly established federal republic promulgated a new law regarding immigration, the General Colonization Law. The Spanish crown's controls over foreigners doing business in Mexico were no longer in place, and some British businessmen took an interest in silver mining in northern Mexico.[18] The Mexican government sought to populate areas of the north as a buffer against indigenous attacks. The Mexican government gave a license to Stephen F. Austin to colonize areas in Texas, with the proviso that they be or become Catholics and learn Spanish, largely honored in the breach as more and more settlers arrived. Most settlers were from the slave-holding areas of the southern U.S. and brought their slaves with them to cultivate the rich soil of east Texas. The experiment in colonization in Texas went disastrously wrong for Mexico, with Anglo-Texans and some Mexican Texians rebelling against Mexico's central government and gaining defacto independence in 1836. However, Mexicans of various ideological stripes called for attracting immigrants to Mexico in the nineteenth century.

In the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War (1861-1865), a number of Southerners from the failed Confederate States of America moved to Mexico.[19] Another group migrating to Mexico were Mormons, who sought religious freedom to practice polygamy, and founded colonies in northern Mexico.[20][21] Many Mormons left Mexico at the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution.[22]

During the late nineteenth century when Mexican President Porfirio Díaz (r.1876-1800, 1884-1911) pursued a policy of modernization and development, many from the U.S. settled in Mexico, pursuing roles as financiers, industrialists, investors, and agri-business investors, and farmers. Some did assimilate culturally, learning Spanish and sometimes marrying into elite Mexican families, but many others kept a separate identity and U.S. citizenship.[23] British, French, and German immigrants also became distinct immigrant groups during the Porfiriato.

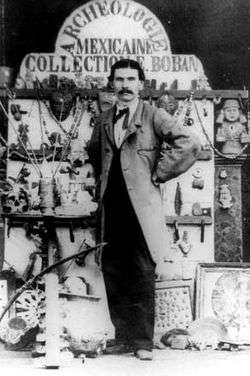

Mass Chinese immigration to Mexico began in the 1876, following mass single-male migrations to Cuba and to Peru where they worked as field laborers coolies. Chinese men immigrated mainly to northern Mexico, and the flow of migration increased following the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act in the U.S. Some then entered the U.S. illegally, but many more stayed in the borderlands area on the Mexican side, where they entered commerce as entrepreneurs of small-scale businesses, creating dry-goods stores and laundries in mining and agricultural towns, as well as small-scale manufacturing and truck farming. They came to monopolize the small-business sector. Chinese merchant houses were established in Pacific coast ports, such as Guaymas, hiring their country-men. There was significant anti-Chinese feeling in northern Mexico, which intensified during the Mexican Revolution.[24] They were expelled from Sonora in the 1930s and their businesses nationalized.[25]

Immigration policy

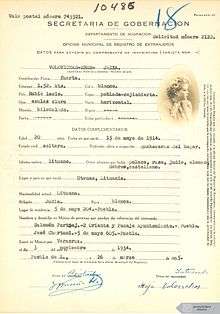

With the Mexican government's intent to control migration flows and attract foreigners who can contribute to economic development, the new migration law simplifies foreigners’ entrance and residency requirements. It replaces the two large immigration categories—immigrant and nonimmigrant—with the categories of “visitor” and “temporary resident”, while keeping the status of “permanent resident”. In the General Law of Population the two categories incorporate over 30 different types of foreigners—i.e. distinguished visitor, religious minister, etc.—each with its own stipulations and requirements to qualify for entry and stay. Under the new law the requirements are simplified, basically differentiating those foreigners who are allowed to work and those who are not. The law also expedites the permanent resident application process for retirees and other foreigners. For granting permanent residency, the law proposes using a point system based on factors such as level of education, employment experience, and scientific and technological knowledge.[26]

According to Article 81 of the Law and Article 70 of the regulations to the law—published on 28 September 2012— immigration officials are the only ones that can conduct immigration procedures although the Federal Police may assist but only under the request and guidance of the Institute of Migration. Verification procedures cannot be conducted in migrant shelters run by civil society organizations or by individuals that engage in providing humanitarian assistance to immigrants.

Undocumented immigration has been a problem for Mexico, especially since the 1970s. Although the number of deportations is declining with 61,034 registered cases in 2011, the Mexican government documented over 200,000 unauthorized border crossings in 2004 and 2005.[27] In 2011, 93% of undocumented immigrants in Mexico came from three countries -Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador- however, there is an increasing number of immigrants from Asia and Africa.[28]

History of immigration policy

Overview of Mexican immigration policy in regards to ethnicity or nationality:

- 1823 - Permanent settlement and naturalization is restricted to Catholics[30] (see also General Colonization Law)

- 1860 - Catholic favoritism ends with the establishment of freedom of religion[30]

- 1909 - First comprehensive immigration law rejects racial discrimination (enacted under the Porfirian regime, but ignored by the governments that followed the Mexican Revolution)[30]

- 1917 - Shorter naturalization times for Latin Americans[30]

- 1921 - Confidential circular, followed by an accord between China and Mexico, restricts Chinese immigration[30]

- 1923 - Confidential circular excludes South Asian Indians[30] (these confidential circulars were kept secretive in order to avoid diplomatic problems, such as with the British Empire or the United States)

- 1924 - Confidential circular excludes blacks[30] (in practice, it excluded working class Afro-Latin Americans, but not elites)

- 1926 - Confidential circular excludes gypsies[30]

- 1926 - Exclusion of those who "constitute a danger of physical degeneration for our race"[30] (see also Blanqueamiento and national policy)

- 1927 - Exclusion of Palestinians, Arabs, Syrians, Lebanese, Armenians and Turks[30]

- 1929 - Confidential circular excludes Poles and Russians[30]

- 1931 - Confidential circular excludes Hungarians[30]

- 1933 - Exclusion or restrictions of blacks, Malays, Indians, the 'yellow race' (East Asians, except Japanese), Soviets, gypsies, Poles, Lithuanians, Czechs, Slovacks, Syrians, Lebanese, Palestinians, Armenians, Arabs and Turks.[30]

- 1934 - Exclusion or restrictions extended to Aboriginals, Latvians, Bulgarians, Romanians, Persians, Yugoslavs, Greeks, Albanians, Afghans, Ethiopians, Algerians, Egyptians, Moroccans and Jews.[30]

- 1937 - Quotas establishes unlimited immigration from the Americas and Spain; 5,000 annual slots for each of thirteen Western European nationalities and the Japanese; and 100 slots for nationals of each other country of the world.[30]

- 1939 - Shorter naturalization times for Spaniards[30]

- 1947 - Law rejects racial discrimination, but promotes a preference for "assimilable" foreigners[30]

- 1974 - Law eliminates assimilability as a gauge for admission[30]

- 1993 - Shorter naturalization times for Portuguese[30] (granted to Latin Americans and Iberians due to historical and cultural connections; requires two years of residence instead of five)

Temporary Migrant Regularization Program

The Programa Temporal de Regularización Migratoria (PTRM) published on 12 January 2015 in the Diario Oficial de la Federación, is directed at those foreigners who have made their permanent residence in Mexico but due to 'diverse circumstances' did not regularize their stay in the country and find themselves turning to 'third parties' to perform various procedures, including finding employment.[31]

The program is aimed at foreign nationals who entered the country before 9 November 2012.[31] Approved foreigners received through the PTRM the status of 'temporary resident', document valid for four years,[31] and are eligible afterwards for permanent residency.[32] The temporary program ran from 13 January to 18 December 2015.[31]

In accordance with the provisions of Articles: 1, 2, 10, 18, 77, 126 and 133 of the Ley de Migración; 1 and 143 of the Reglamento de la Ley de Migración, any foreign national wishing to regularize their immigration status within Mexican territory, under the PTRM will complete the payment of fees for the following:

I. Proof of payment for receiving and examining the application of the procedure... ... MXN 1124.00 (USD 77.14 as of 12 January 2015)

II. For the issuance of the certificate giving them the status of temporary stay for four years ...... MXN 7914.00 (US$514.17)

Through Article 16 of the Ley Federal de Derechos, foreign national are exempt them from payment if it can be proven that they earn a wage at or below minimum wage.[31] During the period that the PTRM is in effect, no fine is applied (as is the practice otherwise).[31]

The PTRM was reenacted on 11 October 2016; eligibility was extended to undocumented migrants that entered the country before 9 January 2015.[32] Migrants are assured that they will not be detained nor deported when inquiring for information or submitting their application at an INM office.[32] Identification and proof of residency/entry date (such as bus or airplane tickets, utility bills, school records or expired visas) should be presented. If these proofs can not be provided, the legal testimony of two Mexicans/resident foreigners may also be accepted. The program runs until 19 December 2017.[32]

Public opinion

The 2019 survey found that 58% of Mexican respondents oppose immigration from Central America.[33]

Immigrant groups in Mexico

Immigrants arrive in Mexico for many reasons, most of the documented immigrants have arrived for economic and/or work-related reasons. Many, such as executives, professionals, scientists, artists, or athletes working for either Mexican or foreign companies, arrive with secure jobs. Retirement is the main motivation for immigrants who tend to be more permanent. Aside from dual national descendants of Mexicans, naturalized Mexicans, or the undocumented, 262,672 foreign residents live on its soil. The majority of its foreign residents are from the U.S. followed by Spain and Guatemala.

North American

American

The largest number of Americans outside the United States live in Mexico. According to Mexico 2010 Census, there are 738,103 Americans living in the Mexican Republic,[1] while the US Embassy in Mexico City has at times given an estimate closer to 1 million (the disparity is due to non-permanent residents, notably the "snowbirds"). Mostly, people who come from the USA are students, retirees, religious workers (missionaries, pastors, etc.), Mexican-Americans, and spouses of Mexican citizens. A few are professors who come employed by Mexican companies to teach English, other English teachers, and corporate employees and executives.

While significant numbers live in Mexico year round, it is probable that a majority of these residents do not stay the whole year. Retirees may live half a year in the U.S. to keep retiree benefits. Those called "snowbirds" come in fall and leave in spring. The American community in Mexico is found throughout the country, but there are significant concentrations of U.S. citizens in all the north of Mexico, especially in Tijuana, Mexicali, Los Cabos, San Carlos, Mazatlán, Saltillo, Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo. Also in the central parts of the country such as San Miguel de Allende, Ajijic, Chapala, Mexico City and Cuernavaca, and along the Pacific coast, most especially in the greater Puerto Vallarta area. In the past few years, a growing American community has developed in Mérida, Yucatán.

Central American

The largest recent immigrant flows to Mexico are from Central America, with a total of 66,868 immigrants from Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama and Nicaragua living in Mexico in 2010.[34]

Recently, Mexico has also become a transit route for Central Americans and others (from the Caribbean, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe)[35] into the United States. 2014 was the first year since records began when more non-Mexicans than Mexicans were apprehended trying to enter the United States illegally through the U.S.-Mexico border.[36] Non-Mexicans (vast majority of whom are Central American) were up from about 68,000 in 2007 to 257,000 in 2014; Mexicans dropped from 809,000 to 229,000 during the same period.[36]

In 2014, Mexico began to more heavily crackdown on these transient migrants.[37] According to Mexican officials, the Plan Frontera Sur (Southern Border Plan) is designed to retake control of the historically porous southern border and protect migrants from transnational crime groups.[37] However, the measures have been widely attributed to pressure from the United States, who does not want a repeat of 2014, when a surge of tens of thousands of women and children clogged up American immigration courts and resulted in a severe lack of space in detention centers at the US-Mexico border.[37] In January 2020, Mexico detained 800 migrants who entered it illegally from Guatemala to reach the United States as part of the strict measures taken by the Mexican authorities to reduce migration to the United States through Mexico.[38]

Cuban

Cuban immigration to Mexico has been on the rise in recent years. A large number of them use Mexico as a route to the U.S., and Mexico has been deporting a large number of Cubans who attempt to. About 63,000 Cubans live in Mexico[39] The number of registered Cuban residents increased 560% between 2010 and 2016, from 4,033 to 22,604 individuals. During the same period, there was a 710% increase in the Cuban presence in Quintana Roo; a fourth of the population (5,569 individuals) live in that state.

South American

Colombian

It is estimated that a total of 73,000 Colombians reside in Mexico.[40] It was not until the 1970s when the presence of Colombians increased under the protection of political asylum as refugees by the Mexican government because of the Colombian guerrilla problems fleeing from their country during the 80s and many of them were protected and kept anonymous to avoid persecution.

Argentines

Argentine immigration to Mexico started in small waves during the 1970s, when they started escaping dictatorship and war in Argentina.

Currently, the Argentine community is one of the largest in Mexico, with about 13,000 documented residents living in Mexico. However, extra-official estimates range the number from 40,000 to 150,000[41][42]

In Quintana Roo, the number of Argentines doubled between 2011 and 2015, and now make a total of 10,000, making up the largest number of foreigners in the state[43]

With two main emigrant waves; during the 1970s Dirty War and after the 2001 economic crisis. The largest Argentine community is in Mexico City (with a sizeable congregation in the Condesa neighborhood) and there are smaller communities in Leon, Guadalajara, Puebla, Cancun, Playa del Carmen, Tulum, Mérida, Monterrey and Tampico. Most Argentines established in Mexico come from the provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Cordoba and Tucuman. The Argentine community has participated in the opening of establishments such as restaurants, bars, boutiques, modeling consultants, foreign exchange interbank markets, among other lines of business.

Venezuela

The most recent influx of immigrants has resulted from the Bolivarian diaspora, a diaspora occurring due to the adverse effects of the Hugo Chávez and his Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela. Compared to the 2000 Census, there has been an increase from the 2,823 Venezuelan Mexicans in 2000 to 10,063 in 2010, a 357% increase of Venezuelan-born individuals living in Mexico.[44]

Mexico granted 975 Venezuelans permanent identification cards in the first 5 months of 2014 alone, a number that doubled that of Venezuelans granted ID cards altogether in 2013 and a number that would have represented 35% of all Venezuelan Mexicans in Mexico in the year 2000.[45][44]

During June 2016, Venezuelans surpassed Americans (historically, first) for number of new work visas granted.[46] The 1,183 visas granted in June were a 20% increase from the 981 granted in May.[46] The main destinations are Mexico City, Nuevo León and Tabasco (due to the state's petroleum industry).[46]

European

Although Mexico never received massive European immigration after its independence, over 1 million Europeans immigrated to Spanish America during the colonial period, which relative to the population of the time, could be said to have been massive European immigration. Although they were in their majority from Spain, other Europeans immigrated illegally. They migrated to Mexico for the most part, and to a lesser extent, Peru. They were called "inmigrantes clandestinos", of which 100,000 were Spanish.

Towards the end of the Porfiriato, there were an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 foreigners in the country.[47] The three largest groups were the Spanish, Americans and Chinese.

From 1911 to 1931, 226,000 immigrants arrived in Mexico,[48] the majority of which were from Europe.

British

There are many Mexicans of English, Welsh and Scottish descent. According to Mexico's Migration Institute in 2009 there were 3,761 British expatriates living in Mexico.[49]

Cornish culture still survives in local architecture and food in the state of Hidalgo. The Scottish and Welsh have also made their mark in Mexico, especially in the states of Hidalgo, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, and Veracruz. British immigrants formed the first football teams in Mexico in the late 19th century. Northern Spaniards of Celtic ancestry like the Asturians, Galicians, and Cantabrians, have also left an imprint in Mexican culture and their languages formed many distinct accents in various regions in Mexico, especially in the central and northern states.

French

Mexico received immigration from France in waves in the 19th and 20th centuries. According to the 2010 census, there were 7,163 French nationals living in Mexico. According to the French consulate general, there are 30,000 French citizens in Mexico as of 2015.[50]

The French language is often taught and studied in secondary public education and in universities throughout the country. French may also be heard occasionally in the state of Veracruz in the cities of Jicaltepec, San Rafael, Mentideros, and Los Altos, where the architecture and food is also very French. These immigrants came from Haute-Saône département in France, especially from Champlitte and Bourgogne.

Another French group were the "Barcelonettes" from the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence département, who migrated specifically to Mexico to find jobs and work in merchandising and are well known in Mexico City, Puebla, Veracruz and Yucatán.

An important French village in Mexico is Santa Rosalía, Baja California Sur, where the French culture/architecture are still found. Other French cultural traits are in a number of regional cultures such as the states of Jalisco and Sinaloa.

The national folk music mariachi is thought to have been named after the French word for "marriage" when the music developed in wedding parties held by French landowning families. It is the legacy of settlers brought in during the Napoleonic-era French occupation is found in Guadalajara, Jalisco. The Second Mexican Empire, created another trend of refuge for French settlers.

For the Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico from the Habsburg dynasty brought with him French, Austrian, Italian and Belgian troops, and after the fall of the Second Empire, most scattered through the area of the Empire. The descendants of these soldiers can be found in the state of Jalisco in the region called Los Altos de Jalisco and in many towns around this region and in Michoacán in cities like Coalcomán, Aguililla, Zamora, and Cotija.

These refugees intermixed with the Austrians, Galicians, Basques, Cantabrians, Italians, and Mexicans in those areas of Michoacán and Jalisco, as well as neighboring states.

During World War II, tens of thousands of French expatriates from Mexico participated in the Free French Forces and the French Resistance, including Mexican-born Lieutenant Rene Luis Campeon of French parentage, was thought to be the first in command to enter Paris during the Liberation of Paris from the retreating Nazis in August 1944.

Other Francophone peoples include those from Belgium such as the Walloons and Franco-Swiss from Switzerland. The Belgians, started by the veteran Ch. Loomans, tried to establish a Belgian colony in the state of Chihuahua called Nueva Bélgica, and hundreds of Belgian settlers established it, but many moved to the capital of the state and other towns around the area, where the Walloon and French could be heard.

The Occitan language can be heard in the state of Guanajuato, it is also known as Langue d'oc is a language originally spoken in Southern France. Also to note is the city Guanajuato has a sizable French expatriate community.

German

The Plautdietsch language, is spoken by descendants of German and Dutch Mennonite immigrants in the states of Chihuahua and Durango. Other German communities are in Nuevo León, Puebla, Mexico City, Sinaloa and Chiapas, and the Yucatán Peninsula. The largest German school outside of Germany is in Mexico City (Alexander von Humboldt school). These represent the large German populations where they still try to preserve the German culture (evident in its popular regional polka-like music types, conjunto and norteño) and language. Other strong German communities lie in Coahuila and Zacatecas (notably the Mennonites), Chiapas (Tapachula) and other parts of Nuevo León (esp. the Monterrey area has a large German minority), Tamaulipas (the Rio Grande Valley in connections to German American culture and Mexican American or Tejano influences), Puebla (Nuevo Necaxa) where the German culture and language have been preserved to different extents. According to the 2010 census, there were 6,214 Germans living in Mexico.[1] As of 2012, about 20,000 Germans reside in Mexico.[51]

Of special interest is the settlement Villa Carlota: that was the name under which two German farming settlements, in the villages of Santa Elena and Pustunich in Yucatán, were founded during the Second Mexican Empire (1864–1867).[52] Villa Carlota attracted a total of 443 German-speaking immigrants, most of them were farmers and artisans who emigrated with their families: the majority came from Prussia and many among them were Protestants.[53] Although in general these immigrants were well received by the hosting society, and the Imperial government honored to the extent of its capabilities the contract it offered to these farmers, the colonies collapsed in 1867.[54] After the disintegration of Villa Carlota as such, some families migrated to other parts of the peninsular, into the United States and back to Germany. Many stayed in Yucatán, where there are descendants of these pioneers with last names such as Worbis, Dietrich and Sols, among others.[55]

Included in the ethnic German immigration to Mexico are from Austria, Switzerland and the French region of Alsace which was part of France since the end of WWI, as well those from Bavaria and High German regions of Germany. . There are about 2,000,000 Mexicans with some partial German ancestry, without counting the ones with total German ancestry, making Mexico 3rd country with the largest German community in Latin America, behind Brazil and Argentina.[56]

Irish

There is also an Irish-Mexican population in Hidalgo and the northern states. According to INM, in 2009 there were 289 Irish expatriates living in Mexico.[57]

Many Mexican Irish communities existed in Mexican Texas until the revolution. Many Irish then sided with Catholic Mexico against Protestant pro-US elements. The Batallón de San Patricio, a battalion of U.S. troops who deserted and fought alongside the Mexican Army against the United States in the Mexican–American War (1846–48). In some cases, Irish immigrants or Americans left from California (the Irish Confederate army of Fort Yuma, Arizona during the U.S. Civil War (1861–65). Álvaro Obregón (O'Brien) was president of Mexico during 1920-24 and Ciudad Obregón and its airport are named in his honor. Actor Anthony Quinn is another famous Mexican of Irish descent. There are also monuments in Mexico City paying tribute to those Irish who fought for Mexico in the 19th century.

Italian

There has not been a huge influx of Italians to Mexico, as there has been to other countries in America such as Argentina, Brazil, and the United States. However, there was an important number of arrivals from northern Italy and Veneto in the late 19th century who are today well assimilated in Mexican society. The exact number of Italian descendants is not known, but it is estimated that there around 85,000 Italian Mexicans in the eight original communities. As of 2012, 20,000 Italians reside in Mexico[51]

Russian

According to INM in 2009 1,396 Russians are living documented in Mexico.[49] According to the Russian embassy, 25,000 reside in Mexico.[58]

Most left Russia during its communist regime (Soviet Union), taking advantage of the Mexican law allowing migrants from communist countries refuge if they touch Mexican soil, and the ability to become legal residents of Mexico. The Spiritual Christian Pryguny were a small early 20th century immigrant group to Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California.

Spanish

Spaniards make up the largest group of Europeans in Mexico. Most of them arrived during the colonial period but others have since then immigrated, especially during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) and the Francisco Franco regime (1939–75).

The first Spaniards who arrived in Mexico, were soldiers and sailors of Extremadura, Andalusia and La Mancha who discovered the Yucatán Peninsula, the shores of the Gulf of Mexico and then made the conquest of what they call the New Spain. Among the soldiers sent by the Spanish crown to the colonial territory were Muslims converts from Córdoba and Granada. At the end of the 16th century, both common and aristocrat people migrated to Mexico and disseminated by its territory.

Most recent immigrants came during the Spanish Civil War. Some of the migrants returned to Spain after the civil war, but some of them remained in Mexico. According to the 2010 census, there were 18,873 Spaniards living in Mexico.[1]

Due to the 2008 Financial Crisis and the resulting economic decline and high unemployment in Spain, many Spaniards have been emigrating to Mexico to seek new opportunities.[59] For example, during the last quarter of 2012, a number of 7,630 work permits were granted to Spaniards.[60]

The article on Basque Mexicans covers the large segment of Spaniards and some French immigrants of the Basque ethnic group.

Other European

Small waves of immigrants from Poland, Ukraine and other Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania etc.), arrived during the Cold War.

Fewer immigrants came from Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Cyprus, Greece (See Greek Mexican), Albania, Croatia, Serbia, Czech Republic, Montenegro, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Slovakia, Slovenia, North Macedonia, Malta, Portugal and Cape Verde.

Asian

Mexico has seen immigration from different parts of Asia throughout its history. The first known Asians arrived during the Colonial era as slaves, labourers and adventurers from the Philippines, southern China and India. Smaller numbers of immigrants came from Korea, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Indonesia, Cambodia, Japan and the Malay peninsula. This group of immigrants were collectively described as "Chino" meaning Chinese despite coming from many diverse origins.[61][62][63] During the early 20th century, a significant number of Asians, primarily Chinese and Korean, were imported as labourers. These immigrants were known as Henequen and Chinetescos and were heavily concentrated in agricultural plantations in the Pacific states (e.g. Sinaloa) and the Yucatán Peninsula.

Korean

A more recent wave (late 20th and early 21st century) of Korean immigrants have arrived as merchants and skilled labourers.[64] Modern immigrants can be found in large cities (especially Mexico City and Monterrey), while Korean descendants are most numerous in the coastal regions like Baja California, Sonora, Guerrero, Veracruz, Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo. According to INM, in 2009 there were 5,518 South Koreans and 481 North Koreans living in México[57] There are an estimated 40,000 descendants of Korean henequen workers.

Chinese

The story of Chinese immigration to Mexico extends from the late 19th century to the 1930s. By the 1920s, there was a significant population of Chinese nationals, with Mexican wives and Chinese-Mexican children. Most of these were deported in the 1930s to the United States and China with a number being repatriated in the late 1930s and in 1960. Smaller groups returned from the 1930s to the 1980s. The two main Chinese-Mexican communities are in Mexicali and Mexico City but few are of pure Chinese blood.[65]

The city of Mexicali in Baja California has the largest Chinese population in Mexico and the largest Chinatown called La Chinesca. The culture and language from the mainly Cantonese and Mandarin-speaking peoples are evident in the food, architecture, and everyday life in Mexico City. The Chinese entered the nation in the 19th century to build railroads, and many xenophobic acts were taken against them because Mexico preferred European immigrants. According to the 2010 Census there are 6,655 Chinese immigrants living in Mexico.[1]

Japanese

The Japanese community is also important in Mexico, and they reside mainly in Mexico City, Morelia, San Luis Potosí, Puebla, Guadalajara, and Aguascalientes, and the immigrant colony in the state of Chiapas known as Colonia Enomoto. The Japanese language is important in their cultural life in Mexico and many institutions for nikkei exist and those wishing to learn the language and their ways of life can attend these lyceums. According to INM, in 2009 there were 4,485 Japanese immigrants residing in Mexico.[49]

Southeast & South Asian

Other Asian communities in Mexico are Indians and Pakistanis followed by Filipinos from the Philippines when the country was under Spanish colonial (1540s-1898) and U.S. American territorial rule (1899–1946). These ethnic groups arrived in the northern states of Mexico as contract farm laborers in the 20th century. And a small Vietnamese community that has close connections with the Vietnamese American community in the United States. The majority of Asian Mexicans live in urban areas or along the US-Mexican border.

There are approximately 200,000 (0.2%) Mexican people who can partly claim Filipino ancestry stemming from colonial times. The Philippines had a connection to Mexico through Spain, as it was administrated from New Spain for over 300 years. According to INM, in 2009 there were 823 immigrants from the Philippines residing in Mexico.[49]

Middle Eastern

Arab

Ethnologue reports that 400,000 Mexicans speak Arabic.[66]

The Arab Mexican population consists of Lebanese, Syrians and Palestinians, whose families arrived in Mexico after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. The majority of them are Christian but some are Muslims.

Business tycoon and billionaire Carlos Slim Helú is the best-known Mexican of this immigrant group, as he is currently ranked by Forbes as one of the richest people in the world. His parents, Maronite Christians, immigrated to Mexico from Lebanon.

Other Middle Eastern

Other members of the Middle Eastern community in Mexico include Armenians.

Foreign-born population by country of birth

Most foreigners in Mexico counted in the Census come from the United States or other Hispanophone countries, with smaller numbers from Europe, East Asia, and the non-Hispanophone Americas. Their numbers have been rising as the country's economy develops, but still comprise less than 1% of the population.

| Place | Country | 2017 | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 899,311 | 738,103 | 343,591 | 194,619 | |

| 2 | 54,508 | 35,322 | 23,597 | 46,005 | |

| 3 | 27,608 | 18,873 | 21,024 | 24,783 | |

| 4 | 20,658 | 13,922 | 6,465 | 4,635 | |

| 5 | 19,214 | 13,696 | 6,215 | 4,964 | |

| 6 | 18,111 | 12,108 | 5,537 | 5,217 | |

| 7 | 16,373 | 10,063 | 2,823 | 1,533 | |

| 8 | 15,417 | 10,991 | 3,722 | 1,997 | |

| 9 | 14,488 | 7,943 | 5,768 | 3,011 | |

| 10 | 12,212 | 7,163 | 5,723 | 4,195 | |

| 11 | 10,315 | 8,088 | 6,647 | 2,979 | |

| 12 | 10,203 | 6,655 | 2,100 | 1,161 | |

| 13 | 9,975 | 6,214 | 5,595 | 4,499 | |

| 14 | 9,083 | 5,886 | 3,749 | 1,633 | |

| 15 | 8,593 | 3,960 | 2,079 | 1,161 | |

| 16 | 7,389 | 5,267 | 3,848 | 2,501 | |

| 17 | 6,359 | 4,532 | 2,320 | 1,293 | |

| 18 | 5,508 | 3,572 | 2,522 | 1,521 | |

| 19 | 5,064 | 4,964 | 3,904 | 2,397 | |

| Other countries | 46,030 | 43,799 | 37,126 | 32,487 | |

| TOTAL | 1,224,169 | 961,121 | 492,617 | 340,246 | |

| Source: INEGI (2000),[67] CONAPO (1990)[68][69] and INEGI (2010)[70] | |||||

See also

References

- "Conociendonos todos" (PDF). INEGI. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- "Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Estados Unidos Mexicanos" (PDF). INEGI. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Table 1: Total migrant stock at mid-year by origin and by major area, region, country or area of destination, 2017". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Opinión: ¿México es un destino de inmigración global?". ADN Político. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Trump announces tariffs on Mexico over immigration". The Hill. 30 May 2019.

- Fisher, John R. "Casa de Contratación" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, pp. 589–90. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Altman, Ida. "Spanish Society in Mexico City After the Conquest." Hispanic American Historical Review (1991)71(3):413-45.

- Altman, Ida et al. The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, pp. 67-68.

- Hoberman, Louisa Schell. Mexico's Merchant Elite, 1590-1660. Durham: Duke University Press 1991.

- Altman, Ida. Transatlantic Ties in the Spanish Empire: Brihuega, Spain, and Puebla, Mexico, 1560-1620. Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo, La población negra de México, 1519-1810: Estudio etnohistórico. Mexico 1946

- Vinson, Ben III. Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018.

- Altman, The Early History of Greater Mexico, p. 263.

- Thomas Gage's Travels in the New World, J.E.S. Thompson (ed.), University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1958.

- Seijas, Tatiana. Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. New York: Cambridge University Press 2014.

- Schurz, William. The Manila Galleon. New York: E.P. Dutton 1939, 1959

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. "A Mughal Princess in Baroque New Spain: Catarina de San Juan (1606-1688), The China Poblana." Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 71 (1997) 37-73.

- Villalobos Velásquez, Rosario. Inmigrantes Británicos en el Distrito Minero del Real del Monte y Pachuca, 1824-1947. Mexico City: The British Council/Archivo Histórico y Museo Minería 2004.

- Wahlstrom, Todd W. The Southern Exodus to Mexico: Migration Across the Borderlands After the American Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

- Hardy, B. Carmon. "The trek south: How the Mormons went to Mexico." The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 73.1 (1969): 1-16.

- Dormady, Jason H., and Jared M. Tamez, eds. Just South of Zion: The Mormons in Mexico and Its Borderlands. University of New Mexico Press, 2015.

- Hardy, B. Carmon. "Cultural" Encystment" as a Cause of the Mormon Exodus from Mexico in 1912." Pacific Historical Review 34.4 (1965): 439-454.

- Hart, John Mason. Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War. Berkeley: University of California Press 2002.

- Hu-Dehart, Evelyn. "Racism and Anti-Chinese Persecution in Mexico." Amerasia 9:2 (1982).

- Hu-Dehart, Evelyn. "Chinese" in Encyclopedia of Mexico . Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 245-248

- Gonzalez-Murphy, Laura. "Protecting Immigrant Rights in Mexico: Understanding the State-Civil Society Nexus," Routledge, New York, Forthcoming 2013

- "Estadísticas"

- "Indios, chinos, somalíes… así son los migrantes invisibles de México". BBC Mundo. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Immigrants in Mexico, census OCDE 2000 OCDE

- FitzGerald, David Scott; Cook-Martín, David (2014). Culling the Masses. Harvard University Press. p. 220. ISBN 0674729048. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Programa Temporal de Regularización Migratoria". Instituto Nacional de Migración. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- "Apoya el INM a extranjeros a que regularicen su situación migratoria, a través del PTRM". gob.mx (in Spanish).

- "Shocking photo of drowned father and daughter highlights migrants' border peril". The Guardian. June 26, 2019.

- Insituto Nacional de Migración “Estadísticas.” 2012. {http://www.inm.gob.mx/index.php/page/Estadisticas_Migratorias}

- "Haitians, After Perilous Journey, Find Door to U.S. Abruptly Shut". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "U.S. border apprehensions of Mexicans fall to historic lows". Pew Research. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- Lakhani, Nina. "Mexico deports record numbers of women and children in US-driven effort". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Mexican security forces detain 800 Central American migrants". Reuters. 2020-01-24. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- "México para cubanos: ¿destino o tránsito? CubanetCubanet". www.cubanet.org.

- "Data". colombianewyork.com. Archived from the original on 2011-11-01.

- "Argentinos en México vivieron la Final - RÉCORD". 8 April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Wayback Machine". 22 December 2005. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007.

- SIPSE, Grupo (18 January 2015). "Argentinos encabezan población de extranjeros en Playa del Carmen".

- "Estadísticas Históricas de México" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics and Geography. pp. 83, 86. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Symmes Cobb, Julia; Garcia Rawlins, Carlos (15 October 2014). "Economic crisis, political strife drive Venezuela brain-drain". Reuters. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Flores, Zenyazen. "Venezolanos desplazan a EU con más permisos para trabajar en México". El Financiero. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- Meyer, Jean. "Los franceses en Mexico durante el siglo XIX" (PDF). El Colegio de Michoacán. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Samuel L. Baily; Eduardo José Míguez (2003). Mass Migration to Modern Latin America. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8420-2831-8. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Rodríguez Chávez, Ernesto; Cobo, Salvador (2012), Extranjeros residentes en México: Una aproximación cuantitativa con base en los registros administrativos del INM (PDF), México: Institution Nacional de Migración, archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2013, retrieved 2013-09-28

- "Mexique". France Diplomatie : : Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères.

- OECD. "International Migration Database". stats.oecd.org.

- Alma Durán-Merk (2007). Identifying Villa Carlota: German Settlements in Yucatán, México, During the Second Empire. Augsburg: Universität Augsburg.

- Alma Durán-Merk (2008a). Nur deutsche Elite für Yukatan? Neue Ergebnisse zur Migrationsforschung während des Zweiten mexikanischen Kaiserreiches. Only "Selected" German Immigrants in Yucatán? Recent Findings about the Colonization Policy of the Second Mexican Empire. In: OPUS Augsburg, <http://opus.bibliothek.uni-augsburg.de/volltexte/2008/1320/pdf/Duran_Merk_Selected_German_Migration.pdf.

- Alma Durán-Merk (2008b): Los colonos alemanes en Yucatán durante el Segundo Imperio Mexicano. In: OPUS Augsburg, http://opus.bibliothek.uni-augsburg.de/volltexte/2008/1329/pdf/Duran_Merk_Colonos_alemanes_Yucatán.pdf.

- A full list with the more than 120 names of the families who colonized "Villa Carlota" as well as the names of the officers and organizers of these colonization program, can be found in: Alma Durán-Merk (2009). Villa Carlota. Colonias alemanas en Yucatán. Mérida: CEPSA/Instituto de Cultura de Yucatán/ CONACULTA, ISBN 978-607-7824-02-2.

- Canal Once (12 April 2012). "Los que llegaron - Alemanes (11/04/2012)" – via YouTube.

- Chavez, Ernesto y Cobo, Salvador, 2012. "Extranjeros Residentes en México: Una aproximación cuantitativa con base en los registros administrativos del INM" INM, Mexico DF, 2012

- "Russians in Mexico". publimetro.com.mx.

- "As Spain's Economy Worsens, Young Adults Flock to Mexico for Jobs - New America Media". newamericamedia.org. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- Flannery, Nathaniel Parish. "As Spain Falters, Spaniards Look to Latin America".

- Leslie Bethell (1984). Leslie Bethell (ed.). The Cambridge History of Latin America. Volume 2 of The Cambridge History of Latin America: Colonial Latin America. I-II (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0521245168.

- Ignacio López-Calvo (2013). The Affinity of the Eye: Writing Nikkei in Peru. Fernando Iwasaki. University of Arizona Press. p. 134. ISBN 0816599874.

- Dirk Hoerder (2002). Cultures in Contact: World Migrations in the Second Millennium. Andrew Gordon, Alexander Keyssar, Daniel James. Duke University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0822384078.

- "Five Generations On, Mexico's Koreans Long for Home". The Chosun Ilbo. 2007-08-16. Archived from the original on 2011-06-21. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- Schiavone Camacho, Julia Maria (November 2009). "Crossing Boundaries, Claiming a Homeland: The Mexican Chinese Transpacific Journey to Becoming Mexican, 1930s-1960s". Pacific Historical Review. Berkeley. 78 (4): 547–565. doi:10.1525/phr.2009.78.4.545.

- "Mexico".

- Los extranjeros en México Archived November 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine INEGI

- Inmigrantes residentes en México por país de nacimiento Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine CONAPO

- "OECD".

- "Los nacidos en otro país suman 961 121 personas" (PDF) (Press release) (in Spanish). INEGI. May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

Further reading

- Alfaro-Velcamp, Theresa. "Arab “Amirka”: Exploring Arab diasporas in Mexico and the United States." Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 31.2 (2011): 282-295.

- Berninger, Dieter George. La inmigración en México (1821-1857), trans. Roberto Gómez Ciriza. Mexico City: SEP-SETENTAS 1974.

- Breceda Pérez, Jorge Antonio. "Ciudadanos y extranjeros en México, análisis crítico de la inequidad normativa en materia de extranjería en la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos." (2018).

- Buchenau, Jürgen. "Small numbers, great impact: Mexico and its immigrants, 1821-1973." Journal of American Ethnic History (2001): 23-49.

- Buchenau, Jürgen. "The Limits of the Cosmic Race: Immigrant and Nation in Mexico, 1850–1950." Immigration and National Identities in Latin America (2014): 66-90.

- Burden, David K., ed. "Reform Before La Reforma: Liberals, Conservatives and the Debate over Immigration, 1846–1855." Mexican *Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 23.2 (2007): 283-316.

- Burden, David K. "La Idea Salvadora: Immigration and Colonization Politics in Mexico, 1821–1857". Doctoral dissertation. University of California, Santa Barbara, 2005.

- Chang, Jason Oliver. Chino: anti-Chinese racism in Mexico, 1880-1940. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

- Covert, Lisa Pinley. San Miguel de Allende: Mexicans, foreigners, and the making of a world heritage site. U of Nebraska Press, 2017.

- Fitzgerald, David. "Nationality and migration in modern Mexico." Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31.1 (2005): 171-191.

- Garc’a, Jerry. Looking Like the Enemy: Japanese Mexicans, the Mexican State, and US Hegemony, 1897-1945. University of Arizona Press, 2014.

- González-Murphy, Laura Valeria. Protecting immigrant rights in Mexico: Understanding the state-civil society nexus. Routledge, 2013.

- Gonzalez-Murphy, Laura V., and Rey Koslowski. "Understanding Mexico’s changing immigration Laws." Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Mexico Institute, http://www. wilsoncenter. org/sites/default/files/G0NZALEZ 20 (2011): 2526.

- González-Murphy, Laura V., and Rey Koslowski. "Entendiendo el cambio a las leyes de inmigración de México." Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Mexican Institute. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://bit. ly/2rSN2YG (consultado el 4 de febrero de 2018) (2011).

- González Navarro, Moisés. Los extranjeros en México, y los mexicanos en el extranjero, 1820-1970. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1993.

- Gurwitz, Beatrice D. "Italian Immigrants and the Mexican Nation: The Cusi Family in Michoacán (1885–1938)." Immigrants & Minorities 33.2 (2015): 93-116.

- Jingsheng, Dong. "Chinese emigration to Mexico and the Sino-Mexico relations before 1910." Estudios Internacionales (2006): 75-88.

- Kim, Hahkyung. "Korean Immigrants’ Place in the Discourse of Mestizaje: A History of Race-Class Dynamics and Asian Immigration in Yucatán, Mexico." Revista Iberoamericana (2012).

- Pani, Erika. Para pertenecer a la gran familia mexicana:: Procesos de naturalización en el siglo XIX. El Colegio de Mexico AC, 2015.

- Pani, Erika. "Ciudadanos precarios. Naturalización y extranjería en el México decimonónico." Historia Mexicana (2012): 627-674.

- Pla, Dolores, et al. Extranjeros en México: Bibliografía. Mexico City: INAH 1993.

- Weis, Robert. "Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Bread, and Class Negotiation in Postrevolutionary Mexico City." Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 25.1 (2009): 71-100.

- Yankelevich, Pablo. "Mexico for the Mexicans: Immigration, national sovereignty and the promotion of mestizaje." The Americas 68.3 (2012): 405-436.