Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (Bengali: হোসেন শহীদ সোহ্রাওয়ার্দী; Urdu: حسین شہید سہروردی; 8 September 1892 – 5 December 1963) was a Bengali[1] politician and a lawyer who was the fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan, serving from his appointment on 12 September 1956 until his resignation on 17 October 1957.

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy حسین شہید سہروردی হোসেন শহীদ সোহরাওয়ার্দী | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th Prime Minister of Pakistan | |

| In office 12 September 1956 – 17 October 1957 | |

| President | Major-General Iskandar Mirza |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Ali |

| Succeeded by | I. I. Chundrigar |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 13 September 1956 – 17 October 1957 | |

| Deputy | Akhter Husain (Defence Secretary) |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Ali |

| Succeeded by | M. Daultana |

| Minister of Health | |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 11 September 1956 | |

| Prime Minister | Muhammad Ali |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 11 September 1956 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Fatima Jinnah (Appointed in 1965) |

| Minister of Law and Justice | |

| In office 17 April 1953 – 12 August 1955 | |

| Prime Minister | Mohammad Ali Bogra |

| Premier of Bengal | |

| In office 23 April 1946 – 14 August 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Khawaja Nazimuddin |

| Succeeded by | Khawaja Nazimuddin (as Chief Minister in East) P. C. Ghosh (as Chief minister in West) |

| Provincial Minister of Civil Supplies | |

| In office 29 April 1943 – 31 March 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Sir K. Nazimuddin |

| Provincial Minister of Labor and Commerce | |

| In office 1 April 1937 – 29 March 1943 | |

| Prime Minister | A. K. Fazlul Huq |

| Deputy Mayor of Calcutta | |

| In office 16 April 1924 – 1 1925 | |

| Mayor | Chittaranjan Das |

| Member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly | |

| In office 1921–1936 | |

| Parliamentary group | Muslim League (Nationalist Group) |

| Constituency | Calcutta |

| Majority | Muslim League |

| President of Awami League | |

| In office 1956–1957 | |

| Preceded by | Maulana Bhashani |

| Succeeded by | A. R. Tarkabagish |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy 8 September 1892 Midnapore, Bengal, British India (Present day in West Bengal in India) |

| Died | 5 December 1963 (aged 71) Beirut, Lebanon |

| Cause of death | Cardiac arrest |

| Resting place | Mausoleum of three leaders in Dhaka, Bangladesh |

| Citizenship | British India (1892–47) Indian (1947–49) Pakistani (1949–63) |

| Political party | East Pakistan Awami League |

| Other political affiliations | Muslim League (1921–51) |

| Spouse(s) | Begum Niaz Fatima (m. 1920; d. 1922) Vera Alexandrovna Tiscenko (m. 1940; div. 1951) |

| Relatives | Hasan Shaheed Suhrawardy (Elder brother) Shahida Jamil (Granddaughter) |

| Residence | DHA estate in Karachi |

| Alma mater | Calcutta University (BS in Maths, MA in Arabic lang.) St Catherine's College, Oxford (MA in Polysci and BCL) |

| Profession | Lawyer, politician |

Born into an illustrious Bengali Muslim family in Midnapore, Suhrawardy was educated at the University of Calcutta and was trained as a barrister in Oxford where he practised law at the Gray's Inn in Great Britain.[2] Upon returning to India in 1921, his legislative career started with his election to the Bengal Legislative Assembly on Muslim League's platform but joined the Swaraj Party when he was invited to be elected as the Deputy Mayor of Calcutta under Chittaranjan Das.

After Chittaranjan Das's death in 1925, Suhrawardy promoted the Muslim unity on a Muslim League platform, and began advocating for the two-nation theory. After the general elections held in 1934, Suhrawardy pushed for strengthening the Muslim League's political programme and asserted his role as becoming one of the Founding Fathers of Pakistan. After joining the Bengal government in 1937, Suhrawardy assumed the only Muslim League-led government after the general elections held in 1945, and faced criticism from the press for his alleged role in the massive riots that took place in Calcutta in 1946.[3]

As the Partition of India loomed in 1947, Suhrawardy championed an alternative to the Partition of Bengal, the idea of an independent united Bengal not federated with either India or Pakistan. This proposal enjoyed some support from Muhammad Ali Jinnah,[4][5][6] but ultimately was not adopted.[7]

Nonetheless, Suhrawardy worked towards integration of East Bengal into the Federation of Pakistan but partied away with the Muslim League when he joined hands to establish the Awami League in 1949.[8][9] During the legislative elections held in 1954, Suhrawardy provided his crucial political support to the United Front that defeated the Muslim League.[8][10] In 1953, Suhrawardy joined the Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra's Ministry of Talents as a Minister of Law and Justice and served his position until 1955.

After supporting the vote of no-confidence motion at the National Assembly that removed Prime Minister Muhammad Ali, the three-party coalition government of Muslim League, Awami League, and the Republican Party, appointed Suhrawardy to the office of Prime Minister, promising to address the issue of economic disparities between the Western Pakistan and the Eastern Pakistan, resolving the energy conservation crises and reforming the nation's military.[10] His foreign policy resulted in increase dependency towards the US foreign aid to the country and pioneering a strategic partnership with the United States against the Soviet Union, and recognised the China by supporting the One-China policy. On the home front, he faced pressure from the business and stock community over his economic policy to distribute the taxation and federal revenues between East Pakistan and West Pakistan, where the controversial issue of national integration had been brought to fruition by the nationalists.[11] After defections from his coalition, and under pressure from President Iskander Mirza, Suhrawardy resigned rather than be dismissed.[12]

Early years

Family background and education

Huseyn Suhrawardy was born on 8 September 1892 in Midnapore, Bengal in India into an illustrious Bengali Muslim family known for their wealth, education, and gentry background, who claimed to be the direct descendants of the First Caliph.[13]:81[2] His father, Justice Sir Zahid Suhrawardy, was a jurist at the Calcutta High Court; and his mother, Khujastha Akhtar Banu, was the daughter of Maulana Ubaidullah Suhrawardy, who was a prolific Urdu language writer and was the first Indian women to have passed the Senior Cambridge examinations.[14] His elder brother, Hasan, a linguist, found a great successful career as a diplomat with Pakistan's Foreign ministry.[14] Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah was his niece.[15] His uncles, Hassan Suhrawardy served in the British Indian Army as a military physician while Sir Abdullah Suhrwardy was a barrister.[14]

After his matriculation from the Calcutta Madrassa, Suhrawardy attended St. Xavier's College, where he earned a BSc.[16][17] In 1913, Suhrawardy attained his MA in Arabic Language and earned a scholarship to attend the Oxford University for his higher studies. His gentry background allowed him to settle in England comfortably while attending the St. Catherine's College of Oxford University, where he attained an MA in political science and graduated with the BCL degree in 1920.[18][19]

After leaving Oxford, Suhrwardy was called to bar at the Gray's Inn where he was trained as barrister-at-Law in 1922–23.[20]

Political career in India

Deputy mayorship of Calcutta and legislation (1922–1944)

After his training as a Barrister-at-Law in England, Suhrawardy returned to India where he begin his practice at the Calcutta High Court in 1922–23, building his reputation as a competent lawyer.[13]:80 During this time, he joined the Muslim League and secured his elections as a Member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly.[2] His legislative career took prominence during the times of the Khilafat Movement, a conservative Islamic movement in India, and had remained associate with it for several years.[13]:80

In 1924–25, Suhrawardy was appointed as deputy mayor of the Calcutta Corporation when he joined the Swaraj Party led by the Mayor of Kolkata Chittaranjan Das.[13]:80 In 1926, he broke with the Swaraj Party after the Hindu-Muslim riots took place in Calcutta, and represented the accused Muslims at the Calcutta High Court, and begin encouraging the trade strikes to maintain pressure on the Congress Party.[21]

In 1930s, he strengthened the political programme of the Muslim League, supporting the concept of Pakistan, and begin mobilising his support in favour of the Pakistan Movement.[2] In 1936, he became the Secretary-General of the Muslim League's Bengal chapter and successfully defended his constituency in general elections held in 1934–37.[2]

He was appointed to head the Ministry of Commerce and Labour in 1937 under the provincial administration of Premier of Bengal A. K. Fazlul Huq.[22]

He served as Minister of Civil Supplies under Bengal's chief minister, Khawaja Nazimuddin. According to author Thomas Keneally, Suhrawardy blamed black marketers and the central government in New Delhi for the Bengal famine of 1943, and claimed he worked tirelessly on relief. Viceroy Archibald Wavell, however, believed that Suhrawardy was corrupt, that he "siphoned money from every project that was undertaken to ease the famine, and awarded to his associates contracts for warehousing, the sale of grain to governments, and transportation."[23]

On the other hand, Indian author, Madhushree Mukherjee, laid major responsibility of this famine to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill who wanted the ration for war efforts only and had refrained the U.S. aid to Bengal.[24] Suhrwardy was further accused of practising the Scorched-Earth policy to counter the Japanese Army's advances in East and supervised to burn thousand fishing boats to block any potential movement of invading Japanese Army troops.[25]:533–535 These measures aggravated starvation and famine and the relief was only ordered when Lord Wavell became the Viceroy, using the Indian Army to organise relief.[25] However, by that time, the winter crop had arrived and famine conditions had already eased, after millions had earlier perished.[25]:534

The Indian press, notably the Hindu press, had become very critical of his role and the Bengali Hindus held him directly responsible for the famine.[26]

Premiership and United Bengal (1946–47)

During the general elections held in 1945 in India, Suhrawardy campaigned against K. Nazimuddin for the Premiership of Bengal, and secured enough political endorsement from the Muslim League that allowed him to form the provincial government as its Prime Minister– the only Muslim League-led government in India in 1946.[2] The Congress Party had been very critical of his role and the government and limited the number of cabinets departments by dismissing the Hindu members of his cabinet.[26]

By 1946–47, the support for the Pakistan Movement among the Indian Muslims had become very popular and it became inevitable for the creation of the nation-state through the partition of India by 1947.[28] The issue of communalism based on the religious beliefs prevented the inclusion of Hindu-majority districts of Punjab and Bengal in the Federation of Pakistan as the Congress Party and their allies the Hindu Mahasabha sought the division of these provinces on communal lines.[28]

To prevent the violence, riots, and long-term border disputes, Suhrawardy joined hands with the demands of preventing the second partition of Bengal by endorsing the idea of independent United Bengal, along with Sarat Chandra Bose, K. Shanker Roy, Abul Hashim, Satya Ranjan Bakshi and F. Q. Choudhri.[29][30]

Suhrawardy reached a compromise with Bose when he sought to form the coalition government between the Congress Party's Bengal section with the Muslim League's Bengal Division.[28] Proponents of the plan urged the Indian public in Bengal to reject the communal divisions and uphold the vision of an independent but united Bengal.[28] In a press conference held in New Delhi on 27 April 1947 Suhrawardy presented his plan for a united and independent Bengal and Abul Hashim issued a similar statement in Calcutta on 29 April.[29]

The issue of United Bengal was met with favourable views and backing of Muhammad Ali Jinnah who saw it for the benefits for Bengali Muslims.[31]:285 Jinnah viewed this plan in a long term geostrategic point in believing that independent Bengal led by Muslim premier would forged a closer alliance with Pakistan than it would with India.[31]:285[27]

Despite Jinnah's backing, the plan was fiercely opposed by K. Nazimuddin and Mohammad Akram Khan, who wanted integration with Pakistan. It also was opposed by most Bengali Hindus, who feared being a minority in a United Bengal, and therefore supported the partition of Bengal to keep West Bengal in India.[32]

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946)

Suhrawardy and other Muslim League leaders reportedly delivered provocative speeches reminding the Bengali Muslims of the historical Islamic victory and urged them to follow the same way on 16 August. The historian Devendra Panigrahi, in his book India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat,[33] quotes from 13 August 1946 issue of Muslim League mouthpiece The Star of India, "Muslims must remember that ... it was in Ramazan that the permission for jehad was granted by Allah. It was in Ramazan that the Battle of Badr, the first open conflict between Islam and Heathenism, was fought and won by 313 Muslims and again it was in Ramazan that 10,000 Muslims under the Holy Prophet conquered Mecca and established the kingdom of Heaven and the commonwealth of Islam in Arabia. The Muslim League is fortunate that it is starting its action in this holy month". On 16 August 1946, the massive bloody riots erupted in Calcutta, killings scores of Hindus at the hands of rioters.[34] However, there is no other claim or evidence have been found. Suhrawardy attempted to control the situation by unsuccessfully calling for peace and deployment of the Indian Army in Calcutta with no success.[34] The riots ended with thousand deaths and the Indian press blaming Suhrawardy of obstructing the police work, which is well documented by several authors and eyewitnesses.[35][36][37] According to authorities, the riots were instigated by members of the Muslim League and its affiliate Volunteer Corps after listening to the speeches made by Nazimuddin and Suhrawardy,[38][39][40][41][42] in the city in order to enforce the declaration by the Muslim League that Muslims were to 'suspend all business' to support their demand for an independent Pakistan.[38][39][40][43] However, supporters of the Muslim League believed that the Congress Party was behind the violence[44] in an effort to weaken the fragile Muslim League government in Bengal, further generating the controversy about the real culprits.[38] Historian Joya Chatterji allocates much of the responsibility to Suhrawardy, for setting up the confrontation and failing to stop the rioting, but points out that Hindu leaders were also culpable.[45]

A senior intelligence operative wrote to a senior British officer based at Fort William after the 'Great Calcutta Killings' after the Calcutta riots revealing Suhrawardy's villainous nature. He wrote, "There is hardly a person in Calcutta who has a good word for Suhrawardy, respectable Muslims included. For years he has been known as "The king of the goondas" and my own private opinion is that he fully anticipated what was going to happen, and allowed it to work itself up, and probably organised the disturbance with his goonda gangs as this type of individual has to receive compensation every now and again."[46] According to Tathagata Roy, the Governor of Tripura, Suhrawardy had pre-planned the riot long back, evident from the fact that demographic changes were being made in the Calcutta Police constabulary.[47] Even the Bangladeshi historian Harun-or-Rashid, in his book The Foreshadowing of Bangladesh: Bengal Muslim League & Muslim Politics: 1906–1947,[48] also disclosed the diabolic role of Suhrawardy in orchestrating riots against the Hindus in a pre-planned manner and safeguarding the Muslim goons from the police.

Eventually, the United Bengal plan eventually failed which had earlier been facing the opposition of the Muslim League led by K. Nazimuddin, Congress Party, the Hindu Mahasabha[49] and the Communist Party of India.[50] Eventually, the Bengali Hindus voted for the partition that created the West Bengal joining the Union of India, and East Bengal was left with no choice but to join the Federation of Pakistan on 14 August 1947.[32]:26–27[27]

Public service in Pakistan

Law and health ministries in coalition government (1953–55)

On 14 August 1947, Suhrawardy lost the control of the Bengal Division of the Muslim League and lost the election when K. Nazimuddin was elected for the Chief Minister of East Bengal.[10] After the partition of India, Suhrawardy remained in Calcutta and made calls for peace with Mahatma Gandhi; he returned in 5 March 1949 to Pakistan.[51]

After Jinnah's death and K. Nazimuddin becoming the Governor-General in 1948, Suhrawardy was forced out from the Muslim League but the latter co-founded the Awami Muslim League, alongside with the conservative cleric, Maulana Bhasani and others in 1949.[10][52] He shifted from Muslim unity to greatly espousing the Bengali nationalism, becoming critical of the Government of East Pakistan.[53] In 1950, he begin opposing the conservative agenda of Prime Minister K. Nazimuddin, and forged an alliance with the Communist Party and other left-oriented parties, which was known as the United Front.[54]

After the dismissal of Prime Minister K. Nazimuddin in 1953, Suhrawardy joined the Ministry of Talents as a Minister of Law and Justice under Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra, taking responsibility of drafting the Constitution of Pakistan.[31]:145 He also oversaw the implementation of the unification of the West Pakistan as a counterbalance to the East, in a prospect for providing the better governance.[31]:145

During the legislative elections in held in 1954 in East, Suhrawardy led the United Front against the Muslim League led by Nurul Amin, which saw the landslide victory of the United Front.[2] The Awami League forged a three-party alliance with the Muslim League and the Republican Party to form the coalition government in the National Assembly.[2] During this time, he was appointed as Health Minister in the three-party coalition government led by Prime Minister Muhammad Ali.

During this time, he also acted as Leader of the Opposition, alongside with the I.I. Chudrigar of the Pakistan Muslim League.[2] After Prime Minister Muhammad Ali refused to support the motion to investigation the Muslim League's allegations on Republican Party led by its President Feroze Khan in 1956, Suhrawardy went onto support the vote of no confidence movement by Muslim League against its own Prime Minister.[2] After supporting the successful vote of no confidence movement at the National Assembly, the Awami League successfully held negotiations with the Muslim League and the Republican Party to appoint Suhrawardy as the new Prime Minister.[11]

Prime Minister of Pakistan (1956–57)

Suhrawardy administration: Internal affairs and constitutional reforms

On 12 September 1956, Chief Justice M. Munir, administrated the oath of Prime Minister Huseyn Suhrawardy in Governor's House in Karachi, then-Federal capital of the country.[55]

Initially promising to review the policy of One Unit status to the nationalists at the National Assembly, Prime Minister Suhrwardy backed out to overturn this scheme.[56] At the National Assembly, Prime Minister Suhrawardy faced politics over two issues pressed by the nationalists: the One Unit and the Electoral College.[57] The issue of One Unit was revived by the nationalists who called for the restoration of the status of the four provinces, beginning to hold massive rallies all around the West.[11][57] Prime Minister Suhrawardy, however, showed less concern over this issue which came at the interests of the East as he had earlier reached the compromise in favour of being appointed as the Prime Minister.[56] Though, the East had not objected the implementation of the One Unit as they were not above the factional battles motivated by personal interests, the West's multi-ethnic diversity background had effectively raised this issue which had won public support and sympathy.[56]

Nonetheless, there were no concrete steps taken by Suhrwardy government to address this issue and it was not until the Yahya administration when it was repealed in 1970.[57] At the National Assembly, the Awami League initiated the constitutional work on reviving the joint electorate system but faced strong pressure and opposition from the Muslim League to implement this issue.[11] The Muslim League had called for the separate electoral system which had subsequent public support over this issue; the East had favoured the joint electorate system.[11]

In 1956, Prime Minister Suhrwardy approved to request the three-year extension of army commander General Ayub Khan while approving the appointment of V-Adm. HMS Choudhry as the first native naval commander– both men served to command their services until 1959.[58]

To address the issue of energy conservation in West, Suhrawardy established the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) inviting its chair to Dr.Nazir Ahmad, a physicist.[59] The nuclear power programme was intended to be for peaceful usages when he affirmed his obiligations towards the clauses of the Atoms for Peace initiative.[59] When his Science Advisor, Dr. Salimuzzaman Siddiqui, presented the plan to acquire the NRX reactor from Canada, Suhrawardy reportedly vetoed instead releasing funds for the U.S.-based Pool-type reactor from the United States in 1956.[59]

U.S. aid and the economic policy

In 1956, Prime Minister Suhrawardy halted the National Finance Commission (NFC) programme to allocate taxed revenue equally between East and West Pakistan. Suhrawardy relied heavily upon U.S. aid to the country to meet food shortages, and asked the U.S. President to ship wheat flour and rice on a regular basis to Pakistan.[60]:375 In East Pakistan, there were reports of another widespread famine, in which, wheat, potatoes, and rice were being sent from the U.S. and West Pakistan's Fauji Foundation to East Pakistan on a regular basis.[60]:374–375

The central government led by Suhrawardy focused on the implementation of the planned economy.[11] His relations with the stock exchange and the business community deteriorated when he announced distribution of the US$10 million ICA aid between West and East, and establishing the shipping corporation at the expense of West Pakistan's revenues.[31]:149 Massive labour strikes broke out in West Pakistan against his economic policy in major cities of Pakistan. Eventually leaders of the stock exchange met with President Mirza to address their concerns and issues.[11]

Foreign policy

Prime Minister Suhrwardy directed the foreign policy towards aligning with the United States against the Soviet Union, and was seen as a pro-American political figure in the country.[62] Suhrawardy harboured strong anti-Soviet views and advocated for strong pro-Western and pro-American policy at the public circles, putting himself at odds with the policy of his own party, the Awami League.[62]

He is considered to be one the pioneers of Pakistan's foreign policy aimed, directed, and set towards excessively supporting the United States and their cause, a policy that was pursued by the successive administrations.[62] On 10 July 1957, Prime Minister Suhrawardy paid a state visit to the United States where he met with President Dwight Eisenhower and accepted his request to lease out an air force base to the United States Air Force that would be in use for the signals intelligence purposes against the Soviet Union. The 1960 U-2 incident severely compromised the national security of Pakistan when Soviet Union eventually discovered the base through interrogating its pilot. In return, the United States distributed ~US$ 2.142 billion in shape of giving the supersonic F-104 Starfighter and M48 Patton tanks and dispatching the assistance group to the Pakistan's military.[63] Suhrawardy's party, the Awami League, split over his signing of the US-Pakistan military pact, with Maulana Bhasani leaving to form the National Awami Party (NAP).[64]

Prime Minister Suhrawardy was invited by the Soviet Union for an informal visit but he declined.[65]

In 1956, Prime Minister Suhrawardy became the Pakistan's first Prime Minister to paid a state visit to China when he went to meet with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing, taking with him the entire diplomatic mission including the Pakistan Ambassador to China, Dr. Ahmed Ali, who had established the Pakistan embassy in Beijing and formed Pak-China friendship and strengthened the official diplomatic friendship between Pakistan and China. In 1957, he well received the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in Karachi when he reciprocated the visit in Karachi.[66]

In 1956–57, Prime Minister Suhrawardy accused India of supporting insurgency in different parts of the country, and levelled accusations against his counterpart, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of undoing the partition of India.[67]

Decline and resignation

His policy inclination towards the United States brought great ire and opposition from within the Awami League, which had been favouring the cleric Maulana Bhasani, who had been suspicious of American motives. Suhrawardy had strongly advocated for Pakistan's membership in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, which was aimed towards containing communism; he was in direct conflict with Bhasani on this issue.[68]

To the dismay of his party, Suhrawardy became closer to President Iskander Mirza on many issues.[66] There were massive protests carried out in the East against Prime Minister Suhrawardy by the Awami League when the United States dispatched a Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to the Pakistani military.[69] Eventually, Bhashani and Yar Mohammad challenged him for the party's presidency, as both men had managed to consolidate the Awami League, but they failed to carry the party mass with them.[62]

Intending to break President Mirza's control over Parliament, Suhrawardy asked President Mirza to call a session of the National Assembly and seek a Vote of Confidence from the Parliament, where Prime Minister Suhrawardy's allies had the majority.[70]

His alignment with the United States at the expense of the Soviet Union caused Prime Minister Suhrawardy to eventually lose control over the presidency of the party to the junior leadership under Abdur Rashid Tarkabagish.[71][72] Threatened with President Mirza's retaliation after the failed parliamentary resolution and facing to have lost the majority in the National Assembly, Prime Minister Suhrawardy faced the similar circumstances as his predecessor and surprisingly tendered his resignation on 17 October 1957.[72][73]

Public and personal life

In 1920, Suhrawardy was arranged to marry, Begum Niaz Fatima (d. 1922), the daughter of Justice Sir Abdur Rahim who was also a politician. The marriage produced two children, Ahmed Shahab Suhrawardy and Jahan Suhrawardy— Ahmed died of pneumonia while studying in London whilst his daughter, Jahan was arranged to marry Shah Ahmed Sulaiman, son of Justice Sir Shah Sulaiman.

After his passing in 1963, the Suhrawardy family remained active in national politics, and his granddaughter Shahida Jamil subsequently is a politician with the PML(N) and briefly served as the Law Minister in 1999 and 2007.

In 1940, Suhrawardy married Vera Alexandrovna Tiscenko, a Russian theatre actress and dancer whom he knew through his older brother's work in Russia. Vera converted to Islam by taking the name of Begum Noor Jehan, and took Pakistani citizenship in 1947.[74] She was a Russian actress of Polish descent from the Moscow Art Theatre and protege of Olga Knipper.[75][76] Suhrawardy and Vera Tiscenko filed for a divorce in Sindh High Court, which was said to be bitter when the Sindh High Court ordered for distribution of Surawardy's wealth with Vera; the divorce was finalised in 1951.

Following the divorce, Vera moved to the United States with their only son, Rashid Suhrawardy, (known as Robert Ashby), who is a British actor living in London and briefly portrayed Jawaharlal Nehru in film Jinnah in 1998.

Legacy

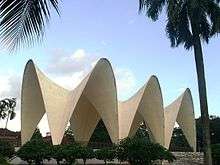

- Suhrawardy Udyan, a historic maidan in Dhaka (formerly the Ramna Race Course).

- Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital, a major government hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Government Shaheed Suhrawardy College, a public college, located in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Government Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy College, a government college in Magura, Bangladesh

- Khayaban-e-Suhrawardy (lit. Garden of Suhrawardy), is one of the main thoroughfares of the Pakistani capital of Islamabad.[78]

- Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy Hall(East Pakistan Agricultural University, now Bangladesh Agricultural University)

- In 2004, Suhrawardy was ranked number 19 in the BBC's poll of the Greatest Bengali of all time.[79]

See also

- Bengali nationalism in Pakistan

- Conservatism in Pakistan

- Bengali culture in Pakistan

- American lobby in Pakistan

- Pakistan–United States relations

References

- Redclift, Victoria (2013). Statelessness and Citizenship: Camps and the Creation of Political Space. Cambridge, UK: Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-136-22032-6.

- "Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy–Former Prime Minister of Pakistan". Story of Pakistan. Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan: Nazaria-i-Pakistan Trust. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Chatterji, Joya (1994). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-521-41128-8.

Hindu culpability was never acknowledged. The Hindu press laid the blame for the violence upon the Suhrawardy Government and the Muslim League.

- Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- Ahmed, Akbar (2005) [First published 1997]. Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-134-75022-1.

At one point, late in the 1940s, he was even prepared to concede an independent Bengal as long as the Muslims of that area had freedom and got Calcutta.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (1998). A History of India. Psychology Press. pp. 290–291. ISBN 978-0-415-15482-6.

- Low, D. A. (1991). Political Inheritance of Pakistan. Springer. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-349-11556-3.

- Harun-or-Rashid (2012). "Suhrawardy, Huseyn Shaheed". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Ahsan, Syed Badrul (5 December 2012). "Suhrawardy's place in history". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "H. S. Suhrawardy Becomes Prime Minister". Story of Pakistan. 1 July 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "The H.S. Suhrawardy government". Story of Pakistan. July 2003. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Talukdar, Mohammad Habibur Rahman, ed. (2009) [First published 1987]. Memoirs of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy with a Brief Account of His Life and Work (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-547722-1.

[Mirza] presented him with a letter from the Republicans, withdrawing their confidence ... and asked Suhrawardy to resign by 10:30 a.m. failing which he would dismiss him. Suhrawardy resigned ... to avoid the ignominy of dismissal.

- Chatterji, Joya (2002). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52328-8. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Ikram, S. M. (1995). Indian Muslims and Partition of India. Lahore, Pun. Pak.: Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 320. ISBN 9788171563746. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Begum Shaista Ikramullah – Former First Female Representative of the first Constituent Assembly of Pakistan". 21 October 2013.

- Talukdar, Mohammad Habibur Rahman, ed. (2009) [First published 1987]. Memoirs of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy with a Brief Account of His Life and Work (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-547722-1.

Later he entered the Calcutta Aliya Madrasah and graduated with honours in science from St Xavier's College.

- Shibly, Atful Hye (2011). Abdul Matin Chaudhury (1895–1948): Trusted Lieutenant of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Juned Ahmed Choudhury. p. 90. ISBN 9789843323231. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Mujibur Rahman, Sheikh (1997). Iqbal, Shahryar (ed.). Sheikh Mujib in Parliament, 1955–58. Agamee Prakashani. p. 407. ISBN 978-984-401-385-8. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Eminent Indians: Who Was Who, 1900–1980, Also Annual Diary of Events. New Delhi: Durga Das Pvt. Ltd. 1985. p. 330. OCLC 14130784. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

Went to Oxford and did M.A., B.Sc (Politics) and B.C.L, with honors in Jurisprudence.

- Chakrabarti, Bidyut (1990). Subhas Chandra Bose and Middle Class Radicalism: A Study in Indian Nationalism, 1928–1940. New Delhi, India: I.B.Tauris. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-85043-149-7. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2015). The Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience (2nd ed.). Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press. pp. 93:124. ISBN 978-0-19-023518-5. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Talukdar, Mohammad Habibur Rahman, ed. (2009) [First published 1987]. Memoirs of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy with a Brief Account of His Life and Work (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-547722-1.

Suhrawardy joined the Proja-League Coalition government that Fazlul Huq formed in April 1937 as Minister for Labour and Commerce.

- Keneally, Thomas (2011). Three Famines: Starvation and Politics. PublicAffairs. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-61039-065-1.

- Mukerjee, Madhusree (2011). Churchill's Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II. Edington, UK: Basic Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-465-02481-0. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Prasad, Rajendra (2010) [First published 1946]. Autobiography. Delhi, India: Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-306881-5. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Chatterji, Joya (2002). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-521-52328-8. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Dowlah, Caf (2016). The Bangladesh Liberation War, the Sheikh Mujib Regime, and Contemporary Controversies. Indiana, U.S.: Lexington Books. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-4985-3419-2. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi (2014). The Defining Moments in Bengal: 1920–1947. Oxford, Eng. UK.: Oxford University Press. p. Contents. ISBN 978-0-19-908934-5. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Ahmed, Wakil. "United Independent Bengal Movement=". Banglapedia. Bangladesh Asiatic Society. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Kabir, Nurul (1 September 2013). "Colonialism, politics of language and partition of Bengal PART XVI". New Age. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present (1st ed.). Delhi, India: APH Publishing. ISBN 9788176484695. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Fraser, Bashabi (2008). Bengal Partition Stories: An Unclosed Chapter. Anthem Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-84331-225-3.

- Panigrahi, Devendra (2004). India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat. Routledge. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-135-76812-6.

- "Programme for Direct Action Day". Star of India. 13 August 1946.

- Chatterji, Joya (1994). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 239. ISBN 978-0-521-41128-8.

Hindu culpability was never acknowledged. The Hindu press laid the blame for the violence upon the Suhrawardy Government and the Muslim League.

- Sengupta, Debjani (2006). "A City Feeding on Itself: Testimonies and Histories of 'Direct Action' Day" (PDF). In Narula, Monica (ed.). Turbulence. Serai Reader. Volume 6. The Sarai Programme, Center for the Study of Developing Societies. pp. 288–295. OCLC 607413832.

- L/I/1/425. The British Library Archives, London.

- Burrows, Frederick (1946). Report to Viceroy Lord Wavell. The British Library IOR: L/P&J/8/655 f.f. 95, 96–107.

- Tsugitaka, Sato (2000). Muslim Societies: Historical and Comparative Aspects. Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-415-33254-5.

- Das, Suranjan (2012). "Calcutta Riot, 1946". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Das, Suranjan (May 2000). "The 1992 Calcutta Riot in Historical Continuum: A Relapse into 'Communal Fury'?". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (2): 281–306. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0000336X. JSTOR 313064.

- Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2004). The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932–1947: Contour of Freedom. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-415-32889-0.

The immediate provocation of a mass scale riot was certainly the afternoon League meeting at the Ochterlony Monument ... Major J. Sim of the Eastern Command wrote, 'there must have [been] 100,000 of them ... with green uniform of the Muslim National Guard' ... Suhrawardy appeared to have incited the mob ... As the Governor also mentioned, 'the violence on a wider scale broke out as soon as the meeting was over', and most of those who indulged in attacking Hindus ... were returning from [it].

- "Direct Action". Time. 26 August 1946. p. 34. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

Moslem League Boss Mohamed Ali Jinnah had picked the 18th day of Ramadan for "Direct Action Day" against Britain's plan for Indian independence (which does not satisfy the Moslems' old demand for a separate Pakistan).

- Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2004). The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932–1947: Contour of Freedom. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-415-32889-0.

Having seen the reports from his own sources, he [Jinnah] was persuaded later, however, to accept that the 'communal riots in Calcutta were mainly started by Hindus and ... were of Hindu origin.'

- Chatterji, Joya (1994). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-521-41128-8.

Both sides in the confrontation came well-prepared for it ... Suhrawardy himself bears much of the responsibility for this blood-letting since he issued an open challenge to the Hindus and was grossly negligent ... in his failure to quell the rioting ... But Hindu leaders were also deeply implicated.

- "National Archives of the UK".

- Roy, Tathagata (25 June 2014). The Life & Times of Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789350488812.

- "The Foreshadowing of Bangladesh: Bengal Muslim League and Muslim Politics: 1906–1947". The University Press Limited. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2009). Decolonization in South Asia: Meanings of Freedom in Post-independence West Bengal, 1947–52. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-01824-6.

- Mukhopadhay, Keshob. "An interview with prof. Ahmed sharif". News from Bangladesh. Daily News Monitoring Service. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Wolpert, Stanley (15 April 2001). "First Chapter: Gandhi's Passion". The New York Times.

- Harun, Shamsul Huda (2001). The Making Of The Prime Minister H.S. Suhra Wardy Inan Anagram Polity 1947–1958. Institute of Liberation Bangabandhu and Bangladesh Studies, National University. p. 23. ISBN 9789847830124.

- Kaushik, S. L.; Patnayak, Rama (1995). Modern Governments and Political Systems: governments and politics in South Asia. India: Mittal Publications. p. 284. ISBN 9788170995920. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Redclift, Victoria (2013). Statelessness and Citizenship: Camps and the Creation of Political Space. UK: Routledge. pp. 1968–1969. ISBN 978-1-136-22031-9.

- "Constituent Assembly of Pakistan Debates: Official Report". Parliament of Pakistan. 1 (1). 1955.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2015). The Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience (2nd ed.). Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan: Oxford University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-19-023518-5. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "West Pakistan Established through One Unit". Story of Pakistan. June 2003. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Grover, Verinder; Arora, Ranjana (1997). Pakistan, Fifty Years of Independence: Independence and beyond: the fifty years, 1947–97. Deep & Deep. p. 265. ISBN 9788171009244.

- Mir, Hamid (9 June 2011). "A Hope is still alive..." Hamid Mir.... Penmanship. Hamid Mir. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- The New International Year Book: A Compendium of the World's Progress for the Year 1956. Funk & Wagnalls. 1957.

- "Prime Minister of Pakistan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy › Page 1". Fold3. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- General Survey (2002). Far East and Australasia: Pakistan. Berlin, Germany: Europa Publications. pp. 1657 onwards. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- Hiro, Dilip (2015). The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan (1st ed.). New York City: PublicAffairs. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-56858-734-9.

- Banerjee, Sumanta (7 August 1982). "Bangladesh's Marxist-Leninists: I". Economic and Political Weekly. 17 (32): 1267–1268. JSTOR 4371213.

- Ram, Raghunath (1985). Super Powers and Indo-Pakistani Sub-continent: Perceptions and Policies. New Delhi: Raaj Prakashan. p. 196. OCLC 461951628.

- Balouch, Akhtar (21 July 2015). "The political victimisation of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Burke, S. M. (1974). Mainsprings of Indian and Pakistani Foreign Policies. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-4529-1071-0.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey (1962). Survey of International Affairs 1956–1958. p. 142.

- Hamid Hussain. "Tale of a love affair that never was: United States-Pakistan Defence Relations". Defence Journal of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2016). The Pakistan Paradox: Instability And Resilience (1st ed.). UK: Random House. p. Contents. ISBN 9788184007077.

- "Resignation of Suhrawardy". Story of Pakistan. June 2003. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- "Suhrawardy and the resignation". Story of Pakistan. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Nair, M. Bhaskaran (1990). Politics in Bangladesh: A Study of Awami League, 1949–58. India: Northern Book Centre. p. 105. ISBN 9788185119793. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "Noor Jehan Begum vs Eugene Tiscenko on 3 January, 1941". Indiankanoon.org. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "Pakistani Politicians: The ones you don't know much about". Gupshup (Forum thread).

In 1940, Suhrawardy married Vera Tiscenko, a former actress of the Moscow Arts Theater. They divorced in 1951. Their only son, Rashid, was brought up in England, where he pursued a career as a professional actor.

- New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Stanislavski Revisited, Broadcast on WNYC AM NYC, 18 July 1976, LT-10 3099

- "Huseyn S. Suhrawardy Is Dead; Ex-Prime Minister of Pakistan; Holder of Post in '56–57 Was Jailed in 1962 as Security Risk—Opposed to Ayub A Link With the West Visited the U.S. Toured With Gandhi". The New York Times. 6 December 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Khayaban-e-Suhrwardy". Google Maps. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Listeners name 'greatest Bengali'". BBC News. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

Further reading

- Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy: A Biography by Begum Shaista Ikramullah (Oxford University Press, 1991)

- Freedom at Midnight by Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins

- Gandhi's Passion by Stanley Wolpert (Oxford University Press)

- The Last Guardian: Memoirs of Hatch-Barnwell, ICS of Bengal by Stephen Hatch-Barnwell (University Press Limited, 2012)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. |

- Works by or about Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy at Internet Archive

- Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy of Pakistan on Face the Nation, 14 July 1957

- The Complete Politician, an article published in Time on Suhrawardy on 24 September 1956

- Suhrawardy Becomes Prime Minister

- Chronicles Of Pakistan

- Glimpses on Suhrawardy, an article published on The Daily Star on 23 June 2009

- Suhrawardy meets Eisenhower, video footage from British Pathé

- Speech by Suhrawardy on Kashmir, video footage from British Pathé

- Commonwealth Ministers at No 10, video footage from British Pathé

| Preceded by Chaudhry Muhammad Ali |

Prime Minister of Pakistan 1956–1957 |

Succeeded by Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar |

| Minister of Defence 1956–1957 |

Succeeded by Mian Mumtaz Daultana |