History of Shia Islam

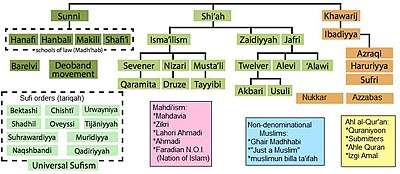

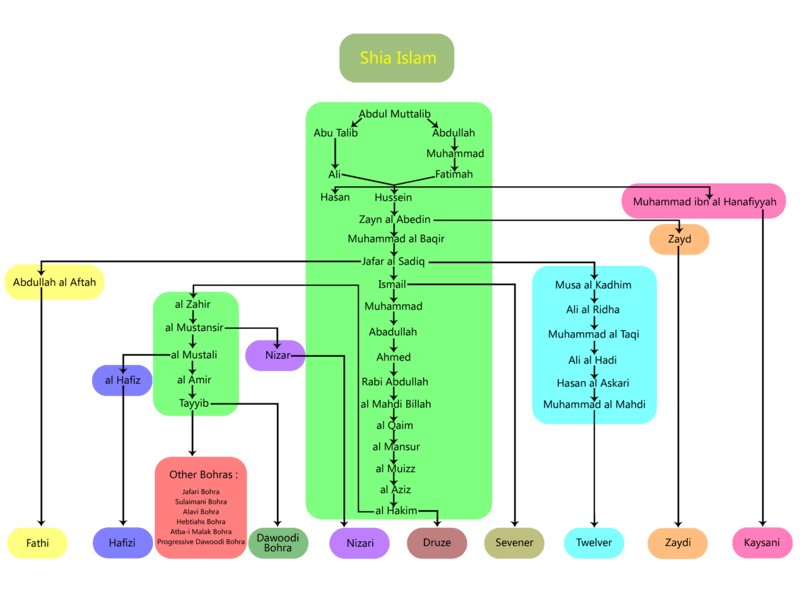

Shi‘a Islam, also known as Shi‘ite Islam or Shi‘ism, is the second largest branch of Islam after Sunni Islam. Shias adhere to the teachings of Muhammad and the religious guidance of his family (who are referred to as the Ahl al-Bayt) or his descendants known as Shia Imams. Muhammad's bloodline continues only through his daughter Fatima Zahra and cousin Ali who alongside Muhammad's grandsons comprise the Ahl al-Bayt. Thus, Shias consider Muhammad's descendants as the true source of guidance. Shia Islam, like Sunni Islam, has at times been divided into many branches; however, only three of these currently have a significant number of followers, and each of them has a separate trajectory.

| Part of a series on Islam Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs and practices |

|

|

Holy women |

|

|

From a political viewpoint the history of the Shia was in several stages. The first part was the emergence of the Shia, which starts after Muhammad's death in 632 and lasts until Battle of Karbala in 680. This part coincides with the Imamah of Ali, Hasan ibn Ali and Hussain. The second part is the differentiation and distinction of the Shia as a separate sect within the Muslim community, and the opposition of the Sunni caliphs. This part starts after the Battle of Karbala and lasts until the formation of the Shia states about 900. During this section Shi'ism divided into several branches. The third section is the period of Shia states. The first Shia state was the Idrisid dynasty (780–974) in Maghreb. Next was the Alavid dynasty (864–928) established in Mazandaran (Tabaristan), north of Iran. These dynasties were local, but they were followed by two great and powerful dynasties. The Fatimid Dynasty formed in Ifriqiya in 909, and ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Egypt and the Levant until 1171. The Buyid dynasty emerged in Daylaman, north of Iran, about 930 and then ruled over central and western parts of Iran and Iraq until 1048. In Yemen, Imams of various dynasties usually of the Zaidi sect established a theocratic political structure that survived from 897 until 1962.

From Saqifa to Karbala

Muhammad began preaching Islam at Mecca before migrating to Medina, from where he united the tribes of Arabia into a singular Arab Muslim religious polity. With Muhammad's death in 632, disagreement broke out over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community. While Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law, and the rest of Muhammad's close family were washing his body for burial, the tribal leaders of Mecca and Medina held a secret gathering at Saqifah to decide who would succeed Muhammad as head of the Muslim state, disregarding what the earliest Muslims, the Muhajirun, regarded as Muhammad's appointment of Ali as his successor at Ghadir Khumm. Umar ibn al-Khattab, a companion of Muhammad and was first person to congratulate Ali on event of Ghadeer, nominated Abu Bakr. Others, after initial refusal and bickering, settled on Abu Bakr who was made the first caliph. This choice was disputed by Muhammad's earliest companions, who held that Ali had been designated his successor. According to Sunni accounts, Muhammad died without having appointed a successor, and with a need for leadership, they gathered and voted for the position of caliph. Shi'a accounts differ by asserting that Muhammad had designated Ali as his successor on a number of occasions, including on his death bed. Ali was supported by Muhammad's family and the majority of the Muhajirun, the initial Muslims, and was opposed by the tribal leaders of Arabia who included Muhammad's initial enemies, including, naturally, the Banu Umayya.[1] Abu Bakr's election was followed by a raid on Ali's house led by Umar and Khalid ibn al-Walid (see Umar at Fatimah's house). [2]

The succession to Muhammad is an extremely contentious issue. Muslims ultimately divided into two branches based on their political attitude towards this issue, which forms the primary theological barrier between the two major divisions of Muslims: Sunni and Shi'a, with the latter following Ali as the successor to Muhammad. The two groups also disagree on Ali's attitude towards Abu Bakr, and the two caliphs who succeeded him: Umar (or `Umar ibn al-Khattāb) and Uthman or (‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān). Sunnis tend to stress Ali's acceptance and support of their rule, while the Shi'a claims that he distanced himself from them, and that he was being kept from fulfilling the religious duty that Muhammad had appointed to him. The Sunni Muslims say that if Ali was the rightful successor as ordained by God Himself, then it would have been his duty as the leader of the Muslim nation to make war with these people (Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman) until Ali established the decree. Shia claim, however, that Ali did not fight Abu Bakr, Umar or Uthman, because firstly he did not have the military strength and if he decided to, it would have caused a civil war amongst the Muslims, which was still a nascent community throughout the Arab world.[3]

Differentiation and distinction

Shia Islam and Sunnism split in the aftermath of the death of Muhammad based on the politics of the early caliphs. Due to the Shi'a belief that Ali should have been the first caliph, the three caliphs that preceded him, Abu Bakr, Umar, and Usman, were considered illegitimate usurpers. Because of this, any hadith that were narrated by these three caliphs (or any of their supporters) were not accepted by Shi'a hadith collectors.

Due to this, the number of hadith accepted by Shi'a is far less than the hadith accepted by Sunnis, with many of the non-accepted hadith being ones that had to deal with integral aspects of Islam, such as prayer and marriage. In the absence of a clear hadith for a situation, the Shi'a prefer the sayings and actions of the Imams (Prophet's family members) on the similar level as the hadith of the Prophet himself over other ways, which in turn led to the theological elevation of the Imams as being infallible.[4][5]

Division into branches

Ancestors and the family tree

| Quraysh tribe | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abd Manaf ibn Qusai | Ātikah bint Murrah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Abd Shams | Barra | Hala | Muṭṭalib | Hashim | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Umayya ibn Abd Shams | ‘Abd al-Muttalib | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Harb | Abu al-'As | ʿĀminah | ʿAbd Allāh | Abî Ṭâlib | Hamza | Al-‘Abbas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ʾAbī Sufyān ibn Harb | Al-Hakam | Affan ibn Abi al-'As | MUHAMMAD (Family tree) | Khadija bint Khuwaylid | `Alî al-Mûrtdhā | Khawlah bint Ja'far | ʿAbd Allâh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muʿāwiyah | Marwan I | Uthman ibn Affan | Ruqayyah | Fatima Zahra | Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah | ʿAli bin ʿAbd Allâh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Umayyad Caliphate | Uthman ibn Abu-al-Aas | Hasan al-Mûjtabâ | Husayn bin Ali (Family tree) | al-Mukhtār ibn Abī ‘Ubayd Allah al-Thaqafī (Abû‘Amra`Kaysan’îyyah) | Muhammad "al-Imâm" (Abbasids) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Divisions and madh'habs

| Quraysh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'Abd Manaf | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'Abd Shams | Hashim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Umayya | 'Abdu'l-Muttalib | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Harb | Ab'l-As | 'Abdu'llah | Abu Talib | al-'Abbas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abu sufyan | al-Hakam | Affan | Fatima | 'Ali | 'Abbasid Caiphs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mu'awiya | Marwan | 'Uthman | Hasan | Husain | Muhammad ibn Hanafiyya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Early Ummayad Caliphs | Later Ummayad Caliphs | Idrisids in N. Africa, some Zaydi Imams | 'Ali Zaynu'l-Abidin | Kaysaniyya Sect | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad, al-Baqir | Zayd | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jafar, as-Sadiq | Zaydi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isma'il | Musa, al-Kazim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt | 'Ali, ar-Rida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isma'ili Shi'ism | Muhammad, al-Taqi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'Ali, al-Hadi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hasan al-Askari | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imam Mahdi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ithnā‘ashari (twelvers) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Twelvers history

Imams era

Occultation era

Ismaili history

Old Da'vat

New Da'vat

Zaidiyya history

Other sects

Qarmatians

Alevis

Alawism

Shia empires

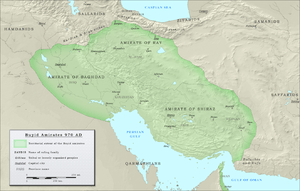

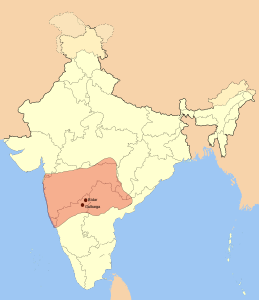

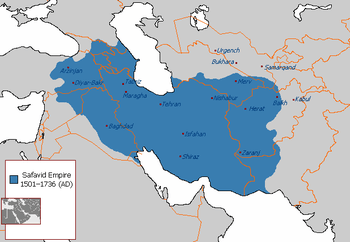

The following pictures are examples of some of the Shia Islamic empires through history:

Buyid empire in 970

Buyid empire in 970- Extent of Shia rule under the Fatimids

- Extent of Shia rule under the Uqaylids

- Extent of Shia rule under the Idrisids

- Extent of Shia rule under the Ilkhanates

Extent of Shia rule under the Bahmani Sultanate

Extent of Shia rule under the Bahmani Sultanate Extent of Shia rule under the Safavid dynasty

Extent of Shia rule under the Safavid dynasty

Notes

- Chirri, Mohammad (1982). The Brother of the Prophet Mohammad. Islamic Center of America, Detroit, MI. Alibris ID 8126171834.

- See:

- Holt (1977a), p.57

- Lapidus (2002), p.32

- Madelung (1996), p.43

- Tabatabaei (1979), p.30–50

- Sahih Bukhari

- Alkhateeb, Firas (2014). Lost Islamic History. London: Hurst Publishers. p. 85. ISBN 9781849043977.

- Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East: A History. Boston: McGraw Hill. p. 90. ISBN 0072442336.

- "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. October 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

Of the total Muslim population, 11-12% are Shia Muslims and 87-88% are Sunni Muslims.

- "Religions". CIA World Factbook.

- "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009.

See also

- Abdullah ibn Saba

- Historical Shi'a-Sunni relations

References

- Holt, P. M.; Bernard Lewis (1977a). Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291364.

- Lapidus, Ira (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521779333.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1996). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521646960.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Seyyed Hossein Nasr (trans.). Suny press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.