Heysel Stadium disaster

The Heysel Stadium disaster (French: [ɛizɛl]; Dutch: [ˈɦɛizəl] (![]()

| Date | 29 May 1985 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Heysel Stadium |

| Location | Brussels, Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°53′45″N 4°20′3″E |

| Cause | Riot |

| Filmed by | European Broadcasting Union |

| Participants | Supporters of Liverpool and Juventus |

| Outcome | English clubs banned from European competition for five years; Liverpool for six years |

| Deaths | 39 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 600 |

| Arrests | 34 |

| Convicted | Several top officials, police captain Johan Mahieu, and 14 Liverpool fans convicted of manslaughter |

Approximately an hour before the Juventus–Liverpool final was due to kick off, Liverpool supporters charged at Juventus fans and breached a fence that was separating them from a "neutral area." The cause of the rampage is disputed: Many accounts attribute blame to the Italian fans for sparking the violence, but this claim is contested by other eye-witnesses and has been criticized for being unsubstantiated.[2] Juventus fans ran back on the terraces and away from the threat into a concrete retaining wall. Fans already standing near the wall were crushed; eventually the wall collapsed, allowing others to escape.[3] Many people climbed over to safety, but many others died or were badly injured. The game was played despite the disaster, with Juventus winning 1–0.[4]

The tragedy resulted in all English football clubs being placed under an indefinite ban by UEFA from all European competitions (lifted in 1990–91), with Liverpool being excluded for an additional three years, later reduced to one,[5] and 14 Liverpool fans found guilty of manslaughter and each sentenced to three years' imprisonment. The disaster was later described as "the darkest hour in the history of the UEFA competitions".[6]

Events leading up to the disaster

In May 1985, Liverpool were the defending European Champions' Cup winners, having won the competition after defeating Roma in the penalty shootout in the final of the previous season. Again they would face Italian opposition, Juventus, who had won, unbeaten, the 1983–84 Cup Winners' Cup. Juventus had a team consisting of many of Italy's 1982 FIFA World Cup winning team—who played for Juventus for many years—and their playmaker Michel Platini was considered the best footballer in Europe, being named Footballer of The Year by France Football magazine for the second year in a row in December 1984. Both teams were placed in the two first positions in the UEFA club ranking at the end of the last season[7] and were regarded by the specialist press as the best two sides on the continent at the time.[8] Both teams had contested the 1984 European Super Cup four months before, finishing with victory for the Italian side by 2–0.

Despite its status as Belgium's national stadium, Heysel was in a poor state of repair by the time of the 1985 European Final. The 55-year-old stadium had not been sufficiently maintained for several years, and large parts of the stadium were literally crumbling. For example, the outer wall had been made of cinder block, and fans who did not have tickets were seen kicking holes in it to get in.[9] Liverpool players and fans later said that they were shocked at Heysel's abject condition, despite reports from Arsenal fans that the ground was a "dump" when Arsenal had played there a few years earlier. They were also surprised that Heysel was chosen despite its poor condition, especially since Barcelona's Camp Nou and Santiago Bernabéu in Madrid were both available. Juventus president Giampiero Boniperti and Liverpool CEO Peter Robinson urged UEFA to choose another venue, claiming that Heysel was not in any condition to host a European Final, especially a European Final involving two of the largest and most powerful clubs in Europe. However, UEFA refused to consider a move.[10][11] It was later discovered that UEFA's inspection of the stadium lasted just thirty minutes.[12]

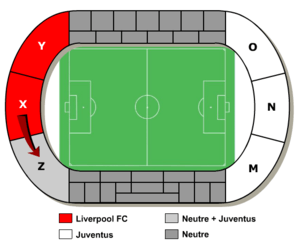

The stadium was crammed with 58,000–60,000 supporters, with more than 25,000 for each team. The two ends behind the goals comprised all-standing terraces, each end split into three zones. The Juventus end was O, N, and M and the Liverpool end was X, Y, and Z as deemed by the Belgian court after the disaster. However, the tickets for the Z section were reserved for neutral Belgian fans in addition to the rest of the stadium. This meant the Juventus fans had more sections than the Liverpool fans with the Z section occupied by neutrals which is thought to have heightened prematch tensions. The idea of the large neutral area was opposed by both Liverpool and Juventus,[13] as it would provide an opportunity for fans of both clubs to obtain tickets from agencies or from ticket touts outside the ground and thus create a dangerous mix of fans.

At the time, Brussels, like the rest of Belgium, already had a large Italian community, and many expatriate Juventus fans bought the section Z tickets.[14] Added to this, many tickets were bought up and sold by travel agents, mainly to Juventus fans. A small percentage of the tickets ended up in the hands of Liverpool fans.

Confrontation

At approximately 7 p.m. local time, an hour before kick-off, the trouble started.[15] The Liverpool and Juventus supporters in sections X and Z stood merely yards apart. The boundary between the two was marked by temporary chain link fencing and a central thinly policed no-man's land.[16] Hooligans began to throw stones across the divide, which they were able to pick up from the crumbling terraces beneath them.

As kick-off approached, the throwing became more intense. Several groups of Liverpool hooligans broke through the boundary between section X and Z, overpowered the police, and charged at the Juventus fans. The fans began to flee toward the perimeter wall of section Z. The wall could not withstand the force of the fleeing Juventus supporters and a lower portion collapsed.

In retaliation for the events in section Z, many Juventus fans rioted at their end of the stadium. They advanced down the stadium running track to help other Juventus supporters, but police intervention stopped the advance. A large group of Juventus fans fought the police with rocks, bottles, and stones for two hours. One Juventus fan was also seen firing a starting gun at Belgian police.[17]

The match

Despite the scale of the disaster, UEFA officials, Belgian Prime Minister Wilfried Martens, Brussels Mayor Hervé Brouhon, and the city's police force felt that abandoning the match would have risked inciting further trouble and violence, and the match eventually kicked off after the captains of both sides spoke to the crowd and appealed for calm.[18]

Juventus won the match 1–0 thanks to a penalty scored by Michel Platini, awarded by Swiss referee Daina for a foul against Zbigniew Boniek.[19]

At the end of the game the trophy was given in front of the stadium's Honor Stand by the confederation president Jacques Georges to Juventus captain Gaetano Scirea. Due to collective hysteria generated by the massive invasion of the pitch by journalists and fans at the end of the match,[20] and the chants of fans of both teams in the stands,[21] some Italian club players celebrated the title in the middle of the pitch among them and in front of their fans in the M section, while some Liverpool players applauded their fans between the X and Z sections, the stadium's section affected.[22]

Aftermath

Criminal proceedings

The blame for the incident was laid on the fans of Liverpool FC. On 30 May official UEFA observer Gunter Schneider said, "Only the Liverpool fans were responsible. Of that there is no doubt." UEFA, the organiser of the event, the owners of Heysel Stadium and the Belgian police were investigated for culpability. After an 18-month investigation, the dossier of top Belgian judge Marina Coppieters was finally published. It concluded that blame should rest solely with the Liverpool fans.

The British police undertook a thorough investigation to bring to justice the perpetrators. Some 17 minutes of film and many still photographs were examined. TV Eye produced an hour-long programme featuring the footage and the British press also published the photographs.

A total of 34 people were arrested and questioned with 26 Liverpool fans being charged with manslaughter—the only extraditable offence applicable to events at Heysel. An extradition hearing in London in February–March 1987 ruled all 26 were to be extradited to stand trial in Belgium for the death of Juventus fan Mario Ronchi. In September 1987 they were extradited and formally charged with manslaughter applying to all 39 deaths and further charges of assault. Initially, all were held at a Belgian prison but over the subsequent months judges permitted their release as the start of the trial was further delayed.

The trial eventually began in October 1988, with three Belgians also standing trial for their role in the disaster: Albert Roosens, the head of the Belgian Football Association, for allowing tickets for the Liverpool section of the stadium to be sold to Juventus fans; and two police chiefs—Michel Kensier and Johann Mahieu—who were in charge of policing at the stadium that night. Two of the 26 Liverpool fans were in custody in Britain at the time and stood trial later. In April 1989, 14 fans were convicted and given three-year sentences, that were half suspended for five years, allowing them to return to the UK.[23] One man who was acquitted was Ronnie Jepson, who would go on to make 414 appearances over a 13 year career in the English Football League.[24] After Belgian prosecutors appealed the sentences as too lenient, an appeal took place in Spring 1990 that increased the sentences of 11 fans (to four or five years), with two having their sentences upheld and one being acquitted.

Stadium investigation

Gerry Clarkson, Deputy Chief of the London Fire Brigade, was sent by the British Government to report on the condition of the stadium. He concluded that the deaths were "...Attributable very, very largely to the appalling state of [the] stadium."[25][26] He discovered that the crush barriers were unable to contain the weight of the crowd and had the reinforcement in the concrete exposed, the wall's piers had been built the wrong way around and that there was a small building at the top of the terrace that contained long plastic tubing underneath.[25] His report was never used in any inquiry for the disaster.[25]

English club ban

Pressure mounted to ban English clubs from European competition. On 31 May 1985, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher asked the FA to withdraw English clubs from European competition before they were banned,[27] but two days later, UEFA banned English clubs for "an indeterminate period of time." On 6 June, FIFA extended this ban to all worldwide matches, but this was modified a week later to allow friendly matches outside of Europe to take place. In December 1985, FIFA announced that English clubs were also free to play friendly games in Europe, though the Belgian government banned any English clubs playing in their country.

Though the English national team was not subjected to any bans, English club sides were banned indefinitely from European club competitions, with Liverpool being provisionally subject to a further three years suspension as well. In April 1990, following years of campaigning from the English football authorities, UEFA confirmed the reintroduction of English clubs (with the exception of Liverpool) into its competitions from the 1990–91 season onward; in April 1991 UEFA's Executive Committee voted to allow Liverpool back into European competition from the 1991–92 season onward, a year later than their compatriots, but two years earlier than initially foreseen. In the end, all English clubs served a five-year-ban, while Liverpool were excluded for six years.

According to former Liverpool striker Ian Rush, who signed with Juventus a year later, he saw pronounced improvement in the institutional relationships between both the clubs and their fans during his career in Italy.[10]

England's UEFA Coefficient

Prior to the introduction of the ban, England were ranked first in the UEFA coefficient ranking due to the performance of English clubs in European competition in the previous five seasons.[28] Throughout the ban, England's points were kept in the ranking until they would have naturally been replaced.

The places vacated by English clubs in the UEFA Cup were reallocated to the best countries who would usually only have two spots in the competition—countries ranked between ninth and twenty-first. For the 1985–86 UEFA Cup, the Soviet Union, France, Czechoslovakia, and the Netherlands were granted an additional spot each, while in 1986–87, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, France, and East Germany were the recipients. The 1987–88 saw Portugal, Austria, and Sweden gain an additional place, with Sweden and Yugoslavia gaining the places for the 1988–89 competition. The final year of the English ban, 1989–90 saw Austria receive a spot, while a play-off round was played between a French and a Yugoslav side for the final space—due to the two countries having the same number of points in the ranking.[29]

England was removed from the rankings in 1990 due to having no points.[30] England did not return to the top of the coefficient rankings until 2008.[31]

Banned clubs

The following clubs were denied entry to European competitions during this period:

| Seasons | European Cup | European Cup Winners' Cup | UEFA Cup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985–86 | Everton | Manchester United (4th) | Liverpool (2nd) Tottenham Hotspur (3rd) Southampton (5th) Norwich City (League Cup winners; 20th) |

| 1986–87 | Liverpool | Everton (2nd) | West Ham United (3rd) Manchester United (4th) Sheffield Wednesday (5th) Oxford United (League Cup winners; 18th) |

| 1987–88 | Everton | Coventry City (10th) | Liverpool (2nd) Tottenham Hotspur (3rd) Arsenal (4th; League Cup winners) Norwich City (5th) |

| 1988–89 | Liverpool | Wimbledon (6th) | Manchester United (2nd) Nottingham Forest (3rd) Everton (4th) Luton Town (League Cup winners; 9th) |

| 1989–90 | Arsenal | Liverpool (2nd) | Nottingham Forest (3rd; League Cup winners) Norwich City (4th) Derby County (5th) Tottenham Hotspur (6th) |

| 1990–91 | Liverpool |

The number of places available to English clubs in the UEFA Cup would however have been reduced had English teams been eliminated early in the competition. By the time of the re-admittance of all English clubs except Liverpool in 1990–91, England was only granted one UEFA Cup entrant (awarded to the league runners-up); prior to the ban, they had four entry slots, a number not awarded to England again until the 1994–95 UEFA Cup.

Welsh clubs playing in the English league system, who could qualify for the European Cup Winners' Cup via the Welsh Cup, were unaffected by the ban. Bangor City (1985–86)[note 1], Wrexham (1986–87), Merthyr Tydfil (1987–88), Cardiff City (1988–89), and Swansea City (1989–90) all competed in the Cup Winners' Cup during the ban on English clubs, despite playing in the English league system.

In the meantime, many other clubs missed out on a place in the UEFA Cup due to the return of English clubs to European competitions only being gradual—in 1990, the league had no UEFA coefficient points used to calculate the number of teams, and even though Manchester United won the Cup Winners' Cup in the first season of returning in 1991, it took several more years for England to build up the points to the previous level, due to the coefficient being calculated over a five-year period and there being a one-year delay between the publication of the rankings and their impact on club allocation.

Liverpool's additional year of exclusion from Europe meant that there was no English representation in the 1990–91 European Cup, as they were 1989–90 Football League First Division champions. Due to the weak coefficient, Football League Cup winners Nottingham Forest also missed out on UEFA Cup places in 1990–91, along with Tottenham Hotspur and Arsenal.

The teams who missed out on the 1991–92 UEFA Cup, for the same reason were Sheffield Wednesday, Crystal Palace and Leeds United. Arsenal and Manchester City were unable to take part for the 1992–93 competition. For 1993–94, Blackburn Rovers and Queens Park Rangers would have qualified. Leeds United missed out in 1994–95 and initially 1995–96, though they qualified for the latter via the new UEFA Fair Play ranking. England briefly returned to the top six of the coefficient rankings and regained its fourth berth in the UEFA Cup for the 1996–97 season, however Everton missed out on a Fair Play berth that season[note 2]. England dropped out of the top six the following two seasons and returned to having three berths in the UEFA Cup. Though by this point England's coefficient was no longer directly affected by the ban due to it being outside of the five-year window, their coefficient continued to be affected by years of under-representation in Europe. As a result, Aston Villa missed out via their league position for 1997–98 and 1998–99 but qualified for both through Fair Play. England reached the top six of the coefficient ranking from 1999–2000, however expansion of the UEFA Champions League that season meant that top-ranked associations were given three berths for the UEFA Cup from then on, whilst associations ranked seventh and eighth were given four berths.

Impact on stadiums

After Heysel, English clubs began to impose stricter rules intended to make it easier to prevent troublemakers from attending domestic games, with legal provision to exclude troublemakers for three months introduced in 1986, and the Football (Offences) Act introduced in 1991.

Serious progress on legal banning orders preventing foreign travel to matches was arguably not made until the violence involving England fans (allegedly mainly involving neo-Nazi groups, such as Combat 18) at a match against Ireland on 15 February 1995 and violent scenes at the 1998 FIFA World Cup. Rioting at UEFA Euro 2000 saw introduction of new legislation and wider use of police powers—by 2004, 2,000 banning orders were in place, compared to fewer than 100 before Euro 2000.[32][33]

The main reforms to English stadiums came after the Taylor Report into the Hillsborough disaster in which 96 people died in 1989. All-seater stadiums became a requirement for clubs in the top two divisions while pitch-side fencing was removed and closed-circuit cameras have been installed. Fans who misbehave can have their tickets revoked and be legally barred from attending games at any English stadium.

The Heysel Stadium itself continued to be used for hosting athletics for almost a decade, but no further football matches took place in the old stadium. In 1994, the stadium was almost completely rebuilt as the King Baudouin Stadium. On 28 August 1995 the new stadium welcomed the return of football to Heysel in the form of a friendly match between Belgium and Germany. It then hosted a major European final on 8 May 1996 when Paris Saint-Germain defeated Rapid Vienna 1–0 to win the Cup Winners' Cup.

Commemorations

In 1985, a memorial was presented to the victims at the Juventus headquarters in Piazza Crimea, Turin. The monument includes an epitaph written by Torinese journalist Giovanni Arpino. Since 2001 it has been situated in front of the current club's headquarters in Corso Galileo Ferraris.[34]

In 1986, the band Revolting Cocks, founded in part by Al Jourgensen of Ministry, released a song by the name of "38" on the album Big Sexy Land, in commemoration of the deaths.

A memorial service for those killed in the disaster was held before Liverpool's match with Arsenal at Anfield on 18 August 1985, their first fixture after the disaster. However, according to The Sydney Morning Herald, it was "drowned out" by chanting.[35]

In 1991, a memorial monument for the 39 victims of the disaster, the only one on Italian soil, was inaugurated in Reggio Emilia, the hometown of the victim Claudio Zavaroni, in front of Stadio Mirabello: every year the committee "Per non dimenticare Heysel" (In order not to forget Heysel) holds a ceremony on 29 May with relatives of the victims, representatives of Juventus, survivors and various supporters clubs from various football clubs, including Inter Milan, AC Milan, Reggiana and Torino.[36]

During Euro 2000, members of the Italian team left flowers on the site, in honour of the victims.

On 29 May 2005, a £140,000 sculpture was unveiled at the new Heysel stadium, to commemorate the disaster. The monument is a sundial designed by French artist Patrick Rimoux and includes Italian and Belgian stone and the poem "Funeral Blues" by Englishman W. H. Auden to symbolise the sorrow of the three countries. Thirty-nine lights shine, one for each who died that night.[37]

Juventus and Liverpool were drawn together in the quarter-finals of the 2005 Champions League, their first meeting since Heysel. Before the first leg at Anfield, Liverpool fans held up placards to form a banner saying "amicizia" ("friendship" in Italian). Many of the Juventus fans applauded the gesture, although a significant number chose to turn their backs on it.[38] In the return leg in Turin, Juventus fans displayed banners reading Easy to speak, difficult to pardon: Murders and 15-4-89. Sheffield. God exists, the latter a reference to the Hillsborough disaster, in which 96 Liverpool fans were killed in a crush. A number of Liverpool fans were attacked in the city by Juventus ultras.[39]

British composer Michael Nyman wrote a piece called "Memorial" which was originally part of a larger work of the same name written in 1985 in memory of the Juventus fans who died at Heysel Stadium.

On Wednesday 26 May 2010, a permanent plaque was unveiled on the Centenary Stand at Anfield to honour the Juventus fans who died 25 years earlier. This plaque is one of two permanent memorials to be found at Anfield, along with one for the 96 fans killed in the Hillsborough disaster in 1989.

In May 2012, a Heysel Memorial was unveiled in the J-Museum at Turin. There is also a tribute to the disaster's victims in the club's Walk of Fame in front of the Juventus Stadium. Two years later Juventus' officials announced a memorial in the Continassa headquarter.

In February 2014, an exhibition in Turin was dedicated both to the Heysel tragedy and Superga air disaster. The name of the exhibition was "Settanta angeli in un unico cielo – Superga e Heysel tragedie sorelle" (70 angels in the one same heaven – Superga and Heysel sister tragedies) and gathered material from 4 May 1949 and 29 May 1985.[40]

In May 2015, during a Serie A match between Juventus and Napoli at Turin, Juventus fans held up placards to form a banner saying "+39 Rispetto" ("respect +39" in Italian) including the names of the victims of the disaster.[41]

On 12 November 2015 Italian Football Federation (FIGC), Juventus' representatives led by Mariella Scirea and J-Museum president Paolo Garimberti and members of the Italian victims association held a ceremony in front of the Heysel monument in King Baudouin Stadium for the 30th anniversary of the event.[42] The following day, FIGC president Carlo Tavecchio announced the retirement of Squadra Azzurra's number 39 shirt prior to the friendly match between Italy and Belgium.[43]

Deaths

The 39 people killed were 32 Italians (including two minors), four Belgians, two French fans and one from Northern Ireland.[44][45][46]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Notes

- Bangor City finished runners-up of the 1984–85 Welsh Cup to English side Shrewsbury Town, however English teams cannot qualify for the Cup Winners' Cup through the Welsh Cup.

- This was not due to the Heysel Disaster. England were due to be given a Fair Play berth for the 1996–97 UEFA Cup but were denied by UEFA due to Tottenham Hotspur and Wimbledon fielding weakened teams in the 1995 UEFA Intertoto Cup.

See also

References

- "Heysel: Liverpool and Juventus remember disaster that claimed 39 lives". Daily Mirror. 29 May 2012.

- Heysel stadium disaster: ‘I saw the rows of bodies piled high’, The Guardian

- Kelso, Paul (April 2005). "Liverpool still torn over tragedy". The Guardian.

- "Liverpool – History – Heysel disaster". BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- "Heysel, 27 Years On – Book Extract | The Tomkins Times | News, Opinion, Statistics and Discussion about Liverpool FC Football Club". The Tomkins Times. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Quote from UEFA Chief Executive Lars-Christer Olsson in 2004, uefa.com

- "UEFA Team Coefficients 1983/1984". Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- (Falkiner 2012)

- Evans, Tony (5 April 2005). "Our day of shame". The Times. London. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- Enrico Sisti (28 May 2010). "Il calcio cambiò per sempre" (in Italian). la Repubblica. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- "LFC Story 1985". Liverpool Official Website. Archived from the original on 20 May 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- "The Heysel Stadium Disaster". Royal Belgian Football Association. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Ducker, James; Dart, Tom (19 March 2005). "Night of mayhem in Brussels that will never be forgotten". The Times. London. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- Kelso, Paul (2 April 2005). "Liverpool still torn over night that shamed their name". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- "The Heysel disaster". BBC News. 29 May 2000. Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- Hussey, Andrew (3 April 2005). "Lost lives that saved a sport". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- "Italian fan firing a gun at Belgium police". Ottawa Citizen.

- Graham (1985, p. 55)

- "Nie dla Bońka na stadionie Juventusu". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- Reilly, Thomas (1996). "Science and Soccer" (PDF). London: E & FN Spon. pp. 316, 320. ISBN 0-419-18880-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2014.

- James Arangüera (7 June 1985). "Um trófeu para ser esquecido" (in Portuguese). Placar. p. 29.

- Camerani, Francesco (2003). Le verità sull'Heysel. Cronaca di una strage annunciata (in Italian). Taylor & Francis. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-888-7-67623-5.

- Jackson, Jamie (3 April 2005). "The witnesses". The Observer. London. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- Kent, Jeff (1989). Port Vale Promotion Chronicle 1988–1989: Back to Where We Once Belonged!. Witan Books. p. 17. ISBN 0-9508981-3-9.

- The Explosive 80s: How Heysel Changed Football. 23 May 2005. Channel 4, RTÉ.

- Chalmers, Robert. "Remembering the Heysel stadium disaster". GQ. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Thatcher set to demand FA ban on games in Europe". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- "UEFA Country Ranking 1985". kassiesa.home.xs4all.nl. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "UEFA Ranking History". kassiesa.home.xs4all.nl. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "UEFA Country Ranking 1990". kassiesa.home.xs4all.nl. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "UEFA Country Ranking 2008". kassiesa.home.xs4all.nl. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- Crime | Home Office Archived 29 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- [Archived Content] Football disorder | Home Office Archived 18 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Una foto del monumento a Torino" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- "Liverpool fans mar service for riot victims". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 August 1985. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- "Reggio Emilia 1985-2019".

- White, Duncan (30 May 2005). "Anniversary monument honours Heysel dead". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Mixed reactions to Heysel homage". BBC News. 6 April 2005. Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- Moore, Glenn (14 April 2005). "Taunts and trouble mar Juve's attempts to deal with the past". The Independent. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- Heysel and Superga: Juve and Toro's pain finally united in an exhibition Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine -serieaddicted.com

- "EuroBeat: Dortmund farewell Jurgen Klopp, party time for league winners Juventus, Bayern, PSG". Fox Sports. 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- "In memoria delle vittime dell'Heysel" (in Italian). juventus.com. 12 November 2015.

- "Azzurri a Bruxelles 30 anni dopo la tragedia dell'Heysel: le iniziative della FIGC". Vivo Azzurri (in Italian). Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio. 11 November 2015.

- "Heysel stadium disaster film is planned". BBC News. 17 May 2011.

- The 39 victims who died at Heysel Stadium -liverpooldailypost.co.uk

- "Le 39 Vittime della Strage". associazionefamiliarivittimeheysel.it (in Italian). Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Jean-Philippe Leclaire (18 May 2005). Le Heysel: Une tragédie européenne. ISBN 9782702146842. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Il y a trente-deux ans, des Chapellois frappés par le drame du Heysel". lavoixdunord.fr (in French). 2 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Remembering Belfast man Patrick Radcliffe who died in Heysel tragedy". Belfast Telegraph. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

Works cited

- Falkiner, Keith (2012). "A Midfield Maestro". in Emerald Anfield. The Irish and Liverpool FC. Dublin: Hachette Books Ireland. ISBN 978-1-444-74386-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graham, Matthew (1985). Liverpool. Twickenham: Hamlyn Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-600-50254-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Evans, R., & Rowe, M. (2002). For Club and Country: Taking Football Disorder Abroad. Soccer & Society, 3(1), 37. DOI: 10.1080/714004870

- Hopkins, M; Treadwell, J (2014). Football Hooliganism, Fan Behaviour and Crime: Contemporary Issues. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137347978.

- Nash, Rex (2001). "English Football Fan Groups in the 1990s: Class, Representation and Fan Power". Soccer and Society. 2 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1080/714866720.

- Johnes, Martin (2004). "'Heads in the Sand': Football, Politics and Crowd Disasters in Twentieth-Century Britain". Soccer and Society. 5 (2): 134–151. doi:10.1080/1466097042000235173.

- Redhead, Steve (Autumn 2004). "Hit and tell: A review essay on the Soccer Hooligan Memoir". Soccer and Society. 5 (3): 392–403. doi:10.1080/1466097042000279625.

- Williams, John (2006). "'Protect Me From What I Want': Football Fandom, Celebrity Cultures and 'New' Football in England". Soccer and Society. 7 (1): 96–114. doi:10.1080/14660970500355637.

- Frosdick, Steve; Newton, Robert (2006). "The Nature and Extent of Football Hooliganism in England and Wales". Soccer and Society. 7 (4): 403–422. doi:10.1080/14660970600905703.

- Holt, Matthew (2007). "The Ownership and Control of Elite Club Competition in European Football". Soccer and Society. 8 (1): 50–67. doi:10.1080/14660970600989491.

- Redhead, Steve (2007). "This Sporting Life: The Realism of The Football Factory". Soccer and Society. 8 (1): 90–108. doi:10.1080/14660970600989525.

- Spaaij, Ramón (2007). "Football hooliganism as a transnational phenomenon: Past and present analysis: A critique – More specificity and less generality". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 24 (4): 411–431. doi:10.1080/09523360601157156.