UEFA Champions League

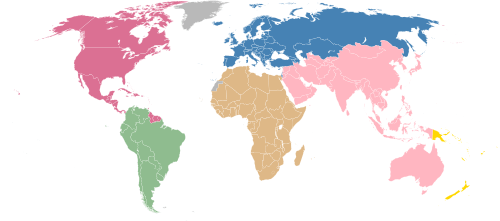

The UEFA Champions League (also known as the European Cup) is an annual club football competition organised by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and contested by top-division European clubs, deciding the competition winners. It is one of the most prestigious football tournaments in the world and the most prestigious club competition in European football, played by the national league champions (and, for some nations, one or more runners-up) of their national associations.

| |

| Founded | 1955 (rebranded in 1992) |

|---|---|

| Region | Europe (UEFA) |

| Number of teams | 32 (group stage) 79 (total) |

| Qualifier for | UEFA Super Cup FIFA Club World Cup |

| Related competitions | UEFA Europa League (2nd tier) UEFA Europa Conference League (planned 3rd tier) |

| Current champions | |

| Most successful club(s) | |

| Television broadcasters | List of broadcasters |

| Website | uefa.com |

Introduced in 1955 as the European Champion Clubs' Cup, it was initially a straight knockout tournament open only to the champion club of each national championship. The competition took on its current name in 1992, adding a round-robin group stage and allowing multiple entrants from certain countries.[1] It has since been expanded, and while most of Europe's national leagues can still only enter their champion, the strongest leagues now provide up to four teams.[2][3] Clubs that finish next-in-line in their national league, having not qualified for the Champions League, are eligible for the second-tier UEFA Europa League competition, and from 2021, teams not eligible for the UEFA Europa League will qualify for a new third-tier competition called the UEFA Europa Conference League.[4]

In its present format, the Champions League begins in late June with a preliminary round, three qualifying rounds and a play-off round, all played over two legs. The six surviving teams enter the group stage, joining 26 teams qualified in advance. The 32 teams are drawn into eight groups of four teams and play each other in a double round-robin system. The eight group winners and eight runners-up proceed to the knockout phase that culminates with the final match in late May or early June.[5] The winner of the Champions League qualifies for the following year's Champions League, the UEFA Super Cup and the FIFA Club World Cup.[6][7] In 2020, the traditional schedule for UEFA matches was disrupted. Those scheduled for May 2020 were postponed due to the coronavirus outbreak, leaving some finals unconcluded.[8]

The competition has been won by 22 clubs, 12 of which have won it more than once.[9] Real Madrid is the most successful club in the tournament's history, having won it 13 times, including its first five seasons. Liverpool are the reigning champions, having beaten Tottenham Hotspur 2–0 in the 2019 final. Spanish clubs have the highest number of victories (18 wins), followed by England (13 wins) and Italy (12 wins). England has the largest number of winning teams, with five clubs having won the title.

History

The first pan-European tournament was the Challenge Cup, a competition between clubs in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[10] The Mitropa Cup, a competition modelled after the Challenge Cup, was created in 1927, an idea of Austrian Hugo Meisl, and played between Central European clubs.[11] In 1930, the Coupe des Nations (French: Nations Cup), the first attempt to create a cup for national champion clubs of Europe, was played and organised by Swiss club Servette.[12] Held in Geneva, it brought together ten champions from across the continent. The tournament was won by Újpest of Hungary.[12] Latin European nations came together to form the Latin Cup in 1949.[13]

After receiving reports from his journalists over the highly successful Campeonato Sudamericano de Campeones of 1948, Gabriel Hanot, editor of L'Équipe, began proposing the creation of a continent-wide tournament.[14] After Stan Cullis declared Wolverhampton Wanderers "Champions of the World" following a successful run of friendlies in the 1950s, in particular a 3–2 friendly victory against Budapest Honvéd, Hanot finally managed to convince UEFA to put into practice such a tournament.[1] It was conceived in Paris in 1955 as the European Champion Clubs' Cup.[1]

1955–67: Beginnings

.png)

The first edition of the European Cup took place during the 1955–56 season.[15][16] Sixteen teams participated (some by invitation): Milan (Italy), AGF Aarhus (Denmark), Anderlecht (Belgium), Djurgården (Sweden), Gwardia Warszawa (Poland), Hibernian (Scotland), Partizan (Yugoslavia), PSV Eindhoven (Netherlands), Rapid Wien (Austria), Real Madrid (Spain), Rot-Weiss Essen (West Germany), Saarbrücken (Saar), Servette (Switzerland), Sporting CP (Portugal), Stade de Reims (France), and Vörös Lobogó (Hungary).[15][16] The first European Cup match took place on 4 September 1955, and ended in a 3–3 draw between Sporting CP and Partizan.[15][16] The first goal in European Cup history was scored by João Baptista Martins of Sporting CP.[15][16] The inaugural final took place at the Parc des Princes between Stade de Reims and Real Madrid.[15][16][17] The Spanish squad came back from behind to win 4–3 thanks to goals from Alfredo Di Stéfano and Marquitos, as well as two goals from Héctor Rial.[15][16][17]

Real Madrid successfully defended the trophy next season in their home stadium, the Santiago Bernabéu, against Fiorentina.[18][19] After a scoreless first half, Real Madrid scored twice in six minutes to defeat the Italians.[17][18][19] In 1958, Milan failed to capitalise after going ahead on the scoreline twice, only for Real Madrid to equalise.[20][21] The final, held in Heysel Stadium, went to extra time where Francisco Gento scored the game-winning goal to allow Real Madrid to retain the title for the third consecutive season.[17][20][21] In a rematch of the first final, Real Madrid faced Stade Reims at the Neckarstadion for the 1959 final, and won 2–0.[17][22][23] West German side Eintracht Frankfurt became the first non-Latin team to reach the European Cup final.[24][25] The 1960 final holds the record for the most goals scored, with Real Madrid beating Eintracht Frankfurt 7–3 in Hampden Park, courtesy of four goals by Ferenc Puskás and a hat-trick by Alfredo Di Stéfano.[17][24][25] This was Real Madrid's fifth consecutive title, a record that still stands today.[9]

Real Madrid's reign ended in the 1960–61 season when bitter rivals Barcelona dethroned them in the first round.[26][27] Barcelona themselves, however, would be defeated in the final by Portuguese side Benfica 3–2 at Wankdorf Stadium.[26][27][28] Reinforced by Eusébio, Benfica defeated Real Madrid 5–3 at the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam and kept the title for a second consecutive season.[28][29][30] Benfica wanted to repeat Real Madrid's successful run of the 1950s after reaching the showpiece event of the 1962–63 European Cup, but a brace from Brazilian-Italian José Altafini at the Wembley Stadium gave the spoils to Milan, making the trophy leave the Iberian Peninsula for the first time ever.[31][32][33] Inter Milan beat an ageing Real Madrid 3–1 in the Ernst-Happel-Stadion to win the 1963–64 season and replicate their local-rival's success.[34][35][36] The title stayed in the city of Milan for the third year in a row after Inter beat Benfica 1–0 at their home ground, the San Siro.[37][38][39] Under the leadership of Jock Stein, Scottish club Celtic defeated Inter Milan 2–1 in the 1967 final to become the first British club to win the European Cup.[40][41] The Celtic players that day subsequently became known as the "Lisbon Lions", all of whom were born within 30 miles of Glasgow.[42]

1968-76

The 1967-68 season saw Manchester United become the first English team to win the European Cup, beating S.L. Benfica 4-1 in the final.[43] This final came 10 years after the Munich air disaster, which claimed the lives of eight United players, and injuring their Cup-winning manager, Matt Busby.[44]

Anthem

The UEFA Champions League anthem, officially titled simply as "Champions League", was written by Tony Britten, and is an adaptation of George Frideric Handel's 1727 anthem Zadok the Priest (one of his Coronation Anthems).[46][47] UEFA commissioned Britten in 1992 to arrange an anthem, and the piece was performed by London's Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and sung by the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.[46] UEFA's official website states it is, “known to set the hearts of many of the world's top footballers aflutter”.[46]

The chorus contains the three official languages used by UEFA: English, German, and French.[48] The climactic moment is set to the exclamations ‘Die Meister! Die Besten! Les Grandes Équipes! The Champions!’.[49] The anthem's chorus is played before each UEFA Champions League game as the two teams are lined up, as well as at the beginning and end of television broadcasts of the matches. In addition to the anthem, there is also entrance music, which contains parts of the anthem itself, which is played as teams enter the field.[50] The complete anthem is about three minutes long, and has two short verses and the chorus.[48]

Special vocal versions have been performed live at the Champions League Final with lyrics in other languages, changing over to the host nation's language for the chorus. These versions were performed by Andrea Bocelli (Italian) (Rome 2009, Milan 2016 and Cardiff 2017), Juan Diego Flores (Spanish) (Madrid 2010), All Angels (Wembley 2011), Jonas Kaufmann and David Garrett (Munich 2012), and Mariza (Lisbon 2014). In the 2013 final at Wembley Stadium, the chorus was played twice. In the 2018 and 2019 finals, held in Kiev and Madrid respectively, the instrumental version of the chorus was played, by 2Cellos (2018) and Asturia Girls (2019).[51][52] The anthem has been released commercially in its original version on iTunes and Spotify with the title of Champions League Theme. In 2018, composer Hans Zimmer remixed the anthem with rapper Vince Staples for EA Sports' video game FIFA 19, with it also featuring in the game's reveal trailer.[53]

Branding

In 1991, UEFA asked its commercial partner, Television Event and Media Marketing (TEAM), to help "brand" the Champions League. This resulted in the anthem, "house colours" of black and white or silver and a logo, and the "starball". The starball was created by Design Bridge, a London-based firm selected by TEAM after a competition.[54] TEAM gives particular attention to detail in how the colours and starball are depicted at matches. According to TEAM, "Irrespective of whether you are a spectator in Moscow or Milan, you will always see the same stadium dressing materials, the same opening ceremony featuring the 'starball' centre circle ceremony, and hear the same UEFA Champions League Anthem". Based on research it conducted, TEAM concluded that by 1999, "the starball logo had achieved a recognition rate of 94 percent among fans".[55]

Format

Qualification

The UEFA Champions League begins with a double round-robin group stage of 32 teams, which since the 2009–10 season is preceded by two qualification 'streams' for teams that do not receive direct entry to the tournament proper. The two streams are divided between teams qualified by virtue of being league champions, and those qualified by virtue of finishing 2nd–4th in their national championship.

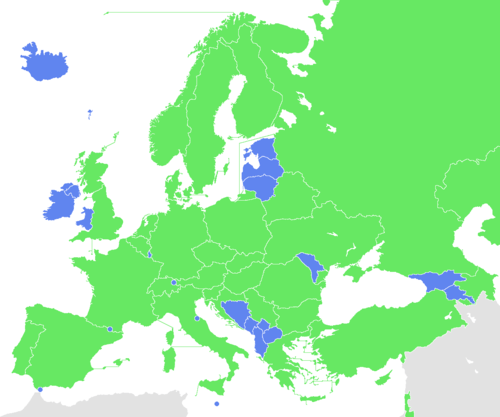

The number of teams that each association enters into the UEFA Champions League is based upon the UEFA coefficients of the member associations. These coefficients are generated by the results of clubs representing each association during the previous five Champions League and UEFA Cup/Europa League seasons. The higher an association's coefficient, the more teams represent the association in the Champions League, and the fewer qualification rounds the association's teams must compete in.

Four of the remaining six qualifying places are granted to the winners of a six-round qualifying tournament between the remaining 43 or 44 national champions, within which those champions from associations with higher coefficients receive byes to later rounds. The other two are granted to the winners of a three-round qualifying tournament between the 11 clubs from the associations ranked 5 through 15, which have qualified based upon finishing second, or third in their respective national league.

In addition to sporting criteria, any club must be licensed by its national association to participate in the Champions League. To obtain a license, the club must meet certain stadium, infrastructure, and finance requirements.

In 2005–06 season, Liverpool and Artmedia Bratislava became the first teams to reach the Champions League group stage after playing in all three qualifying rounds. In 2008–09 season, both BATE Borisov and Anorthosis Famagusta achieved the same feat. Real Madrid holds the record for the most consecutive appearances in the group stage, having qualified 22 times in a row (1997–present). They are followed by Arsenal on 19 (1998–2016)[56] and Manchester United on 18 (1996–2013).[57]

Between 1999 and 2008, no differentiation was made between champions and non-champions in qualification. The 16 top ranked teams spread across the biggest domestic leagues qualified directly for the tournament group stage. Prior to this, three preliminary knockout qualifying rounds whittled down the remaining teams, with teams starting in different rounds.

An exception to the usual European qualification system happened in 2005, after Liverpool won the Champions League the year before, but did not finish in a Champions League qualification place in the Premier League that season. UEFA gave special dispensation for Liverpool to enter the Champions League, giving England five qualifiers.[58] UEFA subsequently ruled that the defending champions qualify for the competition the following year regardless of their domestic league placing. However, for those leagues with four entrants in the Champions League, this meant that, if the Champions League winner fell outside of its domestic league's top four, it would qualify at the expense of the fourth-placed team in the league. Until 2015–16, no association could have more than four entrants in the Champions League.[59] In May 2012, Tottenham Hotspur finished fourth in the 2011–12 Premier League, two places ahead of Chelsea, but failed to qualify for the 2012–13 Champions League, after Chelsea won the 2012 final.[60] Tottenham were demoted to the 2012–13 UEFA Europa League.[60]

In May 2013,[61] it was decided that, starting from the 2015–16 season (and continuing at least for the three-year cycle until the 2017–18 season), the winners of the previous season's UEFA Europa League would qualify for the UEFA Champions League, entering at least the play-off round, and entering the group stage if the berth reserved for the Champions League title holders was not used. The previous limit of a maximum of four teams per association was increased to five, meaning that a fourth-placed team from one of the top three ranked associations would only have to be moved to the Europa League if both the Champions League and Europa League winners came from that association and both finished outside the top four of their domestic league.[62]

In 2007, Michel Platini, the UEFA president, had proposed taking one place from the three leagues with four entrants and allocating it to that nation's cup winners. This proposal was rejected in a vote at a UEFA Strategy Council meeting.[63] In the same meeting, however, it was agreed that the third-placed team in the top three leagues would receive automatic qualification for the group stage, rather than entry into the third qualifying round, while the fourth-placed team would enter the play-off round for non-champions, guaranteeing an opponent from one of the top 15 leagues in Europe. This was part of Platini's plan to increase the number of teams qualifying directly into the group stage, while simultaneously increasing the number of teams from lower-ranked nations in the group stage.[64]

In 2012, Arsène Wenger referred to qualifying for the Champion's League by finishing in the top four places in the English Premier League as the "4th Place Trophy". The phrase was coined after a pre-match conference when he was questioned about Arsenal's lack of a trophy after exiting the FA Cup. He said "The first trophy is to finish in the top four".[65] At Arsenal's 2012 AGM, Wenger was also quoted as saying: "For me there are five trophies every season: Premier League, Champions League, the third is to qualify for the Champions League..."[66]

Group stage and knockout phase

The tournament proper begins with a group stage of 32 teams, divided into eight groups of four.[67] Seeding is used whilst making the draw for this stage, whilst teams from the same nation may not be drawn into groups together. Each team plays six group stage games, meeting the other three teams in its group home and away in a round-robin format.[67] The winning team and the runners-up from each group then progress to the next round. The third-placed team enters the UEFA Europa League.

For the next stage – the last 16 – the winning team from one group plays against the runners-up from another group, and teams from the same association may not be drawn against each other. From the quarter-finals onwards, the draw is entirely random, without association protection. The tournament uses the away goals rule: if the aggregate score of the two games is tied, then the team who scored more goals at their opponent's stadium advances.[68]

The group stage is played from September to December, whilst the knock-out stage starts in February. The knock-out ties are played in a two-legged format, with the exception of the final. The final is typically held in the last two weeks of May or in the early days of June, which has happened in three consecutive odd-numbered years since 2015.

Distribution

The following is the default access list.[69]

| Teams entering in this round | Teams advancing from the previous round | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary round (4 teams) |

|

||

| First qualifying round (34 teams) |

|

| |

| Second qualifying round | Champions Path (20 teams) |

|

|

| League Path (6 teams) |

|

||

| Third qualifying round | Champions Path (12 teams) |

|

|

| League Path (8 teams) |

|

| |

| Play-off round | Champions Path (8 teams) |

|

|

| League Path (4 teams) |

| ||

| Group stage (32 teams) |

|

| |

| Knockout phase (16 teams) |

| ||

Changes will be made to the access list above if the Champions League and/or Europa League title holders qualify for the tournament via their domestic leagues.

- If the Champions League title holders qualify for the group stage via their domestic league, the champions of association 11 (Austria in 2019/2020) will enter the group stage, and champions of the highest-ranked associations in earlier rounds will also be promoted accordingly.

- If the Europa League title holders qualify for the group stage via their domestic league, the third-placed team of association 5 (France) will enter the group stage, and runners-up of the highest-ranked associations in the second qualifying round will also be promoted accordingly.

- If the Champions League and/or Europa League title holders qualify for the qualifying rounds via their domestic league, their spot in the qualifying rounds is vacated, and teams of the highest-ranked associations in earlier rounds will be promoted accordingly.

- An association may have a maximum of five teams in the Champions League.[69] Therefore, if both the Champions League and Europa League title holders come from the same top-four association and finish outside of the top four of their domestic league, the fourth-placed team of the league will not compete in the Champions League and will instead compete in the Europa League.

Referees

Ranking

The UEFA Refereeing Unit is broken down into five experience-based categories. A referee is initially placed into Category 4 with the exception of referees from France, Germany, England, Italy, or Spain. Referees from these five countries are typically comfortable with top professional matches and are therefore directly placed into Category 3. Each referee's performance is observed and evaluated after every match; his category may be revised twice per season, but a referee cannot be promoted directly from Category 3 to the Elite Category.[70]

Appointment

In co-operation with the UEFA Refereeing Unit, the UEFA Referee Committee is responsible for appointing referees to matches. Referees are appointed based on previous matches, marks, performances, and fitness levels. To discourage bias, the Champions League takes nationality into account. No referee may be of the same origins as any club in his or her respecting groups. Referee appointments, suggested by the UEFA Refereeing Unit, are sent to the UEFA Referee Committee to be discussed or revised. After a consensus is made, the name of the appointed referee remains confidential up to two days before the match for the purpose of minimising public influence.[70]

Limitations

Since 1990, a UEFA international referee cannot exceed the age of 45 years. After turning 45, a referee must step down at the end of his season. The age limit was established to ensure an elite level of fitness. Today, UEFA Champions League referees are required to pass a fitness test to even be considered at the international level.[70]

Prizes

Trophy and medals

Each year, the winning team is presented with the European Champion Clubs' Cup, the current version of which has been awarded since 1967. From the 1968–69 season and prior to the 2008–09 season any team that won the Champions League three years in a row or five times overall was awarded the official trophy permanently.[71] Each time a club achieved this a new official trophy had to be forged for the following season.[72] Five clubs own a version of the official trophy, Real Madrid, Ajax, Bayern Munich, Milan and Liverpool.[71] Since 2008, the official trophy has remained with UEFA and the clubs are awarded a replica.[71]

The current trophy is 74 cm (29 in) tall and made of silver, weighing 11 kg (24 lb). It was designed by Jörg Stadelmann, a jeweller from Bern, Switzerland, after the original was given to Real Madrid in 1966 in recognition of their six titles to date, and cost 10,000 Swiss francs.

As of the 2012–13 season, 40 gold medals are presented to the Champions League winners, and 40 silver medals to the runners-up.[73]

Prize money

As of 2019–20, the fixed amount of prize money paid to the clubs is as follows:[74]

- Preliminary qualifying round: €230,000

- First qualifying round: €280,000

- Second qualifying round: €380,000

- Third qualifying round: €480,000 (Only for clubs eliminated from the champions path, since clubs eliminated from the league path qualify directly for the UEFA Europa League group stage and therefore benefit from its distribution system.)

- Base fee for group stage: €15,250,000

- Group match victory: €2,700,000

- Group match draw: €900,000

- Round of 16: €9,500,000

- Quarter-finals: €10,500,000

- Semi-finals: €12,000,000

- Losing finalist: €15,000,000

- Winning the Final: €19,000,000

This means that, at best, a club can earn €82,450,000 of prize money under this structure, not counting shares of the qualifying rounds, play-off round or the market pool.

A large part of the distributed revenue from the UEFA Champions League is linked to the "market pool", the distribution of which is determined by the value of the television market in each nation. For the 2014–15 season, Juventus, who were the runners-up, earned nearly €89.1 million in total, of which €30.9 million was prize money, compared with the €61.0 million earned by Barcelona, who won the tournament and were awarded €36.4 million in prize money.[75]

Sponsorship

Like the FIFA World Cup, the UEFA Champions League is sponsored by a group of multinational corporations, in contrast to the single main sponsor typically found in national top-flight leagues. When the Champions League was created in 1992, it was decided that a maximum of eight companies should be allowed to sponsor the event, with each corporation being allocated four advertising boards around the perimeter of the pitch, as well as logo placement at pre- and post-match interviews and a certain number of tickets to each match. This, combined with a deal to ensure tournament sponsors were given priority on television advertisements during matches, ensured that each of the tournament's main sponsors was given maximum exposure.[76]

From the 2012–13 knockout phase, UEFA used LED advertising hoardings installed in knock-out participant stadiums, including the final stage. From the 2015–16 season onwards, UEFA has used such hoardings from the play-off round until the final.[77]

The tournament's current main sponsors are:[78]

- Expedia Group — Expedia or Hotels.com[79]

- Gazprom[80]

- Heineken[81]

- Mastercard[82]

- Nissan[83]

- PepsiCo — Lay's/Walkers, Pepsi Max and Pepsi[84]

- Santander[85]

- Sony — PlayStation 4[86]

Adidas is a secondary sponsor and supplies the official match ball, the Adidas Finale, and Macron supplies the referee uniform.[87] Hublot is also a secondary sponsor as the official fourth official board of the competition.[88]

Panini was a partner of the UEFA Champions League until 2015 when Topps signed a deal to produce stickers, trading cards and digital collections for the competition.[89]

Individual clubs may wear jerseys with advertising. However, only one sponsorship is permitted per jersey in addition to that of the kit manufacturer. Exceptions are made for non-profit organisations, which can feature on the front of the shirt, incorporated with the main sponsor or in place of it; or on the back, either below the squad number or on the collar area.[90]

If clubs play a match in a nation where the relevant sponsorship category is restricted (such as France's alcohol advertising restriction), then they must remove that logo from their jerseys. For example, when Rangers played French sides Auxerre and Strasbourg in the 1996–97 Champions League and the UEFA Cup, respectively, Rangers players wore the logo of Center Parcs instead of McEwan's Lager (both companies at the time were subsidiaries of Scottish & Newcastle).[91]

Media coverage

The competition attracts an extensive television audience, not just in Europe, but throughout the world. The final of the tournament has been, in recent years, the most-watched annual sporting event in the world.[92] The final of the 2012–13 tournament had the competition's highest TV ratings to date, drawing approximately 360 million television viewers.[93]

Records and statistics

Performances by club

Performances by nation

| Nation | Titles | Runners-up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 11 | 29 | |

| 13 | 9 | 22 | |

| 12 | 16 | 28 | |

| 7 | 10 | 17 | |

| 6 | 2 | 8 | |

| 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Totals | 64 | 64 | 128 |

- Notes

- A ^ Includes clubs representing West Germany. No clubs representing East Germany appeared in a final.

- B ^ Includes clubs representing the Former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945 to its breakup in 1992).

All-time top scorers

- As of 26 February 2020[94]

The table below does not include goals scored in the qualification stage.

| Rank | Player | Goals | Apps | Ratio | Years | Club(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 128 | 169 | 0.76 | 2003– | Manchester United (15), Real Madrid (105), Juventus (8) | |

| 2 | 114 | 141 | 0.81 | 2005– | Barcelona | |

| 3 | 71 | 142 | 0.5 | 1995–2011 | Real Madrid (66), Schalke 04 (5) | |

| 4 | 64 | 86 | 0.74 | 2011– | Borussia Dortmund (17), Bayern Munich (47) | |

| 64 | 119 | 0.54 | 2006– | Lyon (12), Real Madrid (52) | ||

| 6 | 56 | 73 | 0.77 | 1998–2009 | PSV Eindhoven (8), Manchester United (35), Real Madrid (13) | |

| 7 | 50 | 112 | 0.45 | 1997–2012 | Monaco (7), Arsenal (35), Barcelona (8) | |

| 8 | 49 | 58 | 0.84 | 1955–1964 | Real Madrid | |

| 9 | 48 | 100 | 0.48 | 1994–2012 | Dynamo Kyiv (15), Milan (29), Chelsea (4) | |

| 48 | 120 | 0.4 | 2001–2017 | Ajax (6), Juventus (3), Inter Milan (6), Barcelona (4), Milan (9), Paris Saint-Germain (20) |

Most appearances

- As of 26 February 2020[95]

The table below does not include appearances made in the qualification stage.

| Rank | Player | Apps | Years | Club(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177 | 1999–2019 | Real Madrid (150), Porto (27) | |

| 2 | 169 | 2003– | Manchester United (52), Real Madrid (101), Juventus (16) | |

| 3 | 151 | 1998–2015 | Barcelona | |

| 4 | 142 | 1995–2011 | Real Madrid (130), Schalke 04 (12) | |

| 5 | 141 | 1994–2014 | Manchester United | |

| 2005– | Barcelona | |||

| 7 | 130 | 2002–2018 | Barcelona | |

| 8 | 125 | 1994–2012 | Ajax (11), Real Madrid (25), Milan (89) | |

| 9 | 124 | 1994–2013 | Manchester United | |

| 2005– | Real Madrid |

See also

References

- "Football's premier club competition". UEFA. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Clubs". UEFA. 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "UEFA Europa League further strengthened for 2015–18 cycle" (Press release). UEFA. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- "UEFA Executive Committee approves new club competition". UEFA (Press release). 2 December 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Matches". Union of European Football Associations. 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Club competition winners do battle". UEFA. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "FIFA Club World Cup". FIFA. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- "UEFA Club Finals postponed | Inside UEFA" (Press release). UEFA. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "European Champions' Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- García, Javier; Kutschera, Ambrosius; Schöggl, Hans; Stokkermans, Karel (2009). "Austria/Habsburg Monarchy – Challenge Cup 1897–1911". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Stokkermans, Karel (2009). "Mitropa Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- Ceulemans, Bart; Michiel, Zandbelt (2009). "Coupe des Nations 1930". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Stokkermans, Karel; Gorgazzi, Osvaldo José (2006). "Latin Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- "Primeira Libertadores – História (Globo Esporte 09/02/20.l.08)". Youtube.com. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- "1955/56 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "European Champions' Cup 1955–56 – Details". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Trofeos de Fútbol". Real Madrid. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1956/57 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1956–57". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1957/58 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1957–58". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1958/59 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1958–59". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1959/60 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1959–60". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1960/61 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1960–61". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Anos 60: A "década de ouro"". Sport Lisboa e Benfica. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1961/62 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1961–62". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1962/63 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1962–63". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Coppa Campioni 1962/63". Associazione Calcio Milan. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1963/64 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1963–64". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Palmares: Prima coppa dei campioni – 1963/64" (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "1964/65 European Champions Clubs' Cup". Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Champions' Cup 1964–65". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Palmares: Prima coppa dei campioni – 1964/65" (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "A Sporting Nation – Celtic win European Cup 1967". BBC Scotland. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- "Celtic immersed in history before UEFA Cup final". Sports Illustrated. 20 May 2003. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Lennox, Doug (2009). Now You Know Soccer. Dundurn Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-55488-416-2.

now you know soccer who were the lisbon lions.

- UEFA.com. "Man. United-Benfica 1967 History | UEFA Champions League". UEFA.com. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- UEFA.com. "Season 1967 | UEFA Champions League". UEFA.com. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "The story of the UEFA Champions League anthem". YouTube. UEFA. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "UEFA Champions League anthem". UEFA. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Media, democracy and European culture. Intellect Books. 2009. p. 129. ISBN 9781841502472. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "What is the Champions League music? The lyrics and history of one of football's most famous songs". Wales Online. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Fornäs, Johan (2012). Signifying Europe (PDF). Bristol, England: intellect. pp. 185–187.

- "UEFA Champions League entrance music". YouTube. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "2Cellos to perform UEFA Champions League anthem in Kyiv". UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Asturia Girls to perform UEFA Champions League anthem in Madrid". UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- "Behind the Music: Champions League Anthem Remix with Hans Zimmer". Electronic Arts. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- King, Anthony. (2004). The new symbols of European football. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 39(3). London, Thousand Oaks, CA, New Delhi.

- TEAM. (1999). UEFA Champions League: Season Review 1998/9. Lucerne: TEAM.

- "The official website for European football – UEFA.com" (PDF). Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "EuroFutbal – Manchester United".

- "Liverpool get in Champions League". BBC Sport. BBC. 10 June 2005. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- "EXCO approves new coefficient system". UEFA. 20 May 2008. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- "Harry Redknapp and Spurs given bitter pill of Europa League by Chelsea". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. 20 May 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Added bonus for UEFA Europa League winners". UEFA.org. Union of European Football Associations. 24 May 2013.

- "UEFA Access List 2015/18 with explanations" (PDF). Bert Kassies.

- Bond, David (13 November 2007). "Clubs force UEFA's Michel Platini into climbdown". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- "Platini's Euro Cup plan rejected". BBC Sport. BBC. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- "Arsène Wenger says Champions League place is a 'trophy'". Guardian. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- "Arsenal's Trophy Cabinet". Talk Sport. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- "Champions League explained". PremierLeague.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Regulations of the UEFA Champions League 2011/12, pg 10:". UEFA.com.

- "Champions League and Europa League changes next season". UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "UEFA Referee". Uefa.com. 7 July 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "How UEFA honours multiple European Cup winners". uefa.com. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Regulations of the UEFA Champions League (PDF) from UEFA website; Page 4, §2.01 "Cup"

- "2012/13 Season" (PDF). Regulations of the UEFA Champions League: 2012–15 Cycle. UEFA. p. 8. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- UEFA.com. "2019/20 UEFA club competitions revenue distribution system". UEFA.com. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- "Clubs benefit from Champions League revenue" (PDF). Uefadirect. Union of European Football Associations (1): 1. October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- Thompson, Craig; Magnus, Ems (February 2003). "The Uefa Champions League Marketing" (PDF). Fiba Assist Magazine: 49–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- "Regulations of the UEFA Champions League 2015–18 Cycle – 2015/2016 Season – Article 66 – Other Requirements" (PDF). UEFA.org. UEFA. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "UEFA Champions League - UEFA.com". UEFA.com. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- "Uefa Champions League checks in with Expedia". SportsPro. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- “Gazprom renews UEFA Champions League partnership”. UEFA. Retrieved 18 August 2018

- "HEINEKEN extends UEFA club competition sponsorship". UEFA.com. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Carp, Sam. "Uefa cashes in Mastercard renewal". SportsPro. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "Nissan renews UEFA Champions League Partnership". UEFA.com. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "PepsiCo renews UEFA Champions League Partnership". UEFA.com. UEFA. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "Banco Santander to become UEFA Champions League Partner". UEFA.com. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "PlayStation® extends UEFA Champions League Partnership". UEFA.com. UEFA. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "adidas extends European club football partnership". UEFA.org. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "Hublot to partner Champions League and Europa League". UEFA.com.

- "Topps join UEFA licensing programme". UEFA.com. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "UEFA Kit Regulations Edition 2012" (PDF). UEFA. pp. 37, 38. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Devlin, John (3 July 2009). "An alternative to alcohol". truecoloursfootballkits.com. True Colours. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

Rangers have actually sported the Center Parcs logo during the course of two seasons.

- "Champions League final tops Super Bowl for TV market". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- Chishti, Faisal (30 May 2013). "Champions League final at Wembley drew TV audience of 360 million". Sportskeeda. Absolute Sports Private Limited. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- "UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook 2018/19" (PDF). Union of European Football Associations. pp. 5–7. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook 2018/19" (PDF). UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations (UEFA). pp. 4, 7. Retrieved 3 October 2018.