Ghilji

The Ghiljī (Pashto: غلجي, pronounced [ɣəlˈd͡ʒi]1) also spelled Ghilzai or Ghilzay (غلزی), are one of the largest tribes of Pashtuns. Their traditional homeland stretches from Ghazni and Qalati Ghilji in Afghanistan eastwards into parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan in Pakistan.[1] They are also settled in other parts of Afghanistan. The Ghilji are descended from the medieval Khalaj tribe, who are usually referred to as Turks but considered by some scholars to be remnants of the ancient Hephthalite confederacy.[2][3] The nomadic Kochi people mostly belong to the Ghilji tribe.[4]

غلجي | |

|---|---|

Ghilji chieftains in Kabul (c. 1880) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Afghanistan, Pakistan | |

| Languages | |

| Pashto | |

| Religion | |

| |

The Ghilji mostly speak the central dialect of Pashto with transitional features between the southern and northern varieties.

Etymology

According to historian C.E. Bosworth, the tribal name "Ghilji" is derived from the name of the Khalaj (خلج) tribe.[2] According to historian V. Minorsky, the ancient Turkic form of the name was Qalaj (or Qalach), but the Turkic /q/ changed to /kh/ in Arabic sources (Qalaj > Khalaj). Minorsky added: "Qalaj could have a parallel form *Ghalaj."[5] The word finally yielded Ghəljī and Ghəlzay in Pashto.

According to a popular folk etymology, the name Ghəljī or Ghəlzay is derived from Gharzay (غرزی; ghar means "mountain" while -zay means "descendant of"), a Pashto name meaning "born of mountain" or "hill people."[6]

Descent and origin

Ghiljis are descended from the Khalaj people, who are usually referred to as Turks.[5][7][8] However, some historians, including 20th-century Josef Markwart and 10th-century al-Khwarizmi, consider the Khalaj to be remnants of the Hephthalite confederacy, therefore originally Iranians,[9][10] while according to historian V. Minorsky, the Khalaj were "perhaps only politically associated with the Hephthalites."[2][11][12][13][5] The Khalaj were sometimes mentioned alongside Pashtun tribes in the armies of several local dynasties, including the Ghaznavids (977–1186).[11] Many of the Khalaj of the Ghazni and Qalati Ghilji region became assimilated into the local Pashto-speaking population.[2] They intermarried with the local Pashtuns and adopted their manners, culture, customs, and practices, also bringing their customs and culture to India where they established the Khalji dynasty of Bengal (1204–1227) and the Khalji dynasty of Delhi (1290–1320).[14] Minorsky noted: "In fact, there is absolutely nothing astonishing in a tribe of nomad habits changing its language. This happened with the Mongols settled among Turks and probably with some Turks living among Kurds."[5]

Because of their language shift and Pashtunization, the Khalaj were considered to be Pashtuns (Afghans) by the Turkic nobles of the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526).[15][16][17]

Mythical genealogy

The 17th-century Mughal courtier Nimat Allah al-Harawi, in his book Tārīkh-i Khān Jahānī wa Makhzan-i Afghānī, wrote a mythical genealogy according to which the Ghilji descended from Shah Hussain Ghori and his first wife Bībī Matō, who was a daughter of Pashtun Sufi saint Bēṭ Nīkə (progenitor of the Bettani tribal confederacy), son of Qais Abdur Rashid (progenitor of all Pashtuns).[18] Shah Hussain Ghori was described in the book as a patriarch from Ghor who was related to the Shansabani family, which later founded the Ghurid dynasty. He fled Ghor when al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf (Umayyad governor of Iraq, 694–714) dispatched an army to attack Ghor and entered into the service of Bēṭ Nīkə, who made him an adopted son. The book further stated that Shah Hussain Ghori fell in love with the saint's daughter Bībī Matō, fathering a son with her out of wedlock. The child was named by the saint as ghal-zōy (غلزوی), Pashto for "thief's son," from whom the Ghilzai derived their name. The 1595 Mughal account Ain-i-Akbari, written by Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, also gave a similar account about Ghiljis' origin. However, it named the patriarch from Ghor as "Mast Ali Ghori" (which, according to Nimat Allah al-Harawi, was the pseudonym of Shah Hussain Ghori), and asserted that the Pashtuns called him "Mati". After the illicit intercourse with one of the daughters of Bēṭ Nīkə, "when the results of this clandestine intimacy were about to become manifest, he preserved her reputation by marriage, and three sons were born to him, vis., Ghilzai (progenitor of the Ghilji tribe), Lōdī (progenitor of the Lodi tribe), and Sarwānī (progenitor of the Sarwani tribe)."[19]

Modern scholars reject these accounts as apocryphal but assert that they point to a broader contribution of Ghoris to the ethnogenesis of Pashtuns.[11]

History

The Khalaj in medieval Islamic period

Medieval Muslim scholars, including 9th-10th century geographers Ibn Khordadbeh and Istakhri, narrated that the Khalaj were one of the earliest tribes to have crossed the Amu Darya from Central Asia and settled in parts of present-day Afghanistan, especially in the Ghazni, Qalati Ghilji (also known as Qalati Khalji), and Zabulistan regions. Mid-10th-century book Hudud al-'Alam described the Khalaj as sheep-grazing nomads in Ghazni and the surrounding districts, who had a habit of wandering through seasonal pastures.

11th-century book Tarikh Yamini, written by al-Utbi, stated that when the Ghaznavid Emir Sabuktigin defeated the Hindu Shahi ruler Jayapala in 988, the Pashtuns (Afghans) and Khalaj between Laghman and Peshawar, the territory he conquered, surrendered and agreed to serve him. Al-Utbi further stated that Pashtun and Khalaj tribesmen were recruited in significant numbers by the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (999–1030) to take part in his military conquests, including his expedition to Tokharistan.[20] The Khalaj later revolted against Mahmud's son Sultan Mas'ud I of Ghazni (1030–1040), who sent a punitive expedition to obtain their submission. In 1197, Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Khalaj general from Garmsir, Helmand in the army of the Ghurid Sultan Muhammad of Ghor, captured Bihar in India, and then became the ruler of Bengal, beginning the Khalji dynasty of Bengal (1204-1227). During the time of the Mongol invasion of Khwarezmia, many Khalaj and Turkmens gathered in Peshawar and joined the army of Saif al-Din Ighraq, who was likely a Khalaj himself. This army defeated the petty king of Ghazni, Radhi al-Mulk. The last Khwarazmian ruler, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, was forced by the Mongols to flee towards the Hindu Kush. Ighraq's army, as well as many other Khalaj and other tribesmen, joined the Khwarazmian force of Jalal ad-Din and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Mongols at the 1221 Battle of Parwan. However, after the victory, the Khalaj, Turkmens, and Ghoris in the army quarreled with the Khwarazmians over the booty, and finally left, soon after which Jalal ad-Din was defeated by Genghis Khan at the Battle of the Indus and forced to flee to India. Ighraq returned to Peshawar, but later Mongol detachments defeated the 20,000–30,000 strong Khalaj, Turkmen, and Ghori tribesmen who had abandoned Jalal ad-Din. Some of these tribesmen escaped to Multan and were recruited into the army of the Delhi Sultanate.[21] Jalal-ud-din Khalji (1290-1296), who belonged to the Khalaj tribe from Qalati Khalji, founded the Khalji dynasty, which replaced the Mamluks and became the second dynasty to rule the Delhi Sultanate. 13th-century Tarikh-i Jahangushay, written by historian Ata-Malik Juvayni, narrated that a levy comprising the "Khalaj of Ghazni" and the "Afghan" (Pashtuns) were mobilized by the Mongols to take part in a punitive expedition sent to Merv in present-day Turkmenistan.[5]

Transformation of the Khalaj

Just before the Mongol invasion, Najib Bakran's geography Jahān Nāma (c. 1200-1220) described the transformation that the Khalaj tribe was going through:

The Khalaj are a tribe of Turks who from the Khallukh limits migrated to Zabulistan. Among the districts of Ghazni there is a steppe where they reside. Then, on account of the heat of the air, their complexion has changed and tended towards blackness; the tongue too has undergone alterations and become a different language.

— Najib Bakran, Jahān Nāma

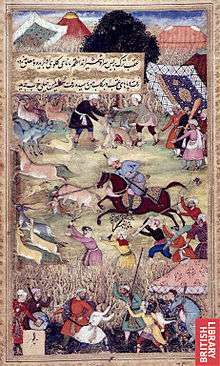

Timurid raids

One year after the 1506 Battle of Qalati Ghilji, the Timurid ruler Babur marched out of Kabul with the intention to crush Ghilji Pashtuns. On the way, the Timurid army overran Mohmand Pashtuns in Sardeh Band, and then attacked and killed Ghilji Pashtuns in the mountains of Khwaja Ismail, setting up "a pillar of Afghan heads," as Babur wrote in his Baburnama.

Many sheep were also captured during the attack. After a hunt on the plains of Katawaz the next day, where deer and wild asses were plentiful, Babur marched off to Kabul.[22][23]

Hotak dynasty

In April 1709, Mirwais Hotak, who was a member of the Hotak tribe of Ghiljis, led a successful revolution against the Safavids and founded the Hotak dynasty based in Kandahar, declaring southern Afghanistan independent of Safavid rule. His son Mahmud Hotak conquered Iran in 1722, and the Iranian city of Isfahan remained the dynasty's capital for six years.[24][25]

The dynasty ended in 1738 when its last ruler, Hussain Hotak, was defeated by Nader Shah Afshar at the Battle of Kandahar.

Azad Khan Afghan

Azad Khan Afghan, who played a prominent role in the power struggle in western Iran after the death of Nader Shah Afshar in 1747, belonged to the Andar tribe of Ghiljis. Through a series of alliance with local Kurdish and Turkish chieftains, and a policy of compromise with the Georgian ruler Erekle II—whose daughter he married—Azad rose to power between 1752 and 1757, controlling part of the Azerbaijan region up to Urmia city, northwestern and northern Persia, and parts of southwestern Turkmenistan and eastern Kurdistan.[26]

Skirmishes with British forces

.jpg)

During the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), Ghilji tribesmen played an important role in the Afghan victory against the British East India Company. On 6 January 1842, as the British Indian garrison retreated from Kabul, consisting of about 16,000 soldiers, supporting personnel, and women, a Ghilji force attacked them through the winter snows of the Hindu Kush and systematically killed them day by day. On 12 January, as the British regiment reached a hillock near Gandamak, their last survivors—about 45 British soldiers and 20 officers—were killed or held captive by the Ghilji force, leaving only one British survivor, surgeon William Brydon, to reach Jalalabad at the end of the retreat on 13 January.[27][28]

This battle became a resonant event in Ghiljis' oral history and tradition, which narrates that Brydon was intentionally let to escape so that he could tell his people about the bravery of the tribesmen.[29]

Barakzai period

After the Ghilji rebellion in Afghanistan in the 1880s, a large number of Ghiljis were forced to settle in northern Afghanistan by Barakzai Emir Abdur Rahman Khan.[30]

Among those who were exiled was Sher Khan Nashir, chief of the Kharoti Ghilji tribe, who would become the governor of Qataghan-Badakhshan Province in the 1930s. Launching an industrialization and economic development campaign, he founded the Spinzar Cotton Company and helped making Kunduz one of the wealthiest Afghan cities.[31][32][33] Sher Khan also implemented Qezel Qala harbour on the Panj River at the border with Tajikistan, which was later named Sher Khan Bandar in his honour.[34]

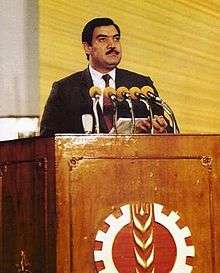

Contemporary period

.jpg)

More recently, the current Afghan president Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai (2014–present) and the former Afghan president Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai (1987–1992) belong to the Ahmadzai branch of the Ghilji tribe.

Two other former Afghan presidents, Nur Muhammad Taraki (1978–1979) and Hafizullah Amin (1979), belonged to the Tarakai and Kharoti branches of the Ghilji tribe, respectively.[35]

Areas of settlement

In Afghanistan, the Ghilji are primarily concentrated in an area which is bordered in the southeast by the Durand Line, in the northwest by a line stretching from Kandahar via Ghazni to Kabul, and in the northeast by Jalalabad. They are also found in large numbers in northern Afghanistan.[35] The Ghilji are settled in smaller numbers in parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan in Pakistan, west of the Indus River.

Before the 1947 Partition of India, the Ghilji historically used to seasonally winter as nomadic merchants in India, buying goods there, and would transport these by camel caravan in summer for sale or barter in Afghanistan.[3]

Pashto dialect

The Ghilji of the central region speak Central Pashto, a dialect with unique phonetic features, transitional between the southern and the northern dialects of Pashto.[36]

| Dialects[37] | ښ | ږ |

|---|---|---|

| Central (Ghazni) | [ç] | [ʝ] |

| Southern (Kandahar) | [ʂ] | [ʐ] |

| Northern (Kabul) | [x] | [ɡ] |

Subtribes

Notes

- ^1 In Pashto, "Ghilji" (غلجي, [ɣəlˈd͡ʒi]) is the plural form of the word. Its masculine singular is "Ghiljay" (غلجی, [ɣəlˈd͡ʒay]), while its feminine singular is "Ghiljey" (غلجۍ, [ɣəlˈd͡ʒəy]).

References

- Frye, R.N. (1999). "GHALZAY". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- "ḴALAJ i. TRIBE" - Encyclopaedia Iranica, December 15, 2010 (Pierre Oberling)

- "Ghilzay". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Khaljies are Afghan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- The Khalaj West of the Oxus, by V. Minorsky: Khyber.ORG. Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; excerpts from "The Turkish Dialect of the Khalaj", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol 10, No 2, pp 417-437 (retrieved 10 January 2007).

- Morgenstierne, G. (1999). "AFGHĀN". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Sunil Kumar (1994). "When Slaves were Nobles: The Shamsi Bandagan in the Early Delhi Sultanate". Studies in History. 10 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1177/025764309401000102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

-

- Denis Sinor (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243049. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

"The relative abundance of data norwithstanding, we have but a very fragmentary picture of Hephthalite civilization.There is no consensus con- cerning the Hephthalite language, though most scholars seem to think that it was Iranian.The Pei shih at least clearly states that the language of the Hephthalites differs from those of the High Chariots, of the Juan-juan and of the "various Hu a rather vague term which, in this context, probably refers to some Iranian peoples... According to the Liang shu the Hephthalites worshiped Heaven and also fire a clear reference to Zoroastrianism."

- University of Indiana (1954). "Asia Major, volume 4, part 1". Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

"Concerning the Hephthalites, Enoki Kazuo stresses that their place of origin was to the north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and that they were of Iranian stock he rejects the view that they were of Altaic origin, with Turkish connections."

- Robert L. Canfield (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press P. 272.pp.49. ISBN 9780521522915. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

"One cannot go into details here about that dark period of Central Asian history from the time of the Kushans down the coming of the Arabs, but one may suggest that the beginning of this period saw the last waves of Iranian-speaking nomads moving to the south, to be replaced by the Turkic-speaking nomads beginning in the late fourth century.... but our information about them, known in Classical and Islamic sources as the Chionites and Hephthalites, is so meager that much confusion has reigned regarding their origins and nature.Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation ofChionites and then Hephthalites spoke an Iranian language.In this case, as normal, the nomads adopted the written language, institutions, and culture of the settled folk.To call them "Iranian Huns" as Gobl has done is not infelicitous, for surely the bulk of the population ruled by the Chionites and Hephthalites was lranian (Gobl 1967:ix). But this was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages and the millennium-old division between settled Tajik and nomadic Turk would obtain."

- Denis Sinor (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243049. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- M. A. Shaban, "Khurasan at the Time of the Arab Conquest", in Iran and Islam, in memory of Vlademir Minorsky, Edinburgh University Press, (1971), p481; ISBN 0-85224-200-X.

- The Pearl of Pearls: The Abdālī-Durrānī Confederacy and Its Transformation under Aḥmad Shāh, Durr-i Durrān by Sajjad Nejatie. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/80750.

- Minorsky, V. "The Turkish Dialect of the Khalaj." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 10, no. 2 (1940): 417–37.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1540-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall Cavendish (2006). World and Its Peoples: The Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. p. 320. ISBN 0-7614-7571-0:"The members of the new dynasty, although they were also Turkic, had settled in Afghanistan and brought a new set of customs and culture to Delhi."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1966). The History of India, 1000 A.D.-1707 A.D. (Second ed.). Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 98. OCLC 575452554:"His ancestors, after having migrated from Turkistan, had lived for over 200 years in the Helmand valley and Lamghan, parts of Afghanistan called Garmasir or the hot region, and had adopted Afghan manners and customs. They were, therefore, wrongly looked upon as Afghans by the Turkish nobles in India as they had intermarried with local Afghans and adopted their customs and manners. They were looked down as non Turks by Turks."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abraham Eraly (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. p. 126. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8:"The prejudice of Turks was however misplaced in this case, for Khaljis were actually ethnic Turks. But they had settled in Afghanistan long before the Turkish rule was established there, and had over the centuries adopted Afghan customs and practices, intermarried with the local people, and were therefore looked down on as non-Turks by pure-bred Turks."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic. p. 28. ISBN 81-269-0123-3:"The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, had adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court. They were regarded as barbarians. The Turkish nobles had opposed the ascent of Jalal-ud-din to the throne of Delhi."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dorn, B 1836, The history of Afghans, Oriental, page.49

- Abū al-Fażl ʿAllāmī. Āʾīn-i Akbarī. Edited by Heinrich Blochmann. 2 vols. in 1. Calcutta, 1867–77.

- R. Khanam, Encyclopaedic ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia: P-Z, Volume 3 - Page 18

- Chormaqan Noyan: The First Mongol Military Governor in the Middle East by Timothy May

- Verma, Som Prakash (2016). The Illustrated Baburnama (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 1317338634.

- Beveridge, Annette Susannah (7 January 2014). The Bābur-nāma in English, Memoirs of Bābur. Project Gutenberg.

- Malleson, George Bruce (1878). History of Afghanistan, from the Earliest Period to the Outbreak of the War of 1878. London: Elibron.com. p. 227. ISBN 1402172788. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Ewans, Martin (2002). Afghanistan : a short history of its people and politics (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-050507-9.

- Perry, J. R. (1987), "Āzād Khan Afḡān", in: Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2, pp. 173-174. Online (Accessed February 20, 2012).

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012, pages 385.

- "Article in theaustralian.news.com". Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- Title The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers Peter Tomsen, PublicAffairs, 2011

- Wörmer, Nils (2012). "The Networks of Kunduz: A History of Conflict and Their Actors, from 1992 to 2001" (PDF). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. Afghanistan Analysts Network. p. 8

- Grötzbach, Erwin: Afghanistan, eine geographische Landeskunde, Darmstadt 1990, p. 263

- Emadi, Hafizullah: Dynamics of Political Development in Afghanistan. The British, Russian, and American Invasions, p. 60, at Google Books

- Tanwir, Halim: AFGHANISTAN: History, Diplomacy and Journalism Volume 1, p. 253, at Google Books

- "ḠILZĪ" - Encyclopaedia Iranica, December 15, 2001 (M. Jamil Hanifi)

- Coyle, Dennis Walter (August 2014). "Placing Wardak among Pashto varieties" (PDF). University of North Dakota:UND. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Hallberg, Daniel G. 1992. Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan, 4.