Foreign relations of the Ottoman Empire

The foreign relations of the Ottoman Empire were characterized by competition with the Persian Empire to the east and Europe to the west. The control over European minorities began to collapse in the 19th century, leading to the loss of nearly all European territory. Greece was the first to break free. By the early 20th century Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bulgarian Declaration of Independence soon followed. The Ottoman Empire allied itself with Germany in the First World War, and lost. The British successfully mobilized Arab nationalism. The Ottoman Empire thereby lost its Arab possessions, and itself soon collapsed in the early 1920s. For the period after 1923 see Foreign relations of Turkey.

Structure

The Ottoman Empire's diplomatic structure was unconventional and departed in many ways from its European counterparts. Traditionally, foreign affairs were conducted by the Reis ül-Küttab (Chief Clerk or Secretary of State) who also had other duties. In 1836, a Foreign Ministry was created.[1]

Ambassadors

Ambassadors from the Ottoman Empire were usually appointed on a temporary and limited basis, as opposed to the resident ambassadors sent by other European nations.[2][3] The Ottomans sent 145 temporary envoys to Venice between 1384 and 1600.[4] The first resident Ottoman ambassador was not seen until Yusuf Agah Efendi was sent to London in 1793.[2][5]

Ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire began arriving shortly after the fall of Constantinople. The first was Bartelemi Marcello from Venice in 1454. The French ambassador Jean de La Forêt later arrived in 1535.[6] In 1583, the ambassadors from Venice and France would attempt unsuccessfully to block William Harborne of England from taking up residence in Istanbul. This move was repeated by Venice, France and England in trying to block Dutch ambassador Cornelius Haga in 1612.[7]

Capitulations

Capitulations were a unique practice of Muslim diplomacy that was adopted by Ottoman rulers. In legal and technical terms, they were unilateral agreements made by the Sultan to a nation's merchants. These agreements were temporary, and subject to renewal by subsequent Sultans.[8][9] The origins of the capitulations comes from Harun al Rashid and his dealings with the Frankish kingdoms, but they were also used by both his successors and by the Byzantine Empire.[9]

Europe

The Ottoman Empire was a crucial part of the European states system and actively played a role in their affairs, due in part to their coterminous periods of development.[10][11]

Towards the end of the 15th century, the Ottomans began to play a larger role in the Italian Peninsula. In 1494, both the Papacy and the Kingdom of Naples petitioned the Sultan directly for his assistance against Charles VIII of France in the First Italian War.[12]

Ottoman policy towards Europe during the 16th century was one of disruption against the Habsburg dynasties.[10] The Ottomans collaborated with Francis I of France and his Protestant allies in the 1530s while fighting the Habsburgs.[10] Although the French had sought an alliance with the Ottomans as early as 1531, one was not concluded until 1536. The sultan then gave the French freedom of trade throughout the empire, and plans were drawn up for an invasion of Italy from both the north and the south in 1537.[13]

Francis I later admitted to a Venetian ambassador that the Ottoman Empire was the only thing that prevented Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor from creating a Europe-wide empire under Habsburg dominion.[14][15]

Later, the Dutch would ally with the Ottomans. Prince William of Orange coordinated his strategic moves with those of the Ottomans during the Turkish negotiations with Philip II of Spain in the 1570s.[10] After the Habsburgs inherited the Portuguese crown in 1580, Dutch forces attacked their Portuguese trading rivals while the Turks, supportive of the Dutch bid for independence, attacked the Habsburgs in Eastern Europe.[16]

In the 19th century the Ottoman Empire grew weaker and Britain increasingly became its protector, even fighting the Crimean War in the 1850s to help it out. Three British leaders played major roles. Lord Palmerston in the 1830-65 era considered the Ottoman Empire an essential component in the balance of power, was the most favourable toward Constantinople. William Gladstone in the 1870s sought to build a Concert of Europe that would support the survival of the empire. In the 1880s and 1890s Lord Salisbury contemplated an orderly dismemberment of it, in such a way as to reduce rivalry between the greater powers.[17]

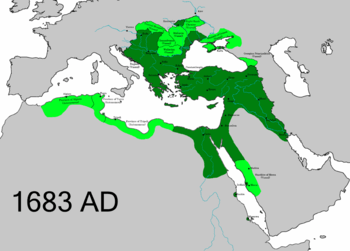

Great Turkish War: 1683–1699

The Great Turkish War or the "War of the Holy League" was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and ad-hoc European coalition the Holy League (Latin: Sacra Ligua). The coalition was organized by Pope Innocent XI and included the Papal States, the Holy Roman Empire under Habsburg Emperor Leopold I, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of John III Sobieski, and the Venetian Republic; Russia joined the League in 1686. Intensive fighting began in 1683 when Ottoman commander Kara Mustafa brought an army of 200,000 soldiers to besiege, Vienna.[18] The issue was control of Central and Eastern Europe. By September, the invaders were defeated in full retreat down the Danube. It ended with the signing of the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The war was a defeat for the Ottoman Empire, which for the first time lost large amounts of territory. It lost lands in Hungary and Poland, as well as part of the western Balkans. The war marked the first time Russia was involved in a western European alliance.[19][20]

References

- Foundations of the Ottoman Foreign Ministry International Journal of Middle East Studies, 1974

- Yurdusev et al., 2.

- Watson, 218.

- Yurdusev et al., 27.

- Yurdusev et al., 30.

- Yurdusev et al., 39.

- Yurdusev et al., 39–40.

- Yurdusev et al., 41.

- Watson, 217.

- Watson, 177.

- Yurdusev et al., 21.

- Yurdusev et al., 22.

- Inalcik, 36.

- Yurdusev et al., 23.

- Inalcik, 35.

- Watson, 222.

- David Steele, "Three British Prime Ministers and the Survival of the Ottoman Empire, 1855–1902." Middle Eastern Studies 50.1 (2014): 43-60.

- Simon Millar, Vienna 1683: Christian Europe Repels the Ottomans (Osprey, 2008)

- John Wolf, The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715 (1951), pp 15–53.

- Kenneth Meyer Setton, Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century (Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, 1991) excerpt

Sources

- Davison, Roderic H. Nineteenth century Ottoman diplomacy and reforms (Isis Press, 1999).

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman’s Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923 (New York: Basic, 2005).

- Hale, William. Turkish foreign policy since 1774 (Routledge, 2012).

- Horn, David Bayne. Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century (1967), covers 1603 to 1702; pp 352-77.

- Inalcik, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. (Praegar, 1971). ISBN 1-84212-442-0.

- Pamuk, Şevket. The Ottoman Empire and European Capitalism, 1820–1913: Trade, Investment and Production (Cambridge UP, 1987).

- Quataert, Donald. The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922 (Cambridge UP, 2000).

- Rodogno, Davide. Against Massacre: Humanitarian Interventions in the Ottoman Empire, 1815-1914 (Princeton UP, 2012).

- Watson, Adam. The evolution of international society: a comparative historical analysis. (Routledge, 1992). ISBN 0-415-06998-X.

- Yurdusev, A. Nuri et al. Ottoman Diplomacy: Conventional or Unconventional?. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). ISBN 0-333-71364-8.

Further reading

- Hitzel, Frédéric (2010). "Les ambassades occidentales à Constantinople et la diffusion d'une certaine image de l'Orient". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 154 (1): 277–292.

See also

- International relations, 1648–1814

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- British foreign policy in the Middle East

- List of diplomatic missions of the Ottoman Empire

- Foreign relations of Turkey

- Persian-Ottoman relations

- Ottoman Empire–United States relations

- State organisation of the Ottoman Empire