List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire

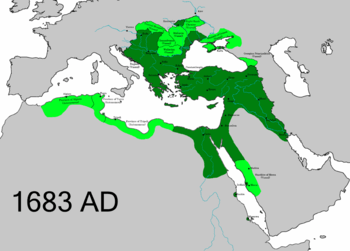

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire (Turkish: Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its height, the Ottoman Empire spanned an area from Hungary in the north to Yemen in the south, and from Algeria in the west to Iraq in the east. Administered at first from the city of Söğüt since before 1280 and then from the city of Bursa since 1323 or 1324, the empire's capital was moved to Adrianople (now known as Edirne in English) in 1363 following its conquest by Murad I, and then to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) in 1453 following its conquest by Mehmed II.[1]

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire | |

|---|---|

| Osmanlı padişahları | |

Imperial | |

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Style | His Imperial Majesty |

| First monarch | Osman I (c. 1299–1323/4) |

| Last monarch | Mehmed VI (1918–1922) |

| Formation | c. 1299 |

| Abolition | 1 November 1922 |

| Residence | Palaces in Istanbul:

|

| Appointer | Hereditary |

The Ottoman Empire's early years have been the subject of varying narratives due to the difficulty of discerning fact from legend. The empire came into existence at the end of the thirteenth century, and its first ruler (and the namesake of the Empire) was Osman I. According to later, often unreliable Ottoman tradition, Osman was a descendant of the Kayı tribe of the Oghuz Turks.[2] The eponymous Ottoman dynasty he founded endured for six centuries through the reigns of 36 sultans. The Ottoman Empire disappeared as a result of the defeat of the Central Powers with whom it had allied itself during World War I. The partitioning of the Empire by the victorious Allies and the ensuing Turkish War of Independence led to the abolition of the sultanate in 1922 and the birth of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1922.[3]

Names

The sultan was also referred to as the Padishah (Ottoman Turkish: پادشاه, romanized: pâdişâh, French: Padichah). In Ottoman usage the word "Padisha" was usually used except "sultan" was used when he was directly named.[4]

Names of the sultan in languages used by ethnic minorities:[4]

- Arabic: In some documents "Padishah" was replaced by "malik"[4]

- Armenian: "Sultann" and "PADIŠAH"

- Bulgarian: In earlier periods Bulgarian people called him the "tsar". The translation of the Ottoman Constitution of 1876 instead used direct translations of "sultan" (Sultan) and "padishah" (Padišax)[4]

- Greek: In earlier periods the Greeks used the Byzantine Empire-style name "basileus". The translation of the Ottoman Constitution of 1876 instead used a direct transliterations of "sultan" (Σουλτάνος Soultanos) and "padishah" (ΠΑΔΙΣΑΧ padisach).[4]

- Judaeo-Spanish: Especially in older documents, El Rey ("the king") was used. In addition some Ladino documents used sultan (in Hebrew chartacters: שלטנ and ולטנ).[4]

- Persian: "Padishah" (as pādešāh) was used in Persian as well.

State organisation of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire was an absolute monarchy during much of its existence. By the second half of the fifteenth century, the sultan sat at the apex of a hierarchical system and acted in political, military, judicial, social, and religious capacities under a variety of titles.[a] He was theoretically responsible only to God and God's law (the Islamic شریعت şeriat, known in Arabic as شريعة sharia), of which he was the chief executor. His heavenly mandate was reflected in Islamic titles such as "shadow of God on Earth" (ظل الله في العالم ẓıll Allāh fī'l-ʿalem) and "caliph of the face of the earth" (خلیفه روی زمین Ḫalife-i rū-yi zemīn).[5] All offices were filled by his authority, and every law was issued by him in the form of a decree called firman (فرمان). He was the supreme military commander and had the official title to all land.[6] Osman (died 1323/4) son of Ertuğrul was the first ruler of the Ottoman state, which during his reign constituted a small principality (beylik) in the region of Bithynia on the frontier of the Byzantine Empire.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, Ottoman sultans came to regard themselves as the successors of the Roman Empire, hence their occasional use of the titles caesar (قیصر qayser) of Rûm, and emperor,[5][7][8] as well as the caliph of Islam.[b] Newly enthroned Ottoman rulers were girded with the Sword of Osman, an important ceremony that served as the equivalent of European monarchs' coronation.[9] A non-girded sultan was not eligible to have his children included in the line of succession.[10]

Although absolute in theory and in principle, the sultan's powers were limited in practice. Political decisions had to take into account the opinions and attitudes of important members of the dynasty, the bureaucratic and military establishments, as well as religious leaders.[6] Beginning in the last decades of the sixteenth century, the role of the Ottoman sultans in the government of the empire began to decrease, in a period known as the Transformation of the Ottoman Empire. Despite being barred from inheriting the throne,[11] women of the imperial harem—especially the reigning sultan's mother, known as the valide sultan—also played an important behind-the-scenes political role, effectively ruling the empire during the period known as the Sultanate of Women.[12]

Constitutionalism was established during the reign Abdul Hamid II, who thus became the empire's last absolute ruler and its reluctant first constitutional monarch.[13] Although Abdul Hamid II abolished the parliament and the constitution to return to personal rule in 1878, he was again forced in 1908 to reinstall constitutionalism and was deposed. Since 2017, the head of the House of Osman has been Dündar Ali Osman, a great-grandson of Abdul Hamid II.[14]

List of sultans

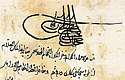

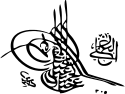

The table below lists Ottoman sultans, as well as the last Ottoman caliph, in chronological order. The tughras were the calligraphic seals or signatures used by Ottoman sultans. They were displayed on all official documents as well as on coins, and were far more important in identifying a sultan than his portrait. The "Notes" column contains information on each sultan's parentage and fate. For earlier rulers, there is usually a time gap between the moment a sultan's reign ended and the moment his successor was enthroned. This is because the Ottomans in that era practiced what historian Quataert has described as "survival of the fittest, not eldest, son": when a sultan died, his sons had to fight each other for the throne until a victor emerged. Because of the infighting and numerous fratricides that occurred, a sultan's death date therefore did not always coincide with the accession date of his successor.[15] In 1617, the law of succession changed from survival of the fittest to a system based on agnatic seniority (اکبریت ekberiyet), whereby the throne went to the oldest male of the family. This in turn explains why from the 17th century onwards a deceased sultan was rarely succeeded by his own son, but usually by an uncle or brother.[16] Agnatic seniority was retained until the abolition of the sultanate, despite unsuccessful attempts in the 19th century to replace it with primogeniture.[17]

| № | Sultan | Portrait | Reigned from | Reigned until | Tughra | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rise of the Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1453) | ||||||

| 1 | Osman I ĠĀZĪ (the Warrior) |

|

c. 1299 | c. 1326 [18] | — [c] |

|

| 2 | Orhan ĠĀZĪ (the Warrior) |

|

c. 1326 [21] | 1362 |

| |

| 3 | Murad I SULTÂN-I ÂZAM (the Most Exalted Sultan) HÜDAVENDİGÂR (the Devotee of God) ŞEHÎD (the Martyr) [23][b] |

|

1362 | 15 June 1389 |  |

|

| 4 | Bayezid I SULTÂN-I RÛM (Sultan of the Roman Empire) YILDIRIM (Thunderbolt) |

|

15 June 1389 | 20 July 1402 |

| |

| Ottoman Interregnum[d] (20 July 1402 – 5 July 1413) | ||||||

| — | İsa Çelebi The Co-Sultan of Anatolia |

|

1403–1405 (Sultan of the Western Anatolian Territory) |

1406 | — |

|

| — | Emir (Amir) Süleyman Çelebi The First Sultan of Rumelia |

|

20 July 1402 | 17 February 1411[26] |  |

|

| — | Musa Çelebi The Second Sultan of Rumelia |

|

18 February 1411 | 5 July 1413[28] | — | |

| — | Mehmed Çelebi The Sultan of Anatolia |

|

1403–1406 (Sultan of the Eastern Anatolian Territory) 1406–1413 (The Sultan of Anatolia) |

5 July 1413 | — |

|

| Sultanate resumed | ||||||

| 5 | Mehmed I ÇELEBİ (The Affable) KİRİŞÇİ (lit. The Bowstring Maker for his support) |

|

5 July 1413 | 26 May 1421 |

| |

| — | Mustafa Çelebi The Third Sultan of Rumelia |

— | January 1419 | May 1422 | — | |

| 6 | Murad II KOCA (The Great) Ghazavat-ı Sultan |

|

25 June 1421 | 1444 |

| |

| 7 | Mehmed II FĀTİḤ (The Conqueror) فاتح |

|

1444 | 1446 |

| |

| (6) | Murad II KOCA (The Great) |

|

1446 | 3 February 1451 | ||

| Growth of the Ottoman Empire (1453 – 1550) | ||||||

| (7) | Mehmed II KAYSER-İ RÛM (Caesar of the Roman Empire) FĀTİḤ (The Conqueror) فاتح |

|

3 February 1451 | 3 May 1481 |

| |

| 8 | Bayezid II VELÎ (The Saint) |

|

19 May 1481 | 25 April 1512 |

| |

| — | Sultan Cem |  |

28 May 1481 | 20 June 1481 |  |

|

| 9 | Selim I YAVUZ (The Strong) Hadim'ul Haramain'ish-Sharifain (Servant of Mecca and Medina) |

|

25 April 1512 | 21 September 1520 |

| |

| 10 | Suleiman I MUHTEŞEM (The Magnificent) or

KANÛNÎ (The Lawgiver) |

|

30 September 1520 | 6 September 1566 |  |

|

| Transformation of the Ottoman Empire (1550 – 1700) | ||||||

| 11 | Selim II SARI (The Blond) Fatih Cyprus (The Conqueror of Cyprus) Sarhoş (The Drunk) |

|

29 September 1566 | 21 December 1574 |

| |

| 12 | Murad III Dindar (The Pious) |

|

22 December 1574 | 16 January 1595 |

| |

| 13 | Mehmed III ADLÎ (The Just) |

|

16 January 1595 | 22 December 1603 |

| |

| 14 | Ahmed I BAḪTī (The Fortunate) |

|

22 December 1603 | 22 November 1617 |

| |

| 15 | Mustafa I DELİ (The Mad) |

.jpg) |

22 November 1617 | 26 February 1618 |

| |

| 16 | Osman II GENÇ (The Young) ŞEHÎD (The Martyr) شهيد |

|

26 February 1618 | 19 May 1622 |

| |

| (15) | Mustafa I DELİ (The Mad) |

.jpg) |

20 May 1622 | 10 September 1623 | ||

| 17 | Murad IV SAHİB-Î KIRAN The Conqueror of Baghdad ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) غازى |

|

10 September 1623 | 8 February 1640 |

| |

| 18 | Ibrahim DELİ (The Mad) The Conqueror of Crete ŞEHÎD |

|

9 February 1640 | 8 August 1648 |

| |

| 19 | Mehmed IV AVCI (The Hunter) ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) غازى |

.jpg) |

8 August 1648 | 8 November 1687 |

| |

| 20 | Suleiman II ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) |

|

8 November 1687 | 22 June 1691 |

| |

| 21 | Ahmed II ḪĀN ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior Prince) |

|

22 June 1691 | 6 February 1695 |

| |

| 22 | Mustafa II ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) |

|

6 February 1695 | 22 August 1703 |

| |

| Stagnation and reform of the Ottoman Empire (1700 – 1827) | ||||||

| 23 | Ahmed III Tulip Era Sultan ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) |

|

22 August 1703 | 1 October 1730 |

| |

| 24 | Mahmud I ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) KAMBUR (The Hunchback) |

|

2 October 1730 | 13 December 1754 |

| |

| 25 | Osman III SOFU (The Devout) |

|

13 December 1754 | 30 October 1757 |

| |

| 26 | Mustafa III YENİLİKÇİ (The First Innovative) |

|

30 October 1757 | 21 January 1774 |

| |

| 27 | Abdul Hamid I Abd ūl-Hāmīd (The Servant of God) ISLAHATÇI (The Improver) ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) |

|

21 January 1774 | 7 April 1789 |

| |

| 28 | Selim III BESTEKÂR (The Composer) NİZÂMÎ (Regulative - Orderly) ŞEHÎD (The Martyr) |

|

7 April 1789 | 29 May 1807 |

| |

| 29 | Mustafa IV |  |

29 May 1807 | 28 July 1808 |

| |

| Modernization of the Ottoman Empire (1827 – 1908) | ||||||

| 30 | Mahmud II İNKILÂPÇI (The Reformer) ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) |

|

28 July 1808 | 1 July 1839 |

| |

| 31 | Abdulmejid I TANZİMÂTÇI (The Strong Reformist or The Advocate of Reorganization) ĠĀZĪ (The Warrior) |

|

1 July 1839 | 25 June 1861 |

| |

| 32 | Abdulaziz BAḪTSIZ (The Unfortunate) ŞEHĪD (The Martyr) |

|

25 June 1861 | 30 May 1876 |  |

|

| 33 | Murad V |  |

30 May 1876 | 31 August 1876 |

| |

| 34 | Abdul Hamid II Ulû Sultân Abd ūl-Hāmīd Khan (The Sublime Khan) |

|

31 August 1876 | 27 April 1909 |  |

|

| 35 | Mehmed V REŞÂD (Rashād) (The True Path Follower) |

|

27 April 1909 | 3 July 1918 |  |

|

| 36 | Mehmed VI VAHDETTİN (Wāhīd ād-Dīn) (The Unifier of Dīn (Islam) or The Oneness of Islam) |

|

4 July 1918 | 1 November 1922 |  |

|

| Caliph under the Republic (1 November 1922 – 3 March 1924) | ||||||

| — | Abdulmejid II |  |

18 November 1922 | 3 March 1924 | — [c] |

|

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sultans of the Ottoman Empire. |

- Line of succession to the Ottoman throne

- Ottoman Emperors family tree

- Ottoman family tree (more detailed)

- List of Valide Sultans

- List of Ottoman Grand Viziers

- List of admirals in the Ottoman Empire

- List of Ottoman Kaptan Pashas

Notes

- a1 2 : The full style of the Ottoman ruler was complex, as it was composed of several titles and evolved over the centuries. The title of sultan was used continuously by all rulers almost from the beginning. However, because it was widespread in the Muslim world, the Ottomans quickly adopted variations of it to dissociate themselves from other Muslim rulers of lesser status. Murad I, the third Ottoman monarch, styled himself sultân-ı âzam (سلطان اعظم, the most exalted sultan) and hüdavendigar (خداوندگار, emperor), titles used by the Anatolian Seljuqs and the Mongol Ilkhanids respectively. His son Bayezid I adopted the style Sultan of Rûm, Rûm being an old Islamic name for the Roman Empire. The combining of the Islamic and Central Asian heritages of the Ottomans led to the adoption of the title that became the standard designation of the Ottoman ruler: Sultan [Name] Khan.[68] Ironically, although the title of sultan is most often associated in the Western world with the Ottomans, people within Turkey generally use the title of padishah far more frequently when referring to rulers of the Ottoman Dynasty.[69]

- b1 2 3 : The Ottoman Caliphate was one of the most important positions held by rulers of the Ottoman Dynasty. The caliphate symbolized their spiritual power, whereas the sultanate represented their temporal power. According to Ottoman historiography, Murad I adopted the title of caliph during his reign (1362 to 1389), and Selim I later strengthened the caliphal authority during his conquest of Egypt in 1516-1517. However, the general consensus among modern scholars is that Ottoman rulers had used the title of caliph before the conquest of Egypt, as early as during the reign of Murad I (1362–1389), who brought most of the Balkans under Ottoman rule and established the title of sultan in 1383. It is currently agreed that the caliphate "disappeared" for two-and-a-half centuries, before being revived with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, signed between the Ottoman Empire and Catherine II of Russia in 1774. The treaty was highly symbolic, since it marked the first international recognition of the Ottomans' claim to the caliphate. Although the treaty made official the Ottoman Empire's loss of the Crimean Khanate, it acknowledged the Ottoman caliph's continuing religious authority over Muslims in Russia.[70] From the 18th century onwards, Ottoman sultans increasingly emphasized their status as caliphs in order to stir Pan-Islamist sentiments among the empire's Muslims in the face of encroaching European imperialism. When World War I broke out, the sultan/caliph issued a call for jihad in 1914 against the Ottoman Empire's Allied enemies, unsuccessfully attempting to incite the subjects of the French, British and Russian empires to revolt. Abdul Hamid II was by far the Ottoman Sultan who made the most use of his caliphal position, and was recognized as Caliph by many Muslim heads of state, even as far away as Sumatra.[71] He had his claim to the title inserted into the 1876 Constitution (Article 4).[72]

- c1 2 : Tughras were used by 35 out of 36 Ottoman sultans, starting with Orhan in the 14th century, whose tughra has been found on two different documents. No tughra bearing the name of Osman I, the founder of the empire, has ever been discovered,[73] although a coin with the inscription "Osman bin Ertuğrul" has been identified.[19] Abdulmejid II, the last Ottoman Caliph, also lacked a tughra of his own, since he did not serve as head of state (that position being held by Mustafa Kemal, President of the newly founded Republic of Turkey) but as a religious and royal figurehead.

- d^ : The Ottoman Interregnum, also known as the Ottoman Triumvirate (Turkish: Fetret Devri), was a period of chaos in the Ottoman Empire which lasted from 1402 to 1413. It started following the defeat and capture of Bayezid I by the Turco-Mongol warlord Tamerlane at the Battle of Ankara, which was fought on 20 July 1402. Bayezid's sons fought each other for over a decade, until Mehmed I emerged as the undisputed victor in 1413.[74]

- e^ : The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire was a gradual process which started with the abolition of the sultanate and ended with that of the caliphate 16 months later. The sultanate was formally abolished on 1 November 1922. Sultan Mehmed VI fled to Malta on 17 November aboard the British warship Malaya.[64] This event marked the end of the Ottoman Dynasty, not of the Ottoman State nor of the Ottoman Caliphate. On 18 November, the Grand National Assembly (TBMM) elected Mehmed VI's cousin Abdulmejid II, the then crown prince, as caliph.[75] The official end of the Ottoman State was declared through the Treaty of Lausanne (24 July 1923), which recognized the new "Ankara government," and not the old Istanbul-based Ottoman government, as representing the rightful owner and successor state. The Republic of Turkey was proclaimed by the TBMM on 29 October 1923, with Mustafa Kemal as its first President.[76] Although Abdulmejid II was a figurehead lacking any political power, he remained in his position of Caliph until the office of the Caliphate was abolished by the TBMM on 3 March 1924.[72] Mehmed VI later tried unsuccessfully to reinstall himself as caliph in the Hejaz.[77]

Architectural work of Sultans

Architectural Contributions

Between the time of Mehmed II’s first reign in 1444 and the end of Mahmud II’s sultanate in 1839, it became tradition for Sultans and other esteemed members of the Ottoman state to build mosques, public works, and other types of architecture. Some of these works were used to commemorate individuals, while others were formed to advance the needs of the state through infrastructure such as schools, dams, or libraries[78]

Some sultanates were more active than others in producing well-known architectural works. Others, like Selim I, spent much of their time out on campaign, and had less of a focus on architectural feats. Some Sultans, such as Ahmed III, were coerced by epidemics and other societal developments into pursuing architectural improvement projects in order to serve the needs of the Empire[79].

Structural, Artistic, and Technological Development

Over the course of time, Ottoman signatures in architectural work changed, as well as the technologies employed. Some examples of this include the changes in the number and size of cupolas, the style of courtyards, the eventual introduction of free-standing libraries, and the advancement of aqua-duct and dam work.

Notable Mosques

Fatih Mosque and the Blue Mosque are among the more famous mosques constructed by Sultans. The Fatih Mosque was originally built under “The Conqueror”, Mehmed II, in the mid-1400s AD in hopes of rivaling the greatness of the Hagia Sofia[80]. This act was a significant show of power following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. Due to severe earthquakes in the region in 1766, the Fatih Mosque was damaged and had to undergo reconstruction in the early 1770s under Mustafa III’s Sultanate[81].

The Blue Mosque was constructed under Ahmed I in approximately 1603. The mosque in part gains its name from its stunning interior and exterior blue attributes, and placement near the seashore of Istanbul. To this day, the mosque dominates the sea-side view of Istanbul.

The Blue Mosque was notably constructed on the opposite hill of the Hagia Sofia, and both mosques played a part in the political developments of the Kadizadeli movement spanning much of the 17th century. While the Hagia Sofia preached towards a puritanical movement, the Blue Mosque preached the Sufi order[82]. The power of two mosques in the same relative neighborhood preaching different interpretations of muslim faith invited political, religious, and social discourse in Istanbul that at times served as a threat to the power of the Sultan[83].

An important thing to note is that while the Hagia Sofia was an influential mosque in Ottoman history, and is well-known to this day, the mosque was actually not built by the Ottomans themselves. The Hagia Sofia was converted into a mosque from a church following the capture of Constantinople in 1453, when control of the area moved from the hands of the Byzantines to the Ottomans.

Major Architectural Works of Sultanates

Below is a chart of several major architectural projects, listed by sultanate[84]:

| Sultanate | Architecture | Year | Type, Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mehmed II | Palace at Theodosian Forum | 1453 | Palace site |

| Mosque in Eyyub | 1458 | Mosque | |

| Fatih | - | Imperial complex | |

| Bezistan | - | - | |

| Eski Odalar | - | Mosque, “Old Barracks” | |

| Karaman | 1467 | Markets of the major and the minor | |

| Sarradj Khane | 1475 | Saddlers’ market | |

| Bayezid II | Dawud Pasha’s Mosque | 1485 | Mosque |

| Atik Ali Pasha’s Mosque | 1500 | Religious complex in the capital | |

| Selim I | - | - | - |

| Sulyeman | Mosque of Sultan Selim | 1522 | Mosque in memory of Suleyman’s father, Selim I |

| Topkapi Palace Renovations | - | Renovations to the Topkapi palace | |

| Ibrahim Pasha’s Palace | - | On the hippodrome | |

| Khurrem Sultane’s Complex | - | Includes a mosque, imaret, and hospital on Awret Bazari | |

| Mosque of Mehemmed | 1543 | Mosque in memory of prince Mehemmed | |

| Mihir-i Mah Sultane’s Mosque | 1548 | Mosque with a medrese and caravanserai at Uskudar | |

| Suleymaniyye | 1550 | New imperial complex built on land of the Old Palace | |

| Rustem Pasha’s Kahn | 1550 | At Ghalata | |

| Rustem’s Medrese | 1550 | Placed below Mahmud Pasha’s mosque | |

| Kara Ahmed Pasha’s Mosque | 1560 | Located near Topkapi Palace, including a medrese | |

| Mosque of Rustem Pasha | 1562 | Built on Attar Khalil | |

| Sinan Pasha’s Mosque | - | Placed at Beshiktash, including a medrese | |

| Mihir-i Mah Sultane’s Mosque | Approx 1568 | Includes a courtyard medrese at Edirne Kapi | |

| Selim II | Funeral Monument | 1568 | Placed at Eyyub, includes a mausoleum and a medrese |

| Complex by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha | 1572 | Includes a courtyard medrese and zaqiya | |

| Piyale Pasha’s Mosque | 1572 | Placed behind the Arsenal outside of Ghalata, set for prayers before departure of the fleet | |

| Mosque of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha | 1577 | Located beside the Arsenal outside of Ghalata, commemorates the Sultan’s service | |

| Murad III | Mosque of the High Admiral Kilidj Ali Pasha | 1581 | Mosque at Topkhane |

| Complex by Nur Banu Sultane | 1583 | Complex near Uskudar, with a caravanserai, zawiya, mosque, and medrese, serving as a transit depot for caravans arriving from Anatolia | |

| Contribution by Shemsi Pasha | 1581 | Located at Uskudar | |

| Mosque of Zal Mahmud Pasha | 1580 | Placed at Eyyub, includes medreses | |

| Mosque of Mesih Mehmed Pasha | 1586 | Placed at Kara Gumruk | |

| Mosque of Nishandji Mehmed Pasha | 1588 | Placed between Fatih and Edirne Kapi | |

| Djerrah Mehmed Pasha’s Mosque | 1593 | Mosque | |

| Mehmed III | Safiyye Sultane’s Mosque | 1595 - 1663* | *Mosque uncompleted until Mehemmed IV |

| Contributions by Ghandanfer Agha | 1590 | Includes medrese, mausoleum, fountain | |

| Contributions by Sinan Pasha | 1592 | Includes medrese, mausoleum, fountain | |

| Ahmed I | Ahmed I’s Imperial Complex and the Blue Mosque | 1603 | Mosque as well as a new imperial complex |

| Contributions by Kuyudju Murad Pasha | 1610 | Includes a medrese, mausoleum, and fountain | |

| Contributions by Ekmekdj-zade Ahmed Pasha | Pre-1618 | Includes a medrese, mausoleum, and fountain | |

| Kosem Sultane’s Mosque | - | Placed in Uskudar | |

| Mustafa I | - | - | - |

| Osman II | - | - | - |

| Murad IV | Contributions by Bayram Pasha | 1634 | Includes a medrese, mausoleum, fountain, and zawiya |

| Ibrahim | - | - | - |

| Mehmed IV | Contributions by Koprulu Mehmed Pasha | 1660 | - |

| Koprulu Fadil Ahmed Pasha’s First Independent Library | Pre-1676 | Free-standing library | |

| Contributions by Merzinfonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha | 1681 | Includes a medrese, mausoleum, and fountain | |

| Suleiman II | - | - | - |

| Ahmed II | Contributions by Damad Ibrahim Pasha | 1719 | Includes medrese, mausoleum, fountain |

| Mustafa II | Contributions by Amjazade Huseyin Pasha | 1700 | Includes medrese, mausoleum, fountain |

| Ahmed III | Ali Pasha’s Independent Library | 1715 | Free-standing library |

| Ahmed III’s Independent Library | 1719 | Free-standing library | |

| Monumental Fountain by Damad Ibrahim Pasha | 1728 | “Tulip Period” construction of fountains | |

| Ahmed III’s Monumental Fountain | 1729 | At the Topkapi Palace | |

| “Tulip Period” Construction | 1718 - 1730 | Construction of housing, libraries, mosques, fountains, and public works | |

| Mahmud I | Mahmud I’s Monumental Fountain | 1732 | Placed in Topkhane |

| Saliha Sultane’s Monumental Fountain | 1732 | In front of the Arsenal, of Azap Kapi | |

| Hekim-oghlu Ali Pasha’s Monumental Fountain | 1732 | Of Ka’ba Tash | |

| Complex by Hadjdji Mehmed Emin Agha | 1741 | Placed at Dolma Baghce, includes sebit, mausoleum, fountain, school | |

| Topluzu Bend Dam | 1750 | Placed on the network of Taksim, utilized improved water pressure balancing technology | |

| Osman III | Library Complex of Nur-u Othmaniyye | 1755 | - |

| Mustafa III | Library Complex of Raghib Pasha | 1762 | - |

| Aywad Bendi Dam | 1765 | - | |

| Mosque of Ayazma | 1758 | Mosque | |

| Mosque of Laleli | 1760 | Mosque | |

| Mosque of Fatih | 1766 | Mosque | |

| Abdul Hamid I | Library Complex of Murad Molla | 1775 | - |

| Mosque of Rabi a Sultane and Humashah Kadin | 1789 | Mosque | |

| Selim III | Walide Bend Dam | 1797 | - |

| Funeral Monument by Mihr Shah Sultane | 1792 | Placed in Eyyub, includes imaret, sebit, mausoleum | |

| Funeral Monument by Shah Sultane | 1800 | Placed in Eyyub, includes mausoleum, school, sebil | |

| Funeral Monument of Nakshidil Sultane | 1818 | Placed in the cemetery of Fatih | |

| Mosque Zawiya Kucuk Efendi | 1825 | Mosque | |

| Selim III’s Mosque | 1802 | Mosque | |

| Mustafa IV | - | - | - |

| Mahmud II | Pavilion of Ceremonies | 1810 | Placed in the Topkapi Palace |

| School of Djerwi Kalfa | 1819 | - | |

| Mahmud II’s Dam | 1839 | - | |

| Mahmud II’s Mausoleum | 1839 | - | |

References

- Stavrides 2001, p. 21

-

Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 122.

That they hailed from the Kayı branch of the Oğuz confederacy seems to be a creative "rediscovery" in the genealogical concoction of the fifteenth century. It is missing not only in Ahmedi but also, and more importantly, in the Yahşi Fakih-Aşıkpaşazade narrative, which gives its own version of an elaborate genealogical family tree going back to Noah. If there was a particularly significant claim to Kayı lineage, it is hard to imagine that Yahşi Fakih would not have heard of it.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

Based on these charters, all of which were drawn up between 1324 and 1360 (almost one hundred fifty years prior to the emergence of the Ottoman dynastic myth identifying them as members of the Kayı branch of the Oguz federation of Turkish tribes), we may posit that...

- Lindner, Rudi Paul (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Indiana University Press. p. 10.

In fact, no matter how one were to try, the sources simply do not allow the recovery of a family tree linking the antecedents of Osman to the Kayı of the Oğuz tribe. Without a proven genealogy, or even without evidence of sufficient care to produce a single genealogy to be presented to all the court chroniclers, there obviously could be no tribe; thus, the tribe was not a factor in early Ottoman history.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

- Glazer 1996, "War of Independence"

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg: Orient-Institut Istanbul. p. 21-51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University) // CITED: p. 43-44 (PDF p. 45-46/338).

- Findley 2005, p. 115

- Glazer 1996, "Ottoman Institutions"

- Toynbee 1974, pp. 22–23

- Stavrides 2001, p. 20

- Quataert 2005, p. 93

- d'Osman Han 2001, "Ottoman Padishah Succession"

- Quataert 2005, p. 90

- Peirce, Leslie. "The sultanate of women". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- Glazer 1996, "External Threats and Internal Transformations"

- "Son Osmanli vefat etti! (English: Last Ottoman died!)" (in Turkish). September 24, 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Quataert 2005, p. 91

- Quataert 2005, p. 92

- Karateke 2005, pp. 37–54

- Finkel, Caroline (2007). Osman's dream : the history of the ottoman empire. Basic Books. p. 555. ISBN 9780465008506.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. pp. 60, 122.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 153.

- Finkel, Caroline (2007). Osman's dream : the history of the ottoman empire. Basic Books. p. 555. ISBN 9780465008506.

- "Sultan Orhan Gazi". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard (1995). The Cambridge History of Islam: The Indian sub-continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim west. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 320. ISBN 9780521223102. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Sultan Murad Hüdavendigar Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan Yıldırım Beyezid Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- Nicholae Jorga: Geschishte des Osmanichen (Trans :Nilüfer Epçeli) Vol 1 Yeditepe yayınları, İstanbul,2009,ISBN 975-6480 17 3 p 314

- Nicholae Jorga: Geschishte des Osmanichen (Trans :Nilüfer Epçeli) Vol 1 Yeditepe yayınları, İstanbul, 2009, ISBN 975-6480 17 3 p 314

- Joseph von Hammer: Osmanlı Tarihi cilt I (condensation: Abdülkadir Karahan), Milliyet yayınları, İstanbul. p 58-60.

- Prof. Yaşar Yüce-Prof. Ali Sevim: Türkiye tarihi Cilt II, AKDTYKTTK Yayınları, İstanbul, 1991 p 74-75

- Joseph von Hammer: Osmanlı Tarihi cilt I (condensation: Abdülkadir Karahan), Milliyet yayınları, İstanbul. p. 58-60.

- "Sultan Mehmed Çelebi Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Chronology: Sultan II. Murad Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- Kafadar 1996, p. xix

- "Chronology: Fatih Sultan Mehmed Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- "Sultan II. Bayezid Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- Turkish Language Association, (1960), Belleten, p. 467 (in Turkish)

- "Yavuz Sultan Selim Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Kanuni Sultan Süleyman Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Selim Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan III. Murad Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan III. Mehmed Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan I. Ahmed". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan I. Mustafa". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Osman Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan IV. Murad Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan İbrahim Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan IV. Mehmed". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Süleyman Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Ahmed Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Mustafa Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan III. Ahmed Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan I. Mahmud Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan III. Osman Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan III. Mustafa Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan I. Abdülhamit Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan III. Selim Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan IV. Mustafa Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Mahmud Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan Abdülmecid Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan Abdülaziz Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan V. Murad Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan II. Abdülhamid Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan V. Mehmed Reşad Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Sultan VI. Mehmed Vahdettin Han". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- As̜iroğlu 1992, p. 13

- As̜iroğlu 1992, p. 17

- As̜iroğlu 1992, p. 14

- Peirce 1993, pp. 158–159

- M'Gregor, J. (July 1854). "The Race, Religions, and Government of the Ottoman Empire". The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art. Vol. 32. New York: Leavitt, Trow, & Co. p. 376. OCLC 6298914. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- Glassé, Cyril, ed. (2003). "Ottomans". The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. pp. 349–351. ISBN 978-0-7591-0190-6. OCLC 52611080. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- Quataert 2005, pp. 83–85

- Toprak 1981, pp. 44–45

- Mensiz, Ercan. "About Tugra". Tugra.org. Archived from the original on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- Sugar 1993, pp. 23–27

- As̜iroğlu 1992, p. 54

- Glazer 1996, "Table A. Chronology of Major Kemalist Reforms"

- Steffen, Dirk (2005). "Mehmed VI, Sultan". In Tucker, Spencer (ed.). World War I: Encyclopedia. Volume. III: M–R. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 779. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. OCLC 162287003. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- Yerasimos, S. ‘Istanbul’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed March 3, 2020. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1411.

- Yerasimos, S. ‘Istanbul’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed March 3, 2020. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1411.

- Yerasimos, S. ‘Istanbul’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed March 3, 2020. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1411.

- Yerasimos, S. ‘Istanbul’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed March 3, 2020. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1411.

- Zilfi, Madeline C. “The Kadizadelis: Discordant Revivalism in Seventeenth-Century Istanbul”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies Vol. 45, No.4, (October, 1986): 251-269.

- Zilfi, Madeline C. “The Kadizadelis: Discordant Revivalism in Seventeenth-Century Istanbul”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies Vol. 45, No.4, (October, 1986): 251-269.

- Yerasimos, S. ‘Istanbul’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed March 3, 2020. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1411.

- 1. Yerasimos, S. ‘Istanbul’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed March 3, 2020. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1411.

Bibliography

- As̜iroğlu, Orhan Gâzi (1992). Son halife, Abdülmecid. Tarihin şahitleri dizisi (in Turkish). Istanbul: Burak Yayınevi. ISBN 978-9757645177. OCLC 32085609.

- Duran, Tülay (1999). Padişah Portreleri (Portraits of the Ottoman Empire's Sultans) (in Turkish). Sirkeci: Association of Historical Research and Istanbul Research Centre. ISBN 978-9756926079. OCLC 248496159.

- Findley, Carter V. (2005). The Turks in World History. New York: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-517726-8. OCLC 54529318. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- Glazer, Steven A. (1996) [Research completed January 1995]. "Chapter 1: Historical Setting". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). A Country Study: Turkey. Country Studies (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8444-0864-4. OCLC 33898522. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1996). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20600-7. OCLC 55849447. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- Karateke, Hakan T. (2005). "Who is the Next Ottoman Sultan? Attempts to Change the Rule of Succession during the Nineteenth Century". In Weismann, Itzchak; Zachs, Fruma (eds.). Ottoman Reform and Muslim Regeneration: Studies in Honour of Butrus Abu-Manneb. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-757-4. OCLC 60416792. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- d'Osman Han, Nadine Sultana (2001). The Legacy of Sultan Abdulhamid II: Memoirs and Biography of Sultan Selim bin Hamid Han. Foreword by Manoutchehr M. Eskandari-Qajar. Santa Fe, NM: Sultana Pub. OCLC 70659193. Archived from the original on 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2009-05-02.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-508677-5. OCLC 243767445. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Quataert, Donald (2005). The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5. OCLC 59280221. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- Stavrides, Theoharis (2001). The Sultan of Vezirs: The Life and Times of the Ottoman Grand Vezir Mahmud Pasha Angelović (1453–1474). Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-12106-5. OCLC 46640850. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- Sugar, Peter F. (1993). Southeastern Europe under Ottoman Rule, 1354–1804 (3rd ed.). Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-96033-3. OCLC 34219399. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- Toprak, Binnaz (1981). Islam and Political Development in Turkey. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-06471-3. OCLC 8258992. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Uğur, Ali (2007). Mavi Emperyalizm [Blue Imperialism] (in Turkish). Istanbul: Çatı Publishing. ISBN 978-975-8845-87-3. OCLC 221203375. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Toynbee, Arnold J. (1974). "The Ottoman Empire's Place in World History". In Karpat, Kemal H. (ed.). The Ottoman State and Its Place in World History. Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East. 11. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-03945-2. OCLC 1318483. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

External links

- "Website of the 700th Anniversary of the Ottoman Empire". Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Official website of the immediate living descendants of the Ottoman Dynasty". Retrieved 2009-02-06.