Media of the Ottoman Empire

There were multiple newspapers published in the Ottoman Empire.

European influences

The first newspapers in the Ottoman Empire were owned by foreigners living there who wanted to make propaganda about the Western world.[1] The earliest was printed in September 1795 by the Palais de France in Pera (now Beyoğlu), during the embassy of Raymond de Verninac-Saint-Maur. It was issued fortnightly under the title "Bulletin de Nouvelles", until March 1796, it seems. Afterwards, it was published under the name "Gazette française de Constantinople" from September 1796 to May 1797, and "Mercure Oriental" from May to July 1797.[2] Its main purpose was to convey information about the politics of Post-Revolutionary France to foreigners living in Istanbul; therefore, it had little impact on local population.

In 1800, during the French occupation of Egypt, a newspaper in Arabic, al-Tanbih (The Alert), was planned to be issued, with the purpose of disseminating in Egypt the ideals of the French Revolution.[3] It was founded by the general Jacques-François Menou, who appointed Ismail al-Khashab as its editor. However, there is doubt the newspaper was actually ever printed. Menou eventually capitulated after Alexandria was besieged by British forces in 1801.

In 1828, Khedive of Egypt Muhammad Ali ordered, as part of the drastic reforms he was implementing in the province,[lower-alpha 1] the local establishment of the gazette Vekayi-i Misriye (Egyptian Affairs), written in Ottoman Turkish in one column with an Arabic translation in a second column (Ottoman Turkish text was in the right one and Arabic text in the left one). It was later edited in Arabic only, under the Arabic title "al-Waqa'i` al-Misriyya" (The Egyptian Affairs).[5]

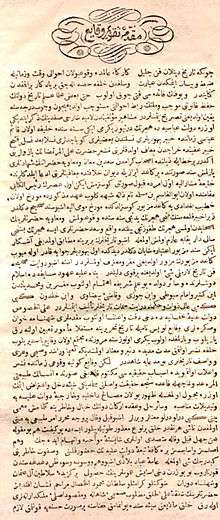

The first official gazette of the Ottoman State was published in 1831, on the order of Mahmud II. It was entitled "Moniteur ottoman", perhaps referring to the French newspaper Le Moniteur universel. Its weekly issues were written in French and edited by Alexandre Blacque at the expense of the Porte. A few months later, a firman of the sultan ordered that a Turkish gazette be published under the named "Takvim-i Vekayi" (Calendar of Affairs), which would be effectively translating the Moniteur ottoman, and issued irregularly until November 4, 1922. Laws and decrees of the sultan were published in it, as well as descriptions of court festivities.

The first non-official Turkish newspaper, Ceride-i Havadis (Register of Events), was published by an Englishman, William Churchill, in 1840. The first private newspaper to be published by Turkish journalists, Tercüman-ı Ahvâl (Interpreter of Events), was founded by İbrahim Şinasi and Agah Efendi and issued in October 1860; the owners stated that "freedom of expression is a part of human nature", thereby initiating an era of free press as inspired by the ideals of 18th century French Enlightenment.[6] In the meantime, the first private newspaper written solely in Arabic, Mir'at al-ahwal, had been founded by a Syrian poet, Rizqallah Hassun, in 1855, but it had been suspended a year later by Ottoman authorities because of its critical tone regarding their policies. Subsequently, several newspapers flourished in the provinces. A new press code inspired by French law, Matbuat Nizamnamesi, was issued in 1864, accompanied by the establishment of a censorship office.[6]

When Sultan Abdulhamid II revoked the constitution, Ottomans established newspapers based in foreign countries as they felt they could no longer operate freely in the empire.[7] Elisabeth Kendall, author of "Between Politics and Literature: Journals in Alexandria and Istanbul at the End of the Nineteenth Century," wrote that therefore by the 1880s "purer cultural journalism" became the focus of publications that remained in the imperial capital.[8]

By city

The Ottoman capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul), was the centre of the press activity.[9]

In 1876 there were forty-seven journals published in Constantinople. Most were in minority and foreign languages, and thirteen of them were in Ottoman Turkish.[10] Many newspapers in non-Muslim minority and foreign languages were produced in Galata, with production in daylight hours and distribution at nighttime; Ottoman authorities did not allow production of the Galata-based newspapers at night.[11]

Kendall wrote that Constantinople by the 1870s lacked specialised literary journals found in Alexandria, Egypt. What journals that were in Constantinople had a general focus,[12] and Kendall stated that the potential audience base being "extremely limited" frustrated the development of these journals.[7] An 1875 stamp duty caused, in Kendall's eyes, "more marginal" ones to vanish.[7]

After the fall of the Ottoman Empire Constantinople, now Istanbul, remained the centre of Turkish journalism.[9]

Turkish

Vekayi-i giridiyye, a newspaper published in Egypt after 1830, was the first newspaper in the Turkish language in the empire. It also had a bilingual Turkish-Greek version.[13] Johann Strauss, author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," wrote that the press in Ottoman Turkish began to "rise" after 1860, after press in Christian languages had already developed.[14]

Ottoman Turkish publications included:

- Basiret[15]

- Ceride-i-Havadis, which included a supplement called Ruzname Ceride-i-Havadis. It was the first privately published Ottoman Turkish publication in the Ottoman Empire. A person from England established it.[10]

- Hürriyet[15]

- İkdam

- La Pédiatrie en Turquie - Türkiye'de Emraz-ı Etfal[16]

- Mecmua i-Ebüzziya, established by Tevfik Ebüzziya in 1880 and running until 1887, then restarting in 1894, and ending in 1912.[8]

- Mecmua i-İbretnüma (Constantinople) - Published from 1865 to 1866 in Cemiyet-i Kitabet, it had sixteen issues.[7]

- Mecmua İber-u İntibah - In operation from 1862 to 1864, according to Kendall, it was the "first specialized literary journal" to ever be published in Turkey. The total number of issues is eight.[7]

- Muharrir (Constantinople) - In operation from 1876 to 1878, it was operated by Ebüzziya Tevfik and had a total of eight issues.[7]

- Ravzat-ül Maarif (Constantinople) - Published from 1870 to 1871, focusing on science and literature, it had six issues.[7]

- Servet - Established by ethnic Greek journalist Demetrius Nicolaides in 1889[17]

- Servet i-Fünun[18] - It was at first a supplement of Servet.[17]

- Takvim-i Vekayi

- Terakki[15]

- Tercüman i-Hakikat - Established in 1878 by Ahmed Midhat[8]

- Türk İktisad Mecmuası - Revue Économique de Turquie[19]

There was a Karamanli Turkish (Turkish in Greek characters) publication, Anatoli, published from 1850 to 1922,[20] made by Evangelinos Misalaidis. Other publications in Karamanli were Anatol Ahteri (Ανατόλ Αχτερί), Angeliaforos, Angeliaforos coçuklar içun, Şafak (Σαφάκ), and Terakki (Τερακκή). The second and third were created by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Demetrius Nicolaides also applied to make his own Karamanli publication, Asya ("Asia"), but was denied. Evangelina Baltia and Ayșe Kavak, authors of "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century," wrote that they could find no information explaining why Nicolaides' proposal was turned down.[21]

Arabic

The first Arabic-language newspaper in Egypt was al-Tanbih, published by the French, and headquartered in Alexandria, around the start of the 1800s.[10]

The first official Egyptian newspaper, in Arabic and based in Cairo, was Jurnāl al-Khidīw and appeared over ten years after al-Tanbih.[10]

The Arabic newspaper Al-Jawāʾib began in Constantinople, established by Fāris al-Shidyāq a.k.a. Ahmed Faris Efendi (1804-1887), after 1860. It published Ottoman laws in Arabic,[14] including the Ottoman Constitution of 1876.[22]

Several provincial newspapers (vilayet gazeteleri in Turkish) were in Arabic.[14] The first such newspaper was Ḥadīqat al-Akhbār, described by Johann Strauss, author of "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," as "semi-official".[23] Published by Khalīl al-Khūrī (1836 – 1907), it began in 1858.[24] Others include the Tunis-based Al-Rāʾid at-Tūnisī and a bilingual Ottoman Turkish-Arabic paper in Iraq, Zevra / al-Zawrāʾ; the former was established in 1860 and the latter in 1869. Strauss said the latter had "the highest prestige, at least for a while" of the provincial Arabic newspapers.[25]

Strauss, also author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," stated that "some writers" stated that versions of the Takvim-i Vekayi in Arabic existed.[13]

Armenian

- Jamanak

- Takvim-i Vekayi Armenian version[13]

Bulgarian

Bulgarian newspapers in the late Ottoman period published in Constantinople were Makedoniya, Napredŭk or Napredǎk ("Progress"), Pravo,[15] and Turtsiya; Strauss described the last one as "probably a Bulgarian version of [the French-language paper] La Turquie."[26]

Other Bulgarian newspapers included the official newspaper of Danube Vilayet, Dunav/Tuna; Iztočno Vreme; and one published by Protestant Christian missionaries from the United States, Zornitsa ("Morning Star"). Strauss wrote that Iztočno Vreme was "a sort of Bulgarian edition of the Levant Times".[27]

Greek

There was a bilingual Turkish-Greek version of Vekayi-i giridiyye (Κρητική Εφημερίς in Greek).[13]

There was a Greek-language newspaper established in 1861, Anatolikos Astēr ("Eastern Star"). Konstantinos Photiadis was the editor in chief,[28] and Demetrius Nicolaides served as an editor.[17]

In 1867 Nicolaides established his own Greek-language newspaper, Kōnstantinoupolis. Johann Strauss, author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," wrote that the publication "was long to remain the most widely read Greek paper in the Ottoman Empire."[17]

During periods when Kōnstantinoupolis was not in operation Nicolaides edited Thrakē ("Thrace"; August 1870 – 1880) and Avgi ("Aurora"; 6 July 1880 – 10 July 1884).[29]

Also:

- Chrysalis[30]

- Pandora[30]

- Takvim-i Vekayi Greek version[13]

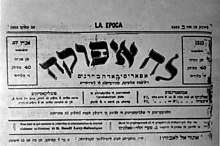

Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino)

In 1860 Jurnal Yisraelit was established by Yehezkel Gabay (1825-1896). Johann Strauss stated that he was perceived as a founder of the practice of journalism within the Turkish Jewish community.[31]

Persian

There was a Persian-language paper, Akhtar ("The Star"), which was established in 1876 and published Persian versions of Ottoman government documents, including the 1876 Constitution.[14]

Strauss stated that "some writers" stated that versions of the Takvim-i Vekayi in Persian existed.[13]

Western languages

French

The French had also established a newspaper in Constantinople in 1795, but it closed as French journalists moved their base to Alexandria, Egypt after the French campaign in Egypt and Syria.[10]

The cities of Constantinople (Istanbul), Beirut, Salonika (Thessaloniki), and Smyrna (İzmir) had domestically-published French-language newspapers.[32] The publications were also active in the eastern Mediterranean Sea area.

Non-Muslim ethnic minorities in the empire used French as a lingua franca and therefore used these publications. In addition French businesspeople and vocational workers used French-language media to get in touch with clients in the empire.[33] [33] French-language journalism was initially centred in Smyrna but by the 1860s it began shifting towards Constantinople.[10] In addition, newspapers written in other western European languages had editions in French or editions with portions in French.[32] In the history of the empire over 400 titles of periodicals were partially or entirely in the French language, with about 66% fully in French and the rest with other languages; the total includes about 131 titles from Ottoman Egypt.[33] Takvim-i Vekayi had versions in French.[13]

Non-Muslim ethnic minorities in the empire used French as a lingua franca and therefore used these publications. In addition French businesspeople and vocational workers used French-language media to get in touch with clients in the empire.[33]

Lorans Tanatar Baruh of SALT and Sara Yontan Musnik of the National Library of France stated that the post-1918 Ottoman government favored the French-language media.[33] The use of French continued by the time the empire ended in 1923, and remained for about a decade more in the Republic of Turkey.[33]

French-language publications included:

- Annonces-Journal de Constantinople (Constantinople)[34]

- Annuaire des commerçants de Smyrne et de l'Anatolie (Smyrna)[35]

- Annuaire oriental du commerce (Constantinople)[36]

- L'Aurore (Constantinople) - A Zionist-funded Jewish newspaper[37]

- Correspondance d'Orient [38]

- Courrier de Constantinople : moniteur du commerce (Constantinople)[39]

- Gazette Médicale d'Orient[40]

- Génie Civil Ottoman[41]

- Hadikat-el-Akhbar. Journal de Syrie et Liban, the French edition of Ḥadīqat al-Akhbār[42]

- Journal de Constantinople (Constantinople)[43]

- Journal de Constantinople et des intérêts orientaux[44]

- Journal de Salonique (Salonika)[45]

- Journal de Smyrne (Smyrna)[46]

- L'Abeille du Bosphore[47]

- L'Étoile du Bosphore[48]

- La Décade égyptienne[49]

- La Patrie : Journal ottoman publié en français politique, littéraire, scientifique, industriel, financier et commerciel illustré (Constantinople)[50]

- La Pédiatrie en Turquie - Türkiye'de Emraz-ı Etfal[16]

- La Turquie. Journal politique, commercial, industriel et financier[51]

- La Turquie (Constantinople)[52]

- Strauss described it as "semi-official" and "One of the principal French language papers published in Istanbul."[53]

- Le Courier de l'Égypte (spelled with one or two "r"s)[49]

- Le Moniteur Ottoman[10]

- Le Phare d'Alexandrie (Alexandria) - Began in 1842. Kendall stated that since the newspaper existed for a "long" period of time, its notability stemmed from "its steady stimulation of Alexandrian culture" in its period.[10]

- Le Phare du Bosphore (Constantinople) - Established in 1870, it was edited by Kiriakopoulos.[10] Strauss wrote in "Twenty Years in the Ottoman capital: the memoirs of Dr. Hristo Tanev Stambolski of Kazanlik (1843-1932) from an Ottoman point of view" that it was "oriented towards Greek interests".[15] It moved to Egypt, and ended in 1890.[10]

- Le Stamboul (Constantinople)

- The Levant Herald[54]

- The Levant Times and Shipping Gazette (Constantinople) - In French and English[55]

- Miscellanea Ægyptica (Alexandria) - Established in 1843, published by the Association littéraire d'Egypte, the first cultural-centred publication in Egypt[10]

- Revue Bibliographique de Philologie et d'Histoire[56]

- Türk İktisad Mecmuası - Revue Économique de Turquie[19]

- Revue commerciale du Levant (Constantinople) - of the French chamber of commerce[57]

- Revue Médico-Pharmaceutique[58]

- Stamboul - Kendall wrote that when Regis Delbeuf, a literature teacher from France, became the editor, the publication experienced "the greatest cultural impact".[10]

Other Western languages

There were two English-French papers: The Levant Herald and The Levant Times and Shipping Gazette.[55][54]

Levant Trade Review, by the American Chamber of Commerce, is another English publication.[59]

There was an Italian newspaper established in the city of Alexandria in 1858 and 1859, known as Il Progreso.[10]

Language unknown

The first theatre journal in Turkey, established in 1874, was Tiyatro. Agop Baronyan created it.[7]

See also

- History of Middle Eastern newspapers

For modern-day territories once a part of the empire:

- Media of Albania

- Media of Bulgaria

- Media of Egypt

- Media of Greece

- Media of Iraq

- Media of Israel

- Media of Jordan

- Media of Lebanon

- Media of Libya

- Media of North Macedonia

- Media of Saudi Arabia (for publications in the modern day Hejaz region)

- Media of Syria

- Media of Turkey

- Media of Yemen

Notes

Sources

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (2008). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0816062591.

- E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. 1987.

- Groc, Gérard; Çağlar, İbrahim (1985). La presse française de Turquie de 1795 à nos jours : histoire et catalogue (in French).

- Kendall, Elisabeth (2002). "Between Politics and Literature: Journals in Alexandria and Istanbul at the End of the Nineteenth Century". In Fawaz, Leila Tarazi; C. A. Bayly (eds.). Modernity and Culture: From the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press. pp. 330-. ISBN 9780231114271. - Also credited: Robert Ilbert (collaboration). Old ISBN 0231114273.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000) [first published 1958]. The Balkans since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-0814797662.*Wendell, Charles. The Evolution of the Egyptian National Image. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520021112.

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University)

- Tripp, Charles, ed. (1993). Contemporary Egypt: Through Egyptian Eyes. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415061032.

References

- Stavrianos, p. 211.

- Groc & Çağlar, p. 6.

- Wendell, p. 143.

- E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, p. 952.

- Tripp (ed.), p. 2; Amin, Fortna & Frierson, p. 99; Hill, p. 172.

- Ágoston & Masters, p. 433.

- Kendall, p. 338.

- Kendall, p. 340.

- Kendall, p. 339.

- Kendall, p. 331.

- Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (2018-02-28). "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. - Volume 12 of Bamberger Orientstudien - Old ISBN 3863095278 // Cited: p. 40

- Kendall, p. 337.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 22 (PDF p. 24)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 25 (PDF p. 27)

- Strauss, Johann. "Twenty Years in the Ottoman capital: the memoirs of Dr. Hristo Tanev Stambolski of Kazanlik (1843-1932) from an Ottoman point of view." In: Herzog, Christoph and Richard Wittmann (editors). Istanbul - Kushta - Constantinople: Narratives of Identity in the Ottoman Capital, 1830-1930. Routledge, 10 October 2018. ISBN 1351805223, 9781351805223. p. 267.

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129145

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 29 (PDF p. 31)

- Kendall, p. 330. CITED: p. 342.

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129260

- Michael, Michalis N.; Börte Sagaster; Theoharis Stavrides (2018-02-28). "Introduction". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. v-. ISBN 9783863095277. Cited: p. xi

- Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (2018-02-28). Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives. Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. // Cited: p. 42

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 34 (PDF p. 36)

- Strauss, Johann. "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire" (Chapter 7). In: Murphey, Rhoads (editor). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Routledge, 7 July 2016. (ISBN 1317118448, 9781317118442), Google Books PT192.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 26 (PDF p. 28)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 25-26 (PDF p. 27-28)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 36.

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Cited: p. 34 (PDF p. 36)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 32 (PDF p. 34)

- Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (2018-02-28). "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. - Volume 12 of Bamberger Orientstudien - Old ISBN 3863095278 // Cited: p. 37

- Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (2018-02-28). "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. - Volume 12 of Bamberger Orientstudien - Old ISBN 3863095278 // Cited: p. 34

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 24 (PDF p. 26)

- Strauss, Johann. "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire" (Chapter 7). In: Murphey, Rhoads (editor). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Routledge, 7 July 2016. (ISBN 1317118456, 9781317118459), p. 122.

- Baruh, Lorans Tanatar; Sara Yontan Musnik. "Francophone press in the Ottoman Empire". French National Library. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32695298v/date?rk=21459;2 // city from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6738667f?rk=21459;2

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32696967r/date.item // city from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5814716q?rk=21459;2

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32698490c/date?rk=42918;4 // city from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9341936?rk=21459;2

- O'Malley, JP (2018-09-07). "Before the Holocaust, Ottoman Jews supported the Armenian genocide's 'architect'". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32748631j/date?rk=64378;0

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32750239g/date?rk=107296;4 // city from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4530064r.item

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129124 and https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129469 and https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129267 and https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129327

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129179 and https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129075

- Strauss, Johann. "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire" (Chapter 7). In: Murphey, Rhoads (editor). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Routledge, 7 July 2016. (ISBN 1317118448, 9781317118442), Google Books PT192 and PT193.

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32797343h/date?rk=128756;0 // https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k67394991/f1.item.zoom

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32797344v/date?rk=150215;2

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32798884q/date?rk=171674;4 // https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6738670x.item

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb327989186/date?rk=193134;0 // https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k934188r?rk=21459;2

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb326806914/date?rk=214593;2

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32770311s/date?rk=236052;4

- "Titres de presse francophone en Égypte". French National Library. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb328337903/date?rk=386268;0 // city from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9341813

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129291

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4528495w.item

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Cited: p. 36 (PDF p. 38)

- Bradshaw's Continental Railway, Steam Transit, and General Guide, for Travellers Through Europe. W.J. Adams, 1875. p. 657.

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k979136m.item

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129289

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k67403713.item

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129377 and https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/129426

- Levant Trade Review, Volume 4. American Chamber of Commerce, 1914. p. 110.

Further reading

- Koloğlu, Orhan (1992). "La presse turque en Crète". In Clayer, Nathalie; Alexandre Popovic; Thierry Zarcone (eds.). Presse turque et presse de Turquie. Actes des colloques d’Istanbul. Istanbul-Paris: Isis. pp. 259–267.

External links

- Baruh, Lorans Tanatar; Sara Yontan Musnik. "Francophone press in the Ottoman Empire". National Library of France.