Persecution of Muslims during Ottoman contraction

Persecution of Ottoman Muslims during the Ottoman Contraction refers to the persecution, massacre, or ethnic cleansing of Muslims (including Albanians, Bosniaks, Serbs, Greeks, Pomaks, Circassians, Ottoman Turks and others) by non-Muslims during the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.[1] The 19th century saw the rise of nationalism in the Balkans coincident with the decline of Ottoman power, which resulted in the establishment of an independent Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria. At the same time, the Russian Empire expanded into previously Ottoman-ruled or Ottoman-allied regions of the Caucasus and the Black Sea region. Muslims in these countries suffered, with many dying during the conflicts or becoming refugees. The persecution of Muslims was continued during World War I by the invading Russian troops in the east and during the Turkish War of Independence in the west, east, and south of Anatolia. After the Greco-Turkish War, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey took place, and most Greek Muslims left. During these times many Muslim refugees, called Muhacir, settled in Turkey.

| Freedom of religion | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Status by country

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Religion portal | ||||||||||||

Background

Turkish presence and Islamisation of native peoples in the Balkans

For the first time, Ottoman military expeditions shifted from Anatolia to Europe and the Balkans with the occupation of the Gallipoli peninsula in the 1350s.[2] After the region was conquered by the Muslim Ottoman Empire, the Turkish presence grew. Some of the settlers were Yörüks, nomads who quickly became sedentary, and others were from urban classes. They settled in almost all of the towns, but the majority of them settled in the Eastern Balkans. The main areas of settlement were Ludogorie, Dobrudzha, the Thracian plain, the mountains and plains of northern Greece and Eastern Macedonia around the Vardar river.

Between the 15th and 17th centuries, large numbers of native Balkan peoples converted to Islam. Places of mass conversions were in Bosnia, Albania, Crete, and the Rhodope Mountains.[3] Some of the native population converted to Islam and became Turkish over time, mainly those in Anatolia.[4]

Motives for persecution

Hall points out that atrocities were committed by all sides during the Balkan conflicts. Deliberate terror was designed to instigate population movements out of particular territories. The aim of targeting the civilian population was to carve ethnically homogeneous countries.[5]

Great Turkish War

Even before the Great Turkish War (1683—1699) Austrians and Venetians supported Christian irregulars and rebellious highlanders of Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania to raid Muslim Slavs.[6]

The end of the Great Turkish War marked the first time the Ottoman Empire lost large areas of territory to Christians. Most of Hungary, Podolia, and the Morea was lost. The Ottomans regained the Morea quickly, and Muslims soon became part of the population or were never thoroughly displaced in the first place.

Most of the Christians who lived in the Ottoman Empire were Orthodox so Russia was particularly interested in them. In 1711 Peter the Great invited Balkan Christians to revolt against Ottoman Muslim rule.[7]

Croatia

About one quarter of all people living in Slavonia in the 16th century were Muslims who mostly lived in towns, with Osijek and Požega being the largest Muslim settlements.[8] Like other Muslims who lived in Croatia (Lika and Kordun) and Dalmatia, they were all forced to leave their homes by the end of 1699. This was the first example of the cleansing of Muslims in this region. This cleansing of Muslims "enjoyed the benediction of Catholic church". Around 130,000 Muslims from Croatia and Slavonia were driven to Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina.[9][10] Basically, all Muslims who lived in Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia were either forced to exile, murdered or enslaved.[11]

Thousands of Serb refugees crossed Danube and populated territories of Habsburg Monarchy left by Muslims. Leopold I granted ethno-religious autonomy to them without giving any privileges to the remaining Muslim population who therefore fled to Bosnia, Herzegovina and Serbia spreading anti-Christian sentiment among other Muslims there.[12] The relations between non-Muslim and Muslim population of Ottoman held Balkans became progressively worse.[13]

At the beginning of the 18th century remaining Muslims of Slavonia moved to Posavina.[14][15] The Ottoman authorities encouraged hopes of expelled Muslims for a quick return to their homes and settled them in the border regions.[16] The Muslims comprised about 2/3 population of Lika. All of them, like Muslims who lived in other parts of Croatia, were forced to convert to Catholicism or to be expelled.[17] Almost all buildings that belonged to Muslim religion and culture were destroyed in the region of Croatia after Muslims had to leave it.[18]

Northern Bosnia

In 1716, Austria occupied northern Bosnia alongside northern Serbia until 1739 when those lands were ceded back to the Ottoman Empire at the Treaty of Belgrade. During this era, the Austrian Empire outlined its position to the Bosnian Muslim population about living within its administration. Two options were offered by Charles VI such as a conversion to Christianity while retaining property and remaining on Austrian territory, or for a departure of those remaining Muslim to other lands.[19]

Montenegro

At the beginning of the 18th century (1709 or 1711) Orthodox Serbs massacred their Muslim neighbors in Montenegro.[20][21]

National movements

Serbian Revolution

After the Dahije, renegade janissaries who defied the Sultan and ruled the Sanjak of Smederevo in tyranny (beginning in 1801), imposing harsh taxes and forced labour, went on to execute leading Serbs throughout the sanjak in 1804, the Serbs rose up against the Dahije. The revolt, known as the First Serbian Uprising, subsequently reached national level after the quick success of the Serbs. The Porte, seeing the Serbs as a threat, ordered their disbandment. The revolutionaries took over Belgrade in 1806 where an armed uprising against a Muslim garrison, including civilians, took place.[22] During the uprising urban centers with sizeable Muslim populations were violently targeted such as Užice and Valjevo, as the Serbian peasantry held a class hatred of the urban Muslim elite.[23][24] In the end, Serbia became an autonomous country with most of the Muslims been expelled.[25] During the revolts 15,000–20,000 Muslims fled or were expelled.[26] In Belgrade and the rest of Serbia there remained a Muslim population of some 23,000 who were also forcibly expelled after 1862, following a massacre of Serbian civilians by Ottoman soldiers near Kalemegdan.[24][27] Some Muslim families then migrated and resettled in Bosnia, where their descendants today reside in urban centres such as Šamac, Tuzla, Foča and Sarajevo.[28][29]

Greek Revolution

In 1821, a major Greek revolt broke out in Southern Greece. Insurgents gained control of most of the countryside while the Muslims fled to the fortified towns and castles.[30] Each one of them was besieged and gradually through starvation or surrender most were taken over by the Greeks. In the massacres of April 1821 some 15,000 were killed.[30] The worst massacre happened in Tripolitsa, some 8,000 Muslims and Jews died.[30] In the end an Independent Greece was set up. Most of the Muslims in its area had been killed or expelled during the conflict.[30]

Russo-Turkish war

Bulgaria

The Bulgarian uprising eventually lead to a war between Russia and the Ottomans. Russia invaded the Ottoman Balkans through Dobrudzha and northern Bulgaria attacking the Muslim population. In this war the Ottomans were defeated and in the process a large part of the Turks of Bulgaria fled to Anatolia and Constantinople. It was a cold winter and a large part of them died. Some of them returned after the war but most of these left again. The Bulgarian Muslims (part of them Turks) settled mostly around the Sea of Marmara. Some of them had been wealthy and they played an important part in the Ottoman elite in later years. Almost half of the pre-war 1,5 million Muslim population of Bulgaria was gone, an estimated 200,000 died and the rest fled.[32]

Migration continued in the peacetime, some 350,000 Bulgarian Muslims left the country between 1880 and 1911.[33]

Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78)

On the eve of the outbreak of a second round of hostilities between Serbia and the Ottoman Empire in 1877, a notable Muslim population existed in the districts of Niš, Pirot, Vranje, Leskovac, Prokuplje and Kuršumlija.[34] The rural parts of Toplica, Kosanica, Pusta Reka and Jablanica valleys and adjoining semi-mountainous interior was inhabited by compact Muslim Albanian population while Serbs in those areas lived near the river mouths and mountain slopes and both peoples inhabited other regions of the South Morava river basin.[35][36] The Muslim population of most of the area was composed out of ethnic Gheg Albanians and with Turks located in urban centres.[37] Part of the Turks were of Albanian origin.[38] The Muslims in the cities of Niš and Pirot were Turkish-speaking; Vranje and Leskovac were Turkish- and Albanian-speaking; Prokuplje and Kuršumlija were Albanian-speaking.[37] There was also a minority of Circassian refugees settled by the Ottomans during the 1860s, near the then border around the environs of Niš.[39] Estimates vary on the size of the Muslim population on the eve of the war within these areas ranging from as high as 200, 000 to as low as 131,000.[40][41][42] Estimates as to the number of the Muslim refugees that left the region for the Ottoman Empire due to the war range from 60–70,000 to as low as 30,000.[43][44][45][46][47][48] The departure of the Albanian population from these regions was done in a manner that today would be characterized as ethnic cleansing.[49]

Hostilities between Serbian and Ottoman forces broke out on 15 December 1877, after a Russian request for Serbia to enter the Russo-Turkish war.[50] The Serbian military had two objectives: capturing Niš and breaking the Niš-Sofia Ottoman lines of communication.[51] Serbian forces entered the wider Toplica and Morava valleys capturing urban centres such as Niš, Kuršumlija, Prokuplije, Leskovac, and Vranje and their surrounding rural and mountainous districts.[52] In these regions, the Albanian population depending on the area they resided had fled into nearby mountains, leaving livestock, property and other belongings behind.[53] Some Albanians returned and submitted to Serbian authorities, while others continued their flight southward toward Ottoman Kosovo.[54] Serbian forces also encountered heavy Albanian resistance in certain areas which slowed their advance into these regions resulting in having to take villages one by one that became vacant.[55] A small Albanian population remained the Medveđa area, where their descendants still reside today.[56] The retreat of these refugees toward Ottoman Kosovo was halted at the Goljak Mountains when an armistice was declared.[55] The Albanian population was resettled in Lab area and other parts of northern Kosovo alongside the new Ottoman-Serbian border.[57][58][59] Most Albanian refugees were resettled in over 30 large rural settlements in central and southeastern Kosovo and in urban centres that increased their populations substantially.[57][42][60] Tensions between Albanian refugees and local Kosovo Albanians arose over resources, as the Ottoman Empire found it difficult to accommodate to their needs and meager conditions.[61] Tensions in the form of revenge attacks also arose by incoming Albanian refugees on local Kosovo Serbs that contributed to the beginnings of the ongoing Serbian-Albanian conflict in coming decades.[49][61][62]

Bosnia

In 1875 a conflict between Muslims and Christians broke out in Bosnia. After the Ottoman Empire signed the treaty at the 1878 Berlin Congress, Bosnia was occupied by Austria-Hungary.[63] Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) perceived this as a betrayal by the Ottomans and left on their own, felt that they were defending their homeland and not the wider Empire.[63] From 9 July until 20 October 1878 or for almost three months, Bosnian Muslims resisted Austro-Hungarian forces in nearly 60 military engagements with 5000 casualties either wounded or killed.[63] Some Bosnian Muslims concerned about their future and well being under the new non-Muslim administration, left Bosnia for the Ottoman Empire.[63] From 1878 until 1918, between 130,000[64] and 150,000 Bosnian Muslims departed Bosnia to areas under Ottoman control, some to the Balkans, others to Anatolia, the Levant and Maghreb.[65] Today, these Bosnian populations in the Arab world have become assimilated although they have retained memories of their origins and some bear the ethnonym Bosniak (rendered in Arabic as Bushnak) as a surname.[66][67][68]

Caucasus

The war continued in the east and after the peace area around Kars was ceded to Russia. This resulted in a large number of Muslims leaving and settling in remaining Ottoman lands. Batum and its surrounding area was also ceded to Russia causing many local Georgian Muslims to migrate to the west.[69] Most of them settled around the Anatolian Black Sea coast.

Balkan Wars

In 1912 Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro declared war on the Ottomans. The Ottomans quickly lost territory. According to Geert-Hinrich Ahrens, "the invading armies and Christian insurgents committed a wide range of atrocities upon the Muslim population."[70] In Kosovo and Albania most of the victims were Albanians while in other areas most of the victims were Turks and Pomaks. A large number of Pomaks in the Rhodopes were forcibly converted to Orthodoxy but later allowed to reconvert, most of them did.[71] During this war hundreds of thousands of the Turks and Pomaks fled their villages and became refugees.[72] Salonika (Thessaloniki) and Adrianople (Edirne) were crowded with them. By sea and land mostly they settled in Ottoman Thrace and Anatolia.

World War I and the Turkish War of Independence

Caucasus Campaign

Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör noted that during the Russian invasion of Ottoman lands, "many atrocities were carried out against the local Turks and Kurds by the Russian army and Armenian volunteers."[73] A large part of the local Muslim Turks and Kurds fled west after the Russian invasion of 1916.[74] According to J. Rummel at least 128,000 Muslims were killed by Russian troops and Armenian irregulars during the period between 1915–1916. A further 40,000 Muslims were killed by Armenian troops in the region occupied by Russian troops between 1917 and 1918.[75]

Franco-Turkish War

Cilicia was occupied by the British after World War I, who were later replaced by the French. The French Armenian Legion armed returning Armenian refugees of the Armenian Genocide to the region and assisting them. Eventually the Turks responded with resistance against the French occupation, battles took place in Marash, Aintab, and Urfa. Most of these cities were destroyed during the process with large civilian suffering. In Marash, 4.500 Turks died.[76] The French left the area together with the Armenians after 1920. The retribution for the Armenian Genocide served as justification for armed Armenians.[74]

Greco–Turkish War

After the Greek landing and the following occupation of Western Anatolia after World War I during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) the Turkish resistance activity was answered with terror against the local Muslims. Killings, rapes, and village burnings took place as the Greek Army advanced.[78] Historian Taner Akçam noted that a British officer reported as follows:[79]

The National forces were established solely for the purpose of fighting the Greeks..,. The Turks are willing to remain under the control of any other state.,.. There was not even an organized resistance at the time of the Greek occupation. Yet the Greeks are persisting in their oppression, and they have continued to burn villages, kill Turks and rape and kill women and young girls and throttle to death children.

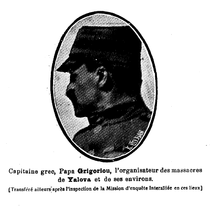

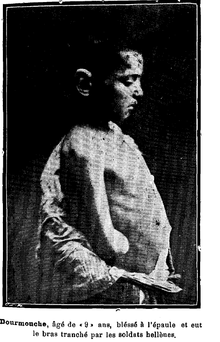

During the Greek occupation, Greek troops and local Greeks, Armenian, and Circassian groups committed the Yalova Peninsula Massacres in early 1921 against the local Muslim population.[80] These resulted, according to some sources, in the deaths of c. 300 of the local Muslim populace, as well c. 27 villages.[81][82] Precise number of casualties is not exactly known. Statements gathered by Ottoman official, reveal a relatevely low number of casualties: based on the Ottoman enquiry to which 177 survivors responded, only 35 were reported as killed, wounded or beaten or missing. This is also in accordance with Toynbee's accounts that one to two murders were enough to drive out the population.[83] Another source estimates that barely 1.500 Muslims out of 7,000 survived in the environment of Yalova.[84]

The Greeks advanced all the way to Central Anatolia. After the Turkish attack in 1922 the Greeks retreated and Norman M. Naimark notes that "the Greek retreat was even more devastating for the local population than the occupation".[85] During the retreat, towns and villages were burned as part of a scorched earth policy, accompanied with massacres and rapes. During this war, a part of Western Anatolia was destroyed, large towns such as Manisa, Salihli together with many villages being burned.[86] The Inter-Allied commission, consisting of British, French, American and Italian officers found that "there is a systematic plan of destruction of Turkish villages and extinction of the Muslim population."[87]

The peace after the Greco–Turkish War resulted in a mutual population exchange between Greece and Turkey, between the two countries. As a result, the Muslim population of Greece, with the exception of Western Thrace, was relocated to Turkey.[88]

Total casualties

Death toll

According to historian Justin McCarthy, between the years 1821–1922, from the beginning of the Greek War of Independence to the end of the Ottoman Empire, five million Muslims were driven from their lands and another five and one-half million died, some of them killed in wars, others perishing as refugees from starvation or disease.[1]

According to Michael Mann McCarthy is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate over Balkan Muslim death figures.[89] Mann however states that even if those figures were reduced "by as much as 50 percent, they still would horrify".[89] In the discussion about the Armenian Genocide, McCarthy denies the genocide and is considered as the leading pro-Turkish scholar.[90][91] Scholarly critics of McCarthy acknowledge that his research on Muslim civilian casualties and refugee numbers (19th and early 20th centuries) has brought forth a valuable perspective, previously neglected in the Christian West: that millions of Muslims and Jews also suffered and died during these years.[92][93] Donald W. Bleacher, though acknowledging that McCarthy is pro-Turkish nonetheless has called his scholarly study Death and Exile on Muslim civilian casualties and refugee numbers "a necessary corrective" challenging the West's model of all victims being Christians and all perpetrators as being Muslims.[93]

Historian Mark Biondich estimates that from 1878-1912 up to two million Muslims left the Balkans either voluntarily or involuntarily while Muslims casualties in the Balkans during 1912-1923 within the context of those killed and expelled exceeded some three million.[94]

Total Muslim deaths and refugees during these centuries are estimated to be several millions.[95] It is estimated that during the last decade of the Ottoman Empire (1912–1922) when the Balkan wars, World War I and war of Independence took place, close to 2 million Muslims, civilian and military, died in the area of modern Turkey.[96]

The forced mass displacement of Muslims out of the Balkans during the era of territorial contraction of the Ottoman Empire has only become a topic of recent scholarly interest in the 21st century.[97]

Settlement of refugees

The Ottoman authorities and charities provided some help to the immigrants and sometimes settled them in certain locations. In Turkey most of the Balkan refugees settled in Western Turkey and Thrace. The Caucasians, in addition to these areas also settled in Central Anatolia and around the Black Sea coast. Eastern Anatolia was not largely settled with the exception of some Circassian and Karapapak villages. There were also completely new villages founded by refugees, for example in uninhabited forested areas. Many people of the 1924 exchange were settled in former Greek villages along the Aegean coast. Outside of Turkey, Circassians were settled along the Hedjaz Railway and some Cretan Muslims at Syria's coast.

Destruction of Muslim heritage

Muslim heritage was extensively targeted during the persecutions. During their long rule the Ottomans had built numerous mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, bath-houses and other types of buildings. According to current research, around 20,000 buildings of all sizes have been documented in official Ottoman registers.[98] However very few survives of this Ottoman heritage in most of the Balkan countries.[99] Most of the Ottoman era mosques of the Balkans have been destroyed and from the ones still standing at least their minarets. Before the Habsburg conquest, Osijek had 8–10 mosques none of which remain today.[100] During the Balkan wars there were cases of desecration, destruction of mosques and Muslim cemeteries.[100] Of the 166 Madrasas in the Ottoman Balkans in the 17th century only 8 remain and 5 of them are near Edirne.[98] The amount of destruction was 95–98%.[98] The same is also valid for other types of buildings, such as markethalls, caravanserais and baths.[98] From a chain of caravanserais across the Balkans only one is preserved while there are vague ruins of four others.[98] There were in the area of Negroponte in 1521: 34 large and small mosques, 6 hamams, 10 schools, 6 dervish convents. Today only the ruin of one hamam remains.[98]

| Town | During Ottoman rule | Still standing |

|---|---|---|

| Shumen | 40 | 3 |

| Serres | 60 | 3 |

| Belgrade | >100 | 1 |

| Sofia | >100 | 1 |

| Ruse | 36 | 1 |

| Sremska Mitrovica[101] | 17 | 0 |

| Osijek[102] | 7 | 0 |

| Požega[103] | 14—15 | 0 |

Commemoration

There exists literature in Turkey dealing with these events, but outside of Turkey, the events are largely unknown to the world public.

Impact on Europe

According to Mark Levene, the Victorian public in the 1870s paid much more attention to the massacres and expulsions of Christians than to massacres and expulsions of Muslims, even if on a greater scale. He further suggests that such massacres were even favored by some circles. Mark Levene also argues that the dominant powers, by supporting "nation-statism" at the Congress of Berlin, legitimized "the primary instrument of Balkan nation-building": ethnic cleansing.[104]

Memorials

There is a monument in Iğdır, Turkey, called Iğdır Genocide Memorial and Museum, remembering the Muslim victims of World War I.

A monument was erected in Anaklia, Georgia on 21 May 2012, to commemorate the expulsion of the Circassians.[105]

Gallery

.jpg) A Cretan Muslim family sent to Turkey after the population exchange in 1923.

A Cretan Muslim family sent to Turkey after the population exchange in 1923. A mass grave excavation in the town of Yeşilyayla, Erzurum.

A mass grave excavation in the town of Yeşilyayla, Erzurum.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Religious persecution. |

- Persecution of Muslims

- Ottoman persecution of Alevis

- Ottoman casualties of World War I

- Hamidian massacres

- Armenian Genocide

- Assyrian Genocide

- Greek Genocide

- Circassian Genocide

References

- McCarthy, Justin Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821–1922, Darwin Press Incorporated, 1996, ISBN 0-87850-094-4, Chapter one, The land to be lost, p. 1

- Norman Itzkowitz, Ottoman Empire and Islamic Tradition. University of Chicago Press, 2008, ISBN 9780226098012, p. 12

- Conversion to Islam in the Balkans: Kisve Bahas ̧petitions and Ottoman Social Life, 1670–1730, Anton Minkov, BRILL, 2004, ISBN 9004135766.

- The Geography of the Middle East, Stephen Hemsley Longrigg, James P. Jankowski, Transaction Publishers, 2009, ISBN 0202362965, p. 113.

- Hall, Richard C. (2002), The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: prelude to the First World War, Routledge, pp. 136–137

- Malik, Maleiha (13 September 2013). ANTI-MUSLIM PREJUDICE – MALIK: Past and Present. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-317-98898-4.

Christian irregulars in the Austrian or Venetian service, and insurgent highlanders of Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania meanwhile threw off 'the Turkish yoke' by marauding, mostly against the Muslim Slavs.

- Mitzen, Jennifer (10 September 2013). Power in Concert: The Nineteenth-Century Origins of Global Governance. University of Chicago Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-226-06025-5.

Peter the Great called on Balkan subjects to revolt in 1711; Catherine the Great encouraged a Greek rebellion in 1770 and

- Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Egdunas Racius (19 September 2013). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. BRILL. p. 165. ISBN 978-90-04-25586-9.

According to reliable estimates, during the 16th century around one fourth of the population in Slavonia,..., were Muslims, living mostly in towns.

- Wilson, Peter (1 November 2002). German Armies: War and German Society, 1648–1806. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-135-37053-4.

By 1699 130,000 Slavonian and Croatian Muslims had been driven to Ottoman Bosnia by the advancing imperialists.

- Velikonja, Mitja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

...in Hungary, Croatia, Dalmatia, Slavonia, and Lika after the Habsburg-Ottoman war of 1683–99. It was the first example in this area of cleansing the Muslim population that also "enjoyed the benediction of Catholic church".

- Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Egdunas Racius (19 September 2013). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. BRILL. p. 166. ISBN 978-90-04-25586-9.

All Muslim population left these areas or was expelled, killed or enslaved

- Malik, Maleiha (13 September 2013). ANTI-MUSLIM PREJUDICE – MALIK: Past and Present. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-317-98898-4.

Leopold I...not consider extending any privileges to the Muslims. They therefore fled to Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia and further southeast, fanning anti-Christian sentiments among their coreligionists.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1 January 2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. p. 466. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2.

... a period during which relations between the Muslim and non-Muslim populations of the region deteriorated sharply

- Velikonja, Mitja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

The entire Slavonian Muslim population fled south into Bosnia after the Treaty of Karlovac in 1699.

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9781557535948.

Many more Muslim families that had lived in Slavonia moved to Posavina after 1699 and during the first two decades of the eighteenth

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9781557535948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Velikonja, Mitja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

As in all other reconquered territories, the Muslims (who for example comprised two-thirds of the population in Lika) in Croatia were either converted to Catholicism or banished.

- Mohorovičić, Andro (1994). Architecture in Croatia: Architecture and Town Planning. Croatian Academy of Science and Arts. p. 114. ISBN 978-953-0-31657-7.

With the Turks gone, almost all the Turkish buildings on Croatian area were destroyed.

- al-Arnaut, Muhamed Mufaku (1994). "Islam and Muslims in Bosnia 1878–1918: Two Hijras and Two Fatwās". Journal of Islamic Studies. 5. (2): 245–246. "This being the case, the Muslim Bosnians could no longer imagine any existence for Muslims outside the devlet unless they lived outside the pale of the din, it cannot be denied that the attitude of neighbouring countries had influenced this state of mind. For after two centuries of stability and supremacy dār ar-Islām was no longer immune from attack. Muslims now faced a new, unexpected, inconceivable situation. The triumph of their Christian enemies meant that, in order to survive, the Muslims had to choose either to Christianize and remain inside the Christian state or to emigrate southwards in order to remain Muslims within the Muslim state. Thus we notice that Austria in particular, when changing from the defensive to the offensive, was concentrating on Bosnia, but without its Muslims. in the war of 1737–9 we find Emperor Charles VI, in the edict addressed to the Muslim Bosnians dated June 1737, outlining two options for them: 'whoever of them wishes to adopt Christianity, may be free to stay and retain his property, while those who do not may emigrate to wherever they want' They fared no better in the 1788–91 war, although Emperor Joseph I issued a proclamation in which he promised to respect Muslim rights and institutions. However, despite these pledges, the Muslims quickly disappeared from the areas ceded by the Ottoman Empire."

- Black, Jeremy (12 February 2007). European Warfare in a Global Context, 1660–1815. Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-134-15922-2.

The Muslim population of Montenegro was massacred by the Serbs.

- Király, Béla K.; Rothenberg, Gunther Erich (1982). War and Society in East Central Europe: East Central European Society and War in the Pre-Revolutionary Eighteenth Century. Brooklyn College Press : distributed by Columbia University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-930888-19-0.

Even the precise date of the bloody affair is not certain, but most historians have accepted 1709 as the year of the assault

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 615. ISBN 9780313309847.

- Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 466. "Extant class hatred of the Serbian peasants towards urban Muslim merchants and land owners was clearly a major motivator for mass violence. Nenadović describes the take-over of Valjevo by the rebels: At that time... there were twenty-four mosques and it was said that there were nearly three thousand Turkish and some two hundred Christian houses.... Any house that had not been burnt, the Serbs tore to bits and took their windows and doors and everything else that could be removed."

- Palairet, Michael R (2003). The Balkan economies c. 1800–1914: evolution without development. Cambridge University Press. p. 28-29. " As the characteristically high urbanization of Ottoman Europe reflected institutional structure rather than economic complexity, the dissolution of Ottoman institutions by the successor states could cause rapid deurbanization. This process occurred in its most striking form in Serbia. In the eighteenth century, Ottoman Serbia was highly urbanized, but during the wars and the revolutionary upheaval of 1789—1815, the Serbian towns experienced a precipitous decline. In 1777, there were reportedly some 6,000 houses in Belgrade," from which a population of 30,000 — 55,000 may be estimated. By about 1800, the town had shrunk to around 3,000 houses with 25,000 inhabitants, and in 1834 the number of houses had fallen further to 769. Late-eighteenth-century Užice had 2,900 Muslim houses; this indicates a population of around 20,000, for when the last 3,834 Muslims were driven from the town in 1862, they vacated 550 houses. Tihomir Dordević put the population of Užice in the late eighteenth century still higher, at 12,000 houses with about 60,000 inhabitants. By 1860, when Užice's population was 4,100, but still overwhelmingly Muslim, the effects of the town's decline were all too visible, the bazaars 'rotting and ruinous', and 'whole streets which stood here before the Servian revolution... turned into orchards'. In 1863, after the expulsions, there remained in the town a population of some 2,490. Valjevo in the 1770s was also a substantial place with 3,000 Muslim and 200 Christian houses. At least 5 other towns had 200 — 500 houses each. Given the low population density of Ottoman Serbia, a remarkably high proportion of its inhabitants were town dwellers. Belgrade pašaluk in the late eighteenth century had 376,000 Serbian and 40,000 — 50,000 Turkish inhabitants. On this basis, the two largest towns alone would have accounted for 11—27 per cent of the population of the pašaluk. The urban proportion could have been higher still, for a number of smaller towns dwindled into villages on the departure of the Ottomans.

- Pekesen, Berna (2012). Expulsion and Emigration of the Muslims from the Balkans. Leibniz Institute of European History.

- Pinson, Mark (1996). The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Their Historic Development from the Middle Ages to the Dissolution of Yugoslavia. Harvard CMES. p. 73. ISBN 9780932885128.

- Grandits, Hannes (2011). Conflicting Loyalties in the Balkans: The Great Powers, the Ottoman Empire and Nation-Building. I.B.Tauris. p. 208. ISBN 9781848854772.

- Zulfikarpašić, Adil (1998). The Bosniak. Hurst. p. 23-24. "In accordance with this principle Serbia had been cleansed of Muslims, and even of those Serbs who had converted to Islam and who lived around Užice and Valjevo. In negotiations between Turkey and Serbia they had been declared Turks and forced to move, and so they had resettled in Bosnia. There are still hundreds of families in Tuzla, Šamac, Sarajevo and Foča who are descendants of these immigrants from Užice — Serbian speaking Muslims. This was all a repeat of what had happened a few centuries before in Slavonia and Lika. The region of Lika, for example, was 65 per cent Muslim land until it fell into Austrian hands, when the Muslims were given the choice between expulsion and conversion."

- Fredborg, Arvid (2012). Serber och kroater i historien. Atlantis. p. 54. ISBN 9789173535625.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 4, 6, 31, 34, 155–156. ISBN 9781442230385.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1999), History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, pp.347

- Arthur Howard, Douglas (2001). The History of Turkey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 67. ISBN 9780313307089.

- Poulton, Hugh (1997). Muslim Identity and the Balkan State. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9781850652762.

- Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. 2 (2): para. 4, 9, 32–42, 45–61.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 4, 9, 32–42, 45–61.

- Luković, Miloš (2011). "Development of the Modern Serbian state and abolishment of Ottoman Agrarian relations in the 19th century" " Český lid. 98. (3): 298. "During the second war (December 1877 — January 1878) the Muslim population fled towns (Vranya (Vranje), Leskovac, Ürgüp (Prokuplje), Niş (Niš), Şehirköy (Pirot), etc.) as well as rural settlements where they comprised ethnically compact communities (certain parts of Toplica, Jablanica, Pusta Reka, Masurica and other regions in the South Morava River basin). At the end of the war these Muslim refugees ended up in the region of Kosovo and Metohija, in the territory of the Ottoman Empire, following the demarcation of the new border with the Principality of Serbia. [38] [38] On Muslim refugees (muhaciri) from the regions of southeast Serbia, who relocated in Macedonia and Kosovo, see Trifunovski 1978, Radovanovič 2000."

- Jagodić 1998, para. 4, 5, 6.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 11.

- Popovic, Alexandre (1991). The Cherkess on Yugoslav Territory (A Supplement to the article "Cherkess" in the Encyclopaedia of Islam). Central Asian Survey. pp. 68, 73.

- McCarthy, Justin (2000). "Muslims in Ottoman Europe: Population from 1800–1912". Nationalities Papers. 28. (1): 35.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p. 228. ISBN 9780810874831.

- Sabit Uka (2004). Dëbimi i Shqiptarëve nga Sanxhaku i Nishit dhe vendosja e tyre në Kosovë:(1877/1878-1912)[The expulsion of the Albanians from Sanjak of Nish and their resettlement in Kosovo: (1877/1878-1912)]. Verana. pp. 26–29.

- Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) [The reasons for the manner of the exodus of Albanian refugees from the territory of the Sanjak of Nish to Kosovo (1878–1878)] ". Studia Albanica. 1: 189–190.

- Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) [Nine English documents about the League of Prizren (1878–1880)]". Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike). 10: 198.

- Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). Rumeli'den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans [Turkish emigrations from the Balkans]. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.

- Bataković, Dušan (1992). The Kosovo Chronicles. Plato.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Scarecrow Press. p. XXXII. ISBN 9780333666128.

- Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 470.

- Müller, Dietmar (2009). "Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941." East Central Europe. 36. (1): 70. "For Serbia the war of 1878, where the Serbians fought side by side with Russian and Romanian troops against the Ottoman Empire, and the Berlin Congress were of central importance, as in the Romanian case. The beginning of a new quality of the Serbian-Albanian history of conflict was marked by the expulsion of Albanian Muslims from Niš Sandžak which was part and parcel of the fighting (Clewing 2000 : 45ff.; Jagodić 1998 ; Pllana 1985). Driving out the Albanians from the annexed territory, now called "New Serbia," was a result of collaboration between regular troops and guerrilla forces, and it was done in a manner which can be characterized as ethnic cleansing, since the victims were not only the combatants, but also virtually any civilian regardless of their attitude towards the Serbians (Müller 2005b). The majority of the refugees settled in neighboring Kosovo where they shed their bitter feelings on the local Serbs and ousted some of them from merchant positions, thereby enlarging the area of Serbian-Albanian conflict and intensifying it."

- Jagodić 1998, para. 3, 17.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 17.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 17–26.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 18–20.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 18–20, 25.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 25.

- Turović, Dobrosav (2002). Gornja Jablanica, Kroz istoriju. Beograd Zavičajno udruženje. pp. 87–89.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 29.

- Sabit Uka (2004). Dëbimi i Shqiptarëve nga Sanxhaku i Nishit dhe vendosja e tyre në Kosovë:(1877/1878-1912)[The expulsion of the Albanians from Sanjak of Nish and their resettlement in Kosovo: (1877/1878-1912)]. Verana. pp. 194–286.

- Osmani, Jusuf (2000). Kolonizimi Serb i Kosovës Archived 26 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine [Serbian colonization of Kosovo]. Era. pp. 48–50.

- Osmani. Kolonizimi Serb. 2000. p. 43-64.

- Frantz, Eva Anne (2009). "Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation." Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29. (4) : 460–461. "In consequence of the Russian-Ottoman war, a violent expulsion of nearly the entire Muslim, predominantly Albanian-speaking, population was carried out in the sanjak of Niš and Toplica during the winter of 1877—1878 by the Serbian troops. This was one major factor encouraging further violence, but also contributing greatly to the formation of the League of Prizren. The league was created in an opposing reaction to the Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin and is generally regarded as the beginning of the Albanian national movement. The displaced persons (Alb. muhaxhirë, Turk. muhacir, Serb. muhadžir) took refuge predominantly in the eastern parts of Kosovo. The Austro-Hungarian consul Jelinek reported in April 1878.... The account shows that these displaced persons (muhaxhirë) were highly hostile to the local Slav population. But also the Albanian peasant population did not welcome the refugees, since they constituted a factor of economic rivalry. As a consequence of these expulsions, the interreligious and interethnic relations worsened. Violent acts of Muslims against Christians, in the first place against Orthodox but also against Catholics, accelerated. This can he explained by the fears of the Muslim population in Kosovo that were stimulated by expulsions of large Muslim population groups in other parts of the Balkans in consequence of the wars in the nineteenth century in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated and new Balkan states were founded. The latter pursued a policy of ethnic homogenisation expelling large Muslim population groups."

- Stefanović. Seeing the Albanians. 2005. p. 470. "The 'cleansing' of Toplica and Kosanica would have long-term negative effects on Serbian-Albanian relations. The Albanians expelled from these regions moved over the new border to Kosovo, where the Ottoman authorities forced the Serb population out of the border region and settled the refugees there. Janjićije Popović, a Kosovo Serb community leader in the period prior to the Balkan Wars, noted that after the 1876–8 wars, the hatred of the Turks and Albanians towards the Serbs 'tripled'. A number of Albanian refugees from Toplica region, radicalized by their experience, engaged in retaliatory violence against the Serbian minority in Kosovo. In 1900 Živojin Perić, a Belgrade Professor of Law, noted that in retrospect, 'this unbearable situation probably would not have occurred had the Serbian government allowed Albanians to stay in Serbia'. He also argued that conciliatory treatment towards Albanians in Serbia could have helped the Serbian government to gain the sympathies of Albanians of the Ottoman Empire. Thus, while both humanitarian concerns and Serbian political interests would have dictated conciliation and moderation, the Serbian government, motivated by exclusive nationalist and anti-Muslim sentiments, chose expulsion. The 1878 cleansing was a turning point because it was the first gross and large-scale injustice committed by Serbian forces against the Albanians. From that point onward, both ethnic groups had recent experiences of massive victimization that could be used to justify 'revenge' attacks. Furthermore, Muslim Albanians had every reason to resist the incorporation into the Serbian state."

- al-Arnaut, Muhamed Mufaku (1994). "Islam and Muslims in Bosnia 1878–1918: Two Hijras and Two Fatwās". Journal of Islamic Studies. 5. (2): 246–247. "As for Bosnia, the treaty signed at the congress of Berlin in 1878 stunned the Muslims of that country who did not believe that the Ottoman Empire would forsake them so easily, and did not docilely resign themselves to the new Austro-Hungarian rule. They set up a government for their own defence and fiercely resisted the Austro-Hungarian forces for about three months (29 July-20 October 1878), a period which witnessed nearly sixty military clashes and resulted in 5000 casualties either killed or wounded." It may be noted that this stiff resistance was carried out almost exclusively by the Muslims, who were in this instance defending the homeland or vatan (Bosnia) and not the devlet (the Ottoman Empire) which forsook them. The Ottoman government had indeed seen in this resistance an opportunity to improve its own position and scored several points in its favour at the Istanbul Convention of 21 April 1879. For example, it was emphasized that the fact of occupation constituted no infringement of the' sovereign rights of the sultan over Bosnia, that the Muslims had the right to maintain their ties with Istanbul, that the name of the sultan could be mentioned in the Friday prayer sermon and on similar occasions, and that the Ottoman flag could be raised on the mosques." But this new situation created such a nightmare that some elderly men preferred to confine themselves to their homes rather than see 'infidels' in the streets. The Muslims, who had not yet recovered from the 1878 shock, were taken aback by the new military service law of 1881 which applied to Muslim youths also. This increased dissatisfaction with the new situation and speeded up hijra to the Ottoman Empire."

- Kaser, Karl (2011). The Balkans and the Near East: Introduction to a Shared History. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 336. ISBN 9783643501905.

- al-Arnaut. Islam and Muslims in Bosnia 1878–1918. 1994. p. 243. "As regards Bosnia, we have a hijra that deserves close attention, namely that which took place during the time of Ausrro-Hungarian rule (1878–1918) and evicted about 150,000 Muslims from Bosnia.[5] There are considerable differences in the estimates of the numbers of Bosnians emigrating to the Ottoman Empire during the period of Austro-Hungarian rule (1878–1915). The official statistics of the Austro-Hungarian administration admit that 61,000 Muslims emigrated, while Bogičević gives 150,000, Smlatić gives 160,000, and Imamović's estimate ranges between 150.000 and 180,000. Newspaper estimates rise to 300,000 and popular accounts put a figure as high as 700,000. Official statistics no doubt reduced the number of emigrants to make them equal the number of settlers who stayed in Bosnia (63,376). If we look at Ottoman data, we will find a wide gap between them and the Austro-Hungarian data. The Istanbul High Commissioners Office for Facilitating Refugee Settlement told Hiviz Bjelevac, the Bosnian writer, that during 1900–05 alone 73,000 Muslims left Bosnia, while Austro-Hungarian statistics give the much smaller number of 13,150. From all that has been said above, a figure like 150,000 will probably be more realistic. See Jovan Cvijić, 'o iseljavanju bosanskih muhamdanaca', Srpski književni glasnik XXIV, hr. 12, Beograd 16, VI, 1910, 966; Gaston Gravier, Emigracija Muslimana is BiH', Pregled, br. 7–8, Sarajevo 15. 1. 1911, 475; Vojslav Bogicević, Emigracija muslimana Bosnei Hercegovine u Tursku u doba austro-ugarske vladavine 1878–1918', Historijski zbornik 1–4, Zagreb 1958, 175–88; Mustafa Imamović, Pravni poloj i unutrašnjo-polički razvitak BiH od 1878–1914 (Sarajevo, 1976), 108–33; Dževat Juzbalić, Neke napomene o problemtici etničkog i društvenog razviska u Bosne i Hercegovine u periodu austro-ugarake uprave', Prilozi br. 11–12 (Sarajevo, 1976), 305; Iljaz Hadžibegovi, 'Iseljavanje iz Bosne i Hercegovine za vrijeme austro-ugarske uprave (1878 do 1918)', in Iseljaništvo naroda i narodnosti Jugoslavije (Zagreb, 1978), 246–7; Sulejman Smlatić, 'Iselavanje jugoslovenskih Muslinana u Tursku i njihovo prilagodjavanje novoj sredini', ibid. 253–3; Mustafa lmamović, 'Pregled istorije genocida nad Muslimanima u jugoslovenskim zemljama', Glasnik SIZ, hr. 6 (Sarajevo 1991), 683–5."

- Grossman, David (2011). Rural Arab Demography and Early Jewish Settlement in Palestine: Distribution and Population Density during the Late Ottoman and Early Mandate Periods. Transaction Publishers. p. 70.

- Cohen, Philip J. (1996). Serbia's secret war: propaganda and the deceit of history. Texas A&M University Press. p. 123.

- Ibrahim al-Marashi. "The Arab Bosnians?: The Middle East and the Security of the Balkans" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Incorporated, Facts On File (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. p. 244. ISBN 9781438126760.

- Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 291. ISBN 9780801885570.

- Neuburger, Mary (2004). The Orient Within: Muslim Minorities and the Negotiation of Nationhood in Modern Bulgaria. Cornell University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780801441325.

- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity. Princeton University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781400841844.

- Horne, John (2013). War in Peace. Oxford University Press. pp. 173–177. ISBN 9780199686056.

- Levene, Mark (2013). Devastation. Oxford University Press. pp. 217, 218. ISBN 9780191505546.

- J. Rummel, Rudolph (1998). Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 82, 83. ISBN 9783825840105.

- Kerr, Stanley Elphinstone (1973). The Lions of Marash. SUNY Press. p. 195. ISBN 9781438408828.

- Allied Commission, Atrocités Grecques en Turquie, 1921.

- Steven Béla Várdy; T. Hunt Tooley; Ágnes Huszár Várdy (2003). Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Social Science Monographs. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-88033-995-7.

- (Akçam 2006, p. 318)

- Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1970). The Western Question in Greece and Turkey:A Study in the Contact of Civilizations (The full version can be found here (Online reports of Arnold Toynbee)). H. Fertig, originally: University of California. pp. 283–284.

'The members of the Commission consider that, in the part of the kazas of Yalova and Guemlek occupied by the Greek army, there is a systematic plan of destruction of Turkish villages and extinction of the Moslem population. This plan is being carried out by Greek and Armenian bands, which appear to operate under Greek instructions and sometimes even with the assistance of detachments of regular troops

- Hofmann, Tessa (2016). "Yalova/Nicomedia 1920/1921. Massacres and Inter- Ethnic Conflict in a Failing State". The Displacement, Extinction and Genocide of the Pontic Greeks. 1916-1923: 8.

The British journalist and historian Arnold Joseph Toynbee, who was war correspondent for the "Manchester Guardian" on the Yalova Peninsula from April until 3 July 1921, suggests a total of 300 Muslim victims.

- "Arşiv Belgelerine Göre Balkanlar'da ve Anadolu'da Yunan Mezâlimi 2". Scribd.com. 3 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Gingeras, Ryan (2009). Sorrowful Shores:Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1912–1923. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780191609794.

In total only thirty-five were reported to have been killed, wounded, beaten, or missing. This is in line with the observations of Arnold Toynbee, who declared that one to two murders were sufficient to drive away the population of a village.

- McNeill, William H. (1989). Arnold J. Toynbee: A Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199923397.

To protect their flanks from harassment, Greek military authorities then encouraged irregular bands of armed men to attack and destroy Turkish populations of the region they proposed to abandon. By the time the Red Crescent vessel arrived at Yalova from Constantinople in the last week of May, fourteen out of sixteen villages in that town's immediate hinterland had been destroyed, and there were only 1500 survivors from the 7000 Moslems who had been living in these communities.

- Naimark 2002, p. 46.

- Chenoweth, Erica (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-state Actors in Conflict. MIT Press. pp. 48, 49. ISBN 9780262014205.

- Naimark 2002, p. 45.

- Hirschon, ed. by Renée (2003). Crossing the Aegean : an appraisal of the 1923 compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey (1. publ. ed.). New York, NY [u.a.]: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571817679.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Mann, Michael (2005). The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. ISBN 0521538548. "In the Balkans all statistics of death remain contested. Most of the following figures derive from McCarthy (1995: 1, 91, 161-4, 339), who is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate. Yet even if we reduced his figures by as much as 50 percent, they would still horrify. He estimates that between 1811 and 1912, somewhere around 5 1/2 million Muslims were driven out of Europe and million more were killed or died of disease or starvation while fleeing. Cleansing resulted from Serbian and Greek independence in the 1820s and 1830s, from Bulgarian independence in 1877, and from the Balkan wars culminating in 1912."

- Door Michael M. Gunter. Armenian History and the Question of Genocide. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, p. 127

- Door Natasha May Azarian. The Seeds of Memory: Narrative Renditions of the Armenian Genocide Across. ProQuest, 2007, p. 14: "...the leading Pro-Turkish academic"

- Bloxham. The Great Game of Genocide, p. 210. "Some of McCarthy's work considers the great population changes of the period, including extensive examination of the expulsion of Muslims from the new Balkan states and the overall demographic catastrophes of 1912–23... McCarthy's work has something to offer in drawing attention to the oft-unheeded history of Muslim suffering and embattlement that shaped the mindset of the perpetrators of 1915. It also shows that vicious ethnic nationalism was by no means the sole preserve of the CUP and its successors."

- Beachler, Donald W. (2011). The genocide debate: politicians, academics, and victims. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-230-33763-3. "Justin McCarthy has, along with other historians, provided a necessary corrective to much of the history produced by scholars of the Armenian genocide in the United States. McCarthy demonstrates that not all of the ethnic cleansing and ethnic killing in the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries followed the model often posited in the West, whereby all the victims were Christian and all the perpetrators were Muslim. McCarthy has shown that there were mass killings of Muslims and deportations of millions of Muslims from the Balkans and the Caucasus over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. McCarthy, who is labeled (correctly in this author's estimation) as being pro- Turkish by some writers and is a denier of the Armenian genocide, has estimated that about 5.5 million Muslims were killed in the hundred years from 1821–1922. Several million more refugees poured out of the Balkans and Russian conquered areas, forming a large refugee (muhajir) community in Istanbul and Anatolia."

- Biondich, Mark (2011). The Balkans: Revolution, War, and Political Violence Since 1878. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780199299058.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "In the period between 1878 and 1912, as many as two million Muslims emigrated voluntarily or involuntarily from the Balkans. When one adds those who were killed or expelled between 1912 and 1923, the number of Muslim casualties from the Balkan far exceeds three million. By 1923 fewer than one million remained in the Balkans."

- J. Gibney, Matthew (2005). Immigration and Asylum: From 1900 to the Present, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 437. ISBN 9781576077962.

- Owen, Roger (1998). A History of Middle East Economies in the Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780674398306.

- Tošić, Jelena (2015). "City of the 'calm': Vernacular mobility and genealogies of urbanity in a southeast European borderland". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 15 (3): 391–408. doi:10.1080/14683857.2015.1091182.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) pp.394-395. "Like the Ulqinak, the Podgoriçani thus personify the mass forced displacement of the Muslim population from the Balkans and the 'unmixing of peoples' (see e.g. Brubaker 1996, 153) at the time of the retreat of the Ottoman Empire, which has only recently sparked renewed scholarly interest" (e.g. Blumi 2013; Chatty 2013).

- Kiel, Machiel (1990). Studies on the Ottoman Architecture of the Balkans. University of Michigan. pp. XI, X, XIV, XV. ISBN 9780860782766.

- Meskell, Lynn (2001). Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Routledge. pp. 121, 122. ISBN 9781134643905.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 22. ISBN 9781442206632.

- Prica, Radomir (1969). Sremska Mitrovica. Skupština opštine; Muzej Srema.

...наводно са 17 џамија...

- Lang, Antun; Kupinski, Ivan (1970). Slavonija 70 [i.e. sedanideset]. Ekonomski institut. p. 65.

U njemu je živjelo pretežno muslimansko stanovništvo za koje je podignuto sedam džamija, te je grad dobio orijentalno obilježje.

- scrinia slavonica 12 (2012), 21–26. 21. Nedim Zahirović "U gradu Požegi postojalo je osamdesetih godina 16. stoljeća 10–11 islamskih bogomolja, a 1666. godine 14–15"

- Levene, Mark (2005), "Genocide in the Age of the Nation State" pp. 225–226

- "Georgian Diaspora – Calendar".

Sources

- Stanford J. Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Cambridge University Press, 1977, ISBN 9780521291668

- Alan W. Fisher, The Crimean Tatars, Hoover Press, 1978, ISBN 9780817966638

- Walter Richmond, The Circassian Genocide, Rutgers University Press, 2013, ISBN 9780813560694

- Alexander Laban Hinton, Thomas La Pointe,Hidden Genocides, Douglas Irvin-Erickson, Rutgers University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0813561646

- Erica Chenoweth, Adria Lawrence,Rethinking Violence, MIT Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0262014205

- Klejda Mulaj, Politics of Ethnic Cleansing, Lexington Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0739146675

- John K. Cox, The History of Serbia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 978-0313312908

- Igor Despot, The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of the Warring Parties, iUniverse, 2012, ISBN 978-1475947052

- Douglas Arthur Howard, The History of Turkey, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 978-0313307089

- Benjamin Lieberman, Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, 2013, ISBN 978-1442230385

- John Joseph, Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries, SUNY Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0873956000

- Victor Roudometof, Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 978-0313319495

- Charles Jelavich, The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920, University of Washington Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0295803609

- Suraiya Faroqhi, The Cambridge History of Turkey, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0521620956

- Ryan Gingeras, Sorrowful Shores, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0191609794

- Ugur Ümit Üngör, The Making of Modern Turkey, Oxford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0191640766

- Stanley Elphinstone Kerr, The Lions of Marash, SUNY Press, 1973, ISBN 978-1438408828