Fifth Air Force

The Fifth Air Force (5 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Japan. It is the U.S. Air Force's oldest continuously serving Numbered Air Force. The organization has provided 70 years of continuous air power to the Pacific since its establishment in September 1941.[3]

| Fifth Air Force | |

|---|---|

Shield of the Fifth Air Force | |

| Active | 5 February 1942 - present (as Fifth Air Force) 5 February 1942 - 18 September 1942 (as 5 Air Force) 28 October 1941 - 5 February 1942 (Far Eastern Air Force) 16 August 1941 - 28 October 1941 (as Philippine Department Air Force) (78 years, 10 months)[1] |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Numbered Air Force |

| Role | Provide combat-ready air forces for U.S. Pacific Command and U.S. Forces Japan, along with serving as the air component for U.S. Forces Japan[2] |

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Yokota Air Base, Tokyo Metropolis, Japan |

| Engagements | See list

|

| Decorations | See list

|

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | LtGen Kevin B. Schneider |

| Notable commanders | George Kenney Earle E. Partridge Samuel E. Anderson Richard Myers |

Fifth Air Force is the Headquarters Pacific Air Forces forward element in Japan, and maximizes partnership capabilities and promotes bilateral defense cooperation. In addition, 5 AF is the air component to United States Forces Japan.[3]

Its mission is three-fold. First, it plans, conducts, controls, and coordinates air operations assigned by the PACAF Commander. Fifth Air Force maintains a level of readiness necessary for successful completion of directed military operations. And last, but certainly not least, Fifth Air Force assists in the mutual defense of Japan and enhances regional stability by planning, exercising, and executing joint air operations in partnership with Japan. To achieve this mission, Fifth Air Force maintains its deterrent force posture to protect both U.S. and Japanese interests, and conducts appropriate air operations should deterrence fail.[3]

Fifth Air Force is commanded by Lieutenant General Kevin B. Schneider.

History

To reflect the expanded scope of the defensive forces the United States was sending to the Philippines, the Philippine Department Air Force was re-designated as Far East Air Force on 16 November 1941 with the Philippine Army Air Corps being incorporated as part of the new organization.[4]

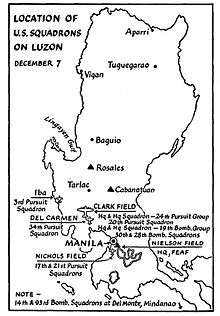

The mission of Far East Air Force on 7 December 1941 was air defense of the Philippine Islands. Its commander was Major General Lewis H. Brereton. Its order of battle was as follows:[5]

5th Bomber Command

- 19th Bombardment Group, Clark Field (B-17D/E Flying Fortress, 35 Aircraft)

- 14th Bombardment Squadron Del Monte Airfield, Mindanao

- 28th Bombardment Squadron

- 30th Bombardment Squadron

- 32d Bombardment Squadron

- Ground echelon en route from US to Philippine Islands via ship, air echelon at Hamilton Field, California

- 38th Reconnaissance Squadron

- Ground echelon en route from US to Philippine Islands via ship, air echelon en route from US to Hawaii, destroyed in Pearl Harbor Attack.

- 93d Bombardment Squadron Del Monte Airfield, Mindanao

- A light bombardment group, the 27th Bombardment Group (Light), ground echelon had arrived at Fort William McKinley, however the A-24 Banshee dive bombers had not yet arrived from the United States. They were diverted to Brisbane, Australia after the Japanese Invasion on 8 December 1941 and were not used in the ensuing Battle of the Philippines. The ground echelon was assigned as Army Air Corps ground forces as 27th Bombardment Group Provisional Infantry Regiment (Air Corps)

- A second B-17 group, the 7th Bombardment Group with four squadrons of aircraft, had not arrived by the time war broke out on 8 December. It was diverted to Archerfield Airport, Brisbane, Australia, on 22 December 1941 due to the deteriorating situation in the Philippines.

5th Interceptor Command (Hq Nielson Field) provided RADAR defense of Luzon.[4]

- Iba Airfield had the only working SCR-271 air defense radar site in the Philippines. A second SCR-271 radar set may have been installed outside of Manila at Nielson Field, but that is unconfirmed. A third SCR-271 set was en route to the northwest tip of Luzon, about 60 miles from Aparri and a SCR-270 mobile radar set was on its way to site south of Manila when it got stuck in a swamp and its crew had to destroy it. The radars had a maximum search range of 110 mi (180 km) for aircraft flying as high as 25,000 ft (7,600 m). Actual detection distances ranged between 50 and 100 miles; with altitudes from 5,000 to 20,000 feet. Due to issues with the Philippine telephone system, reliable communications between Iba Field and headquarters at Nichols Field were unreliable, and radio communications between the radar site and headquarters was at best, uncertain.[6]

- 24th Pursuit Group, HQ, Clark Field (P-25, P-35, P-40, 81 aircraft)

- 3d Pursuit Squadron, Iba Field (P-40E)

- 17th Pursuit Squadron, Nichols Field (P-40E)

- 20th Pursuit Squadron, Clark Field, (P-40B)

- 21st Pursuit Squadron, Nichols Field (P-40E)

- 34th Pursuit Squadron, Del Carmen Field (P-35A)

- 6th Pursuit Squadron, (Philippine Army Air Corps) Batangas Field (P-26)

- 2d Observation Squadron, Nichols Field (O-46, O-52)

World War II

The first indications of war between the Japanese Empire and the United States began on the night of 2 December 1941 when a single plane flew over Clark Field on four consecutive nights. It came about 05:00 in the morning, but no origin for its flight could be found at any Luzon airfield. After its second appearance, orders were given to force the plane to land and, if the pilot committed any overt act, to shoot him down. A six-ship flight from the 17th Pursuit Squadron, was therefore ordered to attempt interception on the night of 4–5 December; but their search mission was unsuccessful, largely due to the lack of air-ground communication. The radios in their P-40s were ineffective beyond a maximum range of 20 miles. The 20th Pursuit Squadron also made an unsuccessful attempt to intercept on the night of 5–6 December. Though, on the night of 6–7 December, all aircraft were grounded except the 3d Pursuit Squadron; and the antiaircraft at Clark Field were alerted to shoot the plane down that night, however, the plane did not come.[6]

When the newly installed radar at Iba Airfield which first picked up the tracks of unidentified planes off the Zambales coast on 3 December and Clark Field reported its lone plane overflight for the second successive night Colonel George, now Chief of Staff of the 5th Interceptor Command, had gone to Far East Air Force headquarters at Nielson Field immediately to report not only the presence of the planes but his belief that the two flights were co-operating with each other and were the immediate preliminary to Japanese attack. Yet he had great difficulty in persuading some higher officers that these tracks represented hostile aircraft and not merely some unidentified private or commercial planes.[6]

At this time the decision was reached to send all the B-17s to Del Monte Field on Mindanao to get them out of range of direct attack by Japanese land-based planes on Formosa. If war came, the B-17s could themselves stage out of Clark Field, picking up their bombs and gasoline for the run to Formosa. But at FEAF Headquarters the latest information was that the 7th Bombardment Group, which was scheduled to deploy to FEAF, could be expected at any time with four full B-17 squadrons. Their plans called for basing the 7th Bomb Group at Del Monte Field as soon as it arrived, and, since the field there could accommodate at most six squadrons; only two of the 19th Group's squadrons at Clark were dispatched. All planes were to have cleared the field by midnight of the 5th. They began taking off singly beginning at 22:00 and it was nearly three hours before they completed their formation and headed south.[6]

At lba Field, the men watching the radar scope saw more incoming tracks on the screen. Outside on the blacked-out field the 3d Squadron's new P-40s stood on the line. However, the Japanese aircraft did not come in all the way; they stayed offshore, as though there were a point in time for them to meet before they turned hack. Then at the end of the runway one of the P-40s took off alone. The pilot made a long search but could not find them.[6]

Initial Japanese attacks on Far East Air Force (8–10 December 1941)

War did not come to the Philippines on 7 December, as it did to Pearl Harbor. Due to the International Date Line, Sunday, 7 December, remained a day of grace. The war between Imperial Japan and the United States, instead, began in Hawaii, by which time it was 8 December in the Philippines.[6][7]

About 4:30 am on 8 December the first fragmentary news of the Attack on Pearl Harbor was received in Manila. There had been an even earlier flash, caught about 3:30 by the commercial radio station at Clark Field, but as no verification had come through, no action was then taken beyond notifying the base commander. The Navy, however, had had the news since 3:00 am and most of their installations were alerted by 3:30. A radio operator had picked up a message in the clear, in Morse Code. It was twice repeated, and he recognized the sending technique of the operator at Pearl Harbor. This message was sent to Admiral Hart and to General MacArthur's Headquarters. Apparently it reached General MacArthur at about 4:00 am and within a few minutes Air Headquarters also had been notified. Official confirmation did not come through, at least to the 24th Pursuit Group, till about 4:45. At 5:30 am General Headquarters issued an official statement that Pearl Harbor had been heavily attacked by Japanese submarines and planes and that a state of war existed between the United States and the Empire of Japan.[6]

Combat was already beginning to break out in the Philippines. Japanese planes attacked a Philippine radio station at Aparri, on the north coast of Luzon. And just at dawn a line of Japanese dive bombers, heading in from the Pacific, caught two of the Navy's PBYs sitting on the water of Davao Gulf and sank them out of hand. Only by adroit maneuvering did the tender William B. Preston succeed in dodging the bombs and later evade four Japanese destroyers entering the gulf in obvious search of her. At about 08:00 while one shift of the flight crews were eating breakfast, the 17th Pursuit Squadron received orders to cover Clark Field, as a heavy fleet of Japanese bombers were reported north of Luzon heading down Lingayen Gulf towards the central plain. At Clark Field itself the B-17s were taking the air as a precautionary move in case the Japanese bombers broke through the fighter patrol lines.[6]

FEAF commander General Brereton sought permission from theater commander General Douglas MacArthur to conduct air raids against Japanese forces in Formosa, but was refused. It was a little before 08:00 when Brereton returned to Air Headquarters at Nielson Field. As he entered his office he asked what decision the staff had reached, but on being told said, "No, We can't attack till we're fired on" and explained that he had been directed to prepare the B-17s for action but was not to undertake offensive action till ordered. However, a photo-reconnaissance mission was authorized over Formosa which was requested either by Brereton or Sutherland. Later, about 1100 on 8 December a combat strike was approved by FEAF against Formosa, to take place that day, and the B-17s which were sent to Del Monte Field were recalled to Clark to stage for the strike. The B-17s were back a Clark Field after 11:30 and that MacArthur planned an attack against Formosa for the morning of 9 December.[6][7]

Initially, an air attack on the radar site at Iba Field by Japanese planes took place about 11:00 am. By that time, all but one of the B-17's was lined up on the line at Clark and the fighters were just getting ready to take off. However, after the warning of the Pearl Harbor attack, and after the loss of several valuable hours because of bad weather over Formosa, the Japanese pilots did not expect to find so rich a harvest of American aircraft on the ground at Clark Field. But they did not question their good fortune. The first flight of Japanese planes consisted of twenty-seven twin-engine bombers. They came over the unprotected field in a V-formation at a height estimated at 22,000 to 25,000 feet, dropping their bombs on the aircraft and buildings below, just as the air raid warning sounded. As at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese achieved complete tactical surprise.[6][7]

The first flight was followed immediately by a similar formation which remained over the field for fifteen minutes. The planes in this formation, as in the first, accomplished their mission almost entirely without molestation. American antiaircraft shells exploded from 2,000 to 4,000 feet short of the targets. After the second formation of bombers, came thirty-four Zeros- which the Americans believed were carrier based-to deliver the final blow with their low-level strafing attacks on the grounded B-17's, and on the P-40's with their full gasoline tanks. This attack lasted for more than an hour.[6][7]

Before dawn of the 9th seven Japanese naval bombers struck Nichols Field. Naval planes took off about 10:00 on 10 December to strike Luzon again. First warning of the approach of Japanese planes reached 5th Interceptor Command at Nielson Field at 11:15, and American fighters were immediately dispatched to cover Manila Bay. Japanese aircraft hit the Del Carmen Field near Clark, and the Nichols and Nielson Fields, near Manila. American planes returning to refuel were attacked by Zeros and destroyed. There was no antiaircraft fire and no fighter protection over the field; all the pursuit planes were engaged over Manila Bay.[6][7]

Battle of the Philippines (1941–42)

After three days of combat, FEAF was largely destroyed on the ground by Japanese air attacks from Formosa. The few remaining aircraft flew until the fall of Bataan, but accomplished little.[6]

- After being alerted of the Japanese attack on Hawaii, the B-17s of the 19th Bombardment Group at Clark Field were ordered into the air on the morning of 8 December while FEAF commander Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton sought approval to attack Japanese airfields on Formosa (Taiwan) in accordance with pre-war war plans. After two hours, Brereton received approval to carry out a late afternoon strike and recalled the B-17s to Clark to refuel and load bombs. P-40s on patrol over Luzon ran short of fuel and also landed shortly before noon local time. Of the 19 bombers based at Clark, one was in the air on a reconnaissance flight and another took off to flight test a newly repaired generator. A 20th B-17 was nearing Clark, having been sent up from Mindanao to repair a wing fuel tank. Three squadrons of P-40s took off just before noon to continue patrols but none were assigned the area of Clark Field. Radar and observers detected a large force of Japanese aircraft, delayed several hours on their bombing mission by fog over their bases, but poor communications and other errors failed to alert Clark of their approach. 108 Japanese naval bombers in two formations struck the field shortly after 12:30, destroying all but four P-40s on the field preparing to take off, and causing immense destruction to facilities. A wave of 80 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters arrived shortly after, and unopposed, strafed the base for 45 minutes, destroying all but five of 17 B-17s caught on the ground, and damaging three of the others so that they did not fly again. Within a week, only 14 of the original 35 based in the Philippines remained operational, stationed at Del Monte Airfield on Mindanao, attempting to remain out of range of Japanese air attacks. Beginning on 17 December, the surviving B-17s, badly in need of maintenance, began evacuate to Batchelor Field near Darwin, Australia.

- The 27th Bombardment Group, less one squadron, arrived at Fort William McKinley by ship on 20 November; however all of its A-24 aircraft had not yet arrived by 6 December. To avoid capture or destruction, the ship carrying the crated planes was diverted to Australia when the Japanese isolated the Philippines. The personnel of the 27th were formed into the "2nd Provisional Infantry Regiment" on Bataan. The 27th Bomb Group became the only Air Force unit in history to fight as an infantry regiment, and were the only unit to be taken captive in whole. After surrendering, they were forced to endure the infamous Bataan Death March. Of the 880 or so Airmen who were taken, less than half survived captivity. The air echelon of the 27th Bomb Group eventually reformed in Australia in 1942 and fought in the Dutch East Indies and New Guinea campaigns.

- The 24th Pursuit Group flew its last interception on 10 December and made several small-scale attacks on Japanese landing forces, but ceased to exist as an operational air combat organization by 24 December 1941. Its personnel were also sent into Bataan as the "1st Provisional Infantry Regiment" as a reserve force to the Philippine Division. Although destroyed as a unit, the group remained on the list of active AAF units until the end of the war.

- The P-26s of the Philippine Army Air Corps' 6th Pursuit Squadron were mostly destroyed on the ground in the first Japanese attacks following Pearl Harbor, but two flown by Filipino pilots scored victories over Japanese airplanes. In 1942, in a desperate defense of their homeland, the few surviving P-26s which the Filipino 6th Pursuit Squadron still had at its disposal were completely overwhelmed by Japanese A6M Zero fighters.

- The 34th Pursuit Squadron, attached to the 24th Pursuit Group, received 35 Seversky P-35As when its P-40s failed to arrive before war broke out. On 8 December 1941, when the Japanese launched the first air attacks on the Philippines, the obsolescent fighters proved completely inadequate for the task of air defense, too lightly armed and lacking both cockpit armor and self-sealing fuel tanks. Most were shot down in combat or destroyed on the ground in the first days of combat. By 12 December there were only eight airworthy P-35As remained.

After the Japanese land invasion of the Philippines on 24 December 1941, the mission of Fifth Interceptor Command changed to provide ground defense of Luzon, with ground and air echelon personnel of unequipped Far East Air Force units on Luzon attached to fight as ground infantry units during the Battle of the Philippines (1941–42) after their aircraft were destroyed or evacuated to locations away from Luzon. Most members of the unit surrendered on 9 April 1942 after the Battle of Bataan. Some survivors escaped to Corregidor Island in Manila Bay, Philippine Islands and surrendered on 6 May 1942, ending all US organized resistance to the Japanese in the Philippines. Some survivors possibly fought afterwards on Luzon as unorganized resistance (May 1942 – January 1945).

Establishment of Fifth Air Force

.svg.png)

14 B-17 Flying Fortresses that survived the Battle of the Philippines left Mindanao for Darwin, Australia, between 17 and 20 December 1941, the only aircraft of the Far East Air Force to escape. After its evacuation from the Philippines on 24 December 1941, FEAF headquarters moved to Australia and was reorganized and redesignated 5 Air Force on 5 February 1942, with most of its combat aircraft based on fields on Java. It seemed at the time that the Japanese were advancing just about everywhere. The remaining heavy bombers of the 19th Bombardment Group, based at Malang on Java, flew missions against the Japanese in an attempt to stop their advance. They were joined in January and February, two or three at a time, by 37 B-17Es and 12 LB-30s of the 7th Bombardment Group. The small force of bombers, never numbering more than 20 operational at any time, could do little to prevent the invasion of the Netherlands East Indies, launching valiant but futile attacks against the masses of Japanese shipping, with six lost in combat, six in accidents, and 26 destroyed on the ground.

The 7th Bombardment Group was withdrawn to India in March 1942, leaving the 19th to carry on as the only B-17 Fortress-equipped group in the South Pacific. About this time it was decided that replacement B-17s would not be sent to the southwest Pacific, but be sent exclusively to the Eighth Air Force which was building up in England. By May, 5 Air Force's surviving personnel and aircraft were detached to other commands and the headquarters remained unmanned for several months, but elements played a small part in the Battle of the Coral Sea (7–8 May 1942) when the 435th Bomb Squadron of the 19th Bomb Group saw the Japanese fleet gathering in Rabaul area nearly two weeks before the battle actually took place. Because of the reconnaissance activity of the 435th Bomb Squadron, the US Navy was prepared to cope adequately with the situation. The squadron was commended by the US Navy for its valuable assistance not only for its excellent reconnaissance work but for the part played in the battle.

Headquarters Fifth Air Force was re-staffed at Brisbane, Australia on 18 September 1942 and placed under the command of Major General George Kenney. United States Army Air Forces units in Australia, including Fifth Air Force, were eventually reinforced and re-organised following their initial defeats in the Philippines and the East Indies. At the time that Kenney had arrived, Fifth Air Force was equipped with three fighter groups and five bombardment groups.

|

Fighter Groups:

|

Bomber Groups:

|

In addition, Fifth Air Force controlled two transport squadrons and one photographic squadron comprising 1,602 officers and 18,116 men.

Kenney was later appointed commander of Allied air forces in the South West Pacific Area, reporting directly to General Douglas MacArthur. Under Kenney's leadership, the Fifth Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force provided the aerial spearhead for MacArthur's island hopping campaign.

US Far East Air Forces

On 4 November 1942, the Fifth Air Force commenced sustained action against the Japanese in Papua New Guinea and was a key component of the New Guinea campaign (1942–1945). Fifth Air Force engaged the Japanese again in the Philippines campaign (1944–45) as well as in the Battle of Okinawa (1945).

Fifth Air Force along with Thirteenth Air Force in the Central Pacific and Seventh Air Force in Hawaii were assigned to the newly created United States Far East Air Forces (FEAF) on 3 August 1944. FEAF was subordinate to the U.S. Army Forces Far East and served as the headquarters of Allied Air Forces Southwest Pacific Area. By 1945, the three numbered air forces were supporting operations throughout the Pacific. FEAF was the functional equivalent in the Pacific of the United States Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) in the European Theater of Operations.

Order of battle, 1945

| V Fighter Command | Night Fighter Units | V Bomber Command | Photo Reconnaissance | 54th Troop Carrier Wing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3d ACG (P-51, C-47) | 418th NFS | 3d BG (L) (B-25, A-20) | 6th RG (F-5, F-7) | 2d CCG |

| 8th FG (P-40, P-38) | 421st NFS | 22d BG (M/H) (B-26 – B-24) | 71st RG (B-25) | 317th TCG |

| 35th FG (P-47, P-51) | 547th NFS | 38th BG (M) (B-25) | 374th TCG (1943 only) | |

| 49th FG (P-40, P-47, P-38) | 43d BG (H) (B-24) | 375th TCG | ||

| 58th FG (P-47) | 90th BG (H) (B-24) | 433d TCG | ||

| 348th FG (P-47, P-51) | 312th BG (L) (A-20) | |||

| 475th FG (P-38) | 345th BG (M) (B-25) | |||

| 380th BG (H) (B-24) | ||||

| 417th BG (L) (A-20) | ||||

LEGEND: ACG – Air Commando Group, FG – Fighter Group, NFS – Night Fighter Squadron, BG (L) – Light Bomb Group, BG (M) – Medium Bomb Group, BG (H) – Heavy Bomb Group, RG – Reconnaissance Group, CCG – Combat Cargo Group, TCG – Troop Carrier Group

When the war ended, Fifth Air Force had an unmatched record of 3,445 aerial victories, led by the nation's two top fighter aces Major Richard Bong and Major Thomas McGuire, with 40 and 38 confirmed victories respectively, and two of Fifth Air Force's ten Medal of Honor recipients.

Shortly after World War II ended in August, Fifth Air Force relocated to Irumagawa Air Base, Japan, about 25 September 1945 as part of the Allied occupation forces. The command remained in Japan until 1 December 1950 performing occupation duties.

Korean War

for the units, stations and type aircraft flown in combat during the war (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953)

In 1950, Fifth Air Force was called upon again, becoming the main United Nations Command combat air command during the Korean War, and assisted in bringing about the Korean Armistice Agreement that formally ended the war in 1953.

In the early morning hours of 25 June, North Korea launched a sudden, all-out attack against the south. Reacting quickly to the invasion, Fifth Air Force units provided air cover over the skies of Seoul. The command transferred to Seoul on 1 December 1950, remaining in South Korea until 1 September 1954.

In this first Jet War, units assigned to the Fifth Air Force racked up an unprecedented 14.5 to 1 victory ratio. By the time the truce was signed in 1953, Fifth Air Force had flown over 625,000 missions, downing 953 North Korean and Chinese aircraft, while close air support accounted for 47 percent of all enemy troop casualties.

Thirty-eight fighter pilots were identified as aces, including Lieutenant Colonel James Jabara, America's first jet ace; and Captain Joseph McConnell, the leading Korean War ace with 16 confirmed victories. Additionally, four Medals of Honor were awarded to Fifth Air Force members. One other pilot of note was Marine Major John Glenn, who flew for Fifth Air Force as part of an exchange program.

With the end of combat in Korea, Fifth Air Force returned to normal peacetime readiness Japan in 1954.

Cold War

Not only concerned with maintaining a strong tactical posture for the defense of both Japan and South Korea, Fifth Air Force played a critical role in helping the establishment of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force as well as the Republic of Korea Air Force. These and other peacetime efforts lasted a decade before war clouds once again developed in the Pacific.

This time, the area of concern was Southeast Asia, beginning in 1964 with the Gulf of Tonkin Crisis. Fifth Air Force furnished aircraft, aircrews, Support personnel, and supplies throughout the eight years of combat operations in South Vietnam and Laos. Since 1972, the Pacific has seen relative calm, but that doesn't mean Fifth Air Force hasn't been active in other roles. The command has played active or supporting roles in a variety of issues ranging from being first on the scene at the Korean Air Lines Flight 007 shoot down in 1983 to deploying personnel and supplies for the Persian Gulf War in 1990.

During this time span, the size of Fifth Air Force changed as well. With the activation of Seventh Air Force in 1986, fifth left the Korean Peninsula and focused its energy on continuing the growing bilateral relationship with Japan.

The Fifth Air Force's efforts also go beyond combat operations. Fifth Air force has reacted to natural disasters in Japan and abroad. These efforts include the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995 and Super Typhoon Paka which hit Guam in 1997. Fifth Air Force has reached out to provide assistance to victims of floods, typhoons, volcanoes, and earthquakes throughout the region.

Present Day

Today, according to the organization's website, major components include the 18th Wing, Kadena Air Base, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan; the 35th Fighter Wing at Misawa Air Base, and the 374th Airlift Wing at Yokota Air Base.[3] Kadena AB hosts the 18th Wing, the largest combat wing in the USAF. The Wing includes F-15 fighters, KC-135 refuelers, E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft, and HH-60G Pave Hawk rescue helicopters, and represents a major combat presence and capability in the Western Pacific. The 35th Fighter Wing, Misawa Air Base, Japan, includes two squadrons equipped with the most modern Block 50 F-16 variant, dedicated to the suppression of enemy air defenses. The final formation is the 374th Airlift Wing, at Yokota Air Base, Japan.

According to a 2017 study by two US Navy commanders, in case of a surprise Chinese ballistic missile attack against airbases in Japan, more than 200 U.S. aircraft would be trapped or destroyed on the ground in the first hours of the conflict.[8]

Lineage, assignments, stations, and components

Lineage

- Established as Philippine Department Air Force on 16 August 1941

- Activated on 20 September 1941

- Redesignated: Far East Air Force on 16 November 1941

- Redesignated: 5 Air Force on 5 February 1942

- Redesignated: Fifth Air Force* on 18 September 1942.

Fifth Air Force is not to be confused with a second "Fifth" air force created as a temporary establishment to handle combat operations after the outbreak of hostilities on 25 June 1950, in Korea. This numbered air force was established as Fifth Air Force, Advance, and organized at Itazuki AB, Japan, assigned to Fifth Air Force, on 14 July 1950. It moved to Taegu AB, South Korea, on 24 July 1950, and was redesignated Fifth Air Force in Korea at the same time. After moving, it apparently received command control from U.S. Far East Air Forces. The establishment operated from Pusan, Taegu, and Seoul before being discontinued on 1 December 1950.

Assignments

- Philippine Department, U.S. Army, 20 September 1941

- US Forces in Australia (USFIA), 23 December 1941

- Redesignated: US Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA), 5 January 1942

- American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), 23 February 1942

- Allied Air Force, Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), 2 November 1942

- Far East Air Forces (Provisional), 15 June 1944

- Far East Air Forces, 3 August 1944

- Redesignated: Pacific Air Command, United States Army, 6 December 1945

- Redesignated: Far East Air Forces, 1 January 1947

- Redesignated Pacific Air Forces, 1 July 1957—present

Stations

|

|

Major components

Commands

- V Air Force Service: 18 June 1943 – 15 June 1944

- V Air Service Area: 9 January 1944 – 15 June 1944

- 5 Bomber (later, V Bomber): 14 November 1941 – 31 May 1946

- V Fighter: 25 August 1942 – 31 May 1946

- 5 Interceptor: 4 November 1941 – 6 April 1942

- Became Army Air Force Infantry unit during Battle of the Philippines (1941–42) (20 December 1941 – 9 April 1942)

- Far East Air Service (later, 5 Air Force Base; V Air Force Base): 28 October 1941 – 2 November 1942

Divisions

- 39th Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 15 January 1968

- 41st Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 15 January 1968

- 43d Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 1 October 1957

- 313th Air Division: 1 March 1955 – 1 October 1991

- 314th Air Division: 31 May 1946 – 1 March 1950; 1 December 1950 – 18 May 1951; 15 March 1955 – 8 September 1986

- 315 Air Division (formerly, 315 Composite Wing): 1 June 1946 – 1 March 1950.

Wings (incomplete listing)

- 18th Wing: 1 Oct 1991-.

- 35th Fighter Wing: 1 Oct 1994-.

- 51st Fighter Wing: 1955-September 1986

- 374th Airlift Wing: 1 Apr 1992-.

Groups

- 2nd Combat Cargo Group: October 1944-15 January 1946

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fifth Air Force. |

References

![]()

- Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-89201-092-4.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories 1947–1977. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-12-9..

- "Fifth Air Force (PACAF)". af.mil.

- "5TH AIR FORCE". af.mil.

- "Fact Sheet 5th Air Force". 5th Air Force Public Affairs. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-89201-092-4.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- Edmonds, Walter D. 1951, They Fought With What They Had: The Story of the Army Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific, 1941–1942, Office of Air Force History (Zenger Pub June 1982 reprint), ISBN 0-89201-068-1

- "The Fall of the Philippines-Contents". www.history.army.mil.

- Shugart, Thomas & Gonzalez, Javier First Strike: China’s Missile Threat to U.S. Bases in Asia 2017 Retrieved September 16, 2017

Bibliography

- Bartsch, William H. Doomed at the Start: American Pursuit Pilots in the Philippines, 1941–1942. Reveille Books, 1995. ISBN 0-89096-679-6.

- Birdsall, Steve. Flying Buccaneers: The Illustrated History of Kenney's Fifth Air Force. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1977. ISBN 0-385-03218-8.

- Craven, Wesley F. and James L. Cate. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948–58.

- Holmes, Tony. "Twelve to One": V Fighter Command Aces of the Pacific. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-784-0.

- Rust, Kenn C. Fifth Air Force Story...in World War II. Temple City, California: Historical Aviation Album, 1973. ISBN 0-911852-75-1.

External links

- Fifth Air Force Factsheet

- Red Raiders—22nd Bomb Group, 5th Air Force, WW II

- 38th Bomb Group Association

- 43rd Bomb Group Association: Ken's Men

- The Julius Schellenberg Collection at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York includes the diary of 5th Air Force sergeant Julius Schellenberg from February – December 1942 and a photograph of the 5th Air Force in 1942.