Eclipse cycle

Eclipses may occur repeatedly, separated by certain intervals of time: these intervals are called eclipse cycles.[1] The series of eclipses separated by a repeat of one of these intervals is called an eclipse series.

Eclipse conditions

Eclipses may occur when the Earth and the Moon are aligned with the Sun, and the shadow of one body cast by the Sun falls on the other. So at new moon, when the Moon is in conjunction with the Sun, the Moon may pass in front of the Sun as seen from a narrow region on the surface of the Earth and cause a solar eclipse. At full moon, when the Moon is in opposition to the Sun, the Moon may pass through the shadow of the Earth, and a lunar eclipse is visible from the night half of the Earth. Conjunction and opposition of the Moon together have a special name: syzygy (from Greek for "junction"), because of the importance of these lunar phases.

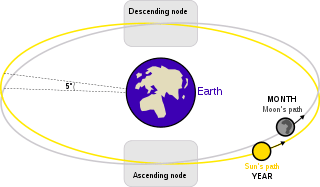

An eclipse does not happen at every new or full moon, because the plane of the orbit of the Moon around the Earth is tilted with respect to the plane of the orbit of the Earth around the Sun (the ecliptic): so as seen from the Earth, when the Moon is nearest to the Sun (new moon) or at largest distance (full moon), the three bodies usually are not exactly on the same line.

This inclination is on average about 5° 9′, much larger than the apparent mean diameter of the Sun (32′ 2″), the Moon as seen from the surface of the Earth right beneath the Moon (31′ 37″), and the shadow of the Earth at the mean lunar distance (1° 23′).

Therefore, at most new moons the Earth passes too far north or south of the lunar shadow, and at most full moons the Moon misses the shadow of the Earth. Also, at most solar eclipses the apparent angular diameter of the Moon is insufficient to fully obscure the solar disc, unless the Moon is near its perigee, i.e. closer to the Earth and apparently larger than average. In any case, the alignment must be close to perfect to cause an eclipse.

An eclipse can only occur when the Moon is close to the plane of the orbit of the Earth, i.e. when its ecliptic latitude is small. This happens when the Moon is near one of the two nodes of its orbit on the ecliptic at the time of the syzygy. Of course, to produce an eclipse, the Sun must also be near a node at that time: the same node for a solar eclipse, or the opposite node for a lunar eclipse.

Recurrence

Up to three eclipses may occur during an eclipse season, a one- or two-month period that happens twice a year, around the time when the Sun is near the nodes of the Moon's orbit.

An eclipse does not occur every month, because one month after an eclipse the relative geometry of the Sun, Moon, and Earth has changed.

As seen from the Earth, the time it takes for the Moon to return to a node, the draconic month, is less than the time it takes for the Moon to return to the same ecliptic longitude as the Sun: the synodic month. The main reason is that during the time that the Moon has completed an orbit around the Earth, the Earth (and Moon) have completed about 1⁄13 of their orbit around the Sun: the Moon has to make up for this in order to come again into conjunction or opposition with the Sun. Secondly, the orbital nodes of the Moon precess westward in ecliptic longitude, completing a full circle in about 18.60 years, so a draconic month is shorter than a sidereal month. In all, the difference in period between synodic and draconic month is nearly 2 1⁄3 days. Likewise, as seen from the Earth, the Sun passes both nodes as it moves along its ecliptic path. The period for the Sun to return to a node is called the eclipse or draconic year: about 346.6201 d, which is about 1⁄20 year shorter than a sidereal year because of the precession of the nodes.

If a solar eclipse occurs at one new moon, which must be close to a node, then at the next full moon the Moon is already more than a day past its opposite node, and may or may not miss the Earth's shadow. By the next new moon it is even further ahead of the node, so it is less likely that there will be a solar eclipse somewhere on Earth. By the next month, there will certainly be no event.

However, about 5 or 6 lunations later the new moon will fall close to the opposite node. In that time (half an eclipse year) the Sun will have moved to the opposite node too, so the circumstances will again be suitable for one or more eclipses.

Periodicity

These are still rather vague predictions. However we know that if an eclipse occurred at some moment, then there will occur an eclipse again S synodic months later, if that interval is also D draconic months, where D is an integer number (return to same node), or an integer number + ½ (return to opposite node). So an eclipse cycle is any period P for which approximately holds:

- P = S×(synodic month length) = D×(Draconic month length)

Given an eclipse, then there is likely to be another eclipse after every period P. This remains true for a limited time, because the relation is only approximate.

Another thing to consider is that the motion of the Moon is not a perfect circle. Its orbit is distinctly elliptic, so the lunar distance from Earth varies throughout the lunar cycle. This varying distance changes the apparent diameter of the Moon, and therefore influences the chances, duration, and type (partial, annular, total, mixed) of an eclipse. This orbital period is called the anomalistic month, and together with the synodic month causes the so-called "full moon cycle" of about 14 lunations in the timings and appearances of full (and new) Moons. The Moon moves faster when it is closer to the Earth (near perigee) and slower when it is near apogee (furthest distance), thus periodically changing the timing of syzygies by up to ±14 hours (relative to their mean timing), and changing the apparent lunar angular diameter by about ±6%. An eclipse cycle must comprise close to an integer number of anomalistic months in order to perform well in predicting eclipses.

Numerical values

These are the lengths of the various types of months as discussed above (according to the lunar ephemeris ELP2000-85, valid for the epoch J2000.0; taken from (e.g.) Meeus (1991) ):

- SM = 29.530588853 days (Synodic month)[2]

- DM = 27.212220817 days (Draconic month)[3]

- AM = 27.55454988 days (Anomalistic month)[4]

- EY = 346.620076 days (Eclipse year)

Note that there are three main moving points: the Sun, the Moon, and the (ascending) node; and that there are three main periods, when each of the three possible pairs of moving points meet one another: the synodic month when the Moon returns to the Sun, the draconic month when the Moon returns to the node, and the eclipse year when the Sun returns to the node. These three 2-way relations are not independent (i.e. both the synodic month and eclipse year are dependent on the apparent motion of the Sun, both the draconic month and eclipse year are dependent on the motion of the nodes), and indeed the eclipse year can be described as the beat period of the synodic and draconic months (i.e. the period of the difference between the synodic and draconic months); in formula:

as can be checked by filling in the numerical values listed above.

Eclipse cycles have a period in which a certain number of synodic months closely equals an integer or half-integer number of draconic months: one such period after an eclipse, a syzygy (new moon or full moon) takes place again near a node of the Moon's orbit on the ecliptic, and an eclipse can occur again. However, the synodic and draconic months are incommensurate: their ratio is not an integer number. We need to approximate this ratio by common fractions: the numerators and denominators then give the multiples of the two periods – draconic and synodic months – that (approximately) span the same amount of time, representing an eclipse cycle.

These fractions can be found by the method of continued fractions: this arithmetical technique provides a series of progressively better approximations of any real numeric value by proper fractions.

Since there may be an eclipse every half draconic month, we need to find approximations for the number of half draconic months per synodic month: so the target ratio to approximate is: SM / (DM/2) = 29.530588853 / (27.212220817/2) = 2.170391682

The continued fractions expansion for this ratio is:

2.170391682 = [2;5,1,6,1,1,1,1,1,11,1,...]:[5] Quotients Convergents half DM/SM decimal named cycle (if any) 2; 2/1 = 2 5 11/5 = 2.2 1 13/6 = 2.166666667 semester 6 89/41 = 2.170731707 hepton 1 102/47 = 2.170212766 octon 1 191/88 = 2.170454545 tzolkinex 1 293/135 = 2.170370370 tritos 1 484/223 = 2.170403587 saros 1 777/358 = 2.170391061 inex 11 9031/4161 = 2.170391732 1 9808/4519 = 2.170391679 ...

The ratio of synodic months per half eclipse year yields the same series:

5.868831091 = [5;1,6,1,1,1,1,1,11,1,...]

Quotients Convergents

SM/half EY decimal SM/full EY named cycle

5; 5/1 = 5

1 6/1 = 6 12/1 semester

6 41/7 = 5.857142857 hepton

1 47/8 = 5.875 47/4 octon

1 88/15 = 5.866666667 tzolkinex

1 135/23 = 5.869565217 tritos

1 223/38 = 5.868421053 223/19 saros

1 358/61 = 5.868852459 716/61 inex

11 4161/709 = 5.868829337

1 4519/770 = 5.868831169 4519/385

...

Each of these is an eclipse cycle. Less accurate cycles may be constructed by combinations of these.

Eclipse cycles

This table summarizes the characteristics of various eclipse cycles, and can be computed from the numerical results of the preceding paragraphs; cf. Meeus (1997) Ch.9. More details are given in the comments below, and several notable cycles have their own pages.

Any eclipse cycle, and indeed the interval between any two eclipses, can be expressed as a combination of saros (s) and inex (i) intervals. These are listed in the column "formula".

| Cycle | Formula | Solar days | Synodic months | Draconic months | Anomalistic months | Eclipse years | Tropical years | Eclipse seasons | Node |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fortnight | 19i − 30 1⁄2s | 14.77 | 0.5 | 0.543 | 0.536 | 0.043 | 0.040 | 0.086 | alternate |

| synodic month | 38i − 61s | 29.53 | 1 | 1.085 | 1.072 | 0.085 | 0.081 | 0.17 | same |

| pentalunex | 53s − 33i | 147.65 | 5 | 5.426 | 5.359 | 0.426 | 0.404 | 0.852 | alternate |

| semester | 5i − 8s | 177.18 | 6 | 6.511 | 6.430 | 0.511 | 0.485 | 1 | alternate |

| lunar year | 10i − 16s | 354.37 | 12 | 13.022 | 12.861 | 1.022 | 0.970 | 2 | same |

| hepton | 5s − 3i | 1210.73 | 41 | 44.485 | 43.952 | 3.485 | 3.321 | 7 | alternate |

| octon | 2i − 3s | 1387.94 | 47 | 51.004 | 50.371 | 4.004 | 3.800 | 8 | same |

| tzolkinex | 2s − i | 2598.69 | 88 | 95.497 | 94.311 | 7.497 | 7.115 | 15 | alternate |

| sar (half saros) | 1⁄2s | 3292.66 | 111.5 | 120.999 | 119.496 | 9.499 | 9.015 | 19 | same |

| tritos | i − s | 3986.63 | 135 | 146.501 | 144.681 | 11.501 | 10.915 | 23 | alternate |

| saros (s) | s | 6585.32 | 223 | 241.999 | 238.992 | 18.999 | 18.030 | 38 | same |

| Metonic cycle | 10i − 15s | 6939.69 | 235 | 255.021 | 251.853 | 20.021 | 19.000 | 40 | same |

| inex (i) | i | 10,571.95 | 358 | 388.500 | 383.674 | 30.500 | 28.945 | 61 | alternate |

| exeligmos | 3s | 19,755.96 | 669 | 725.996 | 716.976 | 56.996 | 54.090 | 114 | same |

| Callippic cycle | 40i − 60s | 27,758.75 | 940 | 1020.084 | 1007.411 | 80.084 | 76.001 | 160 | same |

| triad | 3i | 31,715.85 | 1074 | 1165.500 | 1151.021 | 91.500 | 86.835 | 183 | alternate |

| Hipparchic cycle | 25i − 21s | 126,007.02 | 4267 | 4630.531 | 4573.002 | 363.531 | 344.996 | 727 | alternate |

| Babylonian | 14i + 2s | 161,177.95 | 5458 | 5922.999 | 5849.413 | 464.999 | 441.291 | 930 | same |

| tetradia (Meeus III) | 22i − 4s | 206,241.63 | 6984 | 7579.008 | 7484.849 | 595.008 | 564.671 | 1190 | same |

| tetradia (Meeus [I]) | 19i + 2s | 214,037.70 | 7248 | 7865.500 | 7767.781 | 617.500 | 586.016 | 1235 | alternate |

Notes:

- Fortnight

- Half a synodic month (29.53 days). When there is an eclipse, there is a fair chance that at the next syzygy there will be another eclipse: the Sun and Moon will have moved about 15° with respect to the nodes (the Moon being opposite to where it was the previous time), but the luminaries may still be within bounds to make an eclipse. For example, partial solar eclipse of June 1, 2011 is followed by the total lunar eclipse of June 15, 2011 and partial solar eclipse of July 1, 2011.

- For more information see eclipse season.

- Synodic month

- Similarly, two events one synodic month apart have the Sun and Moon at two positions on either side of the node, 29° apart: both may cause a partial eclipse. For a lunar eclipse, it is a penumbral lunar eclipse.

- Pentalunex

- 5 synodic months. Successive solar or lunar eclipses may occur 1, 5 or 6 synodic months apart.[6]

- Semester

- Half a lunar year. Eclipses will repeat exactly one semester apart at alternating nodes in a cycle that lasts for 8 eclipses. Because it is close to a half integer of anomalistic, draconic months, and tropical years, each solar eclipse will alternate between hemispheres each semester, as well as alternate between total and annular. Hence there can be a maximum of one total or annular eclipse each in a given year. (For a lunar eclipse, eclipses will repeat exactly one semester apart at alternating nodes in a cycle that lasts for 8 eclipses. Because it is close to a half integer of anomalistic, draconic months, and tropical years, each lunar eclipse will alternate between edges of Earth’s shadow each semester, as well as alternate between Lunar Perigee and Lunar Apogee. Hence there can be a maximum of one Lunar Perigee or Lunar Apogee each in a given year.)

- Lunar year

- Twelve (synodic) months, a little longer than an eclipse year: the Sun has returned to the node, so eclipses may again occur.

- Octon

- This is 1⁄5 of the Metonic cycle, and a fairly decent short eclipse cycle, but poor in anomalistic returns. Each octon in a series is 2 saros apart, always occurring at the same node. For solar (or lunar) eclipses, it is equal to 47 synodic months (1388 solar days).

- Tzolkinex

- Includes a half draconic month, so occurs at alternating nodes and alternates between hemispheres. Each consecutive eclipse is a member of preceding saros series from the one before. Equal to ten tzolk'ins. Every third tzolkinex in a series is near an integer number of anomalistic months and so will have similar properties.

- Sar (half saros)

- Includes an odd number of fortnights (223). As a result, eclipses alternate between lunar and solar with each cycle, occurring at the same node and with similar characteristics. A solar eclipse with small gamma will be followed by a very central total lunar eclipse. A solar eclipse where the moon's penumbra just barely grazes the southern limb of earth will be followed half a saros later by a lunar eclipse where the moon just grazes the southern limb of the earth's penumbra.[7]

- Tritos

- A mediocre cycle, relates to the saros like the inex. A triple tritos is close to an integer number of anomalistic months and so will have similar properties.

- Saros

- The best known eclipse cycle, and one of the best for predicting eclipses, in which 223 synodic months equal 242 draconic months with an error of only 51 minutes. It is also close to 239 anomalistic months, which makes the circumstances between two eclipses one saros apart very similar.

- Metonic cycle or enneadecaeteris

- This is nearly equal to 19 tropical years, but is also 5 "octon" periods and close to 20 eclipse years: so it yields a short series of eclipses on the same calendar date. It consists of 110 hollow months and 125 full months, so nominally 6940 days, and equals 235 lunations (235 synodic months) with an error of only around 7.5 hours.

- Inex

- Very convenient in the classification of eclipse cycles. Inex series, after a sputtering beginning, go on for many thousands of years giving eclipses every 29 years or so. One inex after an eclipse, another eclipse takes place at almost the same longitude, but at the opposite latitude.

- Exeligmos

- A triple saros, with the advantage that it has nearly an integer number of days, so the next eclipse will be visible at locations near the eclipse that occurred one exeligmos earlier, in contrast to the saros, in which the eclipse occurs about 8 hours later in the day or about 120° to the west of the eclipse that occurred one saros earlier.

- Callippic cycle

- 441 hollow months and 499 full months; thus 4 Metonic cycles minus one day or precisely 76 years of 365 1⁄4 days. It equals 940 lunations with an error of only 5.9 hours.

- Triad

- A triple inex, with the advantage that it has nearly an integer number of anomalistic months, which makes the circumstances between two eclipses one Triad apart very similar, but at the opposite latitude. Almost exactly 87 calendar years minus 2 months. The triad means that every third saros series will be similar (mostly total central eclipses or annular central eclipses for example). Saros 130, 133, 136, 139, 142 and 145, for example, all produce mainly total central eclipses.

- Hipparchic cycle

- Not a noteworthy eclipse cycle, but Hipparchus constructed it to closely match an integer number of synodic and anomalistic months, years (345), and days. By comparing his own eclipse observations with Babylonian records from 345 years earlier, he could verify the accuracy of the various periods that the Chaldeans used.

- Babylonian

- The ratio 5923 returns to latitude in 5458 months was used by the Chaldeans in their astronomical computations.

- Tetradia

- Sometimes 4 total lunar eclipses occur in a row with intervals of 6 lunations (semester), and this is called a tetrad. Giovanni Schiaparelli noticed that there are eras when such tetrads occur comparatively frequently, interrupted by eras when they are rare. This variation takes about 6 centuries. Antonie Pannekoek (1951) offered an explanation for this phenomenon and found a period of 591 years. Van den Bergh (1954) from Theodor von Oppolzer's Canon der Finsternisse found a period of 586 years. This happens to be an eclipse cycle; see Meeus [I] (1997). Recently Tudor Hughes explained the variation from secular changes in the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit: the period for occurrence of tetrads is variable and currently is about 565 years; see Meeus III (2004) for a detailed discussion.

Saros series and inex series

Any eclipse can be assigned to a given saros series and inex series. The year of a solar eclipse (in the Gregorian calendar) is then given approximately by:[8]

- year = 28.945 × number of the saros series + 18.030 × number of the inex series − 2882.55

When this is greater than 1, the integer part gives the year AD, but when it is negative the year BC is obtained by taking the integer part and adding 2. For instance, the eclipse in saros series zero and inex series zero was in the middle of 2884 BC.

See also

References

- properly, these are periods, not cycles

- Meeus (1991) form. 47.1

- Meeus (1991) ch. 49 p.334

- Meeus (1991) form. 48.1

- 2.170391682 = 2 + 0.170391682 ; 1/0.170391682 = 5 + 0.868831085... ; 1/0.868831085... = 1 + 0.15097171... ; 1/0.15097171 = 6 + 0.6237575... ; etc. ; Evaluating this 4th continued fraction: 1/6 + 1 = 7/6; 6/7 + 5 = 41/7 ; 7/41 + 2 = 89/41

- A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles, Robert Harry van Gent

- A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles, Robert Harry van Gent

- Based on Saros, Inex and Eclipse cycles.

- S. Newcomb (1882): On the recurrence of solar eclipses. Astron.Pap.Am.Eph. vol. I pt. I . Bureau of Navigation, Navy Dept., Washington 1882

- J.N. Stockwell (1901): Eclips-cycles. Astron.J. 504 [vol.xx1(24)], 14-Aug-1901

- A.C.D. Crommelin (1901): The 29-year eclipse cycle. Observatory xxiv nr.310, 379, Oct-1901

- A. Pannekoek (1951): Periodicities in Lunar Eclipses. Proc. Kon. Ned. Acad. Wetensch. Ser.B vol.54 pp. 30..41 (1951)

- G. van den Bergh (1954): Eclipses in the second millennium B.C. Tjeenk Willink & Zn NV, Haarlem 1954

- G. van den Bergh (1955): Periodicity and Variation of Solar (and Lunar) Eclipses, 2 vols. Tjeenk Willink & Zn NV, Haarlem 1955

- Jean Meeus (1991): Astronomical Algorithms (1st ed.). Willmann-Bell, Richmond VA 1991; ISBN 0-943396-35-2

- Jean Meeus (1997): Mathematical Astronomy Morsels [I], Ch.9 Solar Eclipses: Some Periodicities (pp. 49..55). Willmann-Bell, Richmond VA 1997; ISBN 0-943396-51-4

- Jean Meeus (2004): Mathematical Astronomy Morsels III, Ch.21 Lunar Tetrads (pp. 123..140). Willmann-Bell, Richmond VA 2004; ISBN 0-943396-81-6

External links

- A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles (more comprehensive than the above)

- Search 5,000 years worth of eclipses

- Eclipses, Cosmic Clockwork of the Ancients

- The Saros and the Inex

.jpg)