Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

The demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States encompass the gender, ethnicity, and religious, geographic, and economic backgrounds of the 114 people who have been appointed and confirmed as justices to the Supreme Court. Some of these characteristics have been raised as an issue since the Court was established in 1789. For its first 180 years, justices were almost always white male Protestant of Anglo or Northwestern European descent.[1]

| This article is part of the series on the |

| United States Supreme Court |

|---|

|

| The Court |

| Current membership |

| Lists of justices |

|

| Court functionaries |

|

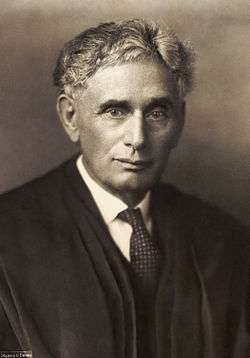

Prior to the 20th century, a few Roman Catholics were appointed, but concerns about diversity of the Court were mainly in terms of geographic diversity, to represent all geographic regions of the country, as opposed to ethnic, religious, or gender diversity.[2] The 20th century saw the first appointment of justices who were Jewish (Louis Brandeis, 1916), African-American (Thurgood Marshall, 1967), female (Sandra Day O'Connor, 1981), and Italian-American (Antonin Scalia, 1986). The first appointment of a Hispanic justice was in the 21st century with Sonia Sotomayor in 2009, with the possible exception of justice Benjamin Cardozo, a Sephardi Jew of Portuguese descent, who was appointed in 1932.

In spite of the interest in the Court's demographics and the symbolism accompanying the inevitably political appointment process,[3] and the views of some commentators that no demographic considerations should arise in the selection process,[4][5] the gender, race, educational background or religious views of the justices has played little documented role in their jurisprudence. For example, the opinions of the two African-American justices have reflected radically different judicial philosophies; William Brennan and Antonin Scalia shared Catholic faith and a Harvard Law School education, but shared little in the way of jurisprudential philosophies. The court's first two female justices voted together no more often than with their male colleagues, and historian Thomas R. Marshall writes that no particular "female perspective" can be discerned from their opinions.[6]

Geographic background

For most of the existence of the Court, geographic diversity was a key concern of presidents in choosing justices to appoint.[2] This was prompted in part by the early practice of Supreme Court justices also "riding circuit"—individually hearing cases in different regions of the country. In 1789, the United States was divided into judicial circuits, and from that time until 1891, Supreme Court justices also acted as judges within those individual circuits.[7] George Washington was careful to make appointments "with no two justices serving at the same time hailing from the same state".[8] Abraham Lincoln broke with this tradition during the Civil War,[7] and "by the late 1880s presidents disregarded it with increasing frequency".[9]

Although the importance of regionalism declined, it still arose from time to time. For example, in appointing Benjamin Cardozo in 1929, President Hoover was as concerned about the controversy over having three New York justices on the Court as he was about having two Jewish justices.[10] David M. O'Brien notes that "[f]rom the appointment of John Rutledge from South Carolina in 1789 until the retirement of Hugo Black [from Alabama] in 1971, with the exception of the Reconstruction decade of 1866–1876, there was always a southerner on the bench. Until 1867, the sixth seat was reserved as the 'southern seat'. Until Cardozo's appointment in 1932, the third seat was reserved for New Englanders."[11] The westward expansion of the U.S. led to concerns that the western states should be represented on the Court as well, which purportedly prompted William Howard Taft to make his 1910 appointment of Willis Van Devanter of Wyoming.[12]

Geographic balance was sought in the 1970s, when Nixon attempted to employ a "Southern strategy", hoping to secure support from Southern states by nominating judges from the region.[1] Nixon unsuccessfully nominated Southerners Clement Haynsworth of South Carolina and G. Harrold Carswell of Georgia, before finally succeeding with the nomination of Harry Blackmun of Minnesota.[13] The issue of regional diversity was again raised with the 2010 retirement of John Paul Stevens, who had been appointed from the midwestern Seventh Circuit, leaving the Court with all but one Justice having been appointed from states on the East Coast.[14]

As of 2017, the Court has a majority from the Northeastern United States, with six justices coming from states to the north and east of Washington, D.C. including four justices born or raised in New York City. The remaining three justices come from Georgia, California and Colorado; the most recent justice from the Midwest being John Paul Stevens of Illinois who retired in 2010. Contemporary Justices may be associated with multiple states. Many nominees are appointed while serving in states or districts other than their hometown or home state. Chief Justice John Roberts, for example, was born in New York, but moved to Indiana at the age of five, where he grew up. After law school, Roberts worked in Washington, D.C. while living in Maryland. Thus, three states may claim his domicile.

Despite the efforts to achieve geographic balance, only seven justices[lower-alpha 1] have ever hailed from states admitted after or during the Civil War. Nineteen states have never produced a Supreme Court Justice; in chronological order of admission to the Union these are:

- Delaware (original state)

- Rhode Island (original state)

- Vermont (admitted in 1791)

- Arkansas (admitted in 1836)

- Florida (admitted in 1845)

- Wisconsin (admitted in 1848)

- Oregon (admitted in 1859)

- West Virginia (admitted in 1863)[lower-alpha 2]

- Nevada (admitted in 1864)

- Nebraska (admitted in 1867)

- North Dakota (admitted in 1889)

- South Dakota (admitted in 1889)

- Montana (admitted in 1889)

- Washington (admitted in 1889)

- Idaho (admitted in 1890)

- Oklahoma (admitted in 1907)

- New Mexico (admitted in 1912)

- Alaska (admitted in 1959) and

- Hawaii (admitted in 1959)

In contrast, some states have been over-represented, partly because there were fewer states from which early justices could be appointed. New York has produced fifteen justices, Ohio ten, Massachusetts nine, Virginia eight, six each from Pennsylvania and Tennessee, and five from Kentucky, Maryland, and New Jersey.[13] A handful of justices were born outside the United States, mostly from among the earliest justices on the Court. These included James Wilson, born in Fife, Scotland; James Iredell, born in Lewes, England; and William Paterson, born in County Antrim, Ireland. Justice David Josiah Brewer was born farthest from the U.S., in Smyrna, in the Ottoman Empire, (now İzmir, Turkey). George Sutherland was born in Buckinghamshire, England. The last foreign-born Justice, and the only one of these for whom English was a second language, was Felix Frankfurter, born in Vienna, Austria.[15] The Constitution imposes no citizenship requirement on federal judges.

Ethnicity

All Supreme Court justices were white and of European heritage until the appointment of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Justice, in 1967. Since then, only two other non-white Justices have been appointed, Marshall's African-American successor, Clarence Thomas in 1991, and Latina Justice Sonia Sotomayor in 2009.

Foreign birth

There have been six foreign-born justices in the Court's history: James Wilson (1789-1798), born in Caskardy, Scotland; James Iredell (1790-1799), born in Lewes, England; William Paterson (1793-1806), born in County Antrim, Ireland; David Brewer (1889-1910), born to American missionary parents in Smyrna, Ottoman Empire (now İzmir, Turkey);[16] George Sutherland (1922-1939), born in Buckinghamshire, England; and Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962), born in Vienna, Austria.[17]

White justices

The vast majority of white justices have been of Northern European, Northwestern European, or Germanic Protestant descent. There have been several justices of Irish descent with William Paterson born in Ireland to an Ulster Scots Protestant family and Joseph McKenna, Edward Douglas White, Pierce Butler, Frank Murphy, William J. Brennan Jr., Anthony Kennedy, and Brett Kavanaugh being of Irish Catholic origin. Up until the 1980s, only six justices of "central, eastern, or southern European derivation" had been appointed, and even among these six justices, five of them "were of Germanic background, which includes Austrian, German-Bohemian, and Swiss origins (John Catron, Samuel F. Miller, Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter, and Warren Burger)", with Brandeis and Frankfurter being of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, while only one justice was of non-Germanic, Southern European descent (Benjamin N. Cardozo, of Sephardic Jewish descent).[18] Cardozo, appointed to the Court in 1932, was the first justice known to have non-Germanic, non-Anglo-Saxon or non-Irish ancestry and the first justice of Southern European descent.. Both of Justice Cardozo's parents descended from Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who fled to Holland during the Spanish Inquisition then to London, before arriving in New York prior to the American Revolution.[19] Justice Antonin Scalia, who served from 1986-2016, and Justice Samuel Alito, who has served since 2006, are the first justices of Italian descent to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Justice Scalia's father and both maternal grandparents as well as both of Justice Alito's parents were born in Italy.[20][21][22] Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was born to a Jewish father who immigrated from Russia at age 13 and a Jewish mother who was born four months after her parents immigrated from Poland.[23]

African American justices

No African-American candidate was given serious consideration for appointment to the Supreme Court until the election of John F. Kennedy, who weighed the possibility of appointing William H. Hastie of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.[24] Hastie had been the first African-American elevated to a Court of Appeals when Harry S. Truman had so appointed him in 1949, and by the time of the Kennedy Administration, it was widely anticipated that Hastie might be appointed to the Supreme Court.[25] That Kennedy gave serious consideration to making this appointment "represented the first time in American history that an African American was an actual contender for the high court".[24]

The first African American appointed to the Court was Thurgood Marshall, appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967. The second was Clarence Thomas, appointed by George H. W. Bush to succeed Marshall in 1991.

Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court following the retirement of Justice Tom C. Clark, saying that this was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place." Marshall was confirmed as an Associate Justice by a Senate vote of 69–11 on August 31, 1967.[26] Johnson confidently predicted to one biographer, Doris Kearns Goodwin, that a lot of black baby boys would be named "Thurgood" in honor of this choice (in fact, Kearns's research of birth records in New York and Boston indicates that Johnson's prophecy did not come true).[27]

Bush initially wanted to nominate Thomas to replace William Brennan, who stepped down in 1990, but he then decided that Thomas had not yet had enough experience as a judge after only months on the federal bench.[28] Bush therefore nominated New Hampshire Supreme Court judge David Souter (who is not African American) instead.[28] The selection of Thomas to instead replace Marshall preserved the existing racial composition of the court.

Hispanic and Latino justices

The words "Latino" and "Hispanic" are sometimes given distinct meanings, with "Latino" referring to persons of Latin American descent, and "Hispanic" referring to persons having an ancestry, language or culture traceable to Spain or to the Iberian Peninsula as a whole, as well as to persons of Latin American descent, whereas the term "Lusitanic" usually refers to persons having an ancestry, language or culture traceable to Portugal specifically.

Sonia Sotomayor—nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and sworn in on August 8—is the first Supreme Court Justice of Latin American descent. Born in New York City of Puerto Rican parents, she has been known to refer to herself as a "Nuyorican". Sotomayor is also generally regarded as the first Hispanic justice, although some sources claim that this distinction belongs to former Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo.

It has been claimed that "only since the George H. W. Bush administration have Hispanic candidates received serious consideration from presidents in the selection process",[29] and that Emilio M. Garza (considered for the vacancy eventually given to Clarence Thomas[30]) was the first Hispanic judge for whom such an appointment was contemplated.[31] Subsequently, Bill Clinton was reported by several sources to have considered José A. Cabranes for a Supreme Court nomination on both occasions when a Court vacancy opened during the Clinton presidency.[32][33] The possibility of a Hispanic Justice returned during the George W. Bush Presidency, with various reports suggesting that Emilio M. Garza,[34] Alberto Gonzales,[35] and Consuelo M. Callahan[36] were under consideration for the vacancy left by the retirement of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor's seat eventually went to Samuel Alito, however. Speculation about a Hispanic nomination arose again after the election of Barack Obama.[37] In 2009, Obama appointed Sonia Sotomayor, a woman of Puerto Rican descent, to be the first unequivocally Hispanic Justice.[38] Both the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials and the Hispanic National Bar Association count Sotomayor as the first Hispanic justice.[39][40]

Some historians contend that Cardozo—a Sephardic Jew believed to be of distant Portuguese descent[41]—should also be counted as the first Hispanic Justice.[1] Schmidhauser wrote in 1979 that "[a]mong the large ethnic groupings of European origin which have never been represented upon the Supreme Court are the Italians, Southern Slavs, and Hispanic Americans."[18] The National Hispanic Center for Advanced Studies and Policy Analysis wrote in 1982 that the Supreme Court "has never had an Hispanic Justice",[42] and the Hispanic American Almanac similarly reported in 1996 that "no Hispanic has yet sat on the U.S. Supreme Court".[43] However, Segal and Spaeth state: "Though it is often claimed that no Hispanics have served on the Court, it is not clear why Benjamin Cardozo, a Sephardic Jew of Spanish heritage, should not count." They identify a number of other sources that present conflicting views as to Cardozo's ethnicity, with one simply labeling him "Iberian." In 2007, the Dictionary of Latino Civil Rights History also listed Cardozo as "the first Hispanic named to the Supreme Court of the United States." [44]

The nomination of Sonia Sotomayor, widely described in media accounts as the first Hispanic nominee, drew more attention to the question of Cardozo's ethnicity.[39][40][45][46] Cardozo biographer Andrew Kaufman questioned the usage of the term "hispanic" during Cardozo's lifetime, commenting: "Well, I think he regarded himself as Sephardic Jew whose ancestors came from the Iberian Peninsula."[39] However, "no one has ever firmly established that the family's roots were, in fact, in Portugal".[47] It has also been asserted that Cardozo himself "confessed in 1937 that his family preserved neither the Spanish language nor Iberian cultural traditions".[48] By contrast, Cardozo made his own translations of authoritative legal works written in French and German.[49]

Ethnic groups that have never been represented

Many ethnic groups have never been represented on the Court. There has never been a Justice with any Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander heritage, and no person having such a heritage was publicly considered for an appointment until the 21st century. Legal scholar Viet D. Dinh, of Vietnamese descent, was named as a potential George W. Bush nominee.[50] During the presidency of Barack Obama, potential nominees included Harold Hongju Koh, of Korean descent, and former Idaho attorney general Larry Echo Hawk, a member of the Pawnee tribe.[51] Indian-American federal judge Amul Thapar was included in a list of individuals Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump "would consider as potential replacements for Justice Scalia at the United States Supreme Court."[52][53] and was one of six judges interviewed by President Trump in July 2018 while being considered to fill the vacancy left by the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy.[54][55]

Public opinion on ethnic diversity

Public opinion about ethnic diversity on the court "varies widely depending on the poll question's wording".[6] For example, in two polls taken in 1991, one resulted in half of respondents agreeing that it was "important that there always be at least one black person" on the Court while the other had only 20% agreeing with that sentiment, and with 77% agreeing that "race should never be a factor in choosing Supreme Court justices".[6]

Gender

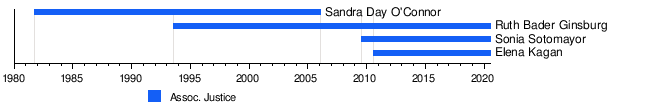

Of the 114 justices, 110 (96.5%) have been men. All Supreme Court justices were males until 1981, when Ronald Reagan fulfilled his 1980 campaign promise to place a woman on the Court,[56] which he did with the appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor was later joined on the Court by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, appointed by Bill Clinton in 1993. After O'Connor retired in 2006, Ginsburg would be joined by Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, who were successfully appointed to the Court in 2009 and 2010, respectively, by Barack Obama.[57] The only other woman to be nominated to the Court was Harriet Miers, whose nomination to succeed O'Connor by George W. Bush was withdrawn under fire.

Substantial public sentiment in support of appointment of a woman to the Supreme Court has been expressed since at least as early as 1930, when an editorial in the Christian Science Monitor encouraged Herbert Hoover to consider Ohio justice Florence E. Allen or assistant attorney general Mabel Walker Willebrandt.[58] Franklin Delano Roosevelt later appointed Allen to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit—making her "one of the highest ranking female jurists in the world at that time".[59] However, neither Roosevelt nor his successors over the following two decades gave strong consideration to female candidates for the Court. Harry Truman considered such an appointment, but was dissuaded by concerns raised by justices then serving that a woman on the Court "would inhibit their conference deliberations", which were marked by informality.[59]

President Richard Nixon named Mildred Lillie, then serving on the Second District Court of Appeal of California, as a potential nominee to fill one of two vacancies on the Court in 1971.[56] However, Lillie was quickly deemed unqualified by the American Bar Association, and no formal proceedings were ever set with respect to her potential nomination. Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist were then successfully nominated to fill those vacancies.

| Name | State | Birth | Death | Year appointed |

Left office |

Appointed by | Reason for termination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandra Day O'Connor | Arizona | 1930 | living | 1981 | 2006 | Reagan | retirement |

| Ruth Bader Ginsburg | New York | 1933 | living | 1993 | incumbent | Clinton | — |

| Sonia Sotomayor | New York | 1954 | living | 2009 | incumbent | Obama | — |

| Elena Kagan | New York | 1960 | living | 2010 | incumbent | Obama | — |

Graphical timeline of female justices:

Public opinion on gender diversity

In 1991, a poll found that 53% of Americans felt it "important that there always be at least one woman" on the Court.[6] However, when O'Connor stepped down from the court, leaving Justice Ginsburg as the lone remaining woman, only one in seven persons polled found it "essential that a woman be nominated to replace" O'Connor.[6]

Marital status and sexual orientation

Marital status

All but a handful of Supreme Court justices have been married. Frank Murphy, Benjamin Cardozo, and James McReynolds were all lifelong bachelors.[60] In addition, retired justice David Souter and current justice Elena Kagan have never been married.[61][62] William O. Douglas was the first Justice to divorce while on the Court, and also had the most marriages of any Justice, with four.[60] Justice John Paul Stevens divorced his first wife in 1979, marrying his second wife later that year. Sonia Sotomayor was the first female justice to be appointed as an unmarried woman, having divorced in 1983, long before her nomination in 2009.[60][62]

Several justices have become widowers while on the bench. The 1792 death of Elizabeth Rutledge, wife of Justice John Rutledge, contributed to the mental health problems that led to the rejection of his recess appointment.[63] Roger B. Taney survived his wife, Anne, by twenty years. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. resolutely continued working on the Court for several years after the death of his wife.[64] William Rehnquist was a widower for the last fourteen years of his service on the Court, his wife Natalie having died on October 17, 1991 after suffering from ovarian cancer.[65] With the death of Martin D. Ginsburg in June 2010, Ruth Bader Ginsburg became the first woman to be widowed while serving on the Court.[66]

Sexual orientation

With regard to sexual orientation, no Supreme Court justice has identified himself or herself as anything other than heterosexual, and no incontrovertible evidence of a justice having any other sexual orientation has ever been uncovered. However, the personal lives of several justices and nominees have attracted speculation.

G. Harrold Carswell was unsuccessfully nominated by Richard Nixon in 1970, and was convicted in 1976 of battery for making an "unnatural and lascivious" advance to a male police officer working undercover in a Florida men's room.[67] Some therefore claim him as the only gay or bisexual person nominated to the Court thus far.[68][69] If so, it is unlikely that Nixon was aware of it; White House Counsel John Dean later wrote of Carswell that "[w]hile Richard Nixon was always looking for historical firsts, nominating a homosexual to the high court would not have been on his list".[69]

Speculation has been recorded about the sexual orientation of a few justices who were lifelong bachelors, but no unambiguous evidence exists that they were gay. Perhaps the greatest body of circumstantial evidence surrounds Frank Murphy, who was dogged by "[r]umors of homosexuality [...] all his adult life".[70]

For more than 40 years, Edward G. Kemp was Frank Murphy's devoted, trusted companion. Like Murphy, Kemp was a lifelong bachelor. From college until Murphy's death, the pair found creative ways to work and live together. [...] When Murphy appeared to have the better future in politics, Kemp stepped into a supportive, secondary role.[71]

As well as Murphy's close relationship with Kemp, Murphy's biographer, historian Sidney Fine, found in Murphy's personal papers a letter that "if the words mean what they say, refers to a homosexual encounter some years earlier between Murphy and the writer." However, the letter's veracity cannot be confirmed and a review of all the evidence led Fine to conclude that he "could not stick his neck out and say [Murphy] was gay".[72]

Speculation has also surrounded Benjamin Cardozo, whose celibacy suggests repressed homosexuality or asexuality. The fact that he was unmarried and was personally tutored by the writer Horatio Alger (alleged to have had sexual relations with boys) led some of Cardozo's biographers to insinuate that Cardozo was homosexual, but no real evidence exists to corroborate this possibility. Constitutional law scholar Jeffrey Rosen noted in a The New York Times Book Review of Richard Polenberg's book on Cardozo:

Polenberg describes Cardozo's lifelong devotion to his older sister Nell, with whom he lived in New York until her death in 1929. When asked why he had never married, Cardozo replied, quietly and sadly, "I never could give Nellie the second place in my life." Polenberg suggests that friends may have stressed Cardozo's devotion to his sister to discourage rumors "that he was sexually dysfunctional, or had an unusually low sexual drive or was homosexual." But he produces no evidence to support any of these possibilities, except to note that friends, in describing Cardozo, used words like "beautiful", "exquisite", "sensitive" or "delicate."[73]

Andrew Kaufman, author of Cardozo, a biography published in 2000, notes that "Although one cannot be absolutely certain, it seems highly likely that Cardozo lived a celibate life".[74] Judge Learned Hand is quoted in the book as saying about Cardozo: "He [had] no trace of homosexuality anyway".[75]

More recently, when David Souter was nominated to the Court, "conservative groups expressed concern to the White House... that the president's bachelor nominee might conceivably be a homosexual".[76] Similar questions were raised regarding the sexual orientation of unmarried nominee Elena Kagan.[77] However, no evidence was ever produced regarding Souter's sexual orientation, and Kagan's apparent heterosexuality was attested by colleagues familiar with her dating history.[78]

Religion

When the Supreme Court was established in 1789, the first members came from among the ranks of the Founding Fathers and were almost uniformly Protestant. Of the 114 justices who have been appointed to the court, 91 have been from various Protestant denominations, 13 have been Catholics (one other justice, Sherman Minton, converted to Catholicism after leaving the Court). Another, Neil Gorsuch, was raised in the Catholic Church but later attended an Episcopal church, though without specifying the denomination to which he felt he belonged.[79] Eight have been Jewish and one, David Davis, had no known religious affiliation. Three of the 17 chief justices have been Catholics, and one Jewish justice, Abe Fortas, was unsuccessfully nominated to be chief justice.

The table below shows the religious affiliation of each of the justices sitting as of May 2019:

| Name | Religion | Appt. by | On the Court since |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Roberts (Chief Justice) | Roman Catholicism | G.W. Bush | 2005 |

| Clarence Thomas | Roman Catholicism | G.H.W. Bush | 1991 |

| Ruth Bader Ginsburg | Judaism | Clinton | 1993 |

| Stephen Breyer | Judaism | Clinton | 1994 |

| Samuel Alito | Roman Catholicism | G.W. Bush | 2006 |

| Sonia Sotomayor | Roman Catholicism | Obama | 2009 |

| Elena Kagan | Judaism | Obama | 2010 |

| Neil Gorsuch | Episcopalian, raised Roman Catholic[79][80] | Trump | 2017 |

| Brett Kavanaugh | Roman Catholicism | Trump | 2018 |

Protestant justices

Most Supreme Court justices have been Protestant Christians. These have included 33 Episcopalians, 18 Presbyterians, nine Unitarians, five Methodists, three Baptists, and lone representatives of various other denominations.[81] William Rehnquist was the Court's only Lutheran. Noah Swayne was a Quaker. Some 15 Protestant justices did not adhere to a particular denomination. The religious beliefs of James Wilson, one of the earliest Justices, have been the subject of some dispute, as there are writings from various points of his life from which it can be argued that he leaned towards Presbyterianism, Anglicanism, Thomism, or Deism; it has been deemed likely that he eventually favored some form of Christianity.[82] Baptist denominations and other evangelical churches have been underrepresented on the Court, relative to the population of the United States. Conversely, mainline Protestant churches historically were overrepresented.

Following the retirement of John Paul Stevens in June 2010, the Court had an entirely non-Protestant composition for the first time in its history.[83][84] Neil Gorsuch is the first member of a mainline Protestant denomination to sit on the court since Stevens' retirement.[85] Although Neil Gorsuch, appointed in 2017, attends and is a member of an Episcopal church, he was raised Catholic and it is unclear if he considers himself a Catholic who is also a member of a Protestant church or simply a Protestant.[79] Prior to his appointment he was an active member of Holy Comforter Episcopal Church and, then, St. John's Episcopal Church in Boulder, Colorado.[86][87]

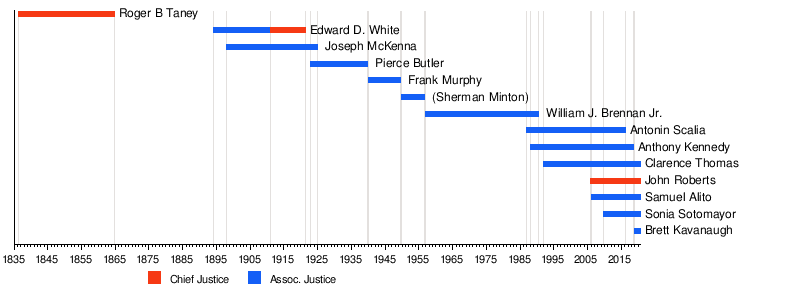

Catholic justices

The first Catholic justice, Roger B. Taney, was appointed chief justice in 1836 by Andrew Jackson. The second, Edward Douglass White, was appointed as an associate justice in 1894, but also went on to become chief justice. Joseph McKenna was appointed in 1898, placing two Catholics on the Court until White's death in 1921. This period marked the beginning of an inconsistently observed "tradition" of having a "Catholic seat" on the court.[88]

Other Catholic justices included Pierce Butler (appointed 1923) and Frank Murphy (appointed 1940). Sherman Minton, appointed in 1949, was a Protestant during his time on the Court. To some, however, his wife's Catholic faith implied a "Catholic seat".[89] Minton joined his wife's church in 1961, five years after he retired from the Court.[90] Minton was succeeded by a Catholic, however, when President Eisenhower appointed William J. Brennan to that seat. Eisenhower sought a Catholic to appoint to the Court—in part because there had been no Catholic justice since Murphy's death in 1949, and in part because Eisenhower was directly lobbied by Cardinal Francis Spellman of the Archdiocese of New York to make such an appointment.[91] Brennan was then the lone Catholic justice until the appointment of Antonin Scalia in 1986, and Anthony Kennedy in 1988.

Like Sherman Minton, Clarence Thomas was not a Catholic at the time he was appointed to the Court. Thomas was raised Catholic and briefly attended Conception Seminary College, a Roman Catholic seminary,[92] but had joined the Protestant denomination of his wife after their marriage. At some point in the late 1990s, Thomas returned to Catholicism. In 2005, John Roberts became the third Catholic Chief Justice and the fourth Catholic on the Court. Shortly thereafter, Samuel Alito became the fifth on the Court, and the eleventh in the history of the Court. Alito's appointment gave the Court a Catholic majority for the first time in its history. Besides Thomas, at least one other Justice, James F. Byrnes, was raised as a Roman Catholic, but converted to a different branch of Christianity prior to serving on the Court.

In contrast to historical patterns, the Court has gone from having a "Catholic seat" to being what some have characterized as a "Catholic court." The reasons for that are subject to debate, and are a matter of intense public scrutiny.[93] That the majority of the Court is now Catholic, and that the appointment of Catholics has become accepted, represents a historical 'sea change.' It has fostered accusations that the court has become "a Catholic boys club" (particularly as the Catholics chosen tend to be politically conservative) and calls for non-Catholics to be nominated.[94]

In May 2009, President Barack Obama nominated a Catholic woman, Sonia Sotomayor, to replace retiring Justice David Souter.[95] Her confirmation raised the number of Catholics on the Court to six, compared to three non-Catholics. With Antonin Scalia's death in February 2016, the number of Catholic Justices went back to five. Neil Gorsuch, appointed in 2017, was raised Catholic but attends and is a member of an Episcopal church; it is unclear if he identifies as a Catholic as well as belonging to the Episcopal Church.[79] With Anthony Kennedy's retirement in July 2018, the number of Catholic Justices went down by one, and returned to its previous number with the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh.

All of the Catholic justices have been members of the Roman (or Latin) rite within the Catholic Church.

| Name | State | Birth | Death | Year appointed |

Left office |

Appointed by | Reason for termination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roger B. Taney | Maryland | 1777 | 1864 | 1836 | 1864 | Jackson | death |

| Edward Douglass White | Louisiana | 1845 | 1921 | 1894 | 1921 | Cleveland (associate) Taft (chief)[96] | death |

| Joseph McKenna | California | 1843 | 1926 | 1898 | 1925 | McKinley | retirement |

| Pierce Butler | Minnesota | 1866 | 1939 | 1923 | 1939 | Harding | death |

| Frank Murphy | Michigan | 1890 | 1949 | 1940 | 1949 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| Sherman Minton | Indiana | 1890 | 1965 | 1949 | 1956 | Truman | death[97] |

| William J. Brennan, Jr. | New Jersey | 1906 | 1997 | 1956 | 1990 | Eisenhower | death[97] |

| Antonin Scalia | New Jersey | 1936 | 2016 | 1986 | 2016 | Reagan | death |

| Anthony Kennedy | California | 1936 | living | 1988 | 2018 | Reagan | retirement |

| Clarence Thomas | Georgia | 1948 | living | 1991 | incumbent | G. H. W. Bush | — |

| John Roberts | Maryland | 1955 | living | 2005 | incumbent | G. W. Bush | — |

| Samuel Alito | New Jersey | 1950 | living | 2006 | incumbent | G. W. Bush | — |

| Sonia Sotomayor | New York | 1954 | living | 2009 | incumbent | Obama | — |

| Brett Kavanaugh | Washington, D.C. | 1965 | living | 2018 | incumbent | Trump | — |

Graphical timeline of Catholic justices:

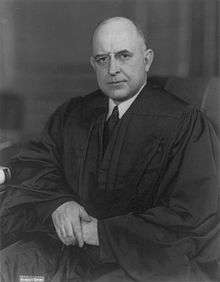

Jewish justices

In 1853, President Millard Fillmore offered to appoint Louisiana Senator Judah P. Benjamin to be the first Jewish justice, and The New York Times reported (on February 15, 1853) that "if the President nominates Benjamin, the Democrats are determined to confirm him". However, Benjamin declined the offer, and ultimately became Secretary of State for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The first Jewish nominee, Louis Brandeis, was appointed in 1916, after a tumultuous hearing process. The 1932 appointment of Benjamin Cardozo raised mild controversy for placing two Jewish justices on the Court at the same time, although the appointment was widely lauded based on Cardozo's qualifications, and the Senate was unanimous in confirming Cardozo.[98] Most Jewish Supreme Court justices were of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, with the exception of Cardozo, who was Sephardic. None of the Jewish Supreme Court Justices have practiced Orthodox Judaism while on the Court, although Abe Fortas was raised Orthodox.[99]

Cardozo was succeeded by another Jewish Justice, Felix Frankfurter, but Brandeis was succeeded by Protestant William O. Douglas. Negative reaction to the appointment of the early Jewish justices did not exclusively come from outside the Court. Justice James Clark McReynolds, a blatant anti-semite, refused to speak to Brandeis for three years following the latter's appointment and when Brandeis retired in 1939, did not sign the customary dedicatory letter sent to Court members on their retirement. During Benjamin Cardozo's swearing in ceremony McReynolds pointedly read a newspaper muttering "another one" and did not attend that of Felix Frankfurter, exclaiming "My God, another Jew on the Court!"[100]

Frankfurter was followed by Arthur Goldberg and Abe Fortas, each of whom filled what became known as the "Jewish Seat". After Fortas resigned in 1969, he was replaced by Protestant Harry Blackmun. No Jewish justices were nominated thereafter until Ronald Reagan nominated Douglas H. Ginsburg in 1987, to fill the vacancy created by the retirement of Lewis F. Powell; however, this nomination was withdrawn, and the Court remained without any Jewish justices until 1993, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg (unrelated to Douglas Ginsburg) was appointed to replace Byron White. Ginsburg was followed in relatively quick succession by the appointment of Stephen Breyer, also Jewish, in 1994 to replace Harry Blackmun. In 2010, the confirmation of President Barack Obama's nomination of Elena Kagan to the Court ensured that three Jewish justices would serve simultaneously. Prior to this confirmation, conservative political commentator Pat Buchanan stated that, "If Kagan is confirmed, Jews, who represent less than 2 percent of the U.S. population, will have 33 percent of the Supreme Court seats".[101] At the time of his remarks, 6.4 percent of justices had been Jewish in the history of the court.

| Name | State | Birth | Death | Year appointed |

Left office |

Appointed by | Reason for termination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Louis Brandeis | Kentucky | 1856 | 1941 | 1916 | 1939 | Wilson | retirement |

| Benjamin N. Cardozo | New York | 1870 | 1938 | 1932 | 1938 | Hoover | death |

| Felix Frankfurter | New York | 1882 | 1965 | 1939 | 1962 | F. Roosevelt | retirement |

| Arthur Goldberg | Illinois | 1908 | 1990 | 1962 | 1965 | Kennedy | resigned to become UN Ambassador |

| Abe Fortas | Tennessee | 1910 | 1982 | 1965 | 1969 | L.B. Johnson | resignation |

| Ruth Bader Ginsburg | New York | 1933 | living | 1993 | incumbent | Clinton | — |

| Stephen Breyer | California | 1938 | living | 1994 | incumbent | Clinton | — |

| Elena Kagan | New York | 1960 | living | 2010 | incumbent | Obama | — |

Graphical timeline of Jewish justices:

The shift to a Catholic majority, and non-Protestant Court

With Breyer's appointment in 1994, there were two Roman Catholic justices, Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy, and two Jewish justices, Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Clarence Thomas, who had been raised as a Roman Catholic but had attended an Episcopal church after his marriage, returned to Catholicism later in the 1990s. At this point, the four remaining Protestant justices—Rehnquist, Stevens, O'Connor, and Souter—remained a plurality on the Court, but for the first time in the history of the Court, Protestants were no longer an absolute majority.

The first Catholic plurality on the Court occurred in 2005, when Chief Justice Rehnquist was succeeded in office by Chief Justice John Roberts, who became the fourth sitting Catholic justice. On January 31, 2006, Samuel Alito became the fifth sitting Catholic justice, and on August 6, 2009, Sonia Sotomayor became the sixth. By contrast, there has been only one Catholic U.S. President, John F. Kennedy (unrelated to Justice Kennedy), and two Catholic U.S. Vice Presidents, Joe Biden and Mike Pence, and there has never been a Jewish U.S. President or Vice President.

At the beginning of 2010, Justice John Paul Stevens was the sole remaining Protestant on the Court.[95][102] In April 2010, Justice Stevens announced his retirement, effective as of the Court's 2010 summer recess. Upon Justice Stevens' retirement, which formally began on June 28, 2010, the Court lacked a Protestant member, marking the first time in its history that it was exclusively composed of Jewish and Catholic justices.[83] Although in January 2017, after seven years with no Protestant justices serving or nominated, President Donald Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to the Court, as noted above it is unclear whether Gorsuch considers himself a Catholic or an Episcopalian.[103][79] Following the retirement of Justice Kennedy, the Catholic majority on the Court was extended by the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh,[104] leaving five Catholic members of the Court, or six if Gorsuch is demarcated as a "Catholic."[79]

This development led to some comment. Law school professor Jeffrey Rosen wrote that "it's a fascinating truth that we've allowed religion to drop out of consideration on the Supreme Court, and right now, we have a Supreme Court that religiously at least, by no means looks like America".[105]

Unrepresented religions

A number of sizable religious groups, each less than 2% of the U.S. population,[106] have had no members appointed as justices. These include Orthodox Christians, Mormons, Pentecostals, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs. George Sutherland has been described as a "lapsed Mormon"[107] because he was raised in the LDS Church, his parents having immigrated to the United States during Sutherland's infancy to join that church.[108] Sutherland's parents soon left the LDS Church and moved to Montana.[108] Sutherland himself also disaffiliated with the faith, but remained in Utah and graduated from Brigham Young Academy in 1881, the only non-Mormon in his class.[109] In 1975, Attorney General Edward H. Levi had listed Dallin H. Oaks, a Mormon who had clerked for Earl Warren and was then president of Brigham Young University, as a potential nominee for Gerald Ford. Ford "crossed Oaks's name off the list early on, noting in the margin that a member of the LDS Church might bring a 'confirmation fight'".[110]

No professing atheist has ever been appointed to the Court, although some justices have declined to engage in religious activity, or affiliate with a denomination. As an adult, Benjamin Cardozo no longer practiced his faith and identified himself as an agnostic, though he remained proud of his Jewish heritage.[111]

Age

Unlike the offices of President, U.S. Representative, and U.S. Senator, there is no minimum age for Supreme Court justices set forth in the United States Constitution. However, justices tend to be appointed after having made significant achievements in law or politics, which excludes many young potential candidates from consideration. At the same time, justices appointed at too advanced an age will likely have short tenures on the Court.

The youngest justice ever appointed was Joseph Story, 32 at the time of his appointment in 1812; the oldest was Charles Evans Hughes, who was 67 at the time of his appointment as Chief Justice in 1930. (Hughes had previously been appointed to the Court as an associate justice in 1910, at the age of 48, but had resigned in 1916 to run for president). Story went on to serve for 33 years, while Hughes served 11 years after his second appointment. The oldest justice at the time of his initial appointment was Horace Lurton, 65 at the time of his appointment in 1909. Lurton died after only four years on the Court. The oldest sitting justice to be elevated to Chief Justice was Hughes' successor, Harlan Fiske Stone, who was 68 at the time of his elevation in 1941. Stone died in 1946, only five years after his elevation. The oldest nominee to the court was South Carolina senator William Smith, nominated in 1837, then aged around 75 (it is known that he was born in 1762, but not the exact date). The Senate confirmed Smith's nomination by a vote of 23–18, but Smith declined to serve.[112]

Of the justices currently sitting, the youngest at time of appointment was Clarence Thomas, who was 43 years old at the time of his confirmation in 1991. As of October 2019, Neil Gorsuch is the youngest justice sitting, at 52 years of age, while Ruth Bader Ginsburg is the oldest at 86 years. The oldest person to have served on the Court was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who stepped down two months shy of his 91st birthday.[113] John Paul Stevens, second only to Holmes,[113] left the court in June 2010, two months after turning 90.

The average age of the Court as a whole fluctuates over time with the departure of older justices and the appointment of younger people to fill their seats. The average age of the Court is 74 years, 6 months. Just prior to the death of Chief Justice Rehnquist in September 2005, the average age was 71. After Sonia Sotomayor was appointed in August 2009, the average age at which current justices were appointed was about 53 years old.

The longest period of time in which one group of justices has served together occurred from August 3, 1994, when Stephen Breyer was appointed to replace the retired Harry Blackmun, to September 3, 2005, the death of Rehnquist, totaling 11 years and 31 days. From 1789 until 1970, justices served an average of 14.9 years. Those who have stepped down since 1970 have served an average of 25.6 years. The retirement age had jumped from an average of 68 pre-1970 to 79 for justices retiring post-1970. Between 1789 and 1970 there was a vacancy on the Court once every 1.91 years. In the next 34 years since the two appointments in 1971, there was a vacancy on average only once every 3.75 years. The typical one-term president has had one appointment opportunity instead of two.[114]

Commentators have noted that advances in medical knowledge "have enormously increased the life expectancy of a mature person of an age likely to be considered for appointment to the Supreme Court".[115] Combined with the reduction in responsibilities carried out by modern justices as compared to the early justices, this results in much longer potential terms of service.[115] This has led to proposals such as imposing a mandatory retirement age for Supreme Court justices[116] and predetermined term limits.[117]

Educational background

Although the Constitution imposes no educational background requirements for federal judges, the work of the Court involves complex questions of law—ranging from constitutional law to administrative law to admiralty law—and consequently, a legal education has become a de facto prerequisite to appointment on the Supreme Court. Every person who has been nominated to the Court has been an attorney.[7]

Before the advent of modern law schools in the United States, justices, like most attorneys of the time, completed their legal studies by "reading law" (studying under and acting as an apprentice to more experienced attorneys) rather than attending a formal program. The first justice to be appointed who had attended an actual law school was Levi Woodbury, appointed to the Court in 1846. Woodbury had attended Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, the most prestigious law school in the United States in that day, prior to his admission to the bar in 1812. However, Woodbury did not earn a law degree. Woodbury's successor on the Court, Benjamin Robbins Curtis, who received his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1832, and was appointed to the Court in 1851, was the first Justice to bear such a credential.[118]

Associate Justice James F. Byrnes, whose short tenure lasted from June 1941 to October 1942, was the last justice without a law degree to be appointed; Stanley Forman Reed, who served on the Court from 1938 to 1957, was the last sitting justice from such a background. In total, of the 114 justices appointed to the Court, 48 have had law degrees, an additional 18 attended some law school but did not receive a degree, and 47 received their legal education without any law school attendance.[118] Two justices, Sherman Minton and Lewis F. Powell, Jr., earned a Master of Laws degree.[119]

The table below shows the college and law school from which each of the justices sitting as of October 2018 graduated:

Professional background

Not only have all justices been attorneys, nearly two thirds had previously been judges.[7] As of 2018, eight of the nine sitting justices previously served as judges of the United States Courts of Appeals, while Justice Elena Kagan served as Solicitor General, the attorney responsible for representing the federal government in cases before the Court. Few justices have a background as criminal defense lawyers, and Thurgood Marshall is reportedly the last justice to have had a client in a death penalty case.[120]

Historically, justices have come from some tradition of public service; only George Shiras, Jr. had no such experience.[121] Relatively few justices have been appointed from among members of Congress. Six were members of the United States Senate at the time of their appointment,[122][123] while one was a sitting member of the House of Representatives.[124] Six more had previously served in the Senate. Three have been sitting governors.[122][125] Only one, William Howard Taft, had been President of the United States.[126] The last justice to have held elected office was Sandra Day O'Connor, who was elected twice to the Arizona State Senate after being appointed there by the governor.

As of 2020, 42 justices have been military veterans.[127] Numerous justices were appointed who had served in the American Revolutionary War, the American Civil War (including three who had served in the Army of the Confederacy), World War I and World War II. However, no justice has been appointed who has served in any subsequent war. The last justice to have served in the military during wartime was John Paul Stevens, who was in naval intelligence during World War II.[128]

Predominantly, recent justices have had experience in the Executive branch. The last Member of Congress to be nominated was Sherman Minton. The last nominee to have any Legislative branch experience was Sandra Day O'Connor.

Financial means

The financial position of the typical Supreme Court Justice has been described as "upper-middle to high social status: reared in nonrural but not necessarily urban environment, member of a civic-minded, politically active, economically comfortable family".[118] Charles A. Beard, in his An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States, profiled those among the justices who were also drafters of the Constitution.

James Wilson, Beard notes, "developed a lucrative practice at Carlisle" before becoming "one of the directors of the Bank of North America on its incorporation in 1781".[129] A member of the Georgia Land Company, Wilson "held shares to the amount of at least one million acres".[130] John Blair was "one of the most respectable men in Virginia, both on account of his Family as well as fortune".[131] Another source notes that Blair "was a member of a prominent Virginia family. His father served on the Virginia Council and was for a time acting Royal governor. His granduncle, James Blair, was founder and first president of the College of William and Mary."[132] John Rutledge was elected Governor of South Carolina at a time when the Constitution of that state set, as a qualification for the office, ownership of "a settled plantation or freehold ... of the value of at least ten thousand pounds currency, clear of debt".[133] Oliver Ellsworth "rose rapidly to wealth and power in the bar of his native state" with "earnings... unrivalled in his own day and unexampled in the history of the colony", developing "a fortune which for the times and the country was quite uncommonly large".[134] Bushrod Washington was the nephew of George Washington, who was at the time of the younger Washington's appointment the immediate past President of the United States and one of the wealthiest men in the country.[135]

"About three-fifths of those named to the Supreme Court personally knew the President who nominated them".[91] There have been exceptions to the typical portrait of justices growing up middle class or wealthy. For example, the family of Sherman Minton went through a period of impoverishment during his childhood, resulting from the disability of his father due to a heat stroke.[136]

In 2008, seven of the nine sitting justices were millionaires, and the remaining two were close to that level of wealth.[137] Historian Howard Zinn, in his 1980 book A People's History of the United States, argues that the justices cannot be neutral in matters between rich and poor, as they are almost always from the upper class.[138] Chief Justice Roberts is the son of an executive with Bethlehem Steel; Justice Stevens was born into a wealthy Chicago family;[139] and Justices Kennedy and Breyer both had fathers who were successful attorneys. Justices Alito and Scalia both had educated (and education-minded) parents: Scalia's father was a highly educated college professor and Alito's father was a high school teacher before becoming "a long-time employee of the New Jersey state legislature".[140] Only Justices Thomas and Sotomayor have been regarded as coming from a lower-class background. One authority states that "Thomas grew up in poverty. The Pin Point community he lived in lacked a sewage system and paved roads. Its inhabitants dwelled in destitution and earned but a few cents each day performing manual labor".[141] The depth of Thomas' poverty has been disputed by suggestions of "ample evidence to suggest that Thomas enjoyed, by and large, a middle-class upbringing".[142]

Financial disclosures

Beginning in 1979, the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 required federal officials, including the justices, to file annual disclosures of their income and assets.[143] These disclosures provide a snapshot into the wealth of the justices, reported within broad ranges, from year to year since 1979. In the first such set of disclosures, only two justices were revealed to be millionaires: Potter Stewart[144] and Lewis F. Powell,[145] with Chief Justice Warren Burger coming in third with about $600,000 in holdings.[144] The least wealthy Justice was Thurgood Marshall.[144]

The 1982 report disclosed that newly appointed Justice Sandra Day O'Connor was a millionaire, and the second-wealthiest Justice on the Court (after Powell).[146] The remaining justices listed assets in the range of tens of thousands to a few hundred-thousand, with the exception of Thurgood Marshall, who "reported no assets or investment income of more than $100".[146] The 1985 report had the justices in relatively the same positions,[147] while the 1992 report had O'Connor as the wealthiest member of the Court, with Stevens being the only other millionaire, most other justices reporting assets averaging around a half million dollars, and the two newest justices, Clarence Thomas and David Souter, reporting assets of at least $65,000.[148] (In 2011, however, it was revealed that Thomas had misstated his income going back to at least 1989.[149][150][151])

The 2007 report was the first to reflect the holdings of John Roberts and Samuel Alito. Disclosures for that year indicated that Clarence Thomas and Anthony Kennedy were the only justices who were clearly not millionaires, although Thomas was reported to have signed a book deal worth over one million dollars.[152] Other justices have reported holdings within the following ranges:[153][154]

| Justice | Lowest range | Highest range |

| John Roberts | $2,400,000 | $6,200,000 |

| John Paul Stevens | $1,100,000 | $3,500,000 |

| Anthony Kennedy | $365,000 | $765,000 |

| David Souter | ? | ? |

| Clarence Thomas | $150,000 | $410,000 |

| Ruth Bader Ginsburg | $5,000,000 | $25,000,000 |

| Stephen Breyer | $4,900,000 | $16,800,000 |

| Samuel Alito | $770,000 | $2,000,000 |

| Neil Gorsuch | $3,200,000 | $7,300,000 |

The financial disclosures indicate that many of the justices have substantial stock holdings.[152] This, in turn, has affected the business of the Court, as these holdings have led justices to recuse themselves from cases, occasionally with substantial impact. For example, in 2008, the recusal of John Roberts in one case, and Samuel Alito in another, resulted in each ending in a 4–4 split, which does not create a binding precedent.[155] The Court was unable to decide another case in 2008 because four of the nine justices had conflicts, three arising from stock ownership in affected companies.[156]

See also

- Ideological leanings of United States Supreme Court justices

- List of United States Supreme Court Justices who also served in Congress

- List of law schools attended by United States Supreme Court Justices

Notes

- David Josiah Brewer from Kansas; Byron White and Neil Gorsuch from Colorado; Willis Van Devanter from Wyoming; George Sutherland from Utah and Sandra Day O'Connor and William Rehnquist from Arizona

- West Virginia could be argued to have produced no Supreme Court Justices back to the inaugural Court – it was part of Virginia between 1788 and 1863, and none of Virginia’s five antebellum Supreme Court Justices hailed from what became West Virginia.

References

- Segal and Spaeth (2002). The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. p. 183.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. p. 46.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. p. 54.

- John P. McIver, Department of Political Science, University of Colorado, Boulder Review of A "REPRESENTATIVE" SUPREME COURT? THE IMPACT OF RACE, RELIGION, AND GENDER ON APPOINTMENTS by Barbara A. Perry. Archived October 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- See also Kreimendahl, Ilka (2002) Appointment and Nomination of Supreme Court Justices (Scholarly Paper, Advanced Seminar), Amerikanische Entwicklung im Spiegel ausgewählter Entscheidungen des Supreme Court, University of Kassel 32 pages.

- Marshall (2008). Public Opinion and the Rehnquist Court. p. 109.

- Segal and Spaeth (2002). The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. p. 182.

- Marshall (2008). Public Opinion and the Rehnquist Court. p. 108.

- Segal and Spaeth (2002), quoting Richard Friedman, "The Transformation in Senate Response to Supreme Court Nominations", 5 Cardozo Law Review 1 (1983), p. 50.

- Segal and Spaeth (2002). The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. pp. 182–83.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. pp. 46–47.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. p. 47.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. p. 48.

- Mark Sherman, Is Supreme Court in need of regional diversity? (May 1, 2010).

- Kermit Hall, James W. Ely, Joel B. Grossman, The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (2005), p. 710; all other foreign born justices were born in English-speaking countries, except Brewer, who moved from Turkey to the United States while still in his infancy.

- McAllister, Stephen R. (Autumn 2015). "The Kansas Justice, David Josiah Brewer" (PDF). The Green Bag. 19 (1): 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". Supreme Court of the United States. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- John Richard Schmidhauser, Judges and justices: the Federal Appellate Judiciary (1979), p. 60.

- Kaufman, Andrew L. (1998). "1. Cardozo's Heritage: The Sephardim and Tammany Hall". Cardozo (First ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674096452. Retrieved June 18, 2017 – via The New York Times.

The family into which Benjamin Nathan Cardozo was born ... was a Sephardic family, descended from those Jews who had fled from the Iberian peninsula during the Inquisition and had come to America via the Netherlands and England. Both branches of the family (the Cardozos and the Nathans) had arrived in the American colonies before the American Revolution. Cardozo family tradition holds that their ancestors were Portuguese Marranos--Jews who practiced Judaism secretly after forced conversion to Christianity--who fled the Inquisition in the seventeenth century. They took refuge first in Holland and then in London. Later members of the family emigrated to the New World. Aaron Cardozo, was the first Cardozo to settle in the American colonies, arriving in New York from London in 1752.

- Biskupic, Joan (2009), "Passions of his mind", in Biskupic, Joan (ed.), American original: the life and constitution of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, New York: Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus And Giroux, pp. 11–15, ISBN 9780374202897.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Preview.

- Walthr, Matthew (April 21, 2014). "Sam Alito: A Civil Man". The American Spectator. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017 – via The ANNOTICO Reports.

- DeMarco, Megan (February 14, 2008). "Growing up Italian in Jersey: Alito reflects on ethnic heritage". The Times of Trenton, New Jersey. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Halberstam, Malvina (March 1, 2009). "Ruth Bader Ginsburg". Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Sheldon Goldman, Picking Federal Judges: Lower Court Selection from Roosevelt Through Reagan (1999), p. 184-85. ISBN 0-300-08073-5

- "What Negroes can expect from Kennedy", Ebony Magazine(Jan 1961), v. 16, no. 3, p. 33.

- Graham, Fred P. (August 31, 1967) Senate Confirms Marshall As the First Negro Justice; 10 Southerners Oppose High Court Nominee in 69-to-11 Vote. The New York Times.

- According to the Social Security Administration Popular baby name database, Thurgood has never been in the top 1000 of male baby names.

- Jan Crawford Greenburg (September 30, 2007). "Clarence Thomas: A Silent Justice Speaks Out". ABC News. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- Davis (2005). Electing Justice: Fixing the Supreme Court Nomination Process. p. 50.

- Dowd, Maureen. "The Supreme Court; Conservative black judge, Clarence Thomas, is named to Marshall's court seat", The New York Times, July 2, 1991.

- Schwartz (2004). Right Wing Justice: The Conservative Campaign to Take Over the Courts. p. 112.

- George Stephanopoulos, All Too Human: A Political Education (Back Bay Books, 2000).

- Gwen Ifill, White House Memo; Mitchell's Rebuff Touches Off Scramble for Court Nominee, N.Y. Times (April 16, 1994).

- Kirkpatrick, David D. Senate Democrats Are Shifting Focus From Roberts to Other Seat, The New York Times, September 9, 2005.

- Specter: Gonzales Not Ready for Supreme Court Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Capitol Hill Blue, September 12, 2005.

- Kirkpatrick, David D.; Stolberg, Sheryl (September 20, 2005). "White House Said to Shift List for 2nd Court Seat". The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- Mauro, Tony (December 1, 2008). "Pressure Is on Obama to Name First Hispanic Supreme Court Justice". Legal Times.

- Obama picks Sotomayor for Supreme Court, MSNBC (May 26, 2009).

- Neil A. Lewis, Was a Hispanic Justice on the Court in the ’30s?, The New York Times, May 26, 2009.

- Cardozo was first, but was he Hispanic? USA Today May 26, 2009

- "Distinguished Americans & Canadians of Portuguese Descent". Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- National Hispanic Center for Advanced Studies and Policy Analysis (U.S.), The State of Hispanic America (1982), p. 98.

- Nicolás Kanellos, The Hispanic American Almanac (1996), p. 302.

- F. Arturo Rosales, The Dictionary of Latino Civil Rights History, Arte Publico Press (February 28, 2007). p 59

- Mark Sherman, First Hispanic justice? Some say it was Cardozo, The Associated Press, 2009.

- Robert Schlesinger, Would Sotomayor be the First Hispanic Supreme Court Justice or Was it Cardozo? US News & World Report May 29, 2009 Archived May 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Mark Sherman, First Hispanic justice? Some say it was Cardozo, Fox News, (May 26, 2009).

- Aviva Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History (2009), p. 86.

- Richard Polenberg, The World of Benjamin Cardozo: Personal Values and the Judicial Process (1999), p. 88.

- Taranto, James. "Justice Dinh". Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- Susan Montoya Bryan, American Indians ask for voice on federal court Archived July 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press (July 2, 2010).

- Flores, Reena (September 23, 2016). "Donald Trump will expand list of possible Supreme Court picks". CBS News. Retrieved September 23, 2016 – via MSN.

- "Donald J. Trump Finalizes List of Potential Supreme Court Justice PicksS". www.donaldjtrump.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Roberts, John. "Trump completes interviews of Supreme Court candidates, short-list down to 6". Fox News. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Savage, David (July 3, 2018). "Judge Amy Coney Barrett, a potential Supreme Court nominee, has defended overturning precedents". LA Times. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

Judge Brett Kavanaugh, 53, a Washington veteran who serves on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and Barrett, 46, have been seen as the front-runners. White House advisors say Judges Thomas Hardiman from Pennsylvania, Raymond Kethledge from Michigan and Amul Thapar from Kentucky are also top candidates from Trump’s previously announced list of 25 judges, legal scholars and politicians.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. p. 53.

- Hook, Janet (August 7, 2010). "Elena Kagan Sworn in as Supreme Court Justice". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- Maltese (1998). The Selling of Supreme Court Nominees. p. 126.

- Salokar and Volcansek (1996). Women in Law: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. p. 20.

- Argetsinger, Amy; Roberts, Roxanne (May 27, 2009). "Sotomayor: A Single Supreme?". The Washington Post. The Reliable Source. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- "Kagan bucks 40-year trend as court pick", Reuters News, May 10, 2010.

- Lisa Belkin, "Judging Women", The New York Times Magazine (May 18, 2010).

- Flanders, Henry (1874) [1874]. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. 1. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- White, Edward G. (2006). Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. p. 131.

- "Natalie Cornell Rehnquist". Arlingtoncemetery.net. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- "Husband of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dies". The Washington Post. June 27, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- Murdoch and Price (2002). Courting Justice: Gay Men and Lesbians V. the Supreme Court. p. 187.

- Stern, Keith (2006). Queers in History. p. 84. Stating of Carswell, "He's the only known homosexual to have been nominated to the Supreme Court, though he was in the closet".

- Dean (2001). The Rehnquist Choice: The Untold Story of the Nixon Appointment That Redefined the Supreme Court. p. 20.

- Joyce Murdoch and Deb Price, Courting Justice: Gay Men and Lesbians v. The Supreme Court (New York: Basic Books, 2001) p.18.

- Joyce Murdoch and Deb Price, Courting Justice: Gay Men and Lesbians v. The Supreme Court (New York: Basic Books, 2001) pp. 19-20.

- Quoted in Joyce Murdoch and Deb Price, Courting Justice: Gay Men and Lesbians v. The Supreme Court (New York: Basic Books, 2001) p.19.

- Jeffrey Rosen, NYT November 2, 1997

- Kaufman (1998). Cardozo. p. 68.

- Kaufman (1998). Cardozo. pp. 68–69.

- Tinsley E. Yarbrough, "David Hackett Souter: Traditional Republican on the Rehnquist Court" (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. viii.

- Baird, Julia (May 12, 2010). "From softball to Bridget Jones: Why we should stop talking about Elena Kagan's sexuality". Newsweek. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- Ruth Marcus, Elena Kagan: A smart woman with fewer choices?, The Washington Post (Friday, May 14, 2010).

- Daniel Burke (March 22, 2017). "What is Neil Gorsuch's religion? It's complicated". CNN.com.

Springer said she doesn't know whether Gorsuch considers himself a Catholic or an Episcopalian. "I have no evidence that Judge Gorsuch considers himself an Episcopalian, and likewise no evidence that he does not." Gorsuch's younger brother, J.J., said he too has "no idea how he would fill out a form. He was raised in the Catholic Church and confirmed in the Catholic Church as an adolescent, but he has been attending Episcopal services for the past 15 or so years."

- "What Neil Gorsuch's faith and writings could say about his approach to religion on the Supreme Court". The Denver Post. February 10, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Adherents.com page on the Supreme Court.

- Mark D. Hall, "James Wilson: Presbyterian, Anglican, Thomist, or Deist? Does it Matter?", in Daniel L. Dreisbach, Mark David Hall, Jeffrey Morrison, Jeffry H. Morrison, eds., The Founders on God and Government (2004). p. 181, 184-195.

- Nina Totenberg, "Supreme Court May Soon Lack Protestant Justices," NPR, Heard on Morning Edition, April 7, 2010, found at NPR website and transcript found at NPR website. Cited by Sarah Pulliam Bailey, "The Post-Protestant Supreme Court: Christians weigh in on whether it matters that the high court will likely lack Protestant representation," Christianity Today, April 10, 2010, found at Christianity Today website. Also cited by "Does the U.S. Supreme Court need another Protestant?" USA Today, April 9, 2010, found at USA Today website. All accessed April 10, 2010.

- Richard W. Garnett, "The Minority Court", The Wall Street Journal (April 17, 2010), W3.

- "Neil Gorsuch belongs to a notably liberal church — and would be the first Protestant on the Court in years". Washington Post. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Editor, Daniel Burke, CNN Religion. "What is Neil Gorsuch's religion? It's complicated". CNN. Retrieved October 11, 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Supreme Court nominee Gorsuch: An Episcopal faith?". Episcopal Cafe. February 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Hitchcock, James, Catholics and the Supreme Court: An Uneasy Relationship (June 2004) (from Catalyst (magazine)).

- Associated Press (September 15, 1949). "Indiana Man Is Nominated for U.S. Court Post". Kentucky New Era.

- Religious affiliation of Supreme Court justices Justice Sherman Minton converted to Catholicism after his retirement. James F. Byrnes was raised as Catholic, but became an Episcopalian before his confirmation as a Supreme Court Justice.

- Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold J. Spaeth, The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited (2002) p. 184.

- Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas visits Conception Seminary College Archived March 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Winter 2001.

- Perry, Barbara A. "Catholics and the Supreme Court: From the 'Catholic Seat' to the New Majority," in Catholics and Politics: The Dynamic Tension between Faith and Power, Georgetown University Press, 2008, Edited by K. E. Heyer, M. J. Rozell, M. A. Genovese.

- Kissling, Frances (May 17, 2009) Catholic Boy's Club: Religion and the Supreme Court Religious Dispatches. Frances Kissling is a visiting scholar at the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania and former president of Catholics for a Free Choice.

- Paulson, Michael Catholicism: Sotomayor would be sixth Catholic May 26, 2009. Boston Globe.

- This individual was elevated from Associate Justice to Chief Justice. Unlike the inferior courts, the Chief Justice is separately nominated and subject to a separate confirmation process, regardless of whether or not (s)he is already an Associate Justice.

- Deaths in senior status seem to cause confusion. There are two types of retirement: in the first type, the justice resigns his appointment in return for a pension, and the "Reason Appointment Terminated" is marked as "retirement". In the second type of retirement, called senior status, the justice's appointment does not end. Instead, the justice accepts a reduced workload on an inferior court. For instance, Stanley F. Reed was frequently assigned to the Court of Claims when he was in senior status. As of 2006, every justice except Charles Evans Whittaker who has assumed senior status has died in it; in that case, the judge will have the "Reason Appointment Terminated" as "death", even though they retired from the court before they died.

- The New York Times, February 25, 1932, p. 1.

- Singer, Saul Jay (October 17, 2018). "Abe Fortas and Nixon's 'Franking' Privilege". The Jewish Press. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

Although raised Orthodox, Fortas was himself not observant, to the point that he married a Protestant; as Professor David Dalin writes, “[F]or Fortas, his parents’ Judaism was always an obstacle to be overcome rather than a heritage to be celebrated.

- Henry Julian Abraham, Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II (2007), p. 140.

- Guthrie, Marisa (February 16, 2012). "Pat Buchanan Officially Out at MSNBC". The Hollywood Reporter.

- Goodstein, Laurie (May 30, 2009). "Sotomayor Would Be Sixth Catholic Justice, but the Pigeonholing Ends There". The New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- Robert Barnes, Trump picks Colo. appeals court judge Neil Gorsuch for Supreme Court, The Washington Post (January 31, 2017).

- "Five things to know about Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh". USA Today. July 9, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Rosen, Jeffrey. The Supreme Court: The Personalities and Rivalries That Defined America. Times Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8050-8182-4"

- Pew Research Religious Landscape Survey Retrieved April 5, 2015

- Dean L. May, Utah: a People's History (1987), p. 162.

- Robert R. Mayer, The Court and the American crises, 1930–1952 (1987), p. 217.

- Eric Alden Eliason, Mormons and Mormonism: an Introduction to an American World Religion (2001), p. 169.

- David Alistair Yalof, Pursuit of Justices: Presidential Politics and the Selection of Supreme Court Nominees (2001), p. 128.

- Jewish Virtual Library, Benjamin Cardozo.

- Steven P. Brown, John McKinley and the Antebellum Supreme Court (2012), p. 106.

- Weiss, Debra Cassens (November 19, 2007). "John Paul Stevens Second-Oldest Justice Ever". ABA Journal. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Steven G. Calabresi and James Lindgren, Justice for Life? The case for Supreme Court term limits., The Wall Street Journal, April 10, 2005.

- Roger C. Cramton and Paul D. Carrington, eds., Reforming the Court: Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices (Carolina Academic Press, 2006), p. 4.

- Richard Epstein, "Mandatory Retirement for Supreme Court Justices", in Roger C. Cramton and Paul D. Carrington, eds., Reforming the Court: Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices (Carolina Academic Press, 2006), p. 415.

- Arthur D. Hellman, "Reining in the Supreme Court: Are Term Limits the Answer?", in Roger C. Cramton and Paul D. Carrington, eds., Reforming the Court: Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices (Carolina Academic Press, 2006), p. 291.

- Henry Julian Abraham, Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II (2007), p. 49.

- Biographical encyclopedia of the Supreme Court : the lives and legal philosophies of the justices / edited by Melvin I. Urofsky. Washington, D.C. : CQ Press, c2006.

- Ifill, Sherrilyn (May 4, 2009). "Commentary: Break the mold for Supreme Court picks". CNN. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Abraham (2007), p. 48.

- O'Brien (2003). Storm Center. p. 34.

- U.S. Senate, Senators Who Served on the U.S. Supreme Court (accessed May 12, 2009).

- U.S. Congress, House Members Who Became Members of the U.S. Supreme Court Archived March 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (accessed May 12, 2009).

- Abraham (2007), p. 49.

- Anderson (1980), p. 184.

- Riley-Topping, Rory E. (September 25, 2018). "More veterans should be nominated to the Supreme Court". The Hill.

- Cohen, Andrew (August 13, 2012). "None of the Supreme Court Justices Has Battle Experience". The Atlantic.

- Beard (1913). An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. p. 147.

- Beard (1913). An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. p. 148.

- Beard (1913). An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. p. 77.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History page on John Blair.

- Beard (1913). An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. p. 142.

- Beard (1913). An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. p. 89.

- Eugene Parsons, Graeme Mercer Adam and Henry Wade Rogers, George Washington: A Character Sketch, (1903), p. 34.

- Gugin, Linda; St. Clair, James E. (1997). Sherman Minton: New Deal Senator, Cold War Justice. Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 0-87195-116-9.

- Justices are well-off, well-traveled, CNN, June 4, 2008.

- Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (New York: Perennial, 2003), p.260-261 ISBN 0-06-052837-0.

- Jeffrey Rosen, "The Dissenter," The New York Times Magazine (September 23, 2007).

- Oyez Biography of Samuel A. Alito, Jr..

- Oyez Biography of Clarence Thomas.

- Christopher Alan Bracey, Saviors Or Sellouts: The Promise and Peril of Black Conservatism (2008), p. 152 (stating of Thomas: "He is a man who claims to have risen from boyhood poverty, but there is ample evidence to suggest that Thomas enjoyed, by and large, a middle-class upbringing").

- The constitutionally of those portions of the Act requiring federal judges to disclose their income and assets were themselves challenged in a United States federal court, and were held to be constitutional. Duplantier v. United States, 606 F.2d 654 (5th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 1076 (1981).

- Melinda Beck et al., "Who Has How Much in Washington", Newsweek (May 28, 1979), p. 40.

- "Powell Reports Finances", Facts on File World News Digest (June 22, 1979), p. 464 B3.

- Barbara Rosewicz, "Millionaires on the bench", United Press International (May 17, 1982), Washington News.

- Henry J. Reske, "Justices reveal personal worth", United Press International (May 16, 1985), Washington News.

- "Souter and Thomas Report Least Assets of All Justices", The New York Times (May 17, 1992), Section 1; Page 31; Column 1; National Desk

- Geiger, Kim (January 22, 2011). "Clarence Thomas failed to report wife's income, watchdog says". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- Lichtblau, Eric (January 24, 2011). "Thomas Cites Failure to Disclose Wife's Job". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- Camia, Catalina (January 24, 2011). "Clarence Thomas fixes reports to include wife's pay". USA Today. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- "Justices report 2006 finances", AFX News Limited (June 8, 2007).

- Justices of the Supreme Court, MoneyLine Reference (accessed January 18, 2006).

- Ashley Balcerzak and Viveca Novak, "Trump’s pick: Gorsuch is respected jurist — and another multimillionaire", OpenSecrets.org, Center for Responsive Politics (January 31, 2017).

- "Supreme Recusal; When high court justices step aside from cases, there is no easy remedy for the consequences", The Washington Post (March 8, 2008), p. A14.