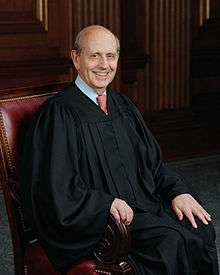

Stephen Breyer

Stephen Gerald Breyer (/ˈbraɪ.ər/; born August 15, 1938) is an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. A lawyer by occupation, he became a professor and jurist before President Bill Clinton appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1994; Breyer is generally associated with its more liberal side.[1]

Stephen Breyer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Assumed office August 3, 1994 | |

| Nominated by | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Harry Blackmun |

| Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit | |

| In office March 1990 – August 3, 1994 | |

| Preceded by | Levin H. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Juan R. Torruella |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit | |

| In office December 10, 1980 – August 3, 1994 | |

| Nominated by | Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Sandra Lynch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Stephen Gerald Breyer August 15, 1938 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Joanna Hare (m. 1967) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Charles Breyer (brother) |

| Education | Stanford University (BA) Magdalen College, Oxford (BA) Harvard University (LLB) |

After a clerkship with Supreme Court Associate Justice Arthur Goldberg in 1964, Breyer became well-known as a law professor and lecturer at Harvard Law School, starting in 1967. There he specialized in administrative law, writing a number of influential textbooks that remain in use today. He held other prominent positions before being nominated for the Supreme Court, including special assistant to the United States Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust and assistant special prosecutor on the Watergate Special Prosecution Force in 1973. He also served on the First Circuit Court of Appeals from 1980 to 1994.

In his 2005 book Active Liberty, Breyer made his first attempt to systematically lay out his views on legal theory, arguing that the judiciary should seek to resolve issues in a manner that encourages popular participation in governmental decisions.

Early life and education

Breyer was born on August 15, 1938, in San Francisco, California,[2] the son of Anne A. (née Roberts) and Irving Gerald Breyer,[3] and raised in a middle-class Jewish family. Irving Breyer was legal counsel for the San Francisco Board of Education.[4] Stephen Breyer and his younger brother, Charles, a federal district judge, are both Eagle Scouts of San Francisco's Troop 14.[5][6] Breyer's paternal great-grandfather emigrated from Romania to the United States, settling in Cleveland, where Breyer's grandfather was born.[7] Breyer graduated from Lowell High School in 1955. At Lowell, he was a member of the Lowell Forensic Society and debated regularly in high school tournaments, including against future California governor Jerry Brown and future Harvard Law School professor Laurence Tribe.[8]

After high school, Breyer attended Stanford University, where he majored in philosophy and graduated in 1959 with a Bachelor of Arts degree with honors.[9] He was awarded a Marshall Scholarship which he used to study philosophy, politics, and economics at Magdalen College, Oxford.[10] He then returned to the United States to attend Harvard Law School, where he was a member of the Harvard Law Review and graduated in 1964 with a Bachelor of Laws degree magna cum laude.[11]

In 1967, Breyer married Joanna Freda Hare, a psychologist and member of the British aristocracy, the youngest daughter of John Hare, 1st Viscount Blakenham. They have three adult children: Chloe, an Episcopal priest and author of The Close; Nell; and Michael.[12]

Legal career

Breyer served as a law clerk to Associate Justice Arthur Goldberg during the 1964 term (list), and served briefly as a fact-checker for the Warren Commission. He worked in the U.S. Department of Justice's Antitrust Division as a special assistant to its Assistant Attorney General from 1965 to 1967, and an assistant special prosecutor on the Watergate Special Prosecution Force in 1973. Breyer was a special counsel to the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary from 1974 to 1975 and served as chief counsel of the committee from 1979 to 1980.[12] He worked closely with the chairman of the committee, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, to pass the Airline Deregulation Act that closed the Civil Aeronautics Board.[8][13]

Breyer was a lecturer, assistant professor, and law professor at Harvard Law School starting in 1967. He was a professor at Harvard Law until 1980, and held a joint appointment at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government from 1977 to 1980. At Harvard, Breyer was known as a leading expert on administrative law.[14] While there, he wrote two highly influential books on deregulation: Breaking the Vicious Circle: Toward Effective Risk Regulation and Regulation and Its Reform. In 1970, Breyer wrote "The Uneasy Case for Copyright", one of the most widely cited skeptical examinations of copyright. Breyer was a visiting professor at the College of Law in Sydney, Australia, the University of Rome,[12] and the Tulane University Law School.[15]

Judicial career

U.S. Court of Appeals (1980–1994)

In the last days of President Jimmy Carter's administration, on November 13, 1980, Carter nominated Breyer to the First Circuit, to a new seat established by 92 Stat. 1629, and the United States Senate confirmed him on December 9, 1980, by an 80–10 vote.[17] He received his commission on December 10, 1980. From 1980 to 1994, Breyer was a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit; he was the court's Chief Judge from 1990 to 1994.[12] One of his duties as chief judge was to oversee the design and construction of a new federal courthouse for Boston, beginning an avocational interest in architecture and the Pritzker Architecture Prize.[18]

Breyer served as a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States between 1990 and 1994 and the United States Sentencing Commission between 1985 and 1989.[12] On the sentencing commission he played a key role in reforming federal criminal sentencing procedures, producing the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which were formulated to increase uniformity in sentencing.[19]

Breyer's service on the First Circuit terminated on August 2, 1994, upon his elevation to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court (1994–present)

In 1993, President Bill Clinton considered him for the seat vacated by Byron White that ultimately went to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[20] Breyer's appointment came shortly thereafter, however, following the retirement of Harry Blackmun in 1994, when Clinton nominated Breyer as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on May 17, 1994. Breyer was confirmed by the Senate on July 29, 1994, by an 87 to 9 vote, and received his commission on August 3.[12] He was the second-longest-serving junior justice in the history of the Court, close to surpassing the record set by Justice Joseph Story of 4,228 days (from February 3, 1812, to September 1, 1823); Breyer fell 29 days short of tying this record, which he would have reached on March 1, 2006, had Justice Samuel Alito not joined the Court on January 31, 2006.

Judicial philosophy

In general

Breyer's pragmatic approach to the law "will tend to make the law more sensible", according to Cass Sunstein, who added that Breyer's "attack on originalism is powerful and convincing".[21] In 2006, Breyer said that in assessing a law's constitutionality, while some of his colleagues "emphasize language, a more literal reading of the [Constitution's] text, history and tradition", he looks more closely to the "purpose and consequences".[22]

Breyer has consistently voted in favor of abortion rights,[23][24] one of the most controversial areas of the Supreme Court's docket. He has also defended the Court's use of foreign law and international law as persuasive (but not binding) authority in its decisions.[25][26][27] Breyer is also recognized to be deferential to the interests of law enforcement and to legislative judgments in the Court's First Amendment rulings. He has demonstrated a consistent pattern of deference to Congress, voting to overturn congressional legislation at a lower rate than any other Justice since 1994.[28]

Breyer's extensive experience in administrative law is accompanied by his staunch defense of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. Breyer rejects the strict interpretation of the Sixth Amendment espoused by Justice Scalia that all facts necessary to criminal punishment must be submitted to a jury and proved beyond a reasonable doubt.[29] In many other areas on the Court, too, Breyer's pragmatism was considered the intellectual counterweight to Scalia's textualist philosophy.[30]

In describing his interpretive philosophy, Breyer has sometimes noted his use of six interpretive tools: text, history, tradition, precedent, the purpose of a statute, and the consequences of competing interpretations.[31] He has noted that only the last two differentiate him from textualists such as Scalia. Breyer argues that these sources are necessary, however, and in the former case (purpose), can in fact provide greater objectivity in legal interpretation than looking merely at what is often ambiguous statutory text.[32] With the latter (consequences), Breyer argues that considering the impact of legal interpretations is a further way of ensuring consistency with a law's intended purpose.[33]

Court clerks described him as the "most effective emissary to the Court's right wing".[34]

Active Liberty

Breyer expounded his judicial philosophy in 2005 in Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution. In it, Breyer urges judges to interpret legal provisions (of the Constitution or of statutes) in light of the purpose of the text and how well the consequences of specific rulings fit those purposes. The book is considered a response to the 1997 book A Matter of Interpretation, in which Antonin Scalia emphasized adherence to the original meaning of the text alone.[23][35]

In Active Liberty, Breyer argues that the Framers of the Constitution sought to establish a democratic government involving the maximum liberty for its citizens. Breyer refers to Isaiah Berlin’s Two Concepts of Liberty. The first Berlinian concept, being what most people understand by liberty, is "freedom from government coercion". Berlin termed this "negative liberty" and warned against its diminution; Breyer calls this "modern liberty". The second Berlinian concept – "positive liberty" – is the "freedom to participate in the government". In Breyer's terminology, this is the "active liberty" the judge should champion. Having established what "active liberty" is, and positing the primary importance (to the Framers) of this concept over the competing idea of "negative liberty", Breyer makes a predominantly utilitarian case for rulings that give effect to the democratic intentions of the Constitution.

The book's historical premises and practical prescriptions have been challenged. For example, according to Peter Berkowitz,[36] the reason that "[t]he primarily democratic nature of the Constitution's governmental structure has not always seemed obvious", as Breyer puts it, is "because it's not true, at least in Breyer's sense, that the Constitution elevates active liberty above modern [negative] liberty". Breyer's position "demonstrates not fidelity to the Constitution", Berkowitz argues, "but rather a determination to rewrite the Constitution's priorities". Berkowitz suggests that Breyer is also inconsistent in failing to apply this standard to the issue of abortion, instead preferring decisions "that protect women's modern liberty, which remove controversial issues from democratic discourse". Failing to answer the textualist charge that the Living Documentarian judge is a law unto himself, Berkowitz argues that Active Liberty "suggests that when necessary, instead of choosing the consequence that serves what he regards as the Constitution's leading purpose, Breyer will determine the Constitution’s leading purpose on the basis of the consequence that he prefers to vindicate".

Against the last charge, Cass Sunstein has defended Breyer, noting that of the nine justices on the Rehnquist Court, Breyer had the highest percentage of votes to uphold acts of Congress and also to defer to the decision of the executive branch.[37] However, according to Jeffrey Toobin in The New Yorker, "Breyer concedes that a judicial approach based on 'active liberty' will not yield solutions to every constitutional debate", and that, in Breyer's words, "respecting the democratic process does not mean you abdicate your role of enforcing the limits in the Constitution, whether in the Bill of Rights or in separation of powers."[9]

To this point, and from a discussion at the New York Historical Society in March 2006, Breyer has noted that "democratic means" did not bring about an end to slavery, or the concept of "one man, one vote", which allowed corrupt and discriminatory (but democratically inspired) state laws to be overturned in favor of civil rights.[38]

Other books

In 2010, Breyer published a second book, Making Our Democracy Work: A Judge's View.[39] There, Breyer argued that judges have six tools they can use to determine a legal provision's proper meaning: (1) its text; (2) its historical context; (3) precedent; (4) tradition; (5) its purpose; and (6) the consequences of potential interpretations.[40] Textualists, like Scalia, only feel comfortable using the first four of these tools; while pragmatists, like Breyer, believe that "purpose" and "consequences" are particularly important interpretative tools.[41]

Breyer cites several watershed moments in Supreme Court history to show why the consequences of a particular ruling should always be in a judge's mind. He notes that President Jackson ignored the Court's ruling in Worcester v. Georgia, which led to the Trail of Tears and severely weakened the Court's authority.[42] He also cites the Dred Scott decision, an important precursor to the American Civil War.[42] When the Court ignores the consequences of its decisions, Breyer argues, it can lead to devastating and destabilizing outcomes.[42]

In 2015, Breyer released a third book, The Court and the World: American Law and the New Global Realities, examining the interplay between U.S. and international law and how the realities of a globalized world need to be considered in U.S. cases.[43][44]

Other views

In an interview on Fox News Sunday on December 12, 2010, Breyer said that based on the values and the historical record, the Founding Fathers of the United States never intended guns to go unregulated and that history supports his and the other dissenters' views in District of Columbia v. Heller. He summarized:

We're acting as judges. If we're going to decide everything on the basis of history — by the way, what is the scope of the right to keep and bear arms? Machine guns? Torpedoes? Handguns? Are you a sportsman? Do you like to shoot pistols at targets? Well, get on the subway and go to Maryland. There is no problem, I don't think, for anyone who really wants to have a gun.[45]

In the wake of the controversy[46] over Justice Samuel Alito's reaction to President Barack Obama's criticism of the Court's Citizens United v. FEC ruling in his 2010 State of the Union Address, Breyer said he would continue to attend the address:

I think it's very, very, very important — very important — for us to show up at that State of the Union, because people today are more and more visual. What [people] see in front of them at the State of the Union is that federal government. And I would like them to see the judges too, because federal judges are also a part of that government.[47]

Honors

In 2007, Breyer was honored with the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award by the Boy Scouts of America.[48] In 2018, he was named to chair of the Pritzker Architecture Prize jury, succeeding previous chair Glenn Murcutt.[49]

See also

- Bill Clinton Supreme Court candidates

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Roberts Court

References

- Kersch, Ken (2006). "Justice Breyer's Mandarin Liberty". University of Chicago Law Review. 73: 759–822. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017.

As his decision to characterize both the New Deal and Warren Courts as centrally committed to democracy and 'active liberty' makes clear, Justice Breyer identifies his own constitutional agenda with that of these earlier courts, and positions himself, in significant respects, as a partisan of midcentury constitutional liberalism.

CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) - Urofsky, Melvin I. (May 25, 2006). Biographical Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court: The Lives and Legal Philosophies of the Justices. CQ Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781452267289.

- Genealogy records, Ancestry.com. Retrieved October 26, 2007

- Oyez Bio. Retrieved March 21, 2007

- Townley, Alvin (2007) [December 26, 2006]. Legacy of Honor: The Values and Influence of America's Eagle Scouts. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 56–59. ISBN 0-312-36653-1. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- Ray, Mark (2007). "What It Means to Be an Eagle Scout". Scouting. Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- Elinor Slater & Robert Slater (January 1996). Great Jewish Men. Jonathan David Publishers Inc. p. 73. ISBN 9780824603816.

- Oyez Bio. Retrieved March 21, 2007 (For Brown; need cite for Tribe)

- Toobin, Jeffrey (October 31, 2005). "Breyer's Big Idea". The New Yorker.

- Serial No. J-103-64 (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1995. p. 24. ISBN 01-6-046946-5.

- "Inaugural D.C. French Festival launches sans the Freedom Fries". Washington Life Magazine. October 12, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- The Justices of the Supreme Court. Retrieved April 6, 2012

- Thierer, Adam (December 21, 2010) Who'll Really Benefit from Net Neutrality Regulation?, CBS News

- The dilemmas of risk regulation – Breaking the Vicious Circle by Stephen Breyer, by Sheila Jasanoff. Issues in Science and Technology, Spring 1994.

- "Tulane Law School - Study Abroad". Law.tulane.edu. June 16, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- "Stephen Breyer: The Court and the World". WGBH Forum Network. November 6, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "Sharp Questions for Judge Breyer". The New York Times. July 10, 2004. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- Pedersen, Martin (August 8, 2018). "Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer: "To Understand a Building, Go There, Open your Eyes, and Look!"". Arch Daily. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- "Justice Breyer Should Recuse Himself from Ruling on Constitutionality of Federal Sentencing Guidelines, Duke Law Professor Says". Duke University News. September 28, 2004. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012.

- Berke, Richard (June 15, 1993). "The Overview; Clinton Names Ruth Ginsburg, Advocate for Women, to Court". The New York Times.

- Sunstein, Cass R. (May 2006). "Justice Breyer's Democratic Pragmatism" (PDF). The Yale Law Journal. 115 (7): 1719–1743. doi:10.2307/20455667. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Justice Breyer Favors 'Less Literal' Readings". newsmax.com. February 9, 2006. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- Wittes, Benjamin (September 25, 2005). "Memo to John Roberts: Stephen Breyer, a cautious, liberal Supreme Court justice, explains his view of the law". The Washington Post.

- Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000).

- Transcript of Discussion Between Antonin Scalia and Stephen Breyer Archived April 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. AU Washington College of Law, Jan. 13. Retrieved March 21, 2007

- Pearlstein, Deborah (April 5, 2005). "Who's Afraid of International Law". American Prospect Online. Archived from the original on April 7, 2005. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005); Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003); Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

- Gewirtz, Paul; Golder, Chad (July 6, 2005). "So Who Are the Activists?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 (2004).

- Sullivan, Kathleen M. (February 5, 2006). "Consent of the Governed". The New York Times.

- Lithwick, Dalia (December 6, 2006). "Justice Grover Versus Justice Oscar". Slate. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- "Interview with Nina Totenberg". NPR. September 30, 2005. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Sunstein at 12 ("Breyer thinks that as compared with a single-minded focus on literal text, his approach will tend to make the law more sensible, almost by definition. He also contends that it 'helps to implement the public's will and is therefore consistent with the Constitution's democratic purpose.' Breyer concludes that an emphasis on legislative purpose 'means that laws will work better for the people they are presently meant to affect. Law is tied to life; and a failure to understand how a statute is so tied can undermine the very human activity that the law seeks to benefit' (p. 100).")

- https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2004/10/florida-election-2000

- Feeney, Mark (October 3, 2005). "Author in the Court: Justice Stephen Breyer's New Book Reflects His Practical Approach to the Law". The Boston Globe.

- Berkowitz, Peter. "Democratizing the Constitution" (PDF). Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- Sunstein, pg. 7, citing Lori Ringhand, "Judicial Activism and the Rehnquist Court", available on ssrn.com and Cass R. Sunstein and Thomas Miles, "Do Judges Make Regulatory Policy? An Empirical investigation of Chevron", University of Chicago Law Review 823 (2006).

- Pakaluk, Maximilian (March 13, 2006). "Chambered in a 'Democratic Space'. Justice Breyer explains his Constitution". National Review. Archived from the original on March 18, 2006. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- (ISBN 978-0307269911); Fontana, David (October 3, 2005). "Stephen Breyer's "Making Democracy Work", reviewed by David Fontana". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- Stephen Breyer, Making Our Democracy Work: A Judge's View 74 (2010).

- Stephen Breyer, Antonin Scalia, Jan Crawford Greenburg (moderator) (December 5, 2006). A conversation on the constitution: perspectives from Active Liberty and A Matter of Interpretation (Video). Capital Hilton Ballroom - Washington, D.C.: The American Constitution Society; The Federalist Society.

- Jeff Shesol. Evolving Circumstances, Enduring Values, N.Y. Times, September 17, 2010.

- Witt, John Fabian (September 14, 2015). "Stephen Breyer's 'The Court and the World'". The New York Times.

- "The Court and the World: American Law and the New Global Realities". Penguin Random House. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- "Breyer: Founding Fathers Would Have Allowed Restrictions on Guns". Fox News. December 12, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Nagraj, Neil (January 28, 2010) "Justice Alito mouths 'not true' when Obama blasts Supreme Court ruling in State of the Union address", New York Daily News

- Blake, Aaron (December 12, 2010) "Justice Breyer: I'll go to State of the Union", The Washington Post

- "Distinguished Eagle Scout Award". Scouting (November – December 2007): 10. 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- "U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer Named Chair of Pritzker Architecture Prize Jury". Architect Magazine. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

Further reading

- Breyer, Stephen (2005). Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-307-27494-2.

- Stephen Breyer, The Federal Sentencing Guidelines and Key Compromises on Which They Rest, 17 Hofstra L. Rev. 1 (1988)

- Ronald Collins, "Hypothetically Speaking: Justice Breyer’s Dialectical Propensities" (Concurring Opinions Blog, February 28, 2014

External links

- Stephen Gerald Breyer at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Stephen Breyer at Ballotpedia

- Issue positions and quotes at OnTheIssues

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Review of Stephen Breyer's Active Liberty: Interpreting our Democratic Constitution

- 'Stephen Breyer, the court's necromancer', a book review of Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution in the New English Review

- "'Active Liberty' from Justice Stephen Breyer", October 20, 2005 NPR's Fresh Air

- "Supreme Court Justice Breyer on 'Active Liberty'" Part 1 of Interview, September 29, 2005 NPR's Morning Edition

- "Justice Breyer: The Case Against 'Originalists'" Part 2 of Interview, September 30, 2005 NPR's Morning Edition

- Justice Breyer's appearance on NPR's quiz show Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me, March 24, 2007

- WGBH Forum Network: one and a half hours with US Supreme Court Justice of Law Stephen Breyer, September 8, 2003. Description (archived) | Video.

- A film clip "The Open Mind - "Active Liberty" by Mr. Justice Breyer, Part I (2005)" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "The Open Mind - "Active Liberty" by Mr. Justice Breyer, Part II (2005)" is available at the Internet Archive

- Supreme Court Associate Justice Nomination Hearings on Stephen Gerald Breyer in July 1994 United States Government Publishing Office

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New seat | Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit 1980–1994 |

Succeeded by Sandra Lynch |

| Preceded by Levin H. Campbell |

Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit 1990–1994 |

Succeeded by Juan R. Torruella |

| Preceded by Harry Blackmun |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1994–present |

Incumbent |

| U.S. order of precedence (ceremonial) | ||

| Preceded by Ruth Bader Ginsburg as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |

Order of Precedence of the United States as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |

Succeeded by Samuel Alito as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |