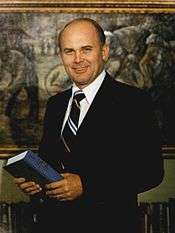

Dallin H. Oaks

Dallin Harris Oaks (born August 12, 1932) is an American jurist, educator, and religious leader who since 2018 has been the First Counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). He was called as a member of the church's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1984. Currently, he is the second most senior apostle by years of service[2] and is the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. However, consistent with long-established practice, due to Oaks serving in the First Presidency, M. Russell Ballard (third in seniority) currently serves as the quorum's acting president.

| Dallin H. Oaks | |

|---|---|

Oaks speaking at Harvard Law School in 2010 | |

| First Counselor in the First Presidency | |

| January 14, 2018 – present | |

| Called by | Russell M. Nelson |

| Predecessor | Henry B. Eyring |

| President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (with M. Russell Ballard as Acting President) | |

| January 14, 2018 – present | |

| Predecessor | Russell M. Nelson |

| LDS Church Apostle | |

| May 3, 1984 – present | |

| Called by | Spencer W. Kimball |

| Reason | Deaths of LeGrand Richards and Mark E. Petersen[upper-alpha 1] |

| Quorum of the Twelve Apostles | |

| May 3, 1984 – January 14, 2018 | |

| Called by | Spencer W. Kimball |

| End reason | Called as First Counselor in the First Presidency |

| 8th President of Brigham Young University | |

| In office | |

| August 1971 – August 1980[1] | |

| Predecessor | Ernest L. Wilkinson |

| Successor | Jeffrey R. Holland |

| Military career | |

| 1949–1954 | |

| Service/branch | United States National Guard |

| Unit | Utah National Guard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dallin Harris Oaks August 12, 1932 Provo, Utah, United States |

| Alma mater | Brigham Young University (B.S.) University of Chicago Law School (J.D.) |

| Occupation | Lawyer, Judge |

| Spouse(s) | June Dixon (1952–1998; deceased) Kristen Meredith McMain (2000–present) |

| Children | 6 |

| Parents | Lloyd E. Oaks Stella Harris |

| Awards | Canterbury Medal (2013) |

| Signature | |

Oaks was born and raised in Provo, Utah. He studied accounting at Brigham Young University (BYU), then went to law school at the University of Chicago, where he was editor-in-chief of the University of Chicago Law Review and graduated in 1957 with a J.D. cum laude. After law school, Oaks clerked for Chief Justice Earl Warren at the U.S. Supreme Court. After three years as an associate at the law firm Kirkland & Ellis, Oaks returned to the University of Chicago in 1961 as a professor of law. He taught at Chicago until 1971, when he was chosen to succeed Ernest L. Wilkinson as the president of BYU. Oaks was BYU's president from 1971 until 1980 and was then appointed to the Utah Supreme Court, on which he served until his selection to the LDS Church's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1984.

During his professional career, Oaks was twice considered by the U.S. president for nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court: first in 1975 by Gerald Ford, who ultimately nominated John Paul Stevens, and again in 1981 by Ronald Reagan, who ultimately nominated Sandra Day O'Connor.[3][4]

Background and education

Oaks was born in Provo, Utah on August 12, 1932 to Stella Harris and Lloyd E. Oaks. Through his mother, he is a 2nd great-grand-nephew of one of the three witnesses to the Book of Mormon, Martin Harris.[5][6] He was given the name Dallin in honor of Utah artist Cyrus Dallin. His mother was the artist's model for The Pioneer Mother, a public statue in Springville, Utah.[7] She was present for the unveiling of the statue less than three weeks before Dallin Oaks was born.[8] His father, who was an ophthalmologist, died of tuberculosis at the age of thirty-seven when Dallin was seven years old.[5][9]:32[10] After the death of her husband, Stella Oaks suffered an episode of mental illness and was unable to attend school and work for a time.[11] During this time, Oaks and his two younger siblings resided with their maternal grandparents in Payson, Utah. The loss of his father and the temporary loss of his mother caused him to have difficulties concentrating in school.[12] When he was about nine or ten years old, he resumed living with his mother, who had taken a position as a teacher in Vernal, Utah.[12]

Both of his parents were graduates of BYU. After his father died, his mother pursued a graduate degree at Columbia University and later served as head of adult education for the Provo School District. In 1956, she became the first woman to sit on the Provo City Council,[13] where she served for two terms.[14] In 1958, she also briefly served as Provo's assistant mayor.[15]

Oaks obtained his first job at the age of twelve at a radio repair shop sweeping the floors. Oaks graduated from Brigham Young High School in 1950. While in high school he played football[5][16] and became a certified radio engineer, working at radio stations in Vernal and Provo.[5] He then attended BYU, where he occasionally served as a radio announcer at high school basketball games. At one of these basketball games during his freshman year, he met June Dixon, a senior at the high school, whom he married during his junior year at BYU.[5] Due to his membership in the Utah National Guard and the threat of being called up to serve in the Korean War, Oaks was unable to serve as a missionary for the LDS Church.[9]:33[17] In 1952, Oaks married Dixon in the Salt Lake Temple. He graduated from BYU in accounting with high honors in 1954.[18][19]

Oaks subsequently attended the University of Chicago Law School on a three-year full tuition National Honor Scholarship, where he served as editor-in-chief of the University of Chicago Law Review during his senior year.[9]:33[20][21] Oaks graduated with a Juris Doctor cum laude in 1957.[18]

Career

After graduating from law school in 1957, Oaks spent a year as a law clerk to Chief Justice Earl Warren of the U.S. Supreme Court.[22] After his clerkship, he practiced at the law firm of Kirkland & Ellis in Chicago, specializing in corporate litigation.[9]:33[23] According to historian Lavina Fielding Anderson, Oaks was the first lawyer in his firm to represent an indigent before the Illinois Supreme Court.[24] Oaks left Kirkland & Ellis to become a professor at the University of Chicago Law School in 1961.[25] During part of his time on the faculty of the Law School, Oaks served as interim dean. He taught primarily in the fields of trust and estate law, as well as gift taxation law. He worked with George Bogert on a new edition of a casebook on trusts. In 1963, Oaks edited a book entitled The Wall Between Church and State covering discussions on views on the relationship of the government and religion in the law and the aptness of that metaphor. He also wrote on issues of evidence exclusion and the 4th amendment.[26] He was opposed to the exclusionary rule and favored prosection in "victim-less crimes".[9]:33[27] In the summer of 1964, he served as assistant state's attorney for Cook County, Illinois and as a visiting professor at the University of Michigan Law School during the summer of 1968.[28][29]

In 1968, he became a founding member of the editorial board of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought; he resigned from the journal in early 1970. In 1969, Oaks served as chairman of the University of Chicago disciplinary committee. In conducting hearings against the 160 students who had been involved in a sit-in at the administration building, Oaks was physically attacked twice. Over 100 students were eventually either suspended or expelled.[9]:33[30] During the first half of 1970, Oaks took a leave of absence from the University of Chicago while serving as legal counsel to the Bill of Rights Committee of the Illinois Constitutional Convention, which caused him to work closely with the committee chair, Elmer Gertz.[31] From 1970 to 1971, Oaks served as the executive director of the American Bar Foundation.[32] Oaks left the University of Chicago Law School when he was appointed the president of BYU in 1971. In 1975, Oaks was one of eleven considered to be nominated for the vacancy in the United States Supreme Court.[9]:33

Oaks also served five years as chairman of the board of directors of the Public Broadcasting Service[19] (1979–84)[33] and eight years as chairman of the board of directors of the Polynesian Cultural Center.[19] Additionally, over the course of his career, Oaks served as a director of the Union Pacific Corporation and Union Pacific Railroad.[34]

President of Brigham Young University

After the resignation of Ernest L. Wilkinson as BYU's 7th president, Neal A. Maxwell, who was the Commissioner of the Church Educational System, created a search committee for a new president, without any good leads on candidates. Both Wilkinson and University of Utah Vice President Jerry R. Anderson recommended to Maxwell that Oaks be interviewed.[35] He was offered the position and assumed his duties on August 1, 1971.[35]:10 From 1971 to 1980, Oaks served as BYU's 8th president.[19] Oaks oversaw the start of the J. Reuben Clark Law School and the Graduate Business School. Although university enrollment continued to grow and new buildings were added, neither was done at the pace of the previous administration under Wilkinson. Unlike his predecessor, Oaks took a hands-off approach to the discipline of the university students specifically in relation to the Church Educational System Honor Code. He believed that should be delegated to the dean of students.[9]:33 Oaks was well-liked and became a popular president, contrasting the austerity of the Wilkinson administration.[9]:34 Oaks created a Faculty Advisory Council where faculty members could be elected to the committee. He also instituted a three-tiered system of general education examinations for undergraduates.[9]:34

Other major changes under Oaks included implementing a three-semester plan with full fall and winter semesters, and a split spring and summer term. This also shifted the end of the fall term to before Christmas. Oaks also oversaw a large-scale celebration of the BYU centennial.[36] During his tenure at BYU, enrollment grew twenty percent; the average class size was maintained at thirty-four students. Library holdings increased to 2 million and the number of faculty members with doctorate degrees increased to 22 percent. The number of buildings constructed per year decreased to eight per year, compared to eleven per year during Wilkinson's administration.[9]:34 Church appropriations increased from $19.5 million to $76 million, making up approximately one-third of the university's income. Spending increased from $60 million to $240 million. Under the realization that faculty salaries were considerably low compared to other colleges in the western United States, BYU periodically increased the salary of employees, particularly female employees. Even with the raising of salaries, BYU faculty salaries were still about $1,000 less than other universities and colleges in the region.[9]:35 University income was bolstered by donations and fund-raising. In the mid-1960s, the university decided to name buildings after people who donated more than $500,000 to the university.[9]:36 The first building constructed entirely from private donations was the N. Eldon Tanner Building.[9]:36

During his administration, Oaks worked to focus on the equal treatment of women in the workplace. BYU instituted affirmative action policies to hire more women and worked to equalize salaries of men and women employees. Despite affirmative actions policies, the number of female full professors was almost unchanged after his presidency and BYU was behind other universities in the United States in the number of female employees by five percent.[9]:40 Oaks established an ad hoc committee over women's affairs to investigate gender discrimination at BYU. In 1975, BYU instituted policies prohibiting unfair distribution of church-sponsored scholarships based on gender.[9]:36–37 While at BYU, Oaks led an effort to fight the application of Title IX to non-educational programs at schools that did not accept direct government aid. BYU was one of two initial schools to voice opposition to these policies.[37] This issue ultimately ended in an agreement between the U.S. Department of Education and BYU that allowed BYU to retain requirements that all unmarried students live in gender-specific housing whether they lived on or off campus.[38] Oaks was a proponent for a lack of federal government intrusion in the private education sector and served as president of the American Association of Presidents of Independent Colleges and Universities for three years.[28][39]

During his presidency, he co-authored Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith with BYU professor of history Marvin S. Hill. The book received the Mormon History Association Best Book prize in 1976.[9]:33

During his presidency at BYU, Oaks was known for his moderate personal views which largely contrasted with the ultra-conservative views of his predecessor, Wilkinson. Oaks struggled during his presidency to distance BYU and the LDS Church from the partisan political atmosphere that had become typical under Wilkinson. Oaks established a policy to prevent BYU administrators from participating in partisan politics.[9]:219 Oaks continued to attempt to separate politics from BYU in his dealings with W. Cleon Skousen. Skousen, a known anti-communist, was hired as a BYU religion professor by Wilkinson. Other professors in the religion department were very critical of his hiring, believing he was unqualified for the position and was only hired because of his conservative viewpoints. During the Oaks administration, Skousen claimed to have been authorized to teach a new course about "Priesthood and Righteous Government", which would be published clandestinely under the name "Gospel Principles and Practices". This course was intended to be for ultra-conservative students to inform them of what to do about communist infiltration. Upon learning of Skousen's intentions, Oaks informed the First Presidency that he would not be permitted to teach that course.[9]:220 Skousen was told to stop mixing church doctrine and politics and to stop activities associated with his educational politics-based organization called the "Freeman Institute", now known as the National Center for Constitutional Studies. However, he largely ignored this instruction, and continued teaching his version of politically-infused doctrine until his retirement from BYU in 1978.[9]:220-21 By the mid-1970s, the relationship between Oaks and some of the more conservative members of the Board of Trustees became strained, particularly with Ezra Taft Benson. During Oaks's tenure, Benson condemned the undergraduate economics textbooks used as supporting "Keynesian" economics and he expressed concern as to whether faculty was teaching socialist economics.[9]:221 Oaks was displeased upon learning that the College of Social Sciences invited the leader of Utah's Communist party to speak to political science classes, believing that it could have set an undesired precedent. Not long afterward, Oaks became upset when he learned that Benson had invited activist Phyllis Schlafy to address students despite having been rejected by the Speakers Committee previously due to her "extreme" views.[9]:223 Most prominently, Oaks fought against the hiring of conservative Richard Vetterli despite the promise Wilkinson had made in hiring him before his resignation. Wilkinson lobbied Benson in appointing Vetterli after he left BYU and Benson and the Board of Trustees approved his appointment despite claims from Oaks that Vetterli was not qualified.[9]:224-25[40] Soon afterward, Oaks was released as BYU president and Jeffrey R. Holland took his place. The press cited the stand-off between Benson and Oaks in regards to Vetterli as a contributing factor to Oaks's release.[9]:225 Oaks on the other hand fully stated his leaving BYU was caused by his being worn out from having run the institution for nine years.

When Oaks had been in office for six years, he wrote to the First Presidency believing that he had become close-minded in his position and suggested that BYU establish a six or seven-year term limit for its presidents. His proposal was tabled for over two years before he was unexpectedly notified of his release by the news media. After serving for nine years, he stepped down in August 1980. Oaks was appointed to the Utah Supreme Court three months later.[9]:40

Utah Supreme Court

Upon leaving BYU, Oaks was appointed as a justice of the Utah Supreme Court on January 1, 1981, by Utah governor Scott M. Matheson.[12][28] He served in this capacity from 1980 to 1984, when he resigned after being appointed by the LDS Church as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[19] In 1975, Oaks was listed by U.S. attorney general Edward H. Levi among potential Gerald Ford Supreme Court candidates.[3] In 1981, he was closely considered by the Ronald Reagan administration as a Supreme Court nominee.[4][upper-alpha 2]

Scholarly research and notable opinions

As a law professor, Oaks focused his scholarly research on the writ of habeas corpus and the exclusionary rule. In California v. Minjares,[42] Justice William H. Rehnquist, in a dissenting opinion, wrote "[t]he most comprehensive study on the exclusionary rule is probably that done by Dallin Oaks for the American Bar Foundation in 1970.[43] According to this article, it is an open question whether the exclusionary rule deters the police from violating Fourth Amendment protections of individuals.[44]

Oaks also undertook a legal analysis of the Nauvoo City Council's actions against the Nauvoo Expositor. He opined that while the destruction of the Expositor's printing press was legally questionable, under the law of the time the newspaper certainly could have been declared libelous and therefore a public nuisance by the Nauvoo City Council. As a result, Oaks concludes that while under contemporaneous law it would have been legally permissible for city officials to destroy, or "abate", the actual printed newspapers, the destruction of the printing press itself was probably outside of the council's legal authority, and its owners could have sued for damages.[45]

As a Utah Supreme Court Justice from 1980 to 1984, Oaks authored opinions on a variety of topics. In In Re J. P.,[46] a proceeding was instituted on a petition of the Division of Family Services to terminate parental rights of child J.P.'s natural mother. Oaks wrote that a parent has a fundamental right protected by the Constitution to sustain their relationship with their child but that a parent can nevertheless be deprived of parental rights upon a showing of unfitness, abandonment, and substantial neglect.[47]

In KUTV, Inc. v. Conder,[48] media representatives sought review by appeal and by a writ of prohibition of an order barring the media from using the words "Sugarhouse rapist" or disseminating any information on past convictions of the defendant during the pendency of a criminal trial. Oaks, in the opinion delivered by the court, held that the order barring the media from using the words "Sugarhouse rapist" or disseminating any information on past convictions of defendant during the pendency of the criminal trial was invalid on the ground that it was not accompanied by the procedural formalities required for the issuance of such an order.[49]

In Wells v. Children's Aid Soc. of Utah,[50] an unwed minor father brought action through a guardian ad litem seeking custody of a newborn child that had been released to state adoption agency and subsequently to adoptive parents, after the father had failed to make timely filing of his acknowledgment of paternity as required by statute. Oaks, writing the opinion for the court, held that statute specifying the procedure for terminating parental rights of unwed fathers was constitutional under due process clause of United States Constitution.[51]

Among works edited by Oaks is a collection of essays entitled The Wall Between Church and State. Since becoming an apostle, Oaks has consistently spoken in favor of religious freedom and warned that it is under threat.[52] He testified as an official representative of the church on behalf of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act during congressional hearings in 1991,[53] and then again in 1998.[54] This was one of few occasions on which the church has sent a representative to testify on behalf of a bill before the U.S. Congress.[55][upper-alpha 3]

LDS Church service

In 1961, Oaks served as the stake mission president in the LDS Church's Chicago Illinois Stake. Then in 1963, he served as the second counselor in the presidency of the Chicago Illinois South Stake. He later served briefly as the first counselor in the same stake in 1970 but was released when he was appointed as BYU's president and moved to Utah.[28]

Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

On April 7, 1984, during the Saturday morning session of the LDS Church's general conference, Oaks was sustained an apostle and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve. In addition to advisory and operational duties, as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, Oaks is accepted by the church as a prophet, seer, and revelator.[18]

Although sustained on April 7, Oaks was not ordained an apostle until May 3, 1984.[18] He was given this time between sustaining and ordination to complete his judicial commitments.[56] Of the shift from judge to apostolic witness, Oaks commented, "Many years ago, Thomas Jefferson coined the metaphor, 'the wall between church and state.' I have heard the summons from the other side of the wall. I'm busy making the transition from one side of the wall to the other."[33] At age 51, he was the youngest apostle in the quorum at the time and the youngest man to be called to the quorum since Boyd K. Packer, who was called in 1970 at age 45.[57]

Oaks has spoken on behalf of the LDS Church on political issues, primarily those affecting religious liberty. In 1992, he testified before committees in the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives on the proposed Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), arguing that it would be a step in the right direction in maintaining protection of religious liberty after the precedent set by Employment Division v. Smith (1990).[18]:79-80 Oaks spoke again after the law had passed in 1993 and had subsequently been ruled unconstitutional a few years later.[18]:80

From 2002 to 2004, Oaks presided over the church's Philippines Area. Responsibility for presiding over such areas is generally delegated to members of the Quorums of the Seventy. The assignment of Oaks, along with Jeffrey R. Holland, who served in Chile at the same time, was aimed at addressing challenges in developing areas of the church, including rapid growth in membership, focus on retention of new converts, and training local leadership.[58]

On February 26, 2010, Oaks addressed students at the annual Mormonism 101 Series convened at Harvard Law School.[59][60]

In April 2015, included as part of an assignment to tour Argentina, Oaks gave a speech on religious freedom to the Argentine Council for International Relations.[61]

Among other assignments, Oaks has served as the senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles on the Church Board of Education and Boards of Trustees, including as chairman of its Executive Committee.

Counselor in the First Presidency

In January 2018, Russell M. Nelson became the church's new president. As the apostle second in seniority to Nelson, Oaks became President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. However, since Oaks was appointed as Nelson's First Counselor in the First Presidency, M. Russell Ballard was appointed as the quorum's acting president.[62] As First Counselor in the First Presidency, Oaks serves as First Vice Chairman of the Church Educational System's Board of Education and Board of Trustees.[63]

On June 1, 2018, Oaks gave the opening address at the First Presidency-sponsored "Be One" event, celebrating the 40th anniversary of the revelation extending the priesthood to all worthy males, regardless of race. Oaks spoke of seeing the hurt that the restriction had caused, more so while he was a resident of Washington, DC, and Chicago than he had seen in Utah. He also spoke of how the announcement had been a very emotional time for him. He noted that, prior to the 1978 announcement, having studied many explanations for the priesthood restriction, and having never been satisfied that any offered explanation for the restriction was inspired. Oaks called on people to not dwell too deeply on past policies but to look forward to a brighter future. He also denounced any prejudices, be they racial, ethnic, economic or others and called on anyone who suffered from such to repent.[64]

Awards and honors

Oaks earned the rank of Eagle Scout in 1947,[65] and he was honored with the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award in 1984.[65][66] He was named "Judge of the Year" by the Utah State Bar in 1984,[67] and he was bestowed the Lee Lieberman Otis Award for Distinguished Service by the Federalist Society in 2012.[23] He received the Canterbury Medal from the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty in 2013,[68] and he received the Pillar of the Valley Award by Utah Valley Chamber of Commerce in 2014.[69][70]

Students at the University of Chicago Law School created the Dallin H. Oaks Society to "increase awareness within the Law School community of the presence, beliefs, and concerns of law students who are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints".[71]

Family

Oaks married June Dixon on June 24, 1952. She died from cancer on July 21, 1998. They had six children, including Dallin D. Oaks, a linguistics professor at BYU,[72] and Jenny Oaks Baker, a violinist.[5] The Oaks' last child was born 13 years after their fifth child.[73]

On August 25, 2000, Oaks married Kristen Meredith McMain in the Salt Lake Temple.[74] McMain was in her early 50s and had previously served a mission for the LDS Church in the Japan Sendai Mission. McMain has bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Utah and a doctorate in curriculum and instruction from BYU.[75]

Works

- Articles

- Oaks, Dallin H. (February 1982), "Tribute to Lewis F. Powell, Jr.", Virginia Law Review, 68 (2): 161–167, JSTOR 1072876

- —— (August 1977), "BYU and Government Controls", Change, 9 (8): 5, JSTOR 40176982

- ——; Bentley, Joseph I. (1976), "Joseph Smith and Legal Process: In the Wake of the Steamboat Nauvoo", Brigham Young University Law Review, 1976 (3): 735–782

- —— (1976), "A Private University Looks at Government Regulation", Journal of College and University Law, 4 (1): 1–12, OCLC 425071127

- —— (Summer 1976), "Ethics, Morality and Professional Responsibility", Brigham Young University Studies, 16 (4): 507–516, OCLC 367531806, archived from the original on 2014-02-01

- —— (Summer 1970), "Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure", University of Chicago Law Review, 37 (4): 665–757, doi:10.2307/1598840, JSTOR 1598840, OCLC 486663762

- —— (January 1966), "Legal History in the High Court: Habeas Corpus", Michigan Law Review, 64 (3): 451–472, doi:10.2307/1287225, JSTOR 1287225, OCLC 485030899

- —— (Winter 1965), "The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor", Utah Law Review, 9 (4): 862–903, OCLC 83257504

- —— (Winter 1965), "Habeas Corpus in the States: 1776–1865", University of Chicago Law Review, 32 (2): 243–288, doi:10.2307/1598691, JSTOR 1598691, OCLC 486661030

- —— (1962), "The 'Original' Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Supreme Court", Supreme Court Review, 1962: 153–211, doi:10.1086/scr.1962.3108795, JSTOR 3108795, OCLC 479577199

- Books

- Oaks, Dallin H. (2014), Trust In His Promises - A Message for Women, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ISBN 978-1-60907-906-2

- —— (2011), Life's Lessons Learned: Personal Reflections, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ISBN 978-1-60908-931-3, OCLC 748290748

- —— (2002), With Full Purpose of Heart, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ISBN 978-1-57008-934-3, OCLC 50205573

- —— (1998), His Holy Name, Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, ISBN 978-1-57008-592-5, OCLC 40186303

- —— (1991), The Lord's Way, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ISBN 978-0-87579-578-2, OCLC 24467303

- —— (1988), Pure In Heart, Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, ISBN 978-0-88494-650-2, OCLC 51605024

- —— (1984), Trust Doctrines in Church Controversies, Salt Lake City: Mercer University Press, ISBN 978-0-86554-104-7, OCLC 10230752

- ——; Hill, Marvin S. (1975), Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith, Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-00554-1, OCLC 1528345

- ——; Lehman, Warren (1968), A Criminal Justice System and the Indigent: A Study of Chicago and Cook County, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, OCLC 227925

- Oaks, Dallin H.; Drinan, Robert F., eds. (1963). The Wall Between Church and State. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 232323.

- Oaks, Dallin H. (1957), The effects of Griffin v. Illinois on the States' administration of the criminal law, Chicago: Council of State Governments, hdl:2027/mdp.39015077934076, OCLC 5882888

- Chapters

- Oaks, Dallin H. (2001). "The Historicity of the Book of Mormon". In Hoskisson, Paul Y. (ed.). Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures. Religious Studies Center monograph series, v. 18. Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University. pp. 238–248. ISBN 978-1-57734-928-0. OCLC 48749213.

- —— (1999). "The missionary work of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". In Witte, John; Martin, Richard C. (eds.). Sharing The Book: religious perspectives on the rights and wrongs of proselytism. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. ISBN 1570752761. OCLC 42290427.

- —— (1995). "Rights and Responsibilities". In Etzioni, Amitai (ed.). Rights and the Common Good: the Communitarian Perspective. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312102720. OCLC 31614187.

See also

- Council on the Disposition of the Tithes

- Church Board of Education and Boards of Trustees

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

Notes

- Oaks and Russell M. Nelson were ordained to fill the vacancies in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles caused by the deaths of Richards and Petersen.

- The position was ultimately filled by Sandra Day O'Connor, fulfilling a campaign promise made by Reagan to appoint a woman to the court.[41]

- This was the third time that an official of the LDS Church brought an official stance to Congress, and in his testimony Oaks stated that his actions as an official church spokesperson were an exception to the general rule of the church not taking a stand on pending legislation.[55]

References

- Bergera, Gary James; Priddis, Ronald (1985). "Chapter 1: Growth & Development". Brigham Young University: A House of Faith. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 0-941214-34-6. OCLC 12963965.

- Apostolic seniority is generally understood to include all ordained apostles (including the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Seniority is determined by date of ordination, not by age or other factors. If two apostles are ordained on the same day, the older of the two is typically ordained first. See Succession to the presidency and Heath, Steven H. (Summer 1987). "Notes on Apostolic Succession" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 20 (2): 44–56..

- Yalof, David Alistair. Pursuit of Justices: Presidential Politics and the Selection of Supreme Court Justices (2001), p. 127.

- Gehrke, Robert (August 18, 2005), "LDS apostle was studied for '81 court", Salt Lake Tribune

- Flake, Lawrence K. (2001). Prophets and Apostles of the Last Dispensation. Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University. pp. 535–538. ISBN 1573457973.

- Oaks, Dallin H. "The Witness:Martin Harris - Dallin H. Oaks". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "The Pioneer Mother", history.utah.gov, Markers and Monuments Database, Utah State History, Utah Department of Heritage and Arts, archived from the original on 2012-07-08

- Hardy, Rodger L. (July 7, 2009), "Elder Oaks dedicates Springville sculpture garden", Deseret News

- Bergera, Gary James; Priddis, Ronald (1985). Brigham Young University: A House of Faith. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 0941214346.

- "Prophets and Apostles: Dallin H. Oaks", churchofjesuschrist.org, retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Prescott, Marianne Holman (February 2, 2018). "Get to Know President Dallin H. Oaks, Bold Leader". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. LDS Chuch News. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Walker, Joseph (January 17, 2018). "Read the 1984 bio of President Oak's life at the time of his call to be an apostle". Deseret News. Deseret News Publishing Company. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- "Harold E. Van Wagenen", Historical Provo, Provo City Library, archived from the original on 2014-02-27, retrieved 2014-01-17

- Wilkinson, Ernest L., ed. (1976), Brigham Young University: The First 100 Years, 4, Provo, Utah: BYU Press, pp. 10–13

- Historical Provol: George M. Hinckley, Provo City Library, archived from the original on 2014-02-27, retrieved 2014-01-17

- "Dallin H. Oaks as a young football player at Brigham Young High School", BYU Campus Photographs Collection, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, 1970–1975 [1946-1950], retrieved 2014-01-17

- Wilkinson. BYU. pp. 13–14.

- John R. Pottenger (2001), "Elder Dallin H. Oaks: The Mormons, Politics, and Family Values", in Formicola, Jo Renee; Morken, Hubert (eds.), Religious Leaders and Faith-Based Politics, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., pp. 71–87, ISBN 0847699625CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Dallin H. Oaks: Judge, University President, Apostle; Brigham Young High School Class of 1950", BYH Biographies: Alumni, Brigham Young High School Alumni Association, retrieved 2014-01-17

- "Dallin H. (Harris) Oaks", Grampa Bill's General Authority Pages, William O. Lewis, III, retrieved 2014-01-17

- Dunaway, Clint (5 January 2010), "Harvard Law School to Present Elder Dallin H. Oaks", MormonLawyers.com, Dunaway Law Group (Mesa, Arizona), archived from the original on 2013-10-21, retrieved 2014-01-17

- "Elder Dallin H. Oaks Selected Biographical Information". Mormon Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Federalist Society honors Elder Dallin H. Oaks, JD'57". May 15, 2012.

- Anderson, Lavina Fielding (April 1981). "Dallin H. Oaks". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Ensign. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Wilkinson. BYU. Vol. 4, p. 20.

- Bob Mims, "As Nelson’s longtime right-hand man, Oaks brings a keen legal mind to Mormonism’s new Big Three", Salt Lake Tribune, January 17, 2017

- Oaks, Dallin H. (1975). "Ethics, Morality, and Professional Responsibility". Brigham Young University Law Review. 1975 (3): 591–600. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Searle, Don L. (June 1984). "Elder Dallin H. Oaks". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Ensign. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Scott Taylor. "A Look At President Dallin H. Oaks" Deseret News January 16, 2018

- Wilkinson. BYU. Vol. 4, pp. 20–22.

- Wilkinson. BYU. Vol. 4, pp. 22–23.

- Taylor, "Oaks", Deseret News Jan 16, 2018

- Cazier, Bob (May 1984). "Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles". Ensign. pp. 89–90. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- Prescott, Marianne Holman (January 25, 2018). "Getting to know President Dallin H. Oaks of the First Presidency". Church News.

- Wilkinson, Ernest L.; Arrington, Leonard J.; Hafen, Bruce C., eds. (1976). Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press. ISBN 0842507086.

- Butterworth, Edwin, Jr. (October 1975), "Eight Presidents: A Century at BYU", Ensign

- "BYU Receives Support on Stand against Sex Bias Rules", Ensign, February 1978

- "BYU, Justice Department Agree on Housing Policy", Ensign, August 1978

- Raymond, Walter John (1992). Dictionary of Politics: Selected American and Foreign Political and Legal Terms. Brunswick Publishing Corp. p. 342. ISBN 155618008X.

dallin h oaks American Association of Presidents of Independent Colleges and Universities.

- Richards, Paul C. (Summer 1995). "Satan's Foot in the Door: Democrats at Brigham Young University" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 28 (2): 10. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "Ronald Reagan:Remarks Announcing the Intention to Nominate Sandra Day O'Connor to Be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States". The American Presidency Project. Gerhard Peters and John T Woolley. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- 443 U.S. 916 (1979).

- Rehnquist, William H. "California v. Minjares, 443 U.S. 916 (1979)". Justia. Justia. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Dallin H. Oaks, "Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure", 37 University of Chicago Law Review 665 (1970).

- Oaks, Dallin H. "The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor." Utah Law Review 9 (Winter 1965):862–903.

- 648 P.2d 1364 (Utah 1982).

- Oaks, Dallin Harris. "In Re JP, 648 P.2d 1364 (1982)". Justia. Justia. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- 668 P.2d 513 (Utah 1983).

- Oaks, Dallin Harris. "KUTV, INC. v. Conder, 668 P.2d 513 (Utah 1983)". Court Listener. Free Law Project. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- 681 P.2d 199 (Utah 1984).

- Oaks, Dallin Harris. "Wells v. Children's Aid of Soc. of Utah, 681 P.2d 199 (Utah 1984)". Court Listener. Free Law Project. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Landsberg, Mitchell (February 5, 2011), "Religious freedom under siege, Mormon leader says", Los Angeles Times

- Gedicks, Frederick M. (1999), "No Man's Land: The Place of Latter-day Saints in the Culture War", BYU Studies, 38 (3): 148, archived from the original on 2014-02-01

- Oaks, Dallin H. (Spring 1998), "Statement Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary" (PDF), Clark Memorandum, J. Reuben Clark Law School, BYU: 21

- "Elder Oaks Testifies before U.S. Congressional Subcommittee", Ensign, News of the Church, July 1992

- Hinckley, Gordon B. (May 1984), "Sustaining of Church Officers", Ensign: 4.

- Springer, Carly M. "5 Fun Facts about President Oaks". LDS Living. Deseret Book Company. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Moore, Carrie (April 10, 2002). "2 apostles assigned to live outside U.S". Deseret News.

- "Apostle Addresses Harvard Audience on Mormon Faith". Newsroom [MormonNewsroom.org]. News Story. LDS Church. 26 February 2010. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- Sheffield, Carrie; Askar, Jamshid (February 27, 2010), "Don't marginalize religion, Elder Oaks says to Harvard law students", Deseret News, retrieved 2014-01-14

- Jason Swensen, "Elder Oaks warns of rising secularism, champions religious freedom" Archived 2018-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, Church News, April 23, 2015.

- "President Dallin H. Oaks". General Authorities and General Officers. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Church Educational System Administration". Church Educational System. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Walch. "President Oaks acknowledges pain of past LDS restriction on priesthood, temple blessings for blacks", in Deseret News, June 1, 2018

- "Distinguished Eagle Scouts". Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "National Eagle Scout Association". Archived from the original on 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- "Elder Dallin H. Oaks Honored for Championing Religious Freedom", Newsroom [MormonNewsroom.org], News Release, LDS Church, May 16, 2013

- "Lighter side of Elder Oaks shines at Pillar of the Valley". Utahvalley360.com. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "President Dallin H Oaks". Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- "Dallin H. Oaks Society", law.uchicago.edu, Student Organizations, University of Chicago Law School, retrieved 2014-01-17

- "Dallin Dixon Oaks", Department of Linguistics and English Language, Directory, BYU, archived from the original on 2011-05-16

- Walker "Oaks", Deseret News, April 1984

- Oaks, Dallin H. (October 2003), "Timing", Ensign

- "2011 Time Out for Women Tour: Kristen M. Oaks", deseretbook.com, Deseret Book, archived from the original on 2012-03-06

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dallin H. Oaks. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dallin H. Oaks |

- Dallin H. Oaks, official church biography.

- Dallin H. Oaks, Mormon Newsroom Leader Biographies.

- Dallin H. Oaks, short biography.

- Dallin H. Oaks, Dallin H. Oaks, BYU President

- Dallin H. Oaks, Grampa Bill's G.A. (General Authority) Pages.

- Works by or about Dallin H. Oaks in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Russell M. Nelson |

Quorum of the Twelve Apostles May 3, 1984 – January 14, 2018 |

Succeeded by M. Russell Ballard |

| President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles January 14, 2018 – With: M. Russell Ballard (Acting) |

Succeeded by Incumbent | |

| Preceded by Henry B. Eyring |

First Counselor in the First Presidency January 14, 2018 – | |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Ernest L. Wilkinson |

President of Brigham Young University 1971 – 1980 |

Succeeded by Jeffrey R. Holland |