Coat of arms and flag of Transylvania

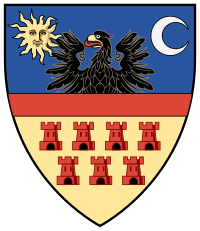

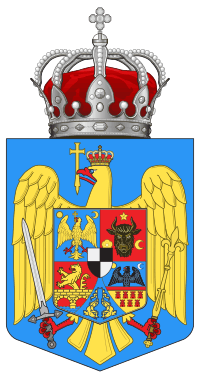

The coat of arms and flag of Transylvania were granted by Maria Theresa in 1765, when she established a Grand Principality within the Habsburg Monarchy. While neither symbol has official status in present-day Romania, the coat of arms is marshalled within the national Romanian arms; it was also for decades a component of the Hungarian arms. In its upper half, it prominently includes the eagle, which may have been one of the oldest regional symbols, or is otherwise a localized version of the Polish eagle.

| Coat of arms of Transylvania | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armiger | Grand Principality of Transylvania |

| Adopted | November 2, 1765 |

| Blazon | Per fess Azure and Or, a fess Gules between in chief an eagle issuant from the division Sable flanked by a sun-in-splendour Or and an increscent Argent, and in base seven towers Gules. |

| Earlier version(s) | Transylvanian Principality (after ca. 1580) |

| Use | No current official status |

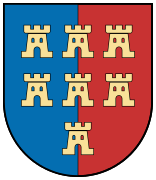

An early version of the Transylvanian charges was first designed in Habsburg Hungary at some point before 1550, and only attested as in use by the Transylvanian Principality in or after 1580. The first Prince to recognize and use them was Sigismund Báthory. They entered the heraldic patrimony and, during Ákos Barcsay's reign, were codified as representing three separate jurisdictions: the eagle stood for Transylvania-proper, the sun-and-crescent is for Székely Land, while the seven towers are canting arms of the Saxon-populated cities. They are also widely understood as ethnic symbols of the three privileged nations (excluding Romanians), but this interpretation is criticized as inaccurate by various historians.

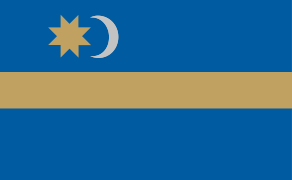

Before Maria Theresa, Transylvania's rulers used a variety of flags, which more often than not included family or factional symbols, such as the Báthory "wolf teeth". Transylvania's Habsburg flag and the flag of Romania are tricolors which resemble each other superficially: Transylvania has blue-red-yellow displayed horizontally, while Romania has blue-yellow-red, vertically. The Transylvanian colors were codified from the heraldic tinctures, but various Romanian scholars ascribe them a Dacian origin and links to the Romanian ethnogenesis. On such grounds, the Transylvanian colors were often used in Austria-Hungary to camouflage celebrations of Romanian nationalism. Saxon organizations have traditionally reduced the tricolor to a blue-over-red arrangement, while Székely Land autonomists use a blue-gold-silver pattern.

History

Origins

The region had a distinct jurisdiction under a Voivode of Transylvania from the 12th century. Whether it used a heraldic symbol at this stage is a matter of dispute among modern heraldists. Dan Cernovodeanu dismisses the notion, arguing that there was a general disinterest in regional heraldry, manifested throughout high-medieval Hungary.[1] The Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms claims a "green flag with a red scimitar" as standing for the "Kingdom of Siluana" or "Septem Castra".[2] The latter is a reference to Transylvania as the country of "seven cities". According to historian Iulian Marțian, this name may predate Hungarian conquest, and is traceable to Roman Dacia. He argues that seven towers may have already been a Transylvanian symbol at that stage, noting that the "Dacian" metropolis of Sirmium was represented by a tower on a field of gules.[3]

Hungarian sources, analyzed in the 19th century by Josef Bedeus von Scharberg[4] and Nicolae Densușianu,[5] suggest that Transylvanian troops fought under an eagle banner; the accuracy of such reporting is altogether doubtful.[6] Several 15th-century armorials also feature a "Duke of Weydn" or "Weiden", which may refer to the Transylvanian Voivodes or Dukes, using an eagle on a field of argent and azure.[7] Among the modern experts, Tudor-Radu Tiron argues for the existence of a Transylvanian eagle shield, taking as evidence a Black Church relief and the attested seal of Fehér County. Both, he argues, may be "heraldizations" of the Roman aquila, and as such folk symbols of "Dacia".[8]

At this earliest stage, individual Voivodes also had their own attested arms. Thomas Szécsényi, who governed in the 1350s, used a lion combined with the Árpád stripes.[9] One theory proposes that Bartholomew Drágffy, rising to the position in the 1490s, used the aurochs head, which was also a staple of Moldavian heraldry.[10] The right to use individual coat of arms was severely limited by the codes of István Werbőczy, introduced in 1514. These effectively excluded many Vlachs (Romanians) from the ranks of Hungarian nobility.[11]

Some alternative heraldic symbols were introduced by two distinct ethnic communities: the Transylvanian Saxons (German-speaking) and the Székely (Hungarian-speaking). The former group had its "one single seal" as early as 1224, though it is not recorded what that symbol was. According to Marțian, its design was the same as a 1302 seal, which depicts three kneeling men and a standing one holding up a crown. It was replaced in 1370 by a variant combining the Hungarian and Capetian arms of Louis I, alongside an eagle-and-rose composition.[12] The original Székely symbol featured an arm holding a sword, often piercing through a crown, a bear's severed head, and a heart, sometimes alongside a star-and-crescent; the field, though often interpreted as azure, was most likely gules.[13] Threatened by the peasant revolt of 1437, the estates of the realm established a regime of feudal privileges known as Unio Trium Nationum. This event is traditionally held as the source of a new Székely coat of arms, which only shows the sun and waxing moon (see Count of the Székelys).[14] Marțian notes that these two devices were also used in medieval armorials as visual representations of Cumania and of the Vlachs.[15]

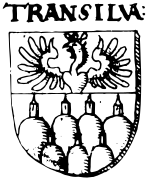

The Ottoman Empire eventually took hold of central Hungary in 1541, leaving Transylvania to reestablish itself as a rump Hungarian Kingdom. During the first decades of reorganization under John Sigismund Zápolya, the region effectively used Hungary's arms,[16] although one popular legend attributes the creation of Transylvania's arms to the same Zápolya.[17] Zápolya's military ordinances imposed recruitment rules on the counties of Transylvania, specifying that each county would have its own banner.[18] Meanwhile, a rival claim to Transylvania had been placed by Habsburg Hungary, which was part of the larger Habsburg Monarchy and thus dynastically attached to the Holy Roman Empire. A Transylvanian symbol was probably designed at the court of Ferdinand I, and was based on Saxon heraldry, showing crossed swords and a triquetra. This is the version published by Georg Reicherstorffer (1550) and Martin Schrot (1581).[19]

A manuscript at the Bavarian State Library (Cod. icon. 391) preserves what is perhaps the first version of the modern Transylvanian arms—designed under Habsburg influence, and probably dating back to Zápolya's reign.[20] It has a crowned eagle's head in chief, and seven towers, gules, on seven hills, vert, over a argent field. Its design may join the earlier eagle flag with canting arms for Siebenbürgen ("Seven Cities", the German name of Transylvania); the color scheme seems to be purposefully based on the Hungarian arms.[21] In the 1560s, the seven towers were featured on coinage issued by Habsburg client Iacob Heraclid, who became Prince of Moldavia. These artifacts also feature the Moldavian aurochs and the Wallachian bird, showing Heraclid's ambition of unifying the three realms under one crown.[22] In 1596, Levinus Hulsius of Nuremberg published another recognizable version of Transylvania's arms, showing a crowned eagle over seven hills, with each hill topped by a tower; tinctures cannot be reconstructed.[23]

.svg.png) Attributed flag of the "Kingdom of Siluana" in the Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms

Attributed flag of the "Kingdom of Siluana" in the Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms.svg.png) "Duke of Weiden" arms, possibly representing the Voivode of Transylvania (1438 version)

"Duke of Weiden" arms, possibly representing the Voivode of Transylvania (1438 version)%2C_hypothetical_colors.svg.png) Saxon arms of Hermannstadt (before 1470); colors are hypothetical

Saxon arms of Hermannstadt (before 1470); colors are hypothetical Banner of the Székelys, ca. 1500

Banner of the Székelys, ca. 1500 Seal of Transylvania with swords and triquetra (Georg Reicherstorffer variant, 1550)

Seal of Transylvania with swords and triquetra (Georg Reicherstorffer variant, 1550)

Báthorys and Michael the Brave

The Eastern Kingdom was downgraded by its Ottoman suzerains to a Transylvanian Principality in 1570. Like with other Ottoman clients, the new Princes were granted banners-of-rule by the Sublime Porte; these were paraded in ceremonies, alongside the kaftans and scepters.[24] Transylvania also preserved the Zápolyan practice of organizing military units under separate county banners.[25] In heraldic practice, it perpetuated the use of Hungarian royal diadems. Their mantling was gules–argent and or–azure, which were probably remnants of the Croatian and Dalmatian tinctures.[26]

Zápolya's former realm was taken over by Stephen Báthory in 1576. Though he was the first to emphasize his princely title, he did not create any heraldic symbol for the region, and instead introduced the Báthory family arms (three "wolf's teeth") as a stand-in.[27] Serving as regent in 1580, Christopher Báthory may have issued a heraldic medal showing an eagle and seven towers alongside the Székely sun and waxing moon, but this may be a forgery.[28] Stephen's son, Sigismund Báthory, rejected Ottoman rule and joined the Habsburgs in the Holy League, being recognized as a Reichsfürst in 1595. This allowed him to marshall the Báthory and Hulsius versions into a single coat of arms, which also included the Moldavian aurochs and the Wallachian eagle, reflecting Báthory's claim to suzerainty over both countries.[29]

No colored versions of the seal survive. While tinctures have been deduced by the authors of Siebmachers Wappenbuch during the 1890s,[30] and are described by historian Constantin Moisil as sable devices on azure (for the eagle) and or (for the seven towers),[31] such readings are criticized by Cernovodeanu—as he notes, the seal's hatching preceded modern conventions, and therefore could not be properly reconstructed.[32] A relief of the Transylvanian arms was carved, probably on Sigismund's orders, in the Moldavian capital of Suceava, again highlighting his regional dominance. This variant kept only the seven towers, and replaced the eagle with an "imperial crown" supported by two lions.[33] Sigismund's heraldry standardizes the towers' depiction by removing the corresponding hills. It, therefore, became the basic template for more modern subsequent representations, being also the first one to definitely include the Székely sun-and-moon.[34]

The latter innovation is often described as fulfilling the visual representation of the Unio Trium Nationum, with the implicit marginalization of Transylvania's Romanians.[35] In this reading, the eagle represents Hungarian nobility and the towers are a stand-in for the Saxon cities. According to historian Szabolcs de Vajay, neither of these symbols preexisted the 1590s but were appropriated by their armigers after first appearing on Sigismund's seal.[36] Similarly, Marțian argues that the Saxons circulated an invented tradition about the origins of the seven towers as an ethnic symbol, backdating them to the 13th century.[37] Joseph Bedeus von Scharberg and other researchers propose that the eagle is from the coat of arms of Poland, hinting to Stephen Báthory's rule as King of Poland.[38] The bird had special significance for the superstitious Sigismund, who credited his victories in Wallachia to ornithomancy; in similar vein, he used an alternative coat of arms depicting three suns, which apparently referred to his witnessing a sun dog.[39]

In 1599, following defeat at Șelimbăr, the Báthorys were ousted from Transylvania by Wallachian Prince Michael the Brave, who later also extended his control into Moldavia. During his interval in power, Michael issued documents bearing new seals, which included both Wallachian and Moldavian symbols; also featured were two lions rampant. Romanian scholars are in disagreement as to whether the latter symbol is meant to represent Transylvania. While Grigore Tocilescu, Dimitrie Onciul and Paul Gore have supported the notion, others, including Moisil and Ioan C. Filitti, have cast "serious doubts", and see the lions as Michael's personal emblem.[40] Cernovodeanu proposes that the lions could represent Transylvania indirectly, as "Dacia", noting similar descriptions of "Dacian arms" in the works of Nicolae Costin and Pavao Ritter Vitezović.[41]

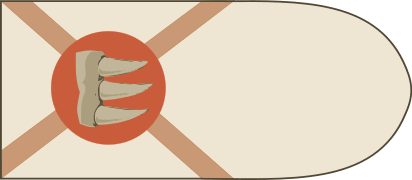

Flags captured by Michael and his Habsburg ally Giorgio Basta during the Battle of Guruslău, some of which are also depicted in paintings by Hans von Aachen, give additional insight into the Principality's heraldic symbolism. Samples include blue and white Székely flags displaying the old and new symbols together.[42] A variety of Báthory flags were captured on the field of battle, prominently displaying the "wolf's teeth", but with no element from the coat of arms.[43] As noted in 1910 by historian Iosif Sterca-Șuluțiu, "they are of all sort of colors and shapes, none of which have any significance."[44]

Levinus Hulsius version of 1596

Levinus Hulsius version of 1596 Sigismund Báthory's composite arms

Sigismund Báthory's composite arms Seal used by Michael the Brave, featuring the two lions

Seal used by Michael the Brave, featuring the two lions "Wolf's teeth" banner, captured in the Battle of Guruslău

"Wolf's teeth" banner, captured in the Battle of Guruslău.svg.png) "Wolf's teeth" badge from a 1645 map

"Wolf's teeth" badge from a 1645 map

17th-century variants

One of Michael's allies and rivals, Moses Székely, briefly took the throne of Transylvania in 1603. His seals included a representation of the lions rampant, but there is disagreement as to whether these alluded to Michael's heraldry or to Moses' own family arms.[45] Taking over as Prince in 1605, Stephen Bocskai removed the lions and briefly restored the seven mountains, also changing the overall arrangement.[46] Bocskai was also the first Transylvanian Prince to include the state arms on coinage, featuring them alongside his family arms or those of the Zápolyan monarchy.[47] His successor Sigismund Rákóczi used a different design for the eagle which, according to historians such as Bedeus and Marțian, was actually a revival of the Polish arms;[48] Moisil sees it as a borrowing from the Prince's personal arms.[49] At that stage, a Transylvanian eagle was used on coinage issued by the Saxon city of Kronstadt (Brașov), which had risen in rebellion against Rákóczi.[50]

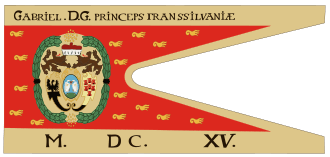

Before 1621, anti-Habsburg Prince Gabriel Bethlen incorporated his claim to the Lands of the Hungarian Crown by depicting Hungary and Transylvania's arms on a single shield.[51] His crimson swallowtail, reuniting the Bethlen family arms and Transylvanian symbols (black eagle, seven red towers on gold etc.), was preserved and reproduced in later centuries.[52] Historian Vencel Bíró argues that in the 1630s, under George I Rákóczi, Transylvania already used a "blue, red, gold-yellow" tricolor as its state flag. This appears in heraldry used by the Transylvanian post riders.[53]

George II Rákóczi used a vast range of Transylvanian arms, freely mixing the elements and including his family's arms.[54] A portrait of his by John Overton features the three elements as separate shields, with the Székely moon wrongly depicted as a bird's head.[55] From 1637, the regular coat of arms, combined with dynastic symbols, was still used as a watermark by the Rákóczian paper mill of Lámkerék (Lancrăm).[56] Between the reigns of Bethlen and Rákóczi, knowledge about "heraldic art" was spread in Transylvania by writer Ferenc Pápai Páriz, whose book standardized descriptions of both princely families' arms.[57] While this revival saw a surge in the number of arms granted by Transylvanian Princes to their Transylvanian or Moldavian subjects and allies, the arms themselves were seldom depicted, as most recipients could not afford the cost of having them painted.[58]

Various other designs of the state arms, featuring the same basic elements, continued under several Princes until 1659, when Ákos Barcsay restored Sigismund's basic arrangement. This was probably the result of a ruling by the Transylvanian Diet, associating each heraldic element with a distinct entity of Transylvania, and issuing orders for each to be made into a separate seal.[59] A Diet writ also specified the introduction of distinct arms for Partium—an area of Hungary-proper which had been attached to the Principality. This subregion was to be represented by four bars and a Patriarchal cross.[60] Nevertheless, a symbol of Partium never appeared on Barcsay's Transylvanian arms, and the notion was eventually abandoned.[61] As attested in the 1650s by Claes Rålamb, the various towns of this area flew their own symbols, a multitude of "flags and colors".[62]

The 1659 ruling is widely read as the first to explicitly associate each component privileged class, social as well as national.[63] This interpretation is seen as erroneous by various historians: Marțian notes that the bird was not intended as a stand-in for the Hungarian Transylvanians, but for the multinational nobility and the regular, non-autonomous, counties;[64] this verdict is also backed by Attila István Szekeres and Sándor Pál-Antal: the Diet ascribed a primarily geographical meaning to each element, separating between "the counties", represented by the eagle, and the two autonomous enclaves.[65] Moisil also highlights a non-ethnic definition of the "nation" represented by the eagle, but also comments that, by that moment in time, Romanian nobles were being "gradually Magyarized".[66]

Habsburg conquest

According to Moisil, the late adoption of a Transylvanian coat of arms, and its "few connections with the past and soul of the Romanian people", meant that the symbolism was rarely evoked in Romanian folk literature—unlike the Moldavian or Wallachian arms.[67] The tower symbolism preserved some popularity in Romanian-inhabited areas outside Transylvania's borders. Shortly before Barcsay's ascendancy, Wallachian intellectual Udriște Năsturel used a heraldic device with gules tower appearing in crest. Researchers see this usage as reflecting a belief that "red towers" stood for Transylvanian cities in general, and for Udriște's claim to descent from the Boyar of Fogaras.[68] Seven towers of presumed Transylvanian origin were also depicted on a stove top, dated to ca. 1700, which was recovered during excavations at the Moldavian court in Huși.[69]

In the 1680s, at the height of the Great Turkish War, Emeric Thököly led a Hungarian–Transylvanian Kuruc army which assisted the Ottomans against the Habsburgs. This force is known to have used two banners: a blue one with an arm-and-sword, and a red one with the Thököly arms.[70] The revolt failed; Transylvania and Partium were fully incorporated into the Habsburg realms under the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699). In anticipation, Leopold I already used the Transylvanian arms on his coinage by 1694.[71] Habsburg Transylvania, which remained a principality attached to the Hungarian Crown, issued polturas with its own markings throughout the early 18th century.[72] These depictions introduced the practice of showing regional arms superimposed on the Reichsadler, something which was also done, with the respective arms, for coins used in Hungary, Milan or Tuscany.[73] In Partium, Leopold also granted nobility to the Romanian peasant families Sida and Iuga in 1701. Their diploma has separate shields of Transylvania, showing the towers on azure and the eagle sable on a barry shield of or and gules. The Partium arms with the Patriarchal cross are also revived for this document, with bars of or and gules.[74]

Transylvanian independence was briefly restored in the War of 1703–1711 by Prince Francis II Rákóczi, who also claimed the Hungarian throne. His cavalry fought under a seven-bars variant of the Árpád stripes, with the slogan IUSTAM CAUSAM DEUS NON DERELINQUET ("God will not abandon the just cause").[75] Tradition about Transylvania's coat of arms was preserved in other Hungarian circles: in 1734, Ioannes Szegedi published an engraving of it, showing a crowned eagle, sable, and seven towers, argent, over seven mountains, vert, all on azure background; here, the Székelys were no longer represented by celestial bodies, but by the older arm-and-sword.[76]

The Dictionarium heraldicum, printed at Vienna in 1746, referred to the Transylvanian arms as being: "Seven cities over which shines the moon".[77] Regional symbolism was again in focus during the 1740s, when Maria Theresa took over as Queen and Empress. A medal she issued in 1740 is also the first official one to have readable hatching, with an azure background throughout.[78] The following year, Hristofor Žefarović published a version more closely resembling the Báthory design but replacing the "teeth" with an Austrian badge. Žefarović placed the eagle on a field of or; his towers and mountains were argent and placed on a gules field.[79]

Arms used by Princess-consort Sophia Báthory (1681)

Arms used by Princess-consort Sophia Báthory (1681) Partium arms, as used in 1701

Partium arms, as used in 1701 Francis II Rákóczi's version of the Árpád stripes

Francis II Rákóczi's version of the Árpád stripes Transylvanian arms in Ioannes Szegedi's version (1734)

Transylvanian arms in Ioannes Szegedi's version (1734) Hristofor Žefarović's version (1741)

Hristofor Žefarović's version (1741)

Standardized symbols

Upon creating a "Grand Principality of Transylvania" on November 2, 1765, Maria Theresa finally standardized the coat of arms, introducing the definitive tinctures and adding the gules fess.[80] Following this redesign, the crescent was also rendered as a waning moon.[81] These new Transylvanian arms were also the basis for a Transylvanian blue-red-yellow banner, which may also date back to 1765.[44][82] Transylvania's promotion and its modernized heraldry were both supervised by Chancellor Wenzel von Kaunitz, who encouraged a rift between Transylvania and the Hungarian Kingdom; on such grounds, Kaunitz rejected heraldic submissions by the Hungarian nobles, who wished to include a Patriarchal cross into the design.[83] In 1769, he shocked his Hungarian adversaries by refusing to add the Transylvanian arms into those of the Kingdom.[84]

In approving of this exclusion, Maria Theresa noted that interfering with the arms would upset Transylvania's population.[85] By then, Romanians were readily associating with imperial symbolism. Already in 1756, Petru Pavel Aron sponsored an all-Romanian Hussar unit, which flew its own flag in the Seven Years' War.[86] Historians Lizica Papoiu and Dan Căpățînă propose that the definitive selection of azure for the field displaying the eagle was meant to represent Maria Theresa's Romanian subjects, being derived from the Wallachian arms (which, by then, were also standardized as azure). As they note, those Romanian serfs who were raised into Transylvania's nobility also opted for azure shields.[87] In 1762, Adolf Nikolaus von Buccow was entrusted with conscripting Székely and Romanian (or "Dacian") men into the Military Frontier, under a shared Transylvanian coat of arms.[88]

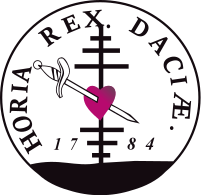

Romanian loyalism remained high as the Székely rebelled (see Siculicidium). A blason included in the 1784 Molitvenic ("Prayer Book") of the Romanian Eastern Catholics focuses attention on the Reichsadler rather than the Transylvanian eagle, expressing solidarity with the "well-beloved", reform-minded, Joseph II.[89] Late that year, during the anti-Hungarian revolt of Romanian peasants, insurgents reportedly carried a flag with Joseph's portrait.[90] Their leader Horea reportedly used an emblem showing a triple cross, either alongside a dagger-pierced heart, or with seven mounds that may evoke the seven cities on the official arms; this arrangement sometimes included a slogan, NOS PRO CESARE, attesting Horea's Habsburg loyalties.[91] In 1791, Romanian intellectuals of the "Transylvanian School" addressed Leopold II an essay demanding increased social rights. Titled Supplex Libellus Valachorum, it was illustrated with an allegory which included the Transylvanian arms.[92]

Following the consolidation of a Habsburg-ruled Austrian Empire in 1804, Transylvania became one of the crownlands depicted on the Reichsadler wings; the first such depiction was in 1806.[93] The local flag was still used in tandem with a multitude of other banners. As reported by historian Auguste de Gérando, in the 1840s Transylvania's chartered towns (oppida nobilia) formed individual units of the Landwehr under their respective county banners.[94] Coins minted in Transylvania no longer had distinguishing heraldic markings after 1780,[95] though Reichsadler-with-arms designs continued to be used by other institutions into the 19th century, including by the salt monopoly in Vizakna (Ocna Sibiului).[96] While the tricolor scheme became a standard in official Habsburg heraldry, nostalgic or ill-informed heraldists continued to use variants without the bar, as with the 1784 Molitvenic.[97] Mapmaker Johann Joseph von Reilly also preferred a three-shield version: the eagle and the Székely sun-and-moon each on gules, and the seven mountains on argent.[98]

In de Gérando's time, the coat of arms was interpreted as an actual visual record of ethnic divisions, omitting the "most populous inhabitants", who were the Romanians, as well as the "tolerated nation" of Armenians.[99] Transylvanian regional symbols, and in particular the chief portion of the crest, were now reclaimed by members of the Hungarian community; the eagle was interpreted a version of the mythical Turul.[100] "The sun, the moon and the eagle" under a "Hungarian sky" were thus referenced in a song by Zsigmond Szentkirályi, dedicated to Governor György Bánffy. It was performed in 1821 at the National Magyar Theater, on a stage bearing a large version of the Transylvanian arms.[101] By contrast, a variant with only towers and two eagles in supporters was used on an 1825 lithograph depicting the Saxon city of Kronstadt.[102]

Reichsadler variant in the 1784 Molitvenic

Reichsadler variant in the 1784 Molitvenic One of Horea's reported emblems

One of Horea's reported emblems Transylvanian arms as used by Chancellor Sámuel Teleki

Transylvanian arms as used by Chancellor Sámuel Teleki.svg.png) Arms of Francis as the first Emperor of Austria

Arms of Francis as the first Emperor of Austria Székely seal in 1832

Székely seal in 1832

Revolutionary usage

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 proclaimed Transylvania's absorption by the Hungarian Kingdom, moving toward separation from the Habsburg realm. Revolutionary leader Lajos Kossuth approved a new set of national symbols, including a "medium" coat of arms with marshalled Transylvanian symbols. Unusually, this depiction used the pre-standardization variant of 1740.[103] Hungarian communities were committed to the new red-white-green tricolor, whereas the Saxons adopted a variant of the German colors with the arms of Transylvania displayed. The issue caused a standoff between the two camps at Regen (Reghin).[104]

The advent of Romanian nationalism produced immediate grievances against this regime and its official heraldry; throughout the Revolution, Romanians and Hungarians fought each other for control of Transylvania, with the former largely loyal to the Habsburg crown. Romanian intellectuals looked forward to a new arrangement in Transylvania, also proposing a new class of symbols. Their design prominently included a female allegory of "Dacia Felix", alluding to the origin of the Romanians, as well as a lion and aquila.[105] Another proposal was consciously based on 3rd-century coinage issued by Philip the Arab. Also keeping the 1765 format, it added vexilla with markings for Legio V Macedonica and Legio XIII Gemina.[106]

Transylvania's Romanian nationalists rallied under their own flags, which were generally horizontal variants of the pan-Romanian tricolor, blue-yellow-red, notably used at the May 1848 assembly in Blaj (Balázsfalva).[107] Romanian flags appeared there alongside the Habsburg colors, showing that Romanians remained committed to the monarchy.[108] Other versions included a blue-white-red or blue-red-white arrangement, claimed by Alexandru Papiu Ilarian as "Transylvania's oldest colors", for being used in the Romanian dress.[109] This origin was also claimed by Ioan Pușcariu, who carried a version of the banner marked with a Romanian version of the slogan Liberté, égalité, fraternité. Pușcariu advocated for the blue-red-yellow of Transylvania and was told by his peers that the gold tassels could reflect that association.[110] Contrasting testimonies suggest that the arrangement was based on the flag of France,[111] or that it was improvised from the "Transylvanian colors [of] red and blue", with the white band as a symbol of peace.[112]

This "flag of the Transylvanian Romanians" was transformed into a red-blue-white, blue-red-white or white-blue-red tricolor, bearing the inscription VIRTUS ROMANA REDIVIVA ("Roman virtue revived").[113] The slogan's origin can be traced back to Romanian Grenz infantry regiments serving on the Transylvanian Military Frontier.[114] A blue-red-white variant was inscribed with VIRTUTEA ROMÂNĂ REÎNVIATĂ ("Romanian virtue revived"), and carried ribbons in the Habsburg colors, with a slogan honoring Ferdinand I.[115] Several authors note that such a color scheme merely reflected confusion among the Romanians, allowing Hungarians in the Diet to report that it was a pan-Slavic symbol.[44][110][116]

Over the following months, blue-yellow-red replaced other variants—either under the influence of flags used in the Wallachian revolution, or because yellow was a Habsburg color.[117] In Habsburg and Hungarian sources, this flag was depicted as a direct successor of the 1765 colors, indicating Romanian "autochtonism" after other Transylvanian communities had embraced ethnic flags.[118] This tricolor was paraded during the May assembly by the anti-Hungarian folk army gathered by Avram Iancu, and later flown by his guerrilla units throughout the Apuseni Mountains.[119] One variant, featuring an icon and tricolor bordure, is viewed by some historians as one of Iancu's battle flags.[120]

In January 1849, during the late stages of civil war in Transylvania, Ioan Axente Sever's Romanian irregulars who occupied and ransacked Straßburg (Aiud) flew the Habsburg bicolor.[121] Following the Hungarian revolutionaries' capitulation, Transylvania was more firmly integrated with the Austrian Empire, with the Székely seal being confiscated.[122] In late 1852, Transylvanian Governor Karl von Schwarzenberg ordered the reintroduction of a regional flag, but used an incorrect color scheme, switching the blue and red bands.[44] Various authors describe this as a conscious variation on the Romanian tricolor, meant to underline the connection between the monarchy and loyalist Romanians; the tricolor scheme was also granted to Reichsfreiherr Andrei Șaguna.[123]

During the subsequent reconciliation between Hungarians and Austrians, Transylvania was merged back into Hungary. This process, which included restoring heraldic symbols to the Székely nation in June 1861,[124] was resisted by Romanians. In 1862, ASTRA Society for Cultural Advancement staged an exhibit and political rally, which included tricolor flags and a tapestry with the Transylvanian arms protected by a lion, alongside the slogan INDEPENDENȚA TRANSILVANIEI ("Independence for Transylvania").[125]

In July 1863, Romanian members of the Transylvanian Diet presented a draft law "on the equality of the various nationalities". Its Article 5 specified that: "A symbol particular to the Romanian nation shall be added to the Transylvanian arms."[126] Subsequently, as a result of proposals of Transylvanian Diet, Franz Joseph drafted a decree granting freedom to all nationalities of the Austrian Empire and asking for the introduction of a Romanian symbol on the coat of arms and flag of Transylvania.[127] During the elections of late 1865, Romanians gathering to oppose centralization reportedly flew a large flag "in Transylvania's colors"; their Hungarian opponents used the red-white-and-green.[44]

Outside Transylvania, Romanian activists were more accepting of the 1765 arms, which were featured, alongside the Moldavian and Wallachian shields, on the medal Norma, issued by Wallachia's Philharmonic Society in 1838.[128] Cezar Bolliac gave this arrangement a colored version in 1856, selecting tinctures that would reflect the Romanian tricolor, with Transylvania in yellow (or).[129] Upon the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859, Transylvanian emblems were left out of the national arms. The presence of a "Dacian" woman and lions in supporters in all Romanian national arms between 1866 and 1872 was an homage to the 1848 proposal.[130]

.svg.png) One of the Romanian Transylvanian tricolor schemes used in 1848 (with Habsburg ribbons)

One of the Romanian Transylvanian tricolor schemes used in 1848 (with Habsburg ribbons).svg.png) Arms of Transylvania (top right) marshaled into the coat of arms of the Hungarian State (1849)

Arms of Transylvania (top right) marshaled into the coat of arms of the Hungarian State (1849) Variant of Austrian arms in 1850

Variant of Austrian arms in 1850 Flag reportedly endorsed by Karl von Schwarzenberg (1852)

Flag reportedly endorsed by Karl von Schwarzenberg (1852)

Austria-Hungary

.svg.png)

Transylvanian symbols were again added to the medium coat of arms of Hungary following the establishment of Austria-Hungary in 1867.[131] They were also prominently marshalled into in the amalgamated state arms of Austria-Hungary.[132] The subsequent centralization cancelled all need for regional symbols, which were relegated to a ceremonial role.[133] The informal Transylvanian flag was again recorded as "blue, red and yellow" in the late 1860s, with prints issued by the Armenian Zacharias Gábrus.[134] This version was also carried by Antal Esterházy at Franz Joseph's coronation in June 1867—the first-ever appearance of Transylvanian symbols at the enthronement of a Hungarian Habsburg king.[135] Two months later, the coat of arms was on show at the Romanian Literary Society in Bucharest. Though intended to show the cultural unity between Romanians within and without Austria-Hungary, this exhibit was criticized by nationalist writer Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu for still describing regional divisions between Transylvanian, Wallachian, and Moldavian Romanians.[136]

The regional flag was still flown at various festivities, though its interpretation varied between Romanians and Hungarians. The "Romanian, that is to say Transylvanian flag" and the Habsburg flag were reportedly used together at Maypole dances in Kronstadt by 1881. That year, a Hungarian tricolor and a "Saxon flag" were added; the former's appearance led to a publicized brawl, with claims that Romanian students had put up the national flag of another country.[137] Over that decade, Romanians continued to argue that the Transylvanian tricolor was a cherished symbol, but regional rather than ethnic. In 1885, the community newspaper Tribuna expressed indignation at Hungarian suggestions that the Romanian state tricolor was a derivative of Transylvania's color scheme.[138] The same year, the Romanian Athletic and Singing Society had adopted emblems with the "Transylvanian tricolor".[139]

Around the same time, Hungarian authorities banned the flying of any foreign flag, frustrating Romanian attempts to rally around a nationalist symbol. This led to another incident in June 1888, when the Romanians of Belényes (Beiuș) removed and desecrated the Hungarian national flag.[140] In the aftermath, the community was ordered by government to cease flying the Transylvanian colors.[141] No flags were on show during Franz Joseph's tour of Beszterce-Naszód in 1891, after local Hungarians explicitly rejected either a "Saxon flag" or the "Romanian tricolor, which is also Transylvania's flag".[142] In 1892, Romanian youth gathering at Nagyszeben (Sibiu) defied the ban by flying three separate monochrome flags of red, yellow, and blue.[143]

Transylvanian regional symbols were sometimes reclaimed by other members of the Hungarian community. In May 1896, during celebrations of the Hungarian Millennium, András Bethlen presented the regional colors to Franz Joseph; some Romanians and Saxons also took part, carrying "millennial flags" representing their various civic communities.[144] The color scheme also spread into the Duchy of Bukovina, a Romanian-inhabited part of Cisleithania, where it was identified and repressed as a symbol of "anti-Austrian" subversion. Before deciding on this issue, Governor Bourguignon heard reports about flag usage among the Transylvanian loyalists; his panel of experts disagreed on whether the flag was a Transylvanian symbol or a derivation of Romania's flag, but most viewed it as a staple of pan-Romanian "irredentism".[145]

In 1903, Romanian lawyer Eugen Lemeni was fined and imprisoned for decorating a ballroom hall with Habsburg flags and the "Transylvanian emblem".[146] During the Hungarian elections of 1906, the Romanian National Party (PNR) used white flags with green-leaf patterns, as well as green cockades, but these were also confiscated by the authorities.[147] The Romanian (and Transylvanian) colors were camouflaged into another symbolic arrangement: the PNR distributed lapels with a blue quill and a yellow leaf, adding candidates' names in red letters.[148] During those years, Romanian nationalist clubs began using an array of heraldic symbols evoking Dacia and the Romans.[149] At that stage, Saxon activists who similarly frowned upon Magyarization created their own regional symbol: a flag bearing the old triquetra and the slogan AD RETINENDAM CORONAM ("To protect the crown"), originally depicted in a highly popular print by Georg Bleibtreu (1884).[150] Other groups of Saxons used blue-red banners and ribbons with the Transylvanian arms—as with the Association of Transylvanian Saxons in Munich, founded in 1910.[151]

Writing shortly after the Millennium, Sterca-Șuluțiu proposed that the Transylvanian tinctures and the Romanian flag had a single, "Dacian" and "twice-millennial" origin—though he admitted not being able to tell why Maria Theresa had selected them.[44] He acknowledged that nationalist Romanians in both Transylvania and Bukovina had been using the 1765 color scheme as an excuse to fly the Romanian colors, but also that this practice was dying out under Hungarian pressures.[44] In 1901, the theory according to which the Romanian tricolor originated with the Transylvanian flag was reviewed as "seductive" and "probable" by Romanian journalist Constantin Berariu.[152] It was embraced by Ștefan Cicio Pop, who, in late 1910, used it to defend flag-wavers arrested in Fehér County.[153]

In August 1911, a large Romanian meeting was again hosted by Blaj, in this instance convened by ASTRA. The Hungarian authorities of Fehér were convinced to participate, taking seat under a tapestry showing en eagle and tower alongside the "Transylvanian tricolor: blue, yellow and red [sic]."[154] ASTRA's other symbols were all-blue banners marked with the names of its sections, or generic slogans.[155] Delegate Horia Petra-Petrescu also proposed an all-white flag marked BLAJ, which, he argued, was enough of a symbol for the Romanian communities.[156] The tricolor ambiguity was retained during the celebrations of May 10, 1914, when Romanian students gathered to celebrate the Kingdom of Romania's national holiday. Hungarian authorities broke up the rallies, citing the aggravating presence of Romanian colors. The students were defended by Pop, who claimed that the suspicious color scheme could just as well stand for Transylvania or Budapest.[157]

Over the following months, with the outbreak of World War I, the Common Army tolerated the use of Romanian banners by Transylvanian conscripts. Although Romania remained neutral until 1916, Hungarian authorities again introduced proscriptions against the Romanian colors in February 1915.[158] In October of that year, a revamped version of the Hungarian arms, with minor adjustments to its Transylvanian quarter, was done by József Sebestyén Keöpeczi, a Transylvanian Hungarian scholar and painter.[159] With the crowning of Charles IV in November 1916, Transylvanian colors made a final official appearance at the Habsburg court, being carried there by Count Ádám Teleki.[160] According to Moisil, under Charles the region was no longer depicted in the Hungarian coat of arms, but was still represented within the amalgamated Austro-Hungarian arms.[161]

Arms variant by Hugo Gerard Ströhl

Arms variant by Hugo Gerard Ströhl.jpg) Arms as depicted in the Hungarian Parliament Building (1904)

Arms as depicted in the Hungarian Parliament Building (1904) Romanian Cobblers' Guild banner (1867)

Romanian Cobblers' Guild banner (1867)

1918 union and later usage

Following the Aster Revolution of 1918, Transylvanian Romanians began organizing themselves to demand union with Romania, flying horizontal tricolors of blue-yellow-red.[162] Many variants of these were used during the popular rallies on the date marked in Romania as Great Union Day (December 1, 1918).[163] Eyewitness Petru Tămâian described these as being the "beautiful Transylvanian tricolor", distinguishing them from the vertically arranged flag of Romania; when superimposed, they "seemingly create a sign of the cross, symbolizing sufferings on both sides".[164] Attempts to restore an independent Transylvania were still considered by a Hungarian jurist, Elemér Gyárfás. In March 1919, he approached the PNR's Iuliu Maniu with the offer to codify an "indissoluble union of three nations" (Transylvanian Romanians, Hungarians, and Saxons). This proposed state was to have its own seal and flag.[165]

As part of the subsequent union process in 1918–1922, Transylvania's symbols became an integral part of the Romanian arms. The 1921 design, proposed to the Heraldic Commission by Keöpeczi,[166] was closely based on Maria Theresa's arms of 1765.[167] Under the new conventions, it was also used to symbolize the adjacent lands of Maramureș and Crișana.[168] Transylvania's arms were also cherished by Hungarian irredentism during the Regency period. Also in 1921, a statue called "East" was erected in Szabadság tér, Budapest. It showed Prince Csaba setting free a female figure bearing the Transylvanian shield.[169] The medium arms of 1915 were still endorsed by the Regency, but for two decades appeared only rarely on its official insignia; usage again peaked in 1938–1944.[170]

At the height of World War II, following a re-partition of the region, Northern Transylvania was briefly reincorporated with Hungary. A new set of monuments, featuring the eagle together with the medium arms of Hungary, was erected throughout the annexed areas.[171] During this interval, Béla Teleki and other local intellectuals established a regionalist and corporatist group called Transylvanian Party; it did not use the regional flag and coat of arms, but had a depiction of Saint Ladislaus as its logo.[172] Arms with a Transylvanian canton remained a Romanian national symbol throughout this period, until being removed by communist rule (see Emblem of the Socialist Republic of Romania). The regime involved itself in removing signs of Hungarian irredentism, such as plastering over the medium Hungarian arms on the 1941 monument in Lueta (Lövéte). It was cleaned up by community representatives during the Romanian Revolution of 1989.[173]

The 1921 arms were reinstated, with some modifications, under the 1992 Constitution, and were again reconfirmed in 2016.[174] Following the revival of heraldry in post-communist Romania, azure and gules, identified as the "Transylvanian colors", were used for the new arms of Miklós Székely National College; Simeria Reformed Church in Sfântu Gheorghe also features a 1992 mural with the 1765 arms of Transylvania.[175] In 1996, the municipality of Ozun (Uzon) displayed the same symbol at an artificial forest which celebrated Hungarian presence in Transylvania and commemorated the soldiers of 1848.[176] The Saxon diaspora in Germany has also continued to make use of regional symbols. In the 1990s, those who settled in Crailsheim still displayed the "Transylvanian" or "Saxon colors", described as "blue and red".[177] Usage of the flag and coat of arms was being replaced around 2017 by displays of the logo for the Union of Transylvanian Saxons in Germany.[178]

At the same stage, a Székely autonomist movement had begun using its own derivative symbol—the blue-gold-silver flag with the sun-and-moon.[179] A blue-red-yellow tricolor is also spotted at rallies in support of increased autonomy for the region or its Hungarian communities. A controversy erupted on Hungarian National Day (March 15), 2017, after reports that the Romanian Gendarmerie fined people for displaying the colors. This account was rejected by Gendermerie officials, according to whom the fines were handed out to those demonstrators who refused to disperse after their authorization had expired.[180] Transylvanian symbols, including the coat of arms, have been on display at football matches involving CFR Cluj, which has a mixed Romanian-and-Hungarian fan base.[181]

.svg.png) Flag used on Great Union Day 1918

Flag used on Great Union Day 1918 Arms used by Saxon cultural bodies

Arms used by Saxon cultural bodies Flag of the Szekler National Council

Flag of the Szekler National Council.svg.png) Unofficial flag variant, used locally in Transylvania

Unofficial flag variant, used locally in Transylvania

References

Citations

- Cernovodeanu, p. 129

- Byron McCandless, Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor, Flags of the World, pp. 370, 399. Washington, D. C.: National Geographic Society, 1917

- Marțian, pp. 443–445

- Cernovodeanu, p. 131

- Marțian, p. 442

- Tiron (2011), pp. 312–313

- Tiron (2011), pp. 312–313, 315–318, 336

- Tiron (2011), pp. 313–314, 335–337

- Tiron (2006), p. 218

- Cernovodeanu, p. 93

- Tiron (2006), pp. 221–223

- Marțian, p. 443

- Szekeres (2017), pp. 12–25. See also Borsos, p. 52; Marțian, p. 445; Pál-Antal, pp. 9–13

- Borsos, p. 52; Marțian, pp. 441, 445; Pál-Antal, pp. 9–13; Szekeres (2017), pp. 13–14, 16–17

- Marțian, pp. 445–446

- Cernovodeanu, p. 129; Moisil, pp. 72–73

- Marțian, p. 441; Pál-Antal, pp. 13–15; Tiron (2011), p. 318

- Ardelean, pp. 195, 197, 203

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 73, 130. See also Tiron (2011), pp. 312, 322–323

- Tiron (2011), pp. 318–323

- Tiron (2011), pp. 311, 319, 322–323. See also Cernovodeanu, p. 131; Iftimi, p. 192; Marțian, pp. 443–444

- Cătălin Pungă, "'Planul dacic' al lui Ioan Iacob Heraclid Despot (1561–1563)", in Ioan Neculce. Buletinul Muzeului de Istorie a Moldovei, Vol. XIX, 2013, pp. 94–95

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 130–131; Tiron (2011), pp. 310, 337–338

- de Gérando, p. 235

- Ardelean, pp. 203–205

- Tiron (2006), pp. 220–221, 227, 230

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 129, 130–131; Tiron (2011), p. 337

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 133–134; Tiron (2011), pp. 308–310, 337. See also Pál-Antal, p. 17; Szekeres (2017), p. 26

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 131–133; Moisil, pp. 76–77; Pál-Antal, p. 17; Szekeres (2017), pp. 26–27; Tiron (2011), pp. 310, 324–335

- Cernovodeanu, p. 133

- Moisil, p. 74

- Cernovodeanu, p. 133

- Ștefan Andreescu, "Comerțul danubiano-pontic la sfârșitul secolului al XVI-lea: Mihai Viteazul și 'drumul moldovenesc'", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, Vol. XV, 1997, p. 43; Nicolae Iorga, "Note despre vechea Bucovină", in Revista Istorică, Vol. I, Issue 5, May 1915, pp. 86–87

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 131–134; Tiron (2011), pp. 310–311, 338

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 132, 133

- Cernovodeanu, p. 133

- Marțian, p. 443

- Tiron (2011), pp. 311–313

- Tiron (2011), pp. 330–331, 338

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 69–73. See also Moisil, p. 78

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 72–73, 134

- Szekeres (2017), pp. 24–25

- Tiron (2011), p. 338

- Iosif Sterca-Șuluțiu, "Tricolorul românesc. (Fine.)", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 206/1910, p. 2

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 73, 134

- Cernovodeanu, p. 134

- Tiron (2006), p. 226. See also Moisil, p. 74

- Marțian, p. 442

- Moisil, p. 74

- Tiron (2006), p. 233

- Cernovodeanu, p. 135; Szekeres (2017), pp. 31–32

- János Mihály, "Bethlen Gábor fejedelemzászlóiról", in Örökségünk, Issue 2/2014, p. 9

- Vencel Bíró, Erdély követei a portán, p. 104. Cluj: Minerva, 1921

- Cernovodeanu, p. 135; Szekeres (2017), pp. 32–35

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 136–137

- Mirela Cărăbineanu, "Hârtia în Cancelaria princiară a Transilvaniei. Câteva aspecte privind filigranele", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie George Barițiu. Series Historica, Supplement 1: "Literacy Experiences Concerning Medieval and Modern Transylvania", 2015, pp. 357–359

- Szidónia Weisz, "Ars heraldica. Heraldica lui Pápai Páriz Ferenc", in Libraria. Studii și Cercetări de Bibliologie, Vol. VIII, 2009, [n. p.]

- Tiron (2006), pp. 227–229

- Borsos, pp. 52–53; Cernovodeanu, pp. 134–136; Pál-Antal, pp. 13–15, 17–20; Szekeres (2017), pp. 40–42

- Cernovodeanu, p. 136; Marțian, p. 441; Pál-Antal, p. 18; Szekeres (2017), pp. 40–42

- Cernovodeanu, p. 136; Pál-Antal, pp. 14–15; Szekeres (2017), p. 42

- Mihaela Mehedinți, "Transylvanian Identities: Swedish Travellers' Observations for the 17th–19th Centuries Realities [sic]", in Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai. Historia, Vol. 57, Special Issue, December 2012, pp. 50–51

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 134–136; Marțian, pp. 441–443; Moisil, p. 74; Pál-Antal, pp. 13–15, 17–20; Papoiu & Căpățînă, p. 198; Popescu, p. 197; Szekeres (2017), pp. 40–42

- Marțian, pp. 441–443

- Pál-Antal, pp. 13–15; Szekeres (2017), pp. 40–42

- Moisil, p. 74

- Moisil, p. 75

- Iftimi, pp. 191–192

- Constantin Iconomu, "Noi date arheologice despre județul Vaslui rezultate dintr-o donație", in Arheologia Moldovei, Vols. XXIII–XXIV, 2000–2001, p. 278

- de Gérando, pp. 134–135

- Cernovodeanu, p. 137

- Szekeres (2017), pp. 42–45. See also Borsos, pp. 53–54; Kirițescu, p. 105

- Phillips, pp. 53, 89, 111

- Papoiu & Căpățînă, pp. 197–198

- György Antal Diószegi, "Zászlótartó hõseink az 1848–49. évi dicsõséges magyar szabadságharc csatáiban", in ARACS, Vol. XIV, Issue 1, 2014, p. 25

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 137–138. See also Szekeres (2017), p. 14

- Marțian, pp. 443–444

- Borsos, pp. 54–55; Cernovodeanu, p. 137

- Cernovodeanu, p. 138

- Borsos, p. 52; Cernovodeanu, p. 138; Moisil, p. 75

- Borsos, pp. 52–55; Szekeres (2017), p. 46

- Berariu I, pp. 1, 3 & II, p. 4; Olaru, p. 391

- Lupaș, pp. 355–356; Szabo, p. 333

- Szabo, pp. 333–334

- Lupaș, p. 356

- Serbările, pp. 70, 345, VIII

- Papoiu & Căpățînă, p. 198

- Rolf Kutschera, "Guvernatorii Transilvaniei, 1691—1774", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie Națională, Vol. IX, 1943–1944, pp. 182–184

- Moisil, p. 75

- Ștefan Pascu, "Știri noui privitoare la revoluțiunea lui Horia", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie Națională, Vol. IX, 1943–1944, p. 361

- Ioan C. Băcilă, "Portretele lui Horia, Cloșca și Crișan", in Transilvania, Vol. LIII, Issue 1, January 1922, pp. 22–23, 29–31, 46, 48–52, 60–61; Paula Virag, "'Horea – Rex Daciae' – Considerations on the Numismatic Symbols of the Peasants' Uprising of 1784–1785", in Acta Mvsei Napocensis. Series Historica, Vol. 52, Issue II, 2015, pp. 81–89

- Marin Sâmbrian-Toma, "Carte veche de istorie din anii 1791–1828 în colecții din Craiova", in Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Historica, Vol. XII, 2008, pp. 152–153

- Phillips, p. 54

- de Gérando, p. 152

- Kirițescu, pp. 104, 105

- "Fișele exponatelor", in Valeriu Cavruc, Andrea Chiricescu (eds.), Sarea, Timpul și Omul. Catalog de expoziție, pp. 245–246. Sfântu Gheorghe: Editura Angustia, 2006. ISBN 973-85676-8-8

- Cernovodeanu, p. 138

- Cernovodeanu, p. 138

- de Gérando, pp. 51–54

- Forró, p. 329

- Katalin Ágnes Bartha, "Theatre Inauguration Ceremony and Symbolic Representation", in Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai. Dramatica, Vol. XII, Issue 2, 2017, pp. 29–31

- Minerva Nistor, "Brașovul în izvoare cartografice și iconografice", in Cumidava, Vol. IV, Issue IX (Part 1), 1970, pp. 55–56

- Borsos, pp. 55–56

- Alexandru Ceușianu, "Vremuri de osândă. Revoluția 1848/49 din perspectiva unui orășel ardelenesc ", in Țara Bârsei, Vol. VI, Issue 4, July–August 1934, pp. 321–322

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 139, 150; Dogaru, pp. 449–450

- Cernovodeanu, p. 150

- Pălănceanu, pp. 139–142

- Sbiera, p. 219; Teșculă & Gavrilă, pp. 204–205

- Pălănceanu, p. 139; Sbiera, p. 219. See also Berariu I, p. 3; Olaru, pp. 390, 393

- Ioan Pușcariu, "Adunarea națională din 3/15 Maiu 1848", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 130/1913, p. 3

- Berariu I, p. 2; Neagu, p. 318

- Camil Mureșanu, "Adunarea națională de la Blaj. Relatări din presa vremii", in Acta Mvsei Porolissensis, Vol. XXX, 2008, p. 280

- Berariu I, p. 3; Neagu, p. 318; Olaru, p. 393; Sbiera, p. 219

- Berariu I, p. 3; Sbiera, p. 219

- Teșculă & Gavrilă, p. 205

- Berariu I, p. 3

- Olaru, pp. 390, 392–393; Sbiera, pp. 219–221

- Olaru, p. 391

- Pălănceanu, pp. 139–142. See also Berariu I, p. 3

- (in Romanian) "Drapelul lui Avram Iancu nu este al lui Avram Iancu", in Monitorul de Cluj, January 28, 2016; Raluca Ion, Diana Pârvulescu, "A fost sau n-a fost. Povestea steagului "lui Avram Iancu", care a pus ministerul Culturii pe jar", in Gândul, October 24, 2013

- Valer Rus, "Războiul civil ardelean (1848–1849) și petițiile văduvelor maghiare", in Țara Bârsei, Vol. XIII, Issue 13, 2014, pp. 45, 58, 61–62

- Pál-Antal, p. 20

- Berariu I, p. 1 & II, p. 3; Neagu, p. 318

- Pál-Antal, pp. 20–21

- Gherghina Boda, "Expoziția națională a Astrei de la Brașov (1862)", in Țara Bârsei, Vol. 11, 2008, pp. 97–99

- "Nouvelles étrangères. Autriche. Hermannstadt (Transylvanie), 27 juillet", in Journal des Débats, August 4, 1863, p. 1

- Simion Retegan, "'Epoca care surâde': Românii în anii liberalismului habsburgic, 1860–1865", în Grigor Pop (ed.), Istoria României. Transilvania, Vol. I, pp. 987–1175. Cluj-Napoca: Editura George Barițiu, 1997

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 22, 141

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 22–23, 139

- Cernovodeanu, pp. 139, 155; Dogaru, p. 450

- Borsos, p. 56; Moisil, p. 75; Szekeres (2017), pp. 46–47

- Phillips, p. 54

- Moisil, p. 75; Pál-Antal, p. 21

- Ioan Chindriș, Anca Elisabeta Tatay, "An Armenian Man of Culture and Artist from Transylvania. Zacharias Gábrus (Zacharija Gabrušjan) and His Heraldic Manuscript", in Series Byzantina. Studies on Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art, Vol. IX (Art of the Armenian Diaspora. Proceedings of the Conference, Zamość, April 28–30, 2010), 2011, p. 143

- Pálffy, pp. 35, 37. See also Berariu I, p. 1

- Vasile Maciu, "Un pasionat luptător pentru Unire: B. P. Hasdeu", in Magazin Istoric, April 1970, p. 26

- Un Brașovean, "Corespondențe particulare ale Telegrafului Român. Brașov, 18 Maiu", in Telegraful Român, Issue 59/1881, p. 235

- "Sibiiu, 19 Decemvrie st. v.", in Tribuna, Issue 200/1885, p. 1

- "Sfințirea stégului Reuniunii române de gimnastică și cântări din Brașov", in Familia, Issue 47/1885, pp. 560–561

- Neș, pp. 168–170, 345, 355, 451

- V., "Corespondențe particulare ale Telegrafului Român. Steagul din Beiuș", in Telegraful Român, Issue 65/1888, pp. 260–261

- Raport, "Corespondințe. Manevrele militare în Bistrița", in Unirea. Fóia Bisericéscă-Politică, Issue 38/1891, pp. 299–300

- "Din pildele trecutului. D-l Vaida-Voevod despre tineri și bătrâni", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 99/1936, p. 1

- Rozalinda Posea, "O festivitate publică controversată, sărbătoarea Milleniului", in Țara Bârsei, Vol. X, Issue 10, 2011, p. 117

- Olaru, pp. 387–392

- "Cronică. O nouă condamnare", in Foaia Poporului, Issue 11/1903, p. 129

- Neș, pp. 200, 400–401

- Neș, p. 401

- Dogaru, pp. 450–453

- Konrad Klein, "'... Seine Kunst in den Dienst unserer Nationalen Sache gestellt'. Anmerkungen zu Georg Bleibtreus Historienbild 'Die Einwanderung der Sachsen nach Siebenbürgen und die Gründung von Hermannstadt'", in Ioan Marin Țiplic, Konrad Gündish (eds.), Sașii și concetățenii lor ardeleni / Die Sachsen und ihre Nachbarn in Siebenbürgen. Studia in Honorem Dr. Thomas Nägler, pp. 287–298. Alba Iulia: Altip, 2009. ISBN 978-973-117-213-2

- (in German) Christian Schoger, "Vereinsgründung in München vor 106 Jahren", in Siebenbürgische Zeitung, March 20, 2004

- Berariu I, p. 2 & II, pp. 3, 4

- "Din dietă", in Foaia Poporului, Issue 48/1910, p. 2

- Serbările, p. 414

- Serbările, pp. 3, 63, 277, 405

- Serbările, p. 128

- "Interpelația dlui Dr. Ștefan C. Pop în chestia disolvării adunării poporale dela Alba Iulia (Continuare)", in Românul (Arad), Issue 120/1914, p. 4

- Costin Scurtu, "Știri de pe frontul bucovinean în România (1914–1918)", in Țara Bârsei, Vol. XIII, Issue 13, 2014, pp. 133, 135–136

- Borsos, p. 56

- Pálffy, p. 35

- Moisil, p. 75

- Neagu, p. 319; Neș, pp. 520–521, 527, 566; Pălănceanu, pp. 142–143

- Pălănceanu, pp. 142–143; Tămâian, passim

- Tămâian, p. 15

- Károly Gulya, "Az erdélyi nemzetiségi kérdés megoldására irányuló törekvések 1918–1919-ben", in Acta Universitatis Szegediensis. Acta Historica, Vol. 9, 1961, pp. 11–12

- Szekeres (2013), p. 288 & (2017), p. 47

- Cernovodeanu, p. 139. See also Marțian, p. 446

- Moisil, pp. 83–84; Popescu, p. 197

- Miklós Zeidler, "Irredentism in Everyday Life in Hungary during the Inter-war Period", in Regio. A Review of Studies on Minorities, Politics, and Society, 2002, p. 73

- Borsos, p. 56

- Forró, pp. 327–329

- Gábor Egry, "Minority Elite, Continuity, and Identity Politics in Northern Transylvania: The Case of the Transylvanian Party", in Victor Karady, Borbála Zsuzsanna Török (eds.), Cultural Dimensions of Elite Formation in Transylvania (1770–1950), pp. 186–215. Cluj-Napoca: Ethnocultural Diversity Resource Center, 2008. ISBN 978-973-86239-6-5

- Forró, p. 328

- Szekeres (2017), p. 47. See also Popescu, pp. 196–197

- Szekeres (2013), p. 288, 290–291

- György Beke, "Sorskérdések. Fáklya-sors. Egy székely tanár portréjához", in Honismeret, Issue 1/1999, p. 51

- "Das 9. Tartlauer Treffen vom 26. Sept. '98 in Schnelldorf bei Crailsheim", in Das Tartlauer Wort, Issue 33/1998, p. 2

- Hermanik, pp. 221–222

- Hermanik, pp. 119–120, 202

- (in Hungarian) Csaba Gyergyai, Andrea Kőrössy, "Zászlóügy: egymásra mutogatnak. Több ízben is az Erdély-lobogó felcsavarását kérték akolozsvári március 15-ei megemlékezés szervezői", in Udvarhelyi Híradó, March 17–19, 2017, p. 7

- Péter Csillag, "Kolozsvári futballmítoszok – Egy rejtőzködő klubjellemrajza, a valós és vélt kötődések szerepea CFR 1907 Cluj magyarországi megítélésében", in Erdélyi Társadalom, Vol. 13, Issue 2, 2015, p. 175

Sources

- Serbările dela Blaj. 1911. O pagină din istoria noastră culturală. Blaj: Despărțământul XI. Blaj, al Asociațiunii & Tipografia Seminarului Teologic Gr. Cat., 1911.

- Florin Ardelean, "Obligațiile militare ale nobilimii în Transilvania princiară (1540–1657)", in Revista Crisia, Vol. XL, 2010, pp. 193–208.

- Constantin Berariu, "Tricolorul românesc", in Gazeta Transilvaniei: Part I, Issue 94/1901, pp. 1–3; Part II, Issue 100/1901, pp. 2–4.

- András Imre Borsos, "A félhold képe Erdély címerében", in Honismeret, Issue 3/1991, pp. 52–56.

- Dan Cernovodeanu, Știința și arta heraldică în România. Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1977. OCLC 469825245

- Auguste de Gérando, La Transylvanie et ses habitants. Paris: Comptoir des imprimeurs unis, 1845.

- Maria Dogaru, "Insignes et devises héraldiques attestant l'origine latine du peuple roumain", in A. d'Addano, R. Gueze, A. Pratesi, G. Scalia (eds.), Studi in onore di Leopoldo Sandri. II (Publicazioni degli Archivi di Stato, XCVIII. Saggi I), pp. 443–455. Rome: Ministry for Cultural Assets and Environments & Casa Editrice Felice Le Monnier.

- Albert Forró, "Első világháborús emlékművek Udvarhely megyében", in Areopolisz. Történelmi és Társadalomtudományi Tanulmányok, Vol. VII, 2007, pp. 315–336.

- Klaus-Jürgen Hermanik, Deutsche und Ungarn im südöstlichen Europa. Identitäts- und Ethnomanagement. Böhlau Verlag: Vienna etc., 2017. ISBN 978-3-205-20264-6

- Sorin Iftimi, Vechile blazoane vorbesc. Obiecte armoriate din colecții ieșene. Iași: Palatul Culturii, 2014. ISBN 978-606-8547-02-2

- Costin Kirițescu, Sistemul bănesc al leului și precursorii lui, Volume I. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1964.

- Ioan Lupaș, "Miscellanea. Mitul 'Sacrei Coroane' și problema transilvană", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie Națională, Vol. VIII, 1939–1940, pp. 343–360.

- Iulian Marțian, "Contribuții la eraldica vechiului Ardeal", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie Națională, Vol. IV, 1926–1927, pp. 441–446.

- Constantin Moisil, "Stema României. — Originea și evoluția ei istorică și heraldică", in Boabe de Grâu, Issue 2/1931, pp. 65–85.

- Doru Neagu, "Din istoricul drapelului național", in Argesis. Studii și comunicări. Seria Istorie, Vol. XIX, 2010, pp. 315–320.

- Teodor Neș, Oameni din Bihor: 1848–1918. Oradea: Tipografia Diecezană, 1937.

- Marian Olaru, "Lupta pentru tricolor și afirmarea identității naționale românești în Bucovina", in Analele Bucovinei, Vol. VI, Issue 2, 1999, pp. 387–406.

- Sándor Pál-Antal, "Sigiliul 'Națiunii' secuiești", in Anuarul Arhivelor Mureșene, Vol. III, 2014, pp. 9–24.

- Elena Pălănceanu, "Steaguri din colecția Muzeului de Istorie al Republicii Socialiste România", in Muzeul Național, Vol. I, 1974, pp. 135–155.

- Géza Pálffy, "Koronázási országzászlókés zászlóvivő főnemesek", in Rubicon, Issues 1–2/2017, pp. 31–37.

- Lizica Papoiu, Dan Căpățînă, "O diplomă de înnobilare (secolul al XVIII-lea) din Țara Crișului Alb", in Muzeul Național, Vol. VI, 1982, pp. 196–199.

- David F. Phillips, The Double Eagle (The Flag Heritage Foundation Monograph and Translation Series, Publication No. 4). Danvers: Flag Heritage Foundation, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4507-2430-2

- Vlad-Lucian Popescu, "Considerații cu privire la stema de stat a României și cea a Republicii Moldova", in Revista Erasmus, Issue 12/2001, pp. 196–199.

- Ion G. Sbiera, "Ceva despre tricolorul român", in Calendarul Minervei pe Anul 1905, pp. 218–227.

- Franz Szabo, Kaunitz and Enlightened Absolutism 1753–1780. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-46690-3

- Attila István Szekeres,

- "Renașterea fenomenului heraldic la Sf. Gheorghe după anul 1989", in Acta Terrae Fogorasiensis, Vol. II, 2013, pp. 285–304.

- "Stema comunității secuiești", in Attila István Szekeres, Sándor Pál-Antal, János Mihály (eds.), Simboluri istorice secuiești, pp. 11–69. Odorheiu Secuiesc: Centrul Județean pentru Conservarea și Promovarea Culturii Tradiționale Harghita, 2017. ISBN 978-606-93980-8-1

- Petru Tămâian, "'Mărire Ție Celui ce ne-ai arătat nouă lumina!'", in Vestitorul, Issues 9–10/1929, pp. 15–16.

- Nicolae Teșculă, Gheorghe Gavrilă, "Marea Adunare Națională de la Blaj din 3/15 mai 1848 într-o descriere inedită a unui memorialist sighișorean", in Revista Bistriței, Vol. XVII, 2003, pp. 201–206.

- Tudor-Radu Tiron,

- "Despre dreptul la stemă în Transilvania secolului XVII", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, Vol. XXIV, 2006, pp. 217–238.

- "Începuturile stemei Transilvaniei în lumina mai multor izvoare ilustrate externe, din secolul al XV-lea până la începutul secolului al XVII-lea", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie George Barițiu. Series Historica, Vol. L, 2011, pp. 307–339.