Civil uprising phase of the Syrian Civil War

The civil uprising phase of the Syrian Civil War, or as it was sometimes called by the media, the Syrian Revolution,[20] was an early stage of protests – with subsequent violent reaction by the Syrian Arab Republic – lasting from March to 28 July 2011. The uprising, initially demanding democratic reforms, evolved from initially minor protests, beginning as early as January 2011 and transformed into massive protests in March.

The uprising was marked by massive anti-government opposition demonstrations against the Ba'athist government led by Bashar al-Assad, meeting with police and military violence, massive arrests and a brutal crackdown, resulting in hundreds of deaths and thousands of wounded.

Despite Bashar al-Assad's attempts to stop the protests with the massive crackdown and use of censorship on one hand and concessions on the other, by the end of April it became clear the situation was getting out of his control and his government deployed numerous troops on the ground.

The civil uprising phase led to the emergence of militant opposition movements and massive defections from the Syrian Army, which gradually transformed the conflict from a civil uprising to an armed rebellion, and later a full-scale civil war. The rebel Free Syrian Army was created on 29 July 2011, marking the transition into armed insurgency.

Background

Before the uprising in Syria began in mid-March 2011, protests were relatively modest, considering the wave of unrest that was spreading across the Arab world. Syria, until March 2011, for decades had remained superficially tranquil, largely due to fear among the people of the secret police arresting critical citizens.[21]

Factors contributing to social unrest in Syria include socioeconomic stressors caused by the Iraqi conflict (2003–present), as well as the most intense drought ever recorded in the region.[22]

Minor protests calling for government reforms began in January, and continued into March. At this time, massive protests were occurring in Cairo against Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, and in Syria on 3 February via the websites Facebook and Twitter, a "Day of Rage" was called for by activists against the government of Bashar al-Assad, to be held on Friday, 4 February.[23] This did not result in protests. [24] [25]

Civil uprising (March–July 2011)

March 2011 unrest

Major unrest began on 15 March in Damascus, yet in the southern city of Daraa, sometimes called the "Cradle of the Revolution",[26] protests had been triggered on 6 March by the incarceration and torture of 15 young students from prominent families who were arrested for writing anti-government graffiti in the city,[27][28][29] reading: "الشعب يريد إسقاط النظام" – ("The people want the fall of the regime") – a trademark slogan of the Arab Spring.[30][31] A 13-year-old boy, Hamza al-Khateeb, was tortured and killed.[32]

The government claimed that the boys weren't attacked, and that Qatar incited the majority of the protests.[33] Writer and analyst Louai al-Hussein, referencing the Arab Spring ongoing at that time, wrote that "Syria is now on the map of countries in the region with an uprising".[31] Demonstrators clashed with local police, and confrontations escalated on 18 March after Friday prayers. Security forces attacked protesters gathered at the Omari Mosque using water cannons and tear gas, followed by live fire, killing four.[34][35]

On 20 March, a mob burned down the Ba'ath Party headquarters and other public buildings. Security forces quickly responded, firing live ammunition at crowds, and attacking the focal points of the demonstrations. The two-day assault resulted in the deaths of seven police officers[36] and fifteen protesters.[37]

Meanwhile, minor protests occurred elsewhere in the country. Protesters demanded the release of political prisoners, the abolition of Syria's 48-year emergency law, more freedoms, and an end to pervasive government corruption.[38] The events led to a "Friday of Dignity" on 18 March, when large-scale protests broke out in several cities, including Banias, Damascus, al-Hasakah, Daraa, Deir az-Zor, and Hama. Police responded to the protests with tear gas, water cannons, and beatings. At least 6 people were killed and many others injured.[39]

On 25 March, mass protests spread nationwide, as demonstrators emerged after Friday prayers. At least 20 protesters were reportedly killed by security forces. Protests subsequently spread to other Syrian cities, including Homs, Hama, Baniyas, Jasim, Aleppo, Damascus and Latakia. Over 70 protesters in total were reported killed.[40]

Crackdown

Even before the uprising began, the Syrian government had made numerous arrests of political dissidents and human rights campaigners, many of whom were labeled "terrorists" by the Assad government. In early February 2011, authorities arrested several activists, including political leaders Ghassan al-Najar,[41] Abbas Abbas,[42] and Adnan Mustafa.[43]

Police and security forces responded to the protests violently, using water cannons and tear gas as well as physically beating protesters and firing live ammunition.[44]

As the uprising began, the Syrian government waged a campaign of arrests that captured tens of thousands of people, according to lawyers and activists in Syria and human rights groups. In response to the uprising, Syrian law had been changed to allow the police and any of the nation's 18 security forces to detain a suspect for eight days without a warrant. Arrests focused on two groups: political activists, and men and boys from the towns that the Syrian Army would start to besiege in April.[45] Many of those detained experienced ill-treatment. Many detainees were cramped in tight rooms and were given limited resources, and some were beaten, electrically jolted, or debilitated. At least 27 torture centers run by Syrian intelligence agencies were revealed by Human Rights Watch on 3 July 2012.[46]

President Assad characterized the opposition as armed terrorist groups with Islamist "takfiri" extremist motives, portraying himself as the last guarantee for a secular form of government.[47] Early in the month of April, a large deployment of security forces prevented tent encampments in Latakia. Blockades were set up in several cities to prevent the movement of protests. Despite the crackdown, widespread protests continued throughout the month in Daraa, Baniyas, Al-Qamishli, Homs, Douma and Harasta.[48]

Concessions

During March and April, the Syrian government, hoping to alleviate the unrest, offered political reforms and policy changes. Authorities shortened mandatory army conscription,[49] and in an apparent attempt to reduce corruption, fired the governor of Daraa.[50] The government announced it would release political prisoners, cut taxes, raise the salaries of public sector workers, provide more press freedoms, and increase job opportunities.[51] Many of these announced reforms were never implemented.[52]

The government, dominated by the Alawite sect, made some concessions to the majority Sunni and some minority populations. Authorities reversed a ban that restricted teachers from wearing the niqab, and closed the country's only casino.[53] The government also granted citizenship to thousands of Syrian Kurds previously labeled "foreigners".[54] Following Bahrain's example, the Syrian government held a two-day national dialogue in July, in attempt to alleviate the crisis. The dialogue was a chance to discuss the democratic reforms and other issues, however many of the opposition leaders and protest leaders refused to attend citing that continuing crackdown on protesters in streets.[55][56]

A popular demand from protesters was an end of the nation's state of emergency, which had been in effect for nearly 50 years. The emergency law had been used to justify arbitrary arrests and detention, and to ban political opposition. After weeks of debate, Assad signed the decree on 21 April, lifting Syria's state of emergency.[57] However, anti-government protests continued into April, with activists unsatisfied with what they considered vague promises of reform from Assad.[58]

Further reforms

During the course of the civil war, there have been some political changes towards the electoral process and the constitution.

Military operations

April 2011

_%D9%85%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%87%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA_%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B3_%D8%AC%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%BA%D8%B6%D8%A8_-_29_%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%86_2011.jpg)

As the unrest continued, the Syrian government began launching major military operations to suppress resistance, signaling a new phase in the uprising. On 25 April, Daraa, which had become a focal point of the uprising, was one of the first cities to be besieged by the Syrian Army. An estimated hundreds to 6,000 soldiers were deployed, firing live ammunition at demonstrators and searching house to house for protesters, slaughtering hundreds.[59] Tanks were used for the first time against demonstrators, and snipers took positions on the rooftops of mosques. Mosques used as headquarters for demonstrators and organizers were especially targeted.[59] Security forces began shutting off water, power and phone lines, and confiscating flour and food. Clashes between the army and opposition forces, which included armed protesters and defected soldiers, led to the death of hundreds.[60] By 5 May, most of the protests had been suppressed, and the military began pulling out of Daraa, with some troops remaining to keep the situation under control.

May 2011

During the crackdown in Daraa, the Syrian Army also besieged and blockaded several towns around Damascus. Throughout May, situations similar to those that occurred in Daraa were reported in other besieged towns and cities, such as Baniyas, Homs, Talkalakh, Latakia, and several other towns.[61] After the end of each siege, violent suppression of sporadic protests continued throughout the following months.[62] By 24 May, the names of 1,062 people killed in the uprising since mid-March had been documented by the National Organization for Human Rights in Syria.[63]

June–July 2011

As the uprising progressed, opposition fighters became better equipped and more organized. Until September 2011, about two senior military or security officers defected to the opposition.[64] Some analysts stated that these defections were signs of Assad's weakening inner circle.[65]

The first instance of armed insurrection occurred on 4 June 2011 in Jisr ash-Shugur, a city near the Turkish border in Idlib province. Angry protesters set fire to a building where security forces had fired on a funeral demonstration. Eight security officers died in the fire as demonstrators took control of a police station, seizing weapons. Clashes between protesters and security forces continued in the following days. Some security officers defected after secret police and intelligence agents executed soldiers who refused to kill the civilians. On 6 June, Sunni militiamen and army defectors ambushed a group of security forces heading to the city which was met by a large government counterattack. Fearing a massacre, insurgents and defectors, along with 10,000 residents, fled across the Turkish border.[37]

In June and July 2011, protests continued as government forces expanded operations, repeatedly firing at protesters, employing tanks against demonstrations, and conducting arrests. The towns of Rastan and Talbiseh, and Maarat al-Numaan were besieged in early June.[66] On 30 June, large protests erupted against the Assad government in Aleppo, Syria's largest city.[67] On 3 July, Syrian tanks were deployed to Hama, two days after the city witnessed the largest demonstration against Bashar al-Assad.[68]

During the first six months of the uprising, the inhabitants of Syria's two largest cities, Damascus and Aleppo, remained largely uninvolved in the anti-government protests.[69] The two cities' central squares have seen organized rallies of hundreds of thousands in support of president Assad and his government.[70]

Aftermath

On 29 July, a group of defected officers announced the formation of the Free Syrian Army (FSA). Composed of defected Syrian Armed Forces personnel, the rebel army seeks to remove Bashar al-Assad and his government from power. On 23 August, the Syrian National Council was formed as a political counterpart to the FSA.

Media coverage

Reporting on this conflict was difficult and dangerous from the start: journalists were being attacked, detained, reportedly tortured and killed. Technical facilities (internet, telephone etc.) were being sabotaged by the Syrian government. Both sides in this conflict tried to disqualify their opponent by framing or referring to them with negative labels and terms, or by presenting false evidence.

References

- Oliver, Christin (26 October 2010). "Corruption Index 2010: The Most Corrupt Countries in the World – Global Development". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Zafar, Saad (24 March 2011). "The Assad Poison". AllVoices. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- Mroue, Bassem (18 June 2011). "Bashar Assad Resignation Called For By Syria Sit-In Activists". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Oweis, Khaled; al-Khalidi, Suleiman (8 April 2011). "Pro-democracy protests sweep Syria, 22 killed". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Colvin, Mark (25 March 2011). "Syrian protestors want a regime change". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- McShane, Larry (25 March 2011). "Violence erupts in Syria, Jordan; anti-government protestors shot, stoned". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "Syria to lift decades-old emergency law". Al Jazeera. 19 April 2011. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Oweis, Khaled (29 April 2011). "Muslim Brotherhood endorses Syria protests". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Cooper (2015), p. 21.

- Story, AP. "Syrian troops detain dozens, 3 killed in north". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "As Syria flares, some U.N.'ers take flight". CNN. 18 August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Syria army kills at least 27 in overnight attacks on three main cities". Haaretz. 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- "Syria: 24 Civilians Killed In Tank Attack". Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Syria: 'four dead' in rare demonstrations". The Telegraph. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- "Syrian general: Hundreds of soldiers, police killed by armed gangs". CNN. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- "Syria opposition reaches out to army". The Jordan Times. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Almost 3,000 missing in Syria crackdown, NGO says". NOW News. 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Rania Abouzeid (1 August 2011). "Syrian Military Attacks Protesters in Hama". TIME. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

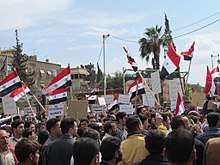

A giant Syrian flag is held by the crowd during a protest against President Bashar Assad in the city center of Hama on July 29, 2011

- Anthony Shadid (30 June 2011). "Coalition of Factions From the Streets Fuels a New Opposition in Syria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Omri, Mohamed-Salah (2012). "A Revolution of Dignity and poetry". Boundary 2. 39 (1): 137–165. doi:10.1215/01903659-1506283.

- Yacoub Oweis, Khaled (22 March 2011). "Fear barrier crumbles in Syrian "kingdom of silence"". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Fountain, Henry (2 March 2015). "Researchers Link Syrian Conflict to a Drought Made Worse by Climate Change". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "'Day of Rage' Protest Urged in Syria". NBC News. 3 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Levinson, Charles; Coker, Margaret; Cairo, Matt Bradley in; Entous, Adam; Washington, Jonathan Weisman in (12 February 2011). "Fall of Mubarak Shakes Middle East". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- al-khouy, Firas (6 October 2011). "Graffiti Wars and Syria's Spray Man". Al Akhbar English. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Mid-East unrest: Syrian protests in Damascus and Aleppo". BBC News. 15 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Fahim, Kareem; Saad, Hwaida (8 February 2013). "A Faceless Teenage Refugee Who Helped Ignite Syria's War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Droz-Vincent, Philippe (Winter 2014). ""State of Barbary" (Take Two): From the Arab Spring to the Return of Violence in Syria". Middle East Journal. Middle East Institute. 68 (1). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Macleod, Hugh (23 April 2011). "Syria: How it all began". Public Radio International. Archived from the original on 16 December 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Sinjab, Lina (19 March 2011). "Middle East unrest: Silence broken in Syria". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Middle East unrest: Silence broken in Syria". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Flamand, Hugh Macleod and Annasofie. "Tortured and killed: Hamza al-Khateeb, age 13". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "President Assad's interview with SBS NEWS AUSTRALIA". Retrieved 22 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- Al Jazeera Arabic قناة الجزيرة (23 March 2011), اقتحام الأمن السوري المسجد العمري في مدينة درعا, archived from the original on 22 March 2016, retrieved 17 February 2016

- "We've Never Seen Such Horror". Human Rights Watch. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "Syria: Seven Police Killed, Buildings Torched in Protests". Israel National News. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Holliday, Joseph (December 2011). "The Struggle for Syria in 2011" (PDF). Institute for the Study of War. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- "Officers Fire on Crowd as Syrian Protests Grow". The New York Times. 20 March 2011. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Iddon, Paul (30 July 2012). "A recap of the Syrian crisis to date". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Slackman, Michael (25 March 2011). "Syrian Troops Open Fire on Protesters in Several Cities". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Arrest of leader of the Islamic Democratic movement in Syria". Elaph (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Jailed prominent Syrian opposition for seven and a half years". Free Syria (in Arabic). 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Syrian authorities detain national identity Adnan Mustafa Abu Ammar". Free Syria (in Arabic). 28 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Police Kill 6 Protesters in Syria". The New York Times. 18 March 2011. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Beyond Arms, Syria Uses Arrests Against Uprising". The New York Times. 27 June 2012. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Syria: Torture Centers Revealed". Human Rights Watch. 3 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "Opposition: 127 dead as Syrian forces target civilians". CNN. 7 April 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Oweis, Khaled (22 April 2011). "Almost 90 dead in Syria's bloodiest day of unrest". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- al-Khalidi, Suleiman (19 March 2011). "Syrian mourners call for revolt, forces fire tear gas". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "President al-Assad Issues Decree on Discharging Governor of Daraa from His Post". Syrian Arab News Agency. 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- "In Syrian flashpoint town, more deaths reported". CNN. 25 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- al-Hatem, Fadwa (31 May 2011). "Syrians are tired of Assad's 'reforms'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Syria lifts niqab ban, shuts casino, in nod to Sunnis". Reuters. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- "Stateless Kurds in Syria granted citizenship". CNN. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Hassan, Nidaa; Borger, Julian (10 July 2011). "Syrian 'national dialogue' conference boycotted by angry opposition". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Syria opens 'national dialogue' with opposition". BBC News. 10 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Oweis, Khaled Yacoub; Karouny, Mariam; al-Khalidi, Suleiman; Aboudi, Sami (21 April 2011). "Syria's Assad ends state of emergency". Beirut, Amman, Cairo. Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- Macfarquhar, Neil; Stack, Liam (1 April 2011). "In Syria, Thousands Protest, Facing Violence, Residents Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Shadid, Anthony (25 April 2011). "Syria Escalates Crackdown as Tanks Go to Restive City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Civilian killings in Syrian demonstrations rises to 800". The Jerusalemn Post. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- "Syrian army tanks 'moving towards Hama'". BBC News. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Abdelaziz, Salma (15 May 2011). "Shallow grave yields several bodies in Syrian city marked by unrest". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- "Syria death toll 'surpasses 1,000'". Al Jazeera. 24 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- "Interactive: Tracking Syria's defections". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Dagher, Sam; Gauthier-Villars, David (6 July 2012). "In Paris, Diplomats Cheer Syria General's Defection". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- "Syrian forces take over northwestern town of Maaret al-Numan". Associated Press. 17 June 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2017 – via Haaretz.

- "Syria unrest: Protests in Aleppo as troops comb border". BBC News. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Syria: 'Hundreds of thousands' join anti-Assad protests". BBC News. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- "In Damascus, Amid Uprising, Syrians Act Like Nothing's Amiss". The New York Times. 5 September 2011. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Syria: What motivates an Assad supporter?". Global Post. 24 June 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

Works cited

- Cooper, Tom (2015). Syrian Conflagration. The Civil War 2011–2013. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-10-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)