Charding Nullah

The Charding Nullah, traditionally known as the Lhari stream and called the Demchok River by China, is a small river that serves as the de facto border between China and India in the Demchok sector of the greater Sino-Indian border dispute.[lower-alpha 1] The river originates near the Charding La pass that is also on the border between the two countries and flows northeast to join the Indus River near a peak called "Lhari Karpo" (white holy peak). There are villages on both sides of the mouth of the river, both named Demchok ("Dêmqog" in Tibetan pinyin transliteration).

| Charding Nullah Lhari stream, Demchok River | |

|---|---|

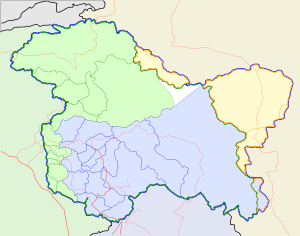

Charding Nullah relative to the Kashmir region | |

Charding Nullah relative to Tibet | |

| Location | |

| country | India, China |

| region | Kashmir, Tibet |

| union territory/province | Ladakh, Tibet Autonomous Region |

| district/prefecture | Leh, Ngari Prefecture |

| subdistrict/county | Nyoma, Gar |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Charding La |

| • coordinates | 32.5573°N 79.3838°E |

| • elevation | 5,170 m (16,960 ft) |

| Mouth | Indus River |

• location | Demchok |

• coordinates | 32°42′N 79°28′E |

• elevation | 4,200 m (13,800 ft)[1][2] |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Indus River |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Nilu Nullah |

| Demchok River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 典角河 | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Diǎnjiǎo hé | ||||||

| |||||||

The river was mentioned by the name "Lhari stream" in a treaty between Ladakh and Tibet in 1684 and stated as the boundary between the two regions. After independence in 1947, India claimed the southern watershed of the river (roughly 3 miles southeast of it) as its boundary, which has been contested by the People's Republic of China, whose border claim lies roughly 10 miles northwest of the river. The two countries fought a brief war in 1962, after which the Demchok region has remained divided between the two nations across a Line of Actual Control.

Etymology

The Indian government refers to the river as "Charding Nullah" after its place of origin, the Charding La pass, with nullah meaning a mountain stream.

The Chinese government uses the term "Demchok river" by the location of its mouth, near the Demchok village.[lower-alpha 1]

The historical documents name the river as "Lhari stream".[4] Lhari,[lower-alpha 2] meaning "holy mountain" in Tibetan, is the name used for the white rocky peak (4,865 m) behind the village of Demchok.[5][6] It has also been referred to as "Lari Karpo" ("white lhari") and "Demchok Lari Karpo" in Tibetan documents.[7][lower-alpha 3] "Lhari stream at Demchok" is the phrase used in the summary of the 1684 Treaty of Tingmosgang from the Ladakh Chronicles,[10] forming the basis for the Indian government's identification of the stream with Charding Nullah.[11][lower-alpha 4]

Description

|

The Charding Nullah originates below the Charding La pass, which is on a large spur that divides the Sutlej river basin from the Indus river basin. In this area, the Sutlej river tributaries flow southeast into West Tibet and the Indus river and its tributaries flow northwest, parallel to the Himalayan ranges.

The Charding Nullah flows northeast along a narrow mountain valley. Halfway down the valley it is joined by another nullah from the left, called Nilu Nullah (or Nilung/Ninglung). The Charding–Nilu Nullah Junction (CNNJ, 4900 m) is recognised by both the Indian and Chinese border troops as a strategic point.[13]

The entire area surrounding the Charding Nullah is referred to as the Changthang plateau. It consists of rocky mountain heights of Ladakh and Kailas ranges and sandy river valleys which are only good for grazing yaks, sheep and goats (the famous pashmina goats) reared by Changpa nomads.[14] The Indian-controlled northern side of the nullah is close to Hanle, the site of the Hanle Monastery. The Chinese-controlled southern side has the village of Tashigang (Zhaxigang) which also has a monastery, both having been built by the Ladakhi ruler Sengge Namgyal (r. 1616–1642).[15] At the end of Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War, the Tibetan troops retreated to Tashigang where they fortified themselves.[16]

|

At the bottom of the valley, the Charding Nullah branches into a 2 km-wide delta as it joins the Indus river.[17] During the British colonial period, there were villages on both the sides of the delta, going by the name "Demchok". The southern village appears to have been the main one, frequently referred to by travelers.[18] The Governor of Ladakh, who visited the border area in 1904–05 mentioned that the southern Tibetan village at Demchok had 8 or 9 huts, while the northern Ladakhi village at Demchok had only two.[19] The current spellings "Demchok" and "Dêmqog" are used for the Ladakhi and Tibetan villages respectively.

Prior to the Sino-Indian War of 1962, India had established a border post to the south of the delta (called the "New Demchok post"). As the war progressed, the post was evacuated and the Chinese forces occupied it.[20][6] Travel writer Romesh Bhattacharji states they expected to set up a trading village, but India never renewed trade after the war. He states that the southern Dêmqog village has only commercial buildings whereas the northern village has many security-related buildings.[21]

Both the Indians and the Chinese have track roads going up the valley on the two sides of the Charding Nullah, reaching up to the CNNJ. Occasional stand-offs between the two forces at CNNJ are reported in the newspapers.[22]

History

Treaty of Tingmosgang (1684)

The Ladakh Chronicles (La-dvags-rgyal-rabs) mention that, at the conclusion of the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War in 1684, Tibet and Ladakh agreed on the Treaty of Tingmosgang, by which the extensive territories in West Tibet (Ngari) previously controlled by Ladakh were removed from its control. Ladakh was reduced to approximately its present extent. The original text of the Treaty of Tingmosgang no longer survives,[23][24] but the summary in the Chronicles of Ladakh recorded that the frontier of Ladakh with Tibet was fixed at the "Lha-ri stream at Demchok".[25] Most sources agree that this border involved cession of territory for Ladakh. Ladakh had earlier annexed the entire West Tibet under its ruler Sengge Namgyal (r. 1624–1642).[26] The reduction of Ladakh was in effect a retaliation by Lhasa. The traditional border between the two regions prior to these conflicts is not clearly known.[lower-alpha 5]

According to Alexander Cunningham, "A large stone was then set up as a permanent boundary between the two countries, the line of demarcation drawn from the village of Dechhog [Demchok] to the hill of Karbonas."[28][29]

Roughly 160 years after the Treaty of Tingmosgang, Ladakh came under the rule of the Dogras, who launched an invasion into the West Tibet leading to the Dogra–Tibetan War. The war ended in a stalemate. The resulting Treaty of Chushul in 1842 bound the parties to the "old, established frontiers".[30]

British boundary commission (1846–1847)

After the Dogras joined the British suzerainty as the state of Jammu and Kashmir, the British government dispatched a boundary commission consisting of P. A. Vans Agnew and Alexander Cunningham to define the borders of the state with Tibet in 1846–1847.[31][lower-alpha 6] The Chinese government was invited to join the effort for a mutually agreed border. However the Chinese declined, stating that the frontier was well-known and it did not need a new definition.[33] The British boundary commission nevertheless surveyed the area. Its report stated:

[Demchok] is a hamlet of half a dozen huts and tents, not permanently inhabited, divided by a rivulet (entering the left bank of the Indus) which constitutes the boundary of this quarter between Gnari ... [in Tibet] ... and Ladakh.[34]

The "rivulet" is evidently the Charding nullah. The Tibetan frontier guards prohibited the commission from proceeding beyond the rivulet.[34]

The commission placed the border on Indus at Demchok, and followed the mountain watershed of the Indus river on its east, passing through the Jara La and Chang La passes.[35] This appears to be the first time that the watershed principle was used in the Indian subcontinent for defining a boundary. Scholar Alastair Lamb remarks that it was probably unknown to the Asian inhabitants of the region, but something like it was necessary for connecting the known landmarks to create a boundary line.[36][lower-alpha 7]

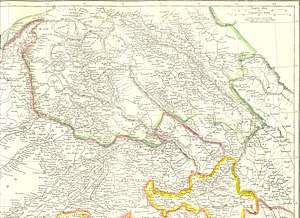

Survey of Kashmir, Ladak, and Baltistan or Little Tibet (1847–1868)

Between 1847 and November 1864, the British Indian government conducted the Survey of Kashmir, Ladak, and Baltistan or Little Tibet, which was reproduced in a reduced form in the Kashmir Atlas of 1868 by the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India.[37][38][39] Even though this was not an official boundary commission, the survey made several adjustments to the boundary, including in the Demchok sector. Lamb states:

Where Strachey had put the boundary actually at Demchok, the Kashmir Atlas (Sheet 17) put it about sixteen miles downstream on the Indus from Demchok, thus coming nearer to the [present] Chinese than the Indian claim line.[40]

Lamb interprets this as a "compromise". According to him, the British gave up territory in Demchok to include other territory near the Spanggur Lake.[41][lower-alpha 8]

In reality, the British knowledge of Ladakh was quite limited at this early stage. Maharaja Gulab Singh was zealous of his independence and the British distrusted his "expansionist" tendencies. Indian commentators state that the revenue records from the period of the survey show that the Demchok area was administered by Ladakh. This information did not apparently filter down to the survey team.[43][44]

Late colonial era (1868–1947)

Subsequent to the Kashmir Atlas of 1868, the British gained much knowledge of Ladakh. Frederic Drew entered the service of Kashmir as a geologist in 1862, publishing his seminal work Jammoo and Kashmir Territories in 1875. The text of the Ladakh Chronicles, only known to Europeans since 1847, was published by Moravian missionary Karl Marx in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal between 1891 and 1902.[45][46] However, no revisions were made to the border at Demchok in the light of the new discoveries. Some maps from world powers including China came to adopt the borders depicted in the Kashmir Atlas during the two World Wars.[47]

According to Lamb, the majority of British maps published between 1918 and 1947 showed Demchok as being in Tibet and that "in the Demchak region the British line followed a course very close to that of the present Chinese claim".[48]:39

On the ground, the traditional boundaries continued to be followed. The Kashmir government disregarded the British maps and the Tibetan claims to Demchok seem to have persisted.[lower-alpha 9] Lamb states, "by the time of the Transfer of Power in 1947 nothing had been settled."[50]

Modern claims (1947–present)

Since the 1950s, Indian maps do not agree entirely with either the 1846–1847 survey or the 1868 Kashmir Atlas: the Indian claims lie 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Demchok, whereas the 1846–1847 British boundary commission placed the border between the two Demchok villages, and British maps from the 1860s onwards showed the border to be 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Demchok.[48]:48 The Chinese claims are close to the later British maps.[48]:39,48 The Chinese claims also coincided with the borders used by the 1945 National Geographic and 1955 United States Army Map Service maps.[27]:152

Sources vary on whether the Demchok sector is administered by China or India.[51]

See also

Notes

- On 21 September 1965, the Indian Government wrote to the Chinese Government, complaining of Chinese troops who were said to have "moved forward in strength right up to the Charding Nullah and have assumed a threatening posture at the Indian civilian post on the western [northwestern] side of the Nullah on the Indian side of the 'line of actual control'." The Chinese Government responded on 24 September stating, "In fact, it was Indian troops who on September 18, intruded into the vicinity of the Demchok village on the Chinese side of the 'line of actual control' after crossing the Demchok River from Parigas (in Tibet, China)..."[3]

- Alternative spellings of Lahri include "Lahri", "Lari" or "Lairi"

- Scholars translate the Tibetan term lha-ri as "soul mountain". Many peaks in Tibet are named lhari including a "Demchok lhari" in the northern suburbs of Lhasa.[8][9] "Karpo", meaning "white", serves to distinguish the Ladakh's mountain peak from the others.

- Fisher et al. states that the Lhari stream flows "five miles southeast of Demchok".[12] This seems incorrect. Rather the Indian alignment of the border is five miles southeast of Demchok. It follows the watershed of the Lhari stream/Charding Nullah. See Indian Report, Part 1 (1962), Q21 (p. 38)

- A. H. Francke, who first studied the history of West Tibet believed that, when the West Tibetan kingdom of Kyide Nyimagon was divided among his three sons c. 930, the borders of Ladakh (then called Maryul) stretched up to the Sengge Zangbo river valley. This is echoed by Wim van Eekelen, who has stated that the treaty border was "based on a partition effected in the 10th century".[27]:8 This is contested by other historians. It is unlikely that the borders remained unchanged up to the 17th century.

- Agnew and Cunningham were assisted by Henry Strachey, who later became a notable explorer in his own right. Agnew and Cunningham were told to "bear in mind that, it is not a strip more or less of barren or even productive territory that we want, but a clear and well defined boundary in a quarter likely to come little under observation".[32]

- Cunningham remarked: "In laying down a boundary through mountainous country it appeared to the Commissioners desirable to select such a plan as would completely preclude any possibility of further dispute. This the Commissioners believe they have found in their adoption as a boundary of such mountain ranges as form water-shed lines between the drainages of different rivers."[36]

- The idea of "compromise" seems to contradict other observation of Lamb regarding the virtues of the survey, e.g., "Henry Strachey, and the Kashmir surveyors, like Godwin Austen, made careful inquiries as to the whereabouts of the traditional boundary". (emphasis added.)[42]

- Claude Arpi narrates the description of a murder inquiry in 1939, conducted by the British Trade Agent in Gartok and the governor of Ladakh (wazir-e-wazarat) jointly with the Tibetan officials (garpons). The Indian officials travelled from Leh to Demchok for this purpose, where they camped at the Lhari stream, described as "a natural boundary between Tibet and Kashmir at Demchok".[49]

References

- Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Ch. 9.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), pp. 374–375.

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1966), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: January 1965 - February 1966, White Paper No. XII (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs – via claudearpi.net

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 107.

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 160; Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Chapter 9: "Changthang: The High Plateau"

- Claude Arpi, The Case of Demchok, Indian Defence Review, 19 May 2017.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 106–107.

- McKay, Alex (2015), Kailas Histories: Renunciate Traditions and the Construction of Himalayan Sacred Geography, BRILL, p. 520, ISBN 978-90-04-30618-9

- Khardo Hermitage (Khardo Ritrö), Mandala web site, University of Virginia, retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 38.

- Indian Report, Part 2 (1962), pp. 47–48: "There was only one Lhari in the area, and that was the stream joining the Indus near Demchok at Longitude 79° 28' E and Latitude 32° 42' N."

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 39.

- Chinese troops cross LAC in Ladakh again, India Today, 16 July 2014.

- Ahmed, Monisha (2004), "The Politics of Pashmina: The Changpas of Eastern Ladakh", Nomadic Peoples – New Series, White Horse Press, 8 (2): 89–106, doi:10.3167/082279404780446041, JSTOR 43123726

-

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 143: "Magnificent monasteries were built at Hemis, Theg-mchog (Chemrey), Anle [Hanle] and Tashigong [Tashigang]."

- Jina, Prem Singh (1996), Ladakh: The Land and the People, Indus Publishing, p. 88, ISBN 978-81-7387-057-6: "He [Sengge Namgyal] built many monasteries such as Hemis, Chemde, Wanla [Hanle] and Tashigang. He also built the castle of Leh palace."

- Shakspo, Nawang Tsering (1999), "The Foremost Teachers of the Kings of Ladakh", in Martijn van Beek; Kristoffer Brix Bertelsen; Poul Pedersen (eds.), Recent Research on Ladakh 8, Aarhus University Press, p. 286, ISBN 978-87-7288-791-3: "They founded the renowned Hemis Gonpa, Chemre Gonpa and Wanla Gonpa [Hanle]. Sengge Namgyal also had a monastery built at Tashigang in western Tibet."

-

- Emmer, the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (2007), p. 98

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 156

- Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area (2017): According to Hedin, "Right in front of us the monastery Tashi-gang gradually grows larger. Its walls are erected on the top of an isolated rock of solid porphyrite, which crops up from the bottom of the Indus valley like an island drawn out from north to south. (…) on the short side stand two round free-standing towers, (…). The whole is surrounded by a moat 10 feet deep (…)".

- Claude Arpi, Demchok and the New Silk Road: China's double standard, Indian Defence Review, 4 April 2015. "View of the nalla" image.

- Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area (2017), p. 353: 'At present officially located in India, the village of Demchok marked the border between Tibet and Ladakh for a long time. Abdul Wahid Radhu, a former representative of the Lopchak caravan, described Demchok in his travel account as "the first location on the Tibetan side of the border".'

- Indian Report, Part 3 (1962), pp. 3–4: According to a report by the governor of Ladakh in 1904–05, "I visited Demchok on the boundary with Lhasa. ... A nullah falls into the Indus river from the south-west and it (Demchok) is situated at the junction of the river. Across is the boundary of Lhasa, where there are 8 to 9 huts of the Lhasa zamindars. On this side there are only two zamindars."

- Cheema, Crimson Chinar (2015), p. 190.

- Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Chapter 9: "Changthang: The High Plateau".

- India, China admit to intrusion by Chinese herdsmen, Gulf News, 28 July 2014.

- Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector 1965, pp. 37, 38, 40:

- "No text of this agreement between Tibet and Ladakh survives, but there are references to it in chronicles"

- "There can be no doubt that the 1684 (or 1683) agreement between Ladakh and the authorities then controlling Tibet did in fact take place. Unfortunately, no original text of it has survived and its terms can only be deduced. In its surviving form there seems to be a reference to a boundary point at 'the Lhari stream at Demchok', a stream which would appear to flow into the Indus at Demchok and divide that village into two halves."

- "The treaty that could have given this information, that of 1684, has not survived in the form of its full text, and we have no means of determining exactly what line of frontier was contemplated in 1684. The chronicles which refer to this treaty are singularly deficient in precise geographical details."

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 1,3: "The main source for Ladakhi history is, and always will be, the La-dvags rgyal-rabs, compiled probably in the 17th century, but continued later till the end of the kingdom and beyond. [...] The only other literary source from Ladakh is the biography of sTag-ts'ah-ras-pa (TTRP), compiled in 1663."

-

- Francke, Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part (Volume) II (1926, pp. 115–116): "Regarding Mnah-ris-skor-gsum Mi-pham-dban-po's stipulations were to this effect :— [...] With this exception the boundary shall be fixed at the Lha-ri stream at Bde-mchog."

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963): "... the border between Ladakh and Tibet was fixed at the Lha-ri stream, which flows into the Indus five miles southeast of Demchok."

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977, p. 78): "With this exception [of Men-ser], the frontier was fixed at the Lha-ri stream near bDe-mc'og."

- Ahmad, New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (1968, p. 351): "Now, in 1684, the government of Tibet, headed by the sDe-pa Sans-rGyas rGya-mTsho, annexed Gu-ge to Tibet, and fixed the frontier between Ladakh and Tibet at the lHa-ri stream at bDe-mChog."

- Bray, The Lapchak Mission (1990, p. 77): "The boundary between Ladakh and Tibet was to be established at the Lha-ri stream in Demchog..."

- Emmer, the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (2007, pp. 99–100): "The frontier with Tibet was fixed at the Lha ri stream at Bde mchog (Demchok), approximately at that places where it is even today."

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001, p. 160): "The hill of Lahri [Lhari] that stands near Demchok was fixed as the boundary between Lhasa and Ladakh."

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 90.

- van Eekelen, Willem Frederik (1964). Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China. Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-0715-8. ISBN 978-94-015-0715-8.

- Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969), pp. 42–43.

- Cunningham, Ladak (1854), p. 328.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 55–56.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 64.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 66.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), pp. 64–66.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 68.

- Maxwell, India's China War 970, map opposite p. 40.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 67.

- Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 47The first good set of maps of Kashmir, though still very defective in the Aksai region, were Photozincographed Sections of part of, the Survey of Kashmir, Ladak, and Baltistan or Little Tibet, 20 sheets, 8 miles to the inch, published by the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, Dehra Dun, October 1868.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 43: "The Kashmir Survey which officially completed its task in November 1864 [Footnote:] Strachey's map, in two sheets at 8 miles to the inch, can be seen in the Map Rooms of the Royal Geographical Society and the India Office Library. It has been reproduced, much reduced, in Atlas, maps 11 & 12. [...] The results of the Kashmir Survey were published as an Atlas in 1868, and they give a good indication of the Ladakh-Tibet boundary over some of its length. [Footnote:] Photozincographed Sections of part of the Survey of Kashmir, Ladak and Baltistan or Little Tibet, Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, Dehra Dun, Oct. 1868; 20 sheets at a scale of 16 miles to the inch (1.0. Map Room, cat. no. F/IV/r6")

- Karackattu, Joe Thomas (2018). "India–China Border Dispute: Boundary-Making and Shaping of Material Realities from the Mid-Nineteenth to Mid-Twentieth Century". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 28 (1): 135–159. doi:10.1017/S1356186317000281. ISSN 1356-1863.

One of the earliest official delimitations of the northern frontiers of India appears in photozincographed sections of part of the survey of Kashmir, Ladak and Baltistan or Little Tibet showing the “Boundary of His Highness the Maharajah of Kashmir” (8 miles to 1 inch, Dehradoon, October 1868).

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), pp. 72–73.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 173.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 42.

- Rao, The India-China Border (1968):

- p.24: "But such an evaluation was seldom done and although most officials traced the boundary correctly along the watershed range running parallel to the river Indus, gross blunders were committed regarding the alignment in the Pangong and Demchok areas. This was apparently due to the unfamiliarity of some of the British officials with the traditional and treaty basis of the boundary and to their mistaking local disputes such as pasture disputes with boundary disputes."

- p.29: "The Kashmir Atlas boundary conflicts also with the first-hand evidence provided by the 1847 Commission. In regard to Demchok, it conflicts with well-established facts of history and with revenue records for the very period that the survey was conducted."

- Bray, The Lapchak Mission (1990), p. 75: "Many of these relationships had their origin in the distant past, and the British at first understood their full significance imperfectly, or not at all."

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 1.

- Bray, The Lapchak Mission (1990), p. 77.

- See Atlas of the Northern Frontier of India, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, Maps 3 and, 6.

- Lamb, Alastair (1965). "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF). The Australian Year Book of International Law. 1 (1): 37–52.

- Claude Arpi, The curious case of Demchok, The Pioneer, 16 August 2018.

- Lamb, Tibet, China & India (1989), p. 360.

- The following sources state that the Demchok sector is administered by China:The following sources state that the Demchok sector is administered by India:

- "Jammu & Kashmir". European Foundation for South Asian Studies. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Snow, Shawn (19 September 2016). "Analysis: Why Kashmir Matters". The Diplomat. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Ruiz Estrada, Mario Arturo; Koutronas, Evangelos; Khan, Alam; Angathevar, Baskaran (2018). "Economic Dynamics of Territorial Military Conflicts: The Case of Kashmir". Journal of Strategic Studies. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3102745. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Tamkin, Emily; Karklis, Laris; Meko, Tim (28 February 2019). "The Trouble with Kashmir". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

Bibliography

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890

- India, Ministry of External Affairs (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (September–December 1968), "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", East and West, Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO), 18 (3/4): 340–361, JSTOR 29755343

- Bhattacharji, Romesh (2012), Ladakh: Changing, Yet Unchanged, New Delhi: Rupa Publications – via Academia.edu

- Bray, John (Winter 1990), "The Lapchak Mission From Ladakh to Lhasa in British Indian Foreign Policy", The Tibet Journal, 15 (4): 75–96, JSTOR 43300375

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, pp. 51–, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854), Ladak: Physical, Statistical, Historical, London: Wm. H. Allen and Co – via archive.org

- Emmer, Gerhard (2007), "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, BRILL, pp. 81–108, ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via Questia

- Handa, O. C. (2001), Buddhist Western Himalaya: A Politico-Religious History, Indus Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-7387-124-5

- Francke, August Hermann (1926), Thomas, F. W. (ed.), Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part (Volume) II

- Howard, Neil; Howard, Kath (2014), "Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley, Eastern Ladakh, and a Consideration of Their Relationship to the History of Ladakh and Maryul", in Lo Bue, Erberto; Bray, John (eds.), Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, pp. 68–99, ISBN 9789004271807

- Lamb, Alastair (1964), The China-India border, Oxford University Press

- Lamb, Alastair (1965), "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF), The Australian Year Book of International Law: 37–52

- Lamb, Alastair (1989), Tibet, China & India, 1914-1950: a history of imperial diplomacy, Roxford Books

- Lange, Diana (2017), "Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area between Western Tibet, Ladakh, and Spiti", Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines,The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1

- Petech, Luciano (1977), The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D. (PDF), Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente – via academia.edu

- Rao, Gondker Narayana (1968), The India-China Border: A Reappraisal, Asia Publishing House

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969), Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger – via archive.org

External links

- Demchok Eastern Sector on OpenStreetMap (Chinese-controlled)

- Demchok Western Sector on OpenStreetMap (Indian-controlled)