Caning in Singapore

Caning is a widely used form of corporal punishment in Singapore. It can be divided into several contexts: judicial, prison, reformatory, military, school, and domestic. These practices of caning are largely a legacy of, and are influenced by, British colonial rule in Singapore.[1] Similar forms of corporal punishment are also used in some other former British colonies, including two of Singapore's neighbouring countries, Malaysia and Brunei.

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

Of these, judicial caning is the most severe. It is reserved for male convicts under the age of 50, for a wide range of offences under the Criminal Procedure Code, and is also used as a disciplinary measure in prisons. Caning is also a legal form of punishment for delinquent servicemen in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) and is conducted in the SAF Detention Barracks. Caning is also used as an official punishment in reform schools.

In a milder form, caning is used to punish male students in primary and secondary schools for serious misbehaviour. The government encourages this but does not allow caning for female students, who instead receive alternative forms of punishment such as detention or suspension.

A smaller cane or other implement is also used by some parents to punish their children. This is allowed in Singapore but not encouraged by the government.

The Singapore government has mentioned that it considers "the judicious application of corporal punishment in the best interest of the child."[2]

Judicial caning

History

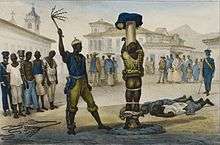

Caning, as a form of legally sanctioned corporal punishment for convicted criminals, was first introduced to Malaya and Singapore by the British Empire in the 19th century. It was formally codified under the Straits Settlements Penal Code Ordinance IV in 1871.[1]

In that era, offences punishable by caning were similar to those punishable by birching or flogging in England and Wales. They included robbery, aggravated forms of theft, burglary, assault with the intention of sexual abuse, a second or subsequent conviction of rape, a second or subsequent offence relating to prostitution, and living on or trading in prostitution.[1]

Caning remained on the statute book after Malaya declared independence from Britain in 1957, and after Singapore ceased to be part of Malaysia in 1965. Subsequent legislation has been passed by the Parliament of Singapore over the years to increase the minimum strokes an offender receives, and the number of crimes that may be punished with caning.[1]

Legal basis

Sections 325–332 of the Criminal Procedure Code lay down the procedures governing caning. They include the following:

- A male offender between the ages of 18 and 50 who has been certified to be in a fit state of health by a medical officer is liable to be caned.[3]

- The offender shall receive no more than 24 strokes of the cane on any one occasion, irrespective of the total number of offences committed.[4] In other words, a man cannot be sentenced to more than 24 strokes of the cane in a single trial, but he may receive more than 24 strokes if the sentences are given out in separate trials.[5]

- If the offender is under 18, he may receive up to 10 strokes of the cane,[4][6] but a lighter cane will be used in this case.[7] Boys under 16 may be sentenced to caning only by the High Court and not by the State Courts.

- An offender sentenced to death shall not be caned.

- The rattan cane used shall not exceed 1.27 cm (0.50 inches) in diameter.[7]

- Caning must not be carried out in instalments.[6] This is to ensure that prisoners sentenced to caning are done with it in a single session and do not have to go through the process repeatedly even if the full sentence might not have been administered for medical reasons.[8]

Any male convict, whether sentenced to caning or not, may also be caned in prison if he commits certain offences while serving time in prison.[9]

Exemptions

The following groups of people are not allowed to be caned:[10]

- Women

- Men above the age of 50

- Men sentenced to death whose sentences have not been commuted

It was not uncommon for the courts to extend, by up to 12 months,[11] the prison terms of offenders originally sentenced to caning but later found to be medically unfit to undergo the punishment. However, on 9 May 2017, the High Court ruled that the courts should not automatically impose an additional jail term in lieu of caning unless there are reasons to do so.[12]

Offences punishable by caning

Singaporean law allows caning to be ordered for over 35 offences, including hostage-taking/kidnapping, robbery, gang robbery with murder, rioting, causing grievous hurt, drug abuse, vandalism, extortion, sexual abuse, molestation[13] (often referred to as "outrage of modesty"), and unlawful possession of weapons. Caning is also a mandatory punishment for certain offences such as rape, drug trafficking, illegal moneylending,[14] and for foreigners who overstay by more than 90 days – a measure designed to deter illegal immigrants.[15]

While most of Singapore's laws on offences punishable by caning were inherited from the British legal system through the Indian Penal Code, the Vandalism Act was only introduced in 1966 after independence, in what has been argued[16] to be an attempt by the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) to suppress the opposition's activities in the 1960s because opposition supporters vandalised public property with anti-PAP graffiti. Vandalism was originally prohibited by the Minor Offences Act, which made it punishable by a fine of up to S$50 or a week in jail, but did not permit caning.[16] As of today, the Vandalism Act imposes a mandatory caning sentence of between three to eight strokes for a conviction of vandalism. Caning is not imposed on first-time offenders who use delible substances (e.g. pencil, crayon, chalk) to commit vandalism.[17]

Beginning in the 1990s, the higher courts have been more inclined to impose caning sentences in cases where caning is a discretionary punishment. For example, in 1993 an 18-year-old molester was initially sentenced to six months' imprisonment but he appealed against his sentence. Chief Justice Yong Pung How not only dismissed his appeal, but also added three strokes of the cane to the sentence. This precedent set by the Chief Justice became a benchmark for sentences in molest cases, where the court is expected to sentence a molester to at least nine months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane if the offence involves touching the victim's private parts.[18]

In some cases, male employees can be sentenced to caning for offences committed by the company they work for. For instance, the Dangerous Fireworks Act states that caning is mandatory for a manager or owner of a company which imports, delivers or sells dangerous fireworks. Another example is the transporting of illegal immigrants; a manager of a company who authorises or participates in such activity can be sentenced to caning.[18] In July 1998, police reported six cases of employers sentenced to imprisonment and caning for hiring illegal immigrants.[19]

Contrary to what has sometimes been misreported, the importation of chewing gum is subject only to fines; it is not and has never been an offence punishable by caning.[20]

Statistics

In 1993, the number of caning sentences ordered by the courts was 3,244.[21]

By 2007, this figure had doubled to 6,404, of which about 95% were actually implemented.[22] Since 2007, the number of caning sentences has experienced an overall decline, falling to just 1,257 in 2016.

Caning takes place at several institutions around Singapore, most notably Changi Prison, and including the now defunct Queenstown Remand Centre, where Michael Fay was caned in 1994. Canings are also administered in Drug Rehabilitation Centres.

| Year | Number of sentences | Sentences carried out | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 3,244 | [21] | |

| 2006 | 5,984 | 95% | [23] |

| 2007 | 6,406 | 95% | [22] |

| 2008 | 4,078 | 98.7% | January to September only[24] |

| 2009 | 4,228 | 99.8% | January to November only[25] |

| 2010 | 3,170 | 98.7% | [26] |

| 2011 | 2,318 | 98.9% | [27] |

| 2012 | 2,500 | 88.1% | [28] |

| 2014 | 1,430 | 86% | January to September only[29] |

| 2015 | 1,382 | 81.7% | January to October only[30] |

| 2016 | 1,257 | 78.5% | January to October only[31] |

Most caning sentences are far below the legal limit of 24 strokes. Although sentences of between three and six strokes are much more common, they usually receive less or no coverage by the media. Normally, only the more serious cases involving heavier sentences will have a greater tendency to be reported in the press.[32]

Caning officers

The prison officers who administer caning are carefully selected and specially trained for the job. They are generally physically fit and robustly built. Some hold "quite high" grades in martial arts even though proficiency in martial arts is not a requirement for the job.[33] They are trained to use their entire body weight as the power behind every stroke instead of using only the strength from their arms,[34] as well as to induce as much pain as possible. They can swing the cane at a speed of up to 160 km/h (99 miles per hour)[35] and produce a force upon impact of at least 90 kg (200 pounds).[36]

The Cane

A rattan[37] cane no more than 1.27 cm (0.5 inches) in diameter[7] and about 1.2 m (3.9 feet) in length is used for judicial and prison canings. It is about twice as thick as the canes used in the school and military contexts. The cane is soaked in water overnight to make it supple and prevent it from splitting and embedding splinters in the wounds.[34] The Prisons Department denies that the cane is soaked in brine, but has said that it is treated with antiseptic before use to prevent infection.[38] A lighter cane is used for juvenile offenders.[7]

Administration procedure

Caning is, in practice, always ordered in addition to a jail sentence and never as a punishment by itself. It is administered in an enclosed area in the prison out of the view of the public and other inmates.[8] However, anecdotal evidence suggests that the offender, while waiting in a queue for his turn to be caned, has the chance to observe those before him getting caned.[39] The order is determined by the number of strokes the offender is receiving, with the largest number going first.[40] A medical officer and the Superintendent of Prisons are required to be present at every caning session.[41]

The offender is not told in advance when he will be caned; he is notified only on the day his sentence is to be carried out.[42] Offenders often undergo a lot of psychological distress as a result of being put into such uncertainty.[35] On the day itself, the medical officer examines him by measuring his blood pressure and other physical conditions to check whether he is medically fit for the caning. If he is certified fit, he proceeds to receive his punishment; if he is certified unfit, he is sent back to the court for the sentence to be remitted or converted to additional time in prison. A prison officer confirms with him the number of strokes he has been sentenced to.[43]

In practice, the offender is required to strip completely naked for the caning. Once he has removed his clothes, he is restrained in a large wooden trestle based on the British dual-purpose prison flogging frame. He stands barefooted on the trestle base and bends over a padded horizontal crossbar on one side of the trestle, with the crossbar adjusted to around his waist level. His feet are tied to a lower crossbar on the same side by restraining ankle cuffs made of leather, while his hands are secured to another horizontal crossbar on the other side by wrist cuffs of similar design; his hands can hold on to the crossbar. After he is secured to the trestle in a bent-over position at an angle of close to 90° at the hip, protective padding is tied around his lower back to protect the vulnerable kidney and lower spine area from any strokes that might land off-target.[38][44] The punishment is administered on his bare buttocks[45] to minimise the risk of any injury to bones and organs.[8] He is not gagged.[38]

The caning officer carefully positions himself beside the trestle and takes aim with the cane. The Director of Prisons explained in a 1974 press conference, "Correct positioning is critically important. If he is too near the prisoner, the tip of the cane will fall beyond the buttocks and the force of the stroke will cause the unsupported tip to dip and bend the cane and thus reduce the effect of the stroke. If he is too far, the stroke will only cover part of the buttocks." Strokes are delivered at intervals of about 30 seconds.[34] The caning officer is required to exert as much strength as he can muster for each stroke.[38] The offender receives all the strokes in a single caning session – not in instalments.[6] According to anecdotal evidence, if the sentence involves a large number of strokes (say, six or more), two or more officers will take turns to cane the offender to ensure that the later strokes are equally as forceful as the earlier ones.[46]

During the caning, if the medical officer certifies that the offender is not in a fit state of health to undergo the rest of the punishment, the caning must be stopped.[3] The offender will then be sent back to the court for the remaining number of strokes to be remitted or converted to a prison term of no more than 12 months, in addition to the original prison term he was sentenced to.[47]

Effects

Caning can cause significant physical damage, depending largely on the number of strokes inflicted. Michael Fay, who received four strokes, said in an interview, "The skin did rip open, there was some blood. I mean, let's not exaggerate, and let's not say a few drops or that the blood was gushing out. It was in between the two. It's like a bloody nose."[48]

A report by the Singapore Bar Association stated, "The blows are applied with the full force of the jailer's arm. When the rattan hits the bare buttocks, the skin disintegrates, leaving a white line and then a flow of blood."[49]

Usually, the buttocks will be covered with blood after three strokes.[34] More profuse bleeding may occur in the case of a larger number of strokes. An eyewitness described that after 24 strokes, the buttocks will be a "bloody mess".[40]

Men who were caned have variously described the pain they experienced as "unbearable", "excruciating", "equivalent to getting hit by a lorry",[39] "having a hot iron placed on your buttocks",[40] etc. A recipient of 10 strokes said, "The pain was beyond description. If there is a word stronger than excruciating, that should be the word to describe it".[50][51]

Most offenders struggle violently after each of the first three strokes and then their struggles lessen as they become weaker. By the time the caning is over, those who receive more than three strokes will be in a state of shock. During the caning, some offenders will pretend to faint but they have not been able to fool the medical officer, who decides whether the punishment continues or stops.[52] Offenders often undergo a lot of psychological distress before and during the caning: They are not only afraid of the physical pain, but are also worried whether they can prevent themselves from crying out because crying means that they would "lose face"[34] and be labelled 'weak' by their fellow inmates.[40]

Gopal Baratham, a Singaporean neurosurgeon and opponent of the practice, in his book The Caning of Michael Fay: The Inside Story by a Singaporean, criticised the American tabloid press for false claims, such as that canings are public events (in fact they always take place privately inside the prison):

Two lashers took turns to wield the bamboo cane. Blood spurted, bits of flesh flew and the prisoner screamed in pain. ... The canings drew hundreds of people, including a lot of women, and everybody seemed to love it. Each time the guy got wacked [sic] the crowd would roar – like at a hockey game. They really enjoyed what they saw. (New York Newsday, 20 April 1994)[53]

Recovery

After the caning, the offender is released from the trestle and receives medical treatment. Antiseptic lotion (gentian violet) is applied.[54] The wounds usually take between a week and a month to heal, depending on the number of strokes received. During this time, offenders cannot sit down or lie down on their backs, and experience difficulties when using the toilet. Permanent scars remain even after the wounds have healed.[55]

Notable cases

Foreigners

- Selwyn Hirini Kahukura, Hugh Gordon Clark and Tony Alfred Gordon, three New Zealand soldiers sentenced in 1981 to three years' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane each for selling cannabis in their camp at Dieppe Barracks, Sembawang. They appealed to Singapore's President Devan Nair for clemency in 1982 but the appeals were rejected.[56]

- Michael Fay, an American teenager convicted of vandalism in March 1994 and sentenced to four months' imprisonment, a S$3,500 fine, and six strokes of the cane. This incident attracted worldwide publicity and sparked a minor diplomatic crisis between Singapore and the United States. Under pressure from U.S. President Bill Clinton, Singapore's President Ong Teng Cheong reduced Fay's sentence from six to four strokes. Fay was caned on 5 May 1994 in Queenstown Remand Prison.

- Andy Shiu Chi Ho, a Hong Kong teenager convicted of vandalism along with Michael Fay in March 1994. He was originally sentenced to eight months' imprisonment and 12 strokes of the cane, but his sentence was eventually reduced to six months' imprisonment and six strokes. He received the caning on 23 June 1994.[57]

- David William Peden, a New Zealand former soldier sentenced in November 1997 to one year's imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for overstaying and drug consumption. He was caned on 12 December that year and appeared to be "fine and in good spirits" when a New Zealand consular officer visited him a day after.[58][59]

- Oliver Fricker, a Swiss national who was sentenced on 25 June 2010 to five months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for breaking into the SMRT Trains Changi Depot and vandalising an MRT train by spraypainting it.[60]

- Two Taiwanese nationals, Su Wei Ying and Wu Wei Chun, were sentenced in September 2010 to 21 and 24 months' imprisonment, respectively, and both received 15 strokes of the cane each for loansharking offences. Another Taiwanese national, Chen Ci Fan, was sentenced in January 2011 to 46 months' imprisonment and six strokes of the cane, also in connection with loansharking.[61]

- Samiyappan Sellathurai, an Indian national sentenced to 25 months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane in November 2014 for instigating and participating in the 2013 Little India riot. Over 20 men of South Asian origin were convicted for their respective roles in the riot. Among them, two others also received caning sentences: Arumugam Karthik was sentenced to 33 months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for flipping over three police cars and setting another on fire; Ramalingam Sakthivel was sentenced to 30 months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for flipping over a police car, hitting an ambulance with a pole, and hurling projectiles at police.[62]

- Two Germans, Andreas Von Knorre and Elton Hinz, were each sentenced on 5 March 2015 to nine months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for breaking into a train depot in November 2014 and vandalising a train cabin by spraypainting it.[63]

- Yong Vui Kong, a Malaysian who was caught trafficking heroin in 2007. He was spared the death penalty and re-sentenced to life imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane in 2013 after changes were made to Singapore's laws on drug trafficking. (See Yong Vui Kong v Public Prosecutor for the background of the case). Yong, acting through his lawyer M Ravi, made an appeal to the Court of Appeal against his caning sentence. Ravi argued that the corporal punishment violated the Constitution and that it was racist and discriminatory.[64] In 2015, three judges, including Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, ruled that caning was not unconstitutional and dismissed Yong's appeal.[8][65]

- Bander Yahya A. Alzahrani, a Saudi Arabian diplomat convicted of molesting a hotel intern in 2016. On 3 February 2017, he was sentenced to 26 months and one week in jail and four strokes of the cane. He appealed against his sentence and was released on bail of S$20,000.[66] On 21 July 2017, the High Court dismissed his appeal, Judge of Appeal Steven Chong remarking that his sentence was "actually lenient" especially given the "dishonest" manner in which he ran his defence.[67]

- Khong Tam Thanh, Vu Thai Son and Michael Le, three Britons of Vietnamese descent accused of raping a Malaysian woman in a hotel in Singapore. They pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of aggravated molestation, and were sentenced on 15 August 2017 as follows: Thanh received six years' jail and eight strokes of the cane; Son received 6½ years' jail and eight strokes of the cane; Le received 5½ years' jail and five strokes of the cane.[68]

- Wade James Burridge, an Australian managing director of a horse-racing company convicted of molesting two women in 2015. He was sentenced on 6 December 2017 to 11 months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane. He has appealed against his sentence and is currently out on bail of S$40,000.[69]

- Ye Ming Yuen, a British former DJ convicted of drug trafficking in January 2018 and sentenced to 20 years imprisonment and 24 strokes of the cane. His case made headlines in the United Kingdom after the Daily Mail published an interview with him conducted without authorisation by the Singapore Prison Service. British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt raised the issue and expressed the United Kingdom's opposition to all forms of corporal punishment during his January 2019 visit to Singapore.[70]

Singaporeans

- Qwek Kee Chong, a Singaporean convicted of four counts of armed robbery in 1987 and sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment and 48 strokes of the cane in total (12 strokes for each count). He received all 48 strokes on 8 April 1988 and was hospitalised in the Changi Prison hospital. On 1 March 1991, he sued the government for damages and costs for "grievous injuries to (his) buttocks". This case was believed to be the first time a prisoner was caned beyond the legal limit of 24 strokes.[71] As it was clearly a mistake for him to receive more than 24 strokes in a single session, the government gave him an ex gratia compensation payment in settlement. Other members of Qwek's criminal gang made similar claims in 2007, saying that they also received more than 24 strokes each and did not know at the time that it was against the law.[72]

- Dickson Tan Yong Wen, a Singaporean who received three more strokes than he was sentenced to because of an administrative error. He was sentenced on 28 February 2007 to nine months in jail and five strokes of the cane for two offences involving abetting an illegal moneylender to harass a debtor. However, he received eight strokes on 29 March 2007.[73] Tan sought S$3 million from the government in compensation but was rejected. He did receive some compensation after negotiations, but the amount was kept secret.[74] After the caning error incident, Tan ran into trouble with the law again on two occasions. In both cases, he was jailed but not sentenced to caning.[75][76]

- Dave Teo, a Singaporean Full Time National Serviceman who made headlines in Singapore when he went absent without official leave (AWOL) on 2 September 2007 from an army camp with a SAR 21 assault rifle. He was arrested by the police at Cathay Cineleisure Orchard with the rifle, eight 5.56mm rounds, and a knife in his possession. Teo was sentenced in July 2008 to nine years and two months' imprisonment and 18 strokes of the cane under multiple charges under the Arms Offences Act.[77]

- Mohamad Khalid Mohamad Yusop, who vandalised The Cenotaph, was sentenced to three months' imprisonment and three strokes of the cane in August 2013.[78]

- Alvin Phoon Hui Zhi, a former Youth Olympic Games cyclist sentenced to five years' imprisonment and five strokes of the cane in 2015 for drug trafficking and consumption.[79]

- Goh Eng Kiat, a company director who became the first person to be sentenced to caning for offences committed under Singapore's Employment of Foreign Manpower Act (EFMA). He was sentenced on 3 November 2017 to a total of 50 months' imprisonment and five strokes of the cane for fraudulently obtaining work passes for 30 foreign workers for a company that did not require their employment.[80]

Comparison to other countries

Judicial caning is also used as a form of legal punishment for criminal offences in two of Singapore's neighbouring countries, Brunei and Malaysia. There are some differences across the three countries.

| Brunei | Malaysia | Singapore | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharia caning | Yes | Yes | No |

| Juveniles | Local courts may order the caning of boys below the age of 16. | Local courts may order the caning of boys below the age of 16. | Only the High Court may order the caning of boys below the age of 16. |

| Age limit | Men above the age of 50 cannot be sentenced to caning. | Men above the age of 50 cannot be sentenced to caning. However, the law was amended in 2006 such that men convicted of sex offences may still be sentenced to caning even if they are above the age of 50. In 2008, a 56-year-old man was sentenced to 57 years jail and 12 strokes of the cane for rape.[81] | Men above the age of 50 cannot be sentenced to caning. |

| Maximum no. of strokes per trial | 24 strokes for adults; 18 strokes for juveniles | 24 strokes for adults; 10 strokes for juveniles | 24 strokes for adults; 10 strokes for juveniles |

| Terminology | Officially, whipping, in accordance with traditional British legislative terminology. | Officially, whipping, in accordance with traditional British legislative terminology. Informally, caning; the phrases "strokes of the cane" and "strokes of the rotan" are used interchangeably. | In both legislation and press reports, the term caning refers to the punishment. |

| Dimensions of the cane | About 1.2 m (3.9 feet) long and no more than 1.27 cm (0.5 inches) in diameter | About 1.09 m (3.6 feet) long and no more than 1.25 cm (0.49 inches) in diameter | About 1.2 m (3.9 feet) long and no more than 1.27 cm (0.5 inches) in diameter |

| Type of cane | The same type of rattan cane is used on all offenders regardless of the offence committed. | Two types of rattan canes are used: The smaller one is for white-collar offenders while the larger one is for other offenders. | The same type of rattan cane is used on all offenders regardless of the offence committed. |

| Modus operandi | The offender is tied to a wooden frame in a bent-over position with his feet together. | The offender stands upright at the A-shaped frame with his feet apart and hands tied above his head. He has a special protective "shield" tied around his lower body to cover the lower back and upper thighs while leaving the buttocks exposed. | The offender is tied to the trestle in a bent-over position with his feet together. He has protective padding secured around his lower back to protect the kidney and lower spine area from strokes that land off-target. |

Prison caning

Male convicts who are not sentenced to caning by the courts are still liable to be caned in prison if they commit offences while serving time in prison. The modus operandi is the same as that of judicial caning.

A Superintendent of Prisons may impose corporal punishment not exceeding 12 strokes of the cane for aggravated prison offences.[9] Such offences include engaging in gang activities, mutiny, attempting to escape, destruction of prison property, and assaulting an officer or a fellow prisoner.[83] The punishment is carried out after due inquiry at a "mini-court" inside the prison, during which the prisoner is given an opportunity to hear the charge and evidence against him and present his defence.[84] The Prisons Director must approve the punishment before it can be carried out. Visiting justices may also order an inmate to be given up to 24 strokes of the cane. However, the Prisons Department has confirmed that such cases are rare.[83]

Inmates of Drug Rehabilitation Centres may be caned in the same way.

In 2008, the procedure was revised to introduce a review of each prison caning sentence by an independent external panel.[85]

Military caning

In the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), a subordinate military court, or the officer in charge of the SAF Detention Barracks, may sentence a serviceman to a maximum of 24 strokes of the cane (10 strokes if the serviceman is below 16)[86] for committing certain military offences or for committing aggravated offences while being detained in the Detention Barracks.[87] In all cases, the caning sentence must be approved by the Armed Forces Council before it can be administered.[88] The minimum age for a serviceman to be sentenced to caning is 16 (now 16½ de facto, since entry into the SAF is restricted to those above that age).[89] This form of caning is mainly used on recalcitrant teenage conscripts serving full-time National Service in the SAF.[90]

Military caning is less severe than its civilian counterpart, and is designed not to cause undue bleeding and leave permanent scars. The offender must be certified by a medical officer to be in a fit condition of health to undergo the punishment[91] and shall wear "protective clothing" as prescribed.[92] The punishment is administered on the buttocks, which are covered by a "protective guard" to prevent cuts.[89] The cane used is no more than 6.35 mm (0.25 inches) in diameter (about half the thickness of the prison/judicial cane).[93] During the punishment, the offender is secured in a bent-over position to a trestle similar to the one used for judicial/prison canings.[94]

Reformatory caning

Caning is used as a form of legal corporal punishment in government homes, remand homes, and other homes for children and youth.

Children and youths aged 16 and below alleged to have committed crimes may be placed in remand homes during the period of investigation. If convicted, they may be sent to the state-run reformatories, namely the Singapore Boys' Home and the Singapore Girls' Home, for up to three years. For example, the Singapore Boys' Home holds about 400 inmates aged 11 through 18 who have been sent there by the courts for committing offences such as theft, robbery or rioting, or because they have been deemed to be Beyond Parental Control.[95]

Children whose parents have applied for Beyond Parental Control orders against them are, during the period of investigation, placed in remand homes. They may thereafter be placed in homes which also house juvenile offenders.[96]

The superintendents of reformatories are allowed to impose corporal punishment on both male and female residents as a last resort for serious misconduct. They are required to maintain a record of the details and evidence of the offender's misconduct and their reasons for deciding to cane him/her.[97] Persons with mental or physical disability are exempted from such punishment. Solitary confinement is also permitted for children of and above 12 years of age, except in remand homes.[98]

The punishment is administered in private by the superintendent or an authorised officer of the same sex as the offender, using a cane of a type approved by the Director of Social Welfare. Caning must be carried out in the presence of another staff member. A maximum of ten strokes may be inflicted.[99] The only form of corporal punishment permitted is caning on the palm for both female and male offenders, and on the buttocks over clothing for male offenders only.[100]

In the Singapore Boys' Home, boys are routinely caned on the buttocks for serious offences such as fighting, bullying and absconding. A 2006 article in The Straits Times reported that there were two cases of bullying per month on average; one youth also said that he had been caned over 60 times in three years at the Singapore Boys' Home.[101] A former SBH resident, who received 10 strokes for absconding when he was 18, said that his buttocks took two weeks to heal sufficiently before he could sit down properly.[102]

In the Singapore Girls' Home, punishments for serious offences may include solitary confinement in a windowless room, as well as caning on the palm.[103]

Apart from the Singapore Boys' Home and Singapore Girls' Home, there are other juvenile institutions managed by voluntary welfare organisations, such as the Boys Town operated by the Montfort Brothers of St. Gabriel for boys of ages 11 to 21.[102] Although these juvenile institutions are legally allowed to administer corporal punishment in the same way as the state-run reformatories, they must obtain the management committee's authorisation before carrying it out.[99]

School caning

Caning is a legal disciplinary measure in primary and secondary schools, junior colleges and centralised institutes.[104] It is permitted for male students only. Female students receive alternative forms of punishment, like detention(s), Corrective Work Order(s) or suspension(s).[105][106][107][108]

The punishment may be administered only by the Principal or any staff member under the Principal's express authority, usually the Vice Principal, Discipline Master, Operations Manager, or any other legally authorised member of the school's Disciplinary Committee. The offending student's parents or guardians must be informed immediately of the offence and the punishment. Some schools may seek parental or guardian consent before administering the punishment.[109][110][111]

The Ministry of Education (MOE) states that corporal punishment is allowed for serious or repeated misconduct under the Education (Schools) Regulations, and adds that counselling and follow-up guidance should be carried out.[112] At most schools, caning comes after detention but before suspension in the hierarchy of penalties. Some schools implement a demerit points system, in which students receive mandatory caning after accumulating a certain number of demerit points for a wide range of misconduct. The possibility of caning as a corrective action is often explicitly stated in schools' student handbooks or on their websites. As of 2018, 13% of primary schools and 53% of secondary schools (excluding all-girls schools) communicated on their websites that caning may be administered to male students for serious misconduct.[111]

Under MOE regulations, a maximum of three strokes (previously six strokes)[111] may be inflicted using a light rattan cane. The student may be caned only on either the palm of the hand or the buttocks over clothing.[109][110] Although boys of any age from six to 19 may be caned, the majority of canings are of secondary school students aged 14 to 16 inclusive.[111]

A solemn and formal ceremony, school caning is typically carried out in a manner similar to the canings administered in English schools before school corporal punishment was banned in England in 1998. Some schools tuck a protective item (e.g. book, file, rolled-up newspaper, piece of cardboard) into the student's waistband to protect his lower back in case a stroke lands off-target. The student then places his hands on a desk or chair, bends over or leans forward, and receives strokes from the rattan cane on the seat of his trousers or shorts.[111]

Based on first-hand accounts, the student typically feels moderate to acute pain for the first few minutes, depending on the number of strokes. This soon leads to a stinging sensation and general soreness around the points of impact, usually lasting for some hours; sitting down is likely to be uncomfortable. Superficial bruises and weals may appear on the buttocks and last for a few days after the punishment.[111]

Although caning on the palm of the hand is rarely implemented, one notable exception is Saint Andrew's Secondary School, where students may be caned on the hand for committing less serious offences while a caning on the buttocks is reserved for more serious offences.[113]

Canings in school may be sorted into these categories:[111]

- Private caning: The most common form of school caning. The offending student is caned in the school's General Office in the presence of the Principal and/or Vice Principal and another witness (usually the student's form teacher). His parents or guardians may be invited to the school to witness the punishment being meted out.

- Class caning: The offending student is caned in front of his class.

- Public caning: The offending student is caned in front of an assembly of the entire school population to serve as a warning for potential offenders. This form of punishment is normally reserved for very serious offences and repeated offences. Common offences that warrant a public caning include smoking, consumption of alcohol, drug or gang-related activities, fighting, vandalism, and theft.[114]

- Others: There may be intermediate levels between a "class caning" and a "public caning", such as in front of all classes in the same year as the student.

Certain schools adopt special practices. For example, following English traditions, some schools (mainly all-boys schools) require the student to change into physical education (PE) attire for the punishment because PE shorts are apparently thinner than normal uniform trousers/shorts, even though the main purpose is probably to enhance the formality of the occasion. In some schools, if the caning is conducted in public, the student is required to make a public apology before or after receiving his punishment.[111]

Routine school canings are normally not publicised, so only rare and special cases are reported in the media.[111]

As Singapore evolves, some citizens may perceive that schools are refraining from corporal punishment due to their fears of a strong backlash from parents.[115] Educators, when interviewed, say that they are cognisant of Singapore's changing landscape, both in terms of the family structure as well as the influence of social media, in the reduction of corporal punishment in schools. They note that understanding and accepting such punishment is essential to the effectiveness of caning as a deterrent of misconduct.[116] According to a Singaporean legal advice website, as long as schools administer corporal punishment according to MOE guidelines, parents may not take legal action against the school as they are not direct employers of the school.[117]

Parental caning

Caning is also meted out on children (both boys and girls) by their parents as punishment for offences like poor/imperfect results,[118][119] disrespect,[120] disobedience, lying,[121] and trying to escape caning.[118]

The misbehaving child is usually caned on the buttocks or palms. Sometimes, the cane will miss and hit the thighs/calves, causing more pain.[122]

The caning usually leaves the child with painful red welts[119] that will fade within days.

The most commonly used implement is the rattan cane, commonly and cheaply found (for around 50 Singapore cents) in neighbourhood provision shops. There is usually higher demand when students prepare for examinations, and the cane would be used more often, resulting in breakages.[123] Sometimes, parents will use other implements such as the rattan handle of a feather-duster, rulers, clothes hangers,[124] or even their bare hands.[125]

This form of punishment is legal in Singapore, but not particularly encouraged by the authorities, and parents are likely to be charged with child abuse if the child is injured.[126]

According to a survey conducted by The Sunday Times in January 2009, 57 percent of surveyed parents said that caning was an acceptable form of punishment and they had used it on their children.[127] A newer study conducted by YouGov in 2019 found that nearly 80 percent of parents in Singapore had carried/carries out corporal punishment at home.[128]

Public opinion on caning in Singapore

- Judicial caning

Judicial caning is meant to serve as a humiliating experience for offenders and as a strong deterrent to crime. In 1966, when Singapore's first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, introduced caning as a mandatory punishment for vandalism, he said in Parliament, "[...] if (the offender) knows he is going to get three of the best, I think he will lose a great deal of enthusiasm, because there is little glory attached to the rather humiliating experience of having to be caned."[129]

In a 2004 interview with China Central Television, Lee explained why caning should continue in Singapore with reference to the 1994 Michael Fay incident: "Every country has its own problems to face, we know, certain things. You put a person in a prison, it makes no difference. He will not change. Because you observe certain rules, there's enough food, enough exercise, fresh air, sunshine ... But if you cane him, and he knows he will be given six of the best on his buttocks, and it will hurt for one week that he can't sit down comfortably, he will think again."[130]

Although the extensive use of judicial caning is a policy commonly associated with the ruling People's Action Party (PAP), the opposition parties do not oppose it because they agree on its effectiveness as a deterrent to crime.[131] Politicians from the opposition parties have voiced support for corporal punishment. Edmund Ng, a candidate for the Singapore Democratic Alliance in the 2006 general election, said, "For criminals, caning serves as a deterrent [...] I would not change a winning formula."[132] Sylvia Lim, a Member of Parliament from the Workers' Party, also said in 2007, "What are the purposes of jail, fine and caning? Caning is controversial internationally, but if one must justify why we cane offenders, it is just deserts for pain which the offender has caused to the victim, for example, hurt, injury or the threat of violence. Caning is a severe punishment, and it is always combined with jail as the offences tend to be serious and to make it easier, administratively, to arrange for the caning to take place."[133]

The severity and humiliation of the punishment are widely publicised in various ways, mainly through the press but also through other means such as education. For example, juvenile delinquents get to watch a real-life demonstration of caning on a dummy during compulsory prison visits.[131]

Singapore has come under strong international criticism for its practice of judicial caning, especially after the 1994 Michael Fay incident. Amnesty International condemned the practice of judicial caning in Singapore as a "cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment".[134] It is also regarded by some international observers as a violation of Article 1 in the United Nations Convention against Torture. However, Singapore is not signatory to the Convention.[135] Human Rights Watch similarly referred to the practice of caning as "an inherently cruel punishment".[136]

The Singaporean government has defended its stance on judicial caning and said that the punishment does not amount to torture and is conducted under strict standards and medical supervision.[137] While most Singaporeans either support or are indifferent towards the practice of judicial caning, there is a minority – including dissident Gopalan Nair,[138] lawyer M Ravi[64] and businessman Ho Kwon Ping – who are completely or partially opposed to it.[139]

A recipient of nine strokes thinks that even though it may be a nightmare the first time, an offender who has been caned before will have experienced the extent of fear of criminal punishment and so may not find it as much of a disincentive to commit repeat offences. He said, "After he knows what it's like, he will have nothing left to fear. He will know what to expect no matter how many strokes he gets – it's more of the same. No alcohol and women – apart from those two things, prison is really not that bad."[39]

- School caning

Critics argue that since Singapore is a member of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, it is therefore obliged to "take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse". However, the Singaporean government stated that it considers "the judicious application of corporal punishment in the best interest of the child."[140]

In arts and media

Media

- Behind Bars, a 1991 Singaporean television series produced by the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation in collaboration with the Singapore Prison Service. The drama portrays the lives of prison officers and convicts in prison. In two episodes, two convicts are separately punished by caning for breaking prison rules.

- Prison Me? No Way!, a 15-minute video commissioned by the National Crime Prevention Council to deter teenagers from crime. The video, filmed in Changi Prison and Changi Reformative Training Centre at a cost of S$43,000, shows life in prison from the perspectives of two young offenders and includes a reenactment of a judicial caning. It was distributed to over 140 schools in October 1998.[141]

- Love is Beautiful, a 2003 Singaporean television series produced by MediaCorp Channel 8. In the drama, Huang Leshan (Andrew Seow) is sentenced to 18 years' imprisonment and 12 strokes of the cane for raping Song Hui (May Phua). The caning scene is briefly shown in one of the episodes when Huang Leshan recalls his ordeal.

- One More Chance,[142] a 2005 Singaporean film by Jack Neo which portrays the lives of three convicts in prison. It also reflects the social stigma towards ex-offenders. In one scene, one of the three convicts (Henry Thia) receives his caning sentence of six strokes.

- I Not Stupid Too,[143] a 2006 Singaporean film by Jack Neo which reflects the lives of three ordinary Singaporean youngsters in school and their relationships with their families. One of the main characters, Tom Yeo (Shawn Lee), is publicly caned in school for possessing an obscene video disc and assaulting his teacher. The caning scene is graphically portrayed, with Tom bending over a desk on the stage in the school hall to receive three hard strokes on the seat of his trousers in front of the assembled student body. This faithfully reproduced the procedure used in real life at the school where the scene was filmed, Presbyterian High School. The public caning issue sparked off a debate in which it was revealed that some Singaporeans were not aware that corporal punishment is common in secondary schools.

- The Homecoming,[144] a 2007 Singaporean television series produced by MediaCorp. In the drama, four men were convicted of arson in their youth and sentenced to imprisonment and three strokes of caning each. One of them (Rayson Tan) received one more stroke than either of his three friends, supposedly for being the mastermind. Several years later when he becomes a successful lawyer, he sets off to find out who betrayed him and takes his revenge. The caning scene is featured briefly in flashbacks.

- Don't Stop Believin', a 2012 Singaporean television series produced by MediaCorp. In the drama, a secondary school student, Zhong Junliang (Xu Bin), is wrongly accused of molesting a female student. He is caned in front of the school assembly by the discipline master (Brandon Wong), who turns out to be his father.

- Ilo Ilo, a 2013 Singaporean family film directed by Anthony Chen. In one scene, the main character Jiale (Koh Jia Ler) receives a public caning in school for fighting with his classmate.

- Chandi Veeran, a 2015 Indian film directed by A. Sarkunam. In the scene after the opening credits, the protagonist Paari (Atharvaa) receives three strokes of the cane in a Singaporean prison.

- Take 2, a 2017 Singaporean comedy film about the lives of four ex-convicts, directed by Ivan Ho and produced by Jack Neo. In the prologue, the four (Ryan Lian, Wang Lei, Gadrick Chin and Maxi Lim) receive their caning sentences.

- Rotan, a 2017 Singaporean short film shown at the Singapore International Film Festival 2017 and directed by Hamzah Fansuri. The film is about a father, who is also the discipline master at his son's school, having to uphold his own principles and punish his rebellious son for breaking the school rules.[145]

Literature

- The Caning of Michael Fay: The Inside Story by a Singaporean (1994),[146] a documentary book by Gopal Baratham published in the wake of the controversial caning of Michael P. Fay. It concentrates on the personal aspects, the punishment and the sociology of caning in Singapore. The book includes some descriptions of caning and photographs of its results, as well as two personal interviews with men who had been caned before.

- The Flogging of Singapore: The Michael Fay Affair (1994) by Asad Latif.[147]

See also

References

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #The History of Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei". World Corporal Punishment Research. January 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Ratification status Archived 11 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the website of the UN.

- Criminal Procedure Code section 331.

- Criminal Procedure Code section 328.

- Thomas, Sujin (12 December 2008). "24-stroke caning cap to be formalised". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Criminal Procedure Code section 330.

- Criminal Procedure Code section 329.

- "Yong Vui Kong v Public Prosecutor [2015] SGCA 11". SingaporeLaw.sg. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Prisons Act section 71.

- Criminal Procedure Code section 325(1).

- Criminal Procedure Code sections 325–332.

- Chelvan, Vanessa Paige (9 May 2017). "Jail terms for those excused from caning should not be 'automatically' raised: High Court". Channel News Asia. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- Narayan, Lakshmi (24 December 2012). "Wield the rod, stem the rot". The Asian Age. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Singapore: Judicial and prison caning: Table of offences for which caning is available". World Corporal Punishment Research. 2011. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Immigration Act section 15(3b).

- Rajah, Jothie (April 2012). Authoritarian Rule of Law: Legislation, Discourse and Legitimacy in Singapore. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107634169.

- Vandalism Act, section 3.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Offences for which caning is imposed". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "These 6 were caned for hiring illegals". The Straits Times. Singapore. 3 July 1998. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Control of Manufacture Act sections 8–9.

- "Singapore Human Rights Practices, 1994". Electronic Research Collections. U.S. Department of State. February 1995. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Singapore". U.S. Department of State. 11 March 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Singapore". U.S. Department of State. 6 March 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "2008 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "2009 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "2010 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. 8 April 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "2011 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2014: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2015: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #How many strokes are given". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- "How a Prisoner is Caned". The Straits Times. Singapore. 1 May 1994.

- Raman, P.M. (13 September 1974). "Branding the Bad Hats for Life". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Von Mirbach, Johan (5 March 2015). "The invisible scars left by strikes of the cane". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "Striking fear into hearts of most hardened criminals". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur. 27 May 2004. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Prisons Regulations section 139(1).

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Procedure in Detail". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Tan, Jeanette (6 July 2018). "S'porean gang leader served 10 years' jail, got 9 strokes of cane, & now has own pottery exhibition". Mothership. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- kAi (23 September 2008). "My Story 第五部". Abunehneh. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Prisons Regulations section 98(1).

- "'No advance notice' for caning". The Straits Times. Singapore. 4 May 1994. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- John, Arul; Chan, Crystal (1 July 2007). "Prisoners given chance to confirm sentence beforehand". The New Paper. Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Apparatus used". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Prisons Regulations section 139(2).

- Viyajan, K.C. (30 June 2007). "Vandal caned three strokes more than ordered". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Criminal Procedure Code section 332.

- "Fay describes caning, seeing resulting scars". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. 26 June 1994. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #The Immediate Physical Effects". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Yaw, Yan Chong; Ang, Dave (10 September 1991). "Don't imitate us". The New Paper. Singapore.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Descriptions of the Experience by Men Who Have Been Caned". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Ng, Irene; Poh, Ambrose (12 October 1988). "My Ordeal in the Cane Room". The New Paper. Singapore.

- Baratham, Gopal (1994). The Caning of Michael Fay: The Inside Story by a Singaporean. Singapore: KRP Publications. p. 81.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Medical Treatment". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #After Effects: The Healing of the Wounds". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "NZ soldiers fail in appeal for clemency". The Straits Times. Singapore. 17 April 1982. p. 8. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Joshi, Vijay (6 September 1994). "Hong Kong Boy Released From Jail After Caning – Accused Of Vandalism, Teen Spent Months In Jail". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "New Zealand Man Caned in Singapore". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 12 December 1997. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "Caning bearable". The Press. Christchurch, New Zealand. 15 December 1997. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Chong, Elena (8 July 2008). "Swiss vandal gets 5 months, 3 strokes". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Another Taiwanese loansharking offender ordered to be jailed, caned". Today. Singapore. 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Lim, Yvonne (29 November 2014). "Little India riot: Man gets 3 strokes of the cane for instigating crowd". Today. Singapore. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Tan, Su-Lin (6 March 2015). "Singapore court sentences two German vandals to nine months in prison and caning". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Lum, Selina (23 August 2014). "Drug courier's lawyer challenges caning sentence". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Lim, Yvonne (5 March 2015). "Caning not unconstitutional: Apex court". Today. Singapore. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Chelvan, Vanessa Paige (4 February 2017). "Saudi diplomat sentenced to 26 months' jail, caning for molesting hotel intern". Channel News Asia. Singapore. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Lum, Selina (21 July 2017). "Saudi diplomat who molested hotel intern loses appeal against conviction and sentence". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Lum, Selina (15 August 2017). "British trio sentenced to 5½- 6½ years with caning for aggravated molestation". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Chua, Alfred (6 December 2017). "MD of horse-racing company gets jail, caning for molesting two women in Boat Quay bars". Today. Singapore. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Tang, Louisa (15 January 2019). "British drug trafficker who faces 24 strokes of the cane must bear consequences of committing offences in S'pore: MHA". Today. Singapore. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Nair, Suresh (5 June 1991). "I got 48 instead of 24 strokes". The New Paper. Singapore.

- "Are these ex-cons jumping on the bandwagon to get a big pay-off?". The New Paper. Singapore. 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- "3 extra strokes for prisoner: Govt regrets error". The Straits Times. Singapore. 1 July 2007. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Vijayan, K.C. (20 August 2008). "Caning error: Ex-inmate accepts mediated settlement". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Leong, Wee Keat (30 December 2008). "Dickson Tan in trouble with the law – again". Today. Singapore. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Poh, Ian (1 December 2014). "Man stabbed party-goer in eye with tongs during bar fight; jailed nine months". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- "Judge tells soldier who took rifle out of camp: 'My heart hurts for you'". The Straits Times. Singapore. 8 July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Chong, Elena (27 August 2013). "Cenotaph vandal gets 3 months' jail and 3 strokes". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Cheong, Danson (24 July 2015). "Ex-YOG cyclist gets jail, cane for drug offences". The Straits Times. Singapore. p. A8. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "Company director becomes first person to get caning for fraudulently obtaining work passes". Channel News Asia. Singapore. 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "57 years jail and 12 strokes for raping relative". The Star. Kuala Lumpur. 30 April 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Some Differences Between Singapore and Malaysia". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Yeo, Andre (20 August 2007). "Commit a serious offence in prison? You risk a caning". The New Paper. Singapore. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Prisons Act section 75.

- Teh Joo Lin (15 September 2008). "New check on punishing prisoners". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(2).

- Singapore Armed Forces Act section 119(1).

- Singapore Armed Forces Act section 119(2).

- "Singapore: Caning in the military forces". World Corporal Punishment Research. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Murder charge soldiers can be court-martialled". The Straits Times. Singapore. 30 July 1975. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(5).

- Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(6).

- Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(4).

- Singapore Armed Forces (2006). "Pride, Discipline, Honour" (book commemorating 40th anniversary of the SAF Military Police Command).

- Lim, Hui Min (2014). Juvenile Justice: Where Rehabilitation Takes Centre Stage. Singapore: Academy Publishing. ISBN 9810790953.

- BSS, ‘Areas for Advocacy,’ February 2010, accessed 8 May 2012, http:// www.beyondresearch.sg/report/Doc_C_-_Sam_Tang.PDF, 9.

- Children and Young Persons (Remand Home) Regulations section 21(1–2).

- Children and Young Persons (Government Homes) Regulations 2011 (Cap 38, Reg 22-24, 2001 Rev Ed Sing), reg 22-24; Children and Young Persons (Licensing of Homes) Regulations 2011 (Cap 38, Reg 25-27, 2001 Rev Ed Sing), reg 25-27; Children and Young Persons (Remand Homes) Regulations 2001 (Cap 38, Reg 20-21, 1993 Rev Ed Sing), reg 20-21.

- Children and Young Persons (Licensing of Homes) Regulations 2011 section 27.

- Children and Young Persons (Remand Home) Regulations section 21(3).

- Fong, Tanya; Yap, Su-Yin (20 November 2006). "Boy's Home: When some don't make good". The Straits Times. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- "Singapore: Reformatory CP". World Corporal Punishment Research. April 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Goh, Jolene (10 October 2012). Jolene's Story. Marshall Cavendish International Asia. ISBN 978-981-4408-99-8.

- "Education (Schools) Regulations". Singapore Statutes Online. Attorney-General Chambers, Singapore. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Singapore: Muslim Schoolgirls Suspended For Wearing Headscarves". MuslimVillage.com. 7 February 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Unantenne, Nalika (22 October 2013). "Is punishment in schools in Singapore too extreme?". sg.theasianparent.com. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "CANING, PADDLING AND SPANKING: OFFICIAL RULES FROM CURRENT SCHOOL HANDBOOKS - page 6". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Should schools spare the rod when it comes to caning girls?". The New Paper. Singapore. 3 December 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Education (Schools) Regulations section 88.

- "School Principals' Handbook, Section 19". World Corporal Punishment Research. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Singapore: Corporal punishment in schools". World Corporal Punishment Research. January 2019. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "MOE and Schools are Committed to Maintaining High Standards of Discipline in Schools". Forum Reply. Ministry Of Education. 19 May 2014.

- "Structure of Discipline Committee (2005) - 2013_Discipline_Rule_Book.pdf" (PDF). Saint Andrew's Secondary School. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Husna, Nabilah (20 June 2019). "Do Singaporeans think of children as people?". Medium. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "Time for corporal punishment in schools?". All Singapore Stuff.

- "Six Discipline Questions Answered". School Bag: the Education News Site. Ministry of Education. 14 January 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Caning in Singapore: Judicial, School & Parental Corporal Punishment". Singapore Legal Advice. 22 April 2019.

- Team, Goody Feed (3 July 2018). "9 Things Non-Strawberries Remember About the Cane That Strawberries Won't Understand". Goody Feed. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Study Hard and Graudate, Otherwise Kena Rotan! But After That... How?". RedWire Times Singapore. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "What's wrong with caning our kids?". The Pride. 31 May 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Mathi, Braema; Andrianie, Siti (11 April 1999). "Spare your child the rod? No". The Sunday Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Team, Goody Feed (3 July 2018). "9 Things Non-Strawberries Remember About the Cane That Strawberries Won't Understand". Goody Feed. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Kids say: What works for them". The Sunday Times. Singapore. 11 April 1999. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Hun, Boon (26 May 2017). "S'pore Mother Filmed Caning Daughter in Public Apologises, Says She'll Go Counselling". Goody Feed. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "Punishment or abuse? Video of Singaporean man slapping kneeling girl in public goes viral". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Lam, Lydia (6 December 2018). "Jail for father who beat 9-year-old son with hanger over homework". Channel News Asia. Singapore. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Sudderuddin, Shuli (13 January 2009). "To cane or not to cane..." The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Teng, Amelia (30 July 2019). "Most parents here don't spare rod on kids at home: Study". The Straits Times. Singapore. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (26 August 1966) vol 20 at cols 291–305.

- "Conversation with LKY (CCTV) Part 1/2 (June 2004)". Youtube. 7 October 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Humiliation and deterrence". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "We posed the same questions to two Singapore Democratic Alliance candidates". The New Paper. Singapore. 12 April 2006.

- Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (22 October 2007) vol 83 at cols 2175–2242.

- "Singapore – Amnesty International Report 2008". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Republic of Singapore Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review" (PDF). International Harm Reduction Association. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "World Report 2014: Singapore #Criminal Justice System". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Parameswaran, Prashanth (10 March 2015). "Singapore Defends Caning". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Nair, Gopalan (12 August 2014). "Singapore orders brutal beating (caning) of anti-government graffiti artist". Singapore Dissident. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Ho, Kwon Ping (6 February 2015). "The next 50 years of Singapore's security and how NS, ISA and caning need to change". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Ratification status Archived 11 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the website of the United Nations.

- Chong, Chee Kin (7 October 1998). "Watch this and stay off crime". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- San ge hao ren on IMDb

- Xiaohai bu ben 2 on IMDb

- Teo, Wendy (3 April 2007). "Rayson Tan bares his bum for the first time in new Channel 8 drama, only to become... The butt of jokes". The New Paper. Singapore. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Singapore Panorama: Short Film Programme 1". 2017 Singapore International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Baratham, Gopal (1994). The Caning of Michael Fay. Singapore: KRP Publications. ISBN 981-00-5747-4.

- Latif, Asad (1994). The Flogging of Singapore: The Michael Fay Affair. Singapore: Times Books International. ISBN 981-204-530-9.