Spanking

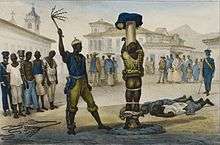

Spanking is a common form of corporal punishment, involving the act of striking the buttocks of another person to cause physical pain, generally with an open hand. More severe forms of spanking, such as switching, paddling, belting, caning, whipping, and birching, involve the use of an object instead of a hand.

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

Parents commonly spank children or adolescents in response to undesired behavior.[1][2] Adults more commonly spank boys than girls, both at home and in school.[3] Some countries have outlawed the spanking of children in every setting, including homes, schools, and penal institutions,[4] but most allow it when done by a parent or guardian.

Terminology

In North America, the word "spanking" has often been used as a synonym for an official paddling in school,[5] and sometimes even as a euphemism for the formal corporal punishment of adults in an institution.[6]

In British English, most dictionaries define "spanking" as being given only with the open hand.[7] Flagellation was so common in England as punishment that spanking (and caning and whipping) are called "the English vice".[8]

In American English, dictionaries define spanking as being administered with either the open hand or an implement such as a paddle.[9] Thus, the standard form of corporal punishment in US schools (use of a paddle) is often referred to as a spanking.

In the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand, the word "smacking" is generally used in preference to "spanking" when describing striking with an open hand, rather than with an implement. Whereas a spanking is invariably administered to the bottom, a "smacking" is less specific and may refer to slapping the child's hands, arms or legs as well as its bottom.[10]

In the home

_-_n._202a.jpg)

Parents commonly spank their children as a form of corporal punishment in the United States; however, support for this practice appears to be declining amongst U.S. parents.[1][11] Spanking is typically done with one or more slaps on the child's buttocks with a bare hand, although, not uncommonly, various objects are used to spank children.[1] Historically, adults spank boys more than girls.[3][12] In the United States, adults commonly spank infants and toddler age children are spanked the most.[13] The main reasons parents give for spanking children are to make children more compliant and to promote better behavior, especially to put a stop to children's aggressive behaviors.

However, research has shown that spanking (or any other form of corporal punishment) is associated with the opposite effect.[1][11] When adults physically punish children, the children tend to obey parents less with time and develop more aggressive behaviors, including toward other children.[1] This increase in aggressive behavior appears to reflect the child's perception that hitting is the way to deal with anger and frustration.[1] There are also many adverse physical, mental, and emotional effects correlated with spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, including various physical injuries, increased anxiety, depression, and antisocial behavior.[1][14][15] Adults who were spanked during their childhood are more likely to abuse their children and spouse.[1]

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) all recommend that no child should be spanked and instead favor the use of effective, healthy forms of discipline.[1][11][16][17] Additionally, the AAP recommends that primary care providers (e.g., pediatricians and family medicine physicians) begin to discuss parents' discipline methods no later than nine months of age and consider initiating such discussions by age 3–4 months.[1] By eight months of age, 5% of parents report spanking and 5% report starting to spank by age three months.[1] The AAP also recommends that pediatricians discuss effective discipline strategies and counsel parents about the ineffectiveness of spanking and the risks of harmful effects associated with the practice to minimize harm to children and guide parents.[11][18]

Although parents and other advocates of spanking often claim that spanking is necessary to promote child discipline, studies have shown that parents tend to apply physical punishment inconsistently and tend to spank more often when they are angry or under stress.[19] The use of corporal punishment by parents increases the likelihood that children will suffer physical abuse,[1] and most documented cases of physical abuse in Canada and the United States begin as disciplinary spankings.[20] If a child is frequently spanked, this form of corporal punishment tends to become less effective at modifying behavior over time (also known as extinction).[1] In response to decreased effectiveness of spanking, some parents increase the frequency or severity of spanking or use an object.[1]

Alternatives to spanking

Parents may spank less - or not at all - if they have learned effective discipline techniques, since many parents view spanking as a method of last resort to discipline their children.[11] There are many alternatives to spanking and other forms of corporal punishment:

- Time-in, increasing, praise, and special time to promote desired behaviors

- Time outs to take a break from escalating misbehavior

- Positive reinforcement of rewarding desirable behavior with a star, sticker, or treat

- Implementing non-physical negative reinforcement in which an unpleasant consequence follows misbehavior, such as taking away a privilege

- Ignoring low-level misbehaviors and prioritizing attention on more significant forms of misbehavior

- Avoiding the opportunity for the misbehavior to occur and thus the need for corrective discipline.[1]

In schools

Corporal punishment, usually delivered with an implement (such as a paddle or cane) rather than with the open hand, used to be a common form of school discipline in many countries, but it is now banned in most of the Western World.

Corporal punishment, such as caning, remains a common form of discipline in schools in several Asian and African countries, even in countries in which this practice has been deemed illegal such as India and South Africa.[21][22][23] In these cultures it is referred to as "caning" and not "spanking."

The Supreme Court of the United States in 1977 held that the paddling of school students was not per se unlawful.[24] However, 31 states have now banned paddling in public schools. It is still common in some schools in the South, and more than 167,000 students were paddled in the 2011-2012 school year in American public schools.[25] Students can be physically punished from kindergarten to the end of high school, meaning that even adults who have reached the age of majority are sometimes spanked by school officials.[26]

A number of medical, pediatric or psychological societies have issued statements opposing all forms of corporal punishment in schools, citing such outcomes as poorer academic achievements, increases in antisocial behaviors, injuries to students, and an unwelcoming learning environment. They include the American Medical Association,[27] the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,[28] the American Psychoanalytic Association,[29] the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP),[30][31] the Society for Adolescent Medicine,[32][33] the American Psychological Association,[34] the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health,[35][36] the Royal College of Psychiatrists,[37] the Canadian Paediatric Society[38] and the Australian Psychological Society,[39] as well as the United States' National Association of School Psychologists and National Association of Secondary School Principals.[40][41]

Adult spanking

Men spanking their wives and girlfriends was often seen as an acceptable form of domestic discipline in the early 20th century as a way to correct behavior, maintain male dominance, and enforce gender norms. It was a common trope in American films.[42] In the early 21st century, adherents of a small subculture known as Christian domestic discipline rely on a literalist interpretation of the Bible to justify spanking as a form of punishment of women by their husbands.[43] Critics describe such practices as a form of domestic abuse.[44] Some consider it a simple sexual fetish and an outlet for sadomasochistic desires.[45] Christian conservative radio host Bryan Fischer said to the Huffington Post that it was a "horrifying trend – bizarre, twisted, unbiblical and un-Christian".[46]

Ritual spanking traditions

There are some rituals or traditions which involve spanking. For example, on the first day of the lunar Chinese new year holidays, a week-long 'Spring Festival', the most important festival for Chinese people all over the world, thousands of Chinese visit the Taoist Dong Lung Gong temple in Tungkang to go through the century-old ritual to get rid of bad luck. Men traditionally receive spankings and women get whipped, with the number of strokes to be administered (always lightly) by the temple staff being decided in either case by the god Wang Ye and by burning incense and tossing two pieces of wood, after which all go home happily, believing their luck will improve.[47]

On Easter Monday, there is a Slavic tradition of spanking girls and young ladies with woven willow switches (Czech: pomlázka; Slovak: korbáč) and dousing them with water.[48][49][50]

In Slovenia, there is a jocular tradition that anyone who succeeds in climbing to the top of Mount Triglav receives a spanking or birching.[51]

See also

- UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Spanking implements

References

Notes

- Zolotor, AJ (October 2014). "Corporal punishment". Pediatric Clinics of North America (Review). 61 (5): 971–8. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2014.06.003. PMID 25242709.

- Sylvester, Foster, Charles Herbert, Ellsworth D. (1919). "The New Practical Reference Library, Volume 2". The New Practical Reference Library. 2.

- Straus, Murray A.; Douglas, Emily M.; Madeiros, Rose Ann (2013). The Primordial Violence: Spanking Children, Psychological Development, Violence, and Crime. New York: Routledge. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-1848729537.

- "States which have prohibited all corporal punishment". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

- E.g. "Corporal punishment — spanking or paddling the student — may be used as a discipline management technique .... The instrument to be used in administering corporal punishment shall be approved by the principal or designee".Texas Association of School Boards – Standard Code of Conduct wording. Archived 25 June 2007 at Archive.today

- See e.g. Evidence of Colonel G. Headly Basher, Deputy Minister for Reform Institutions, Ontario, Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons on Capital and Corporal Punishment and Lotteries, Canada, 1953–55.

- Oxford English Dictionary: "Spank: To slap or smack (a person, esp. a child) with the open hand." Collins English Dictionary: "Spank: To slap or smack with the open hand, esp. on the buttocks."

- Thomas Edward Murray; Thomas R. Murrell (1989). The Language of Sadomasochism: A Glossary and Linguistic Analysis. ABC-CLIO. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-313-26481-8.

- American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: "Spank: To slap on the buttocks with a flat object or with the open hand, as for punishment."

- Oxford English Dictionary: "Smack: To strike (a person, part of the body, etc.) with the open hand or with something having a flat surface; to slap. Also spec. to chastise (a child) in this manner and fig."

- Sege, RD; Siegel, BS; Council on Child Abuse and Neglect; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (December 2018). "Effective Discipline to Raise Healthy Children". Pediatrics (Review). 142 (6): e20183112. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3112. PMID 30397164.

- Elder, G.H.; Bowerman, C. E. (1963). "Family Structure and Child Rearing Patterns: The Effect of Family Size and Sex Composition". American Sociological Review. 28 (6): 891–905. doi:10.2307/2090309. JSTOR 2090309.

- Straus, Murray A. (Spring 2010). "Prevalence, Societal Causes, and Trends in Corporal Punishment by Parents in World Perspective" (PDF). Law and Contemporary Problems. Duke University School of Law. 73 (2).

Figure 1. Corporal Punishment Begins With Infants, Is Highest For Toddlers, And Continues Into The Teen Years For Many Children

- Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (September 2013). "Spanking and Child Development: We Know Enough Now to Stop Hitting Our Children". Child Development Perspectives. The Society for Research in Child Development. 7 (3): 133–137. doi:10.1111/cdep.12038. PMC 3768154. PMID 24039629.

- MacMillan, HL; Mikton, CR (September 2017). "Moving research beyond the spanking debate" (PDF). Child Abuse & Neglect. 71: 5–8. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.012. PMID 28249733.

- "Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Position Statement on corporal punishment" (PDF). rcpch.adlibhosting.com. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

- "Position Statement: Physical Punishment of Children" (PDF). www.racp.edu.au. The Royal Australasian College of Physicians.

- Orentlicher, David (1998). "Spanking and Other Corporal Punishment of Children by Parents: Undervaluing Children, Overvaluing Pain". Houston Law Review. 38: 147.

- Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health (April 1998). "Guidance for effective discipline". Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics. 101 (4 Pt 1): 723–8. doi:10.1542/peds.101.4.723. PMID 9521967.

- Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (Spring 2010). "More Harm Than Good: A Summary of Scientific Research on the Intended and Unintended Effects of Corporal Punishment on Children". Law & Contemporary Problems. Duke University School of Law. 73 (2): 31–56.

- Pak, Jennifer (5 April 2014). "Malaysia's love for the cane is questioned". BBC News.

- "Corporal punishment 'widespread' in Indian schools". BBC News. 25 October 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Seale, Lebogang (7 October 2017). "Severe corporal punishment still carried out at many SA schools". IOL. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Ingraham v. Wright, 97, S.Ct. 1401 (1977).

- Anderson, Melinda D. (15 December 2015). "The States Where Teachers Can Still Spank Students". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- C. Farrell (October 2016). "Corporal punishment in US schools". www.corpun.com.

- "H-515.995 Corporal Punishment in Schools". American Medical Association.

- "Corporal Punishment in Schools". American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. September 2014.

- "Position Statement on Corporal/Physical Punishment" (PDF). www.apsa.org. American Psychoanalytic Association.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on School Health (February 1984). "Corporal punishment in schools". Pediatrics. 73 (2): 258. PMID 6599942.

- Stein, M.T.; Perrin, E.L. (April 1998). "Guidance for effective discipline. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health". Pediatrics. 101 (4 Pt 1): 723–8. doi:10.1542/peds.101.4.723. PMID 9521967.

- Greydanus, D.E.; Pratt, H.D.; Spates, Richard C.; Blake-Dreher, A.E.; Greydanus-Gearhart, M.A.; Patel, D.R. (May 2003). "Corporal punishment in schools: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine" (PDF). J Adolesc Health. 32 (5): 385–93. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00042-9. PMID 12729988. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009.

- Corporal Punishment, Committee Ad Hoc; Greydanus, Donald E.; Pratt, Helen D.; Greydanus, Samuel E.; Hofmann, Adele D.; Tsegaye-Spates, C. Richard (May 1992). "Corporal punishment in schools. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine". J Adolesc Health. 13 (3): 240–6. doi:10.1016/1054-139X(92)90097-U. PMID 1498122.

- "Corporal Punishment". Council Policy Manual. American Psychological Association. 1975.

- "Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Position Statement on corporal punishment" (PDF). November 2009.

- Lynch, M. (September 2003). "Community pediatrics: role of physicians and organizations". Pediatrics. 112 (3 Part 2): 732–4. doi:10.1542/peds.112.3.S1.732 (inactive 22 January 2020). PMID 12949335.

- "Memorandum on the Use of Corporal Punishment in Schools". Psychiatric Bulletin. 2 (4): 62–64. 1978. doi:10.1192/pb.2.4.62.

- Psychosocial Paediatrics Committee; Canadian Paediatric Society (2004). "Effective discipline for children". Paediatrics & Child Health. 9 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1093/pch/9.1.37. PMC 2719514. PMID 19654979.

- "Legislative assembly questions #0293 - Australian Psychological Society: Punishment and Behaviour Change". Parliament of New South Wales. 20 October 1996. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- "Corporal Punishment". www.nassp.org/. National Association of Secondary School Principals. 13 February 2018.

- "Position Statement: Corporal Punishment". https://www.nasponline.org. National Association of School Psychologists. External link in

|website=(help) - Heisel, Andrew. "'I Don't Know Whether to Kiss You or Spank You': A Half Century of Fear of an Unspanked Woman". Pictorial. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- Snyder-Hall, R. Claire (2008). "The Ideology of Wifely Submission: A Challenge for Feminism?". Politics & Gender. 4 (4): 563–586. doi:10.1017/S1743923X08000482.

- Zadrozny, Brandy (19 June 2013). "Spanking For Jesus: Inside The Unholy World Of 'Christian Domestic Discipline'". The Daily Beast.

- Zadrozny, Brandy (19 June 2013). "Spanking for Jesus: Inside the Unholy World of 'Christian Domestic Discipline'". The Daily Beast.

- Bennett-Smith, Meredith (21 June 2013). "Christian Domestic Discipline Promotes Spanking Wives To Maintain Biblical Marriage". Huffpost.

- "Ring in the new year with a spanking for luck". Independent Online (South Africa). 26 January 2004.

- Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R. (2004). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: men and women in the world's cultures. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. pp. M1 382. ISBN 0-306-47770-X.

- Montley, Patricia (2005). In Nature's Honor: Myths And Rituals Celebrating The Earth. Boston, MA: Skinner House Books. pp. M1 56. ISBN 1-55896-486-X.

- Knab, Sophie Hodorowicz (1993). Polish customs, traditions, and folklore. New York: Hippocrene. ISBN 0-7818-0068-4.

- Walters, Joanna (12 November 2000). "Reach for the top and a birching". The Guardian. London.

External links

| Look up spanking in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |