Battle of Les Avins

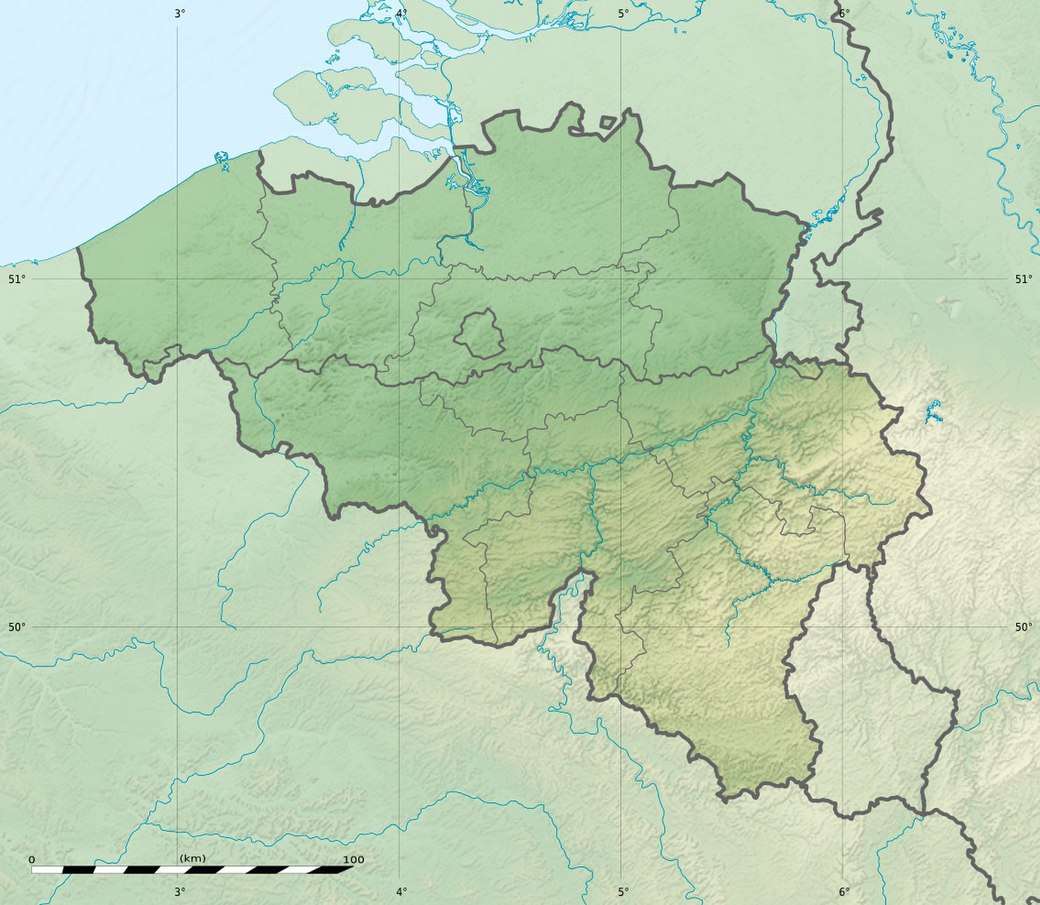

The Battle of Les Avins or Avein took place on 20 May 1635, outside the town of Les Avins, near Huy in modern Belgium, then part of the Bishopric of Liège. It was the first major engagement of the 1635 to 1659 Franco-Spanish War, a subsidiary conflict of the Thirty Years' War.

| Battle of Les Avins | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Franco-Spanish War (1635–59) | |||||||

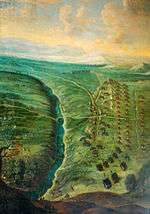

Battle site; Spanish forces at left, French below | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 27,000 | 8,500 – 13,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000 – 2,000 | 4,000 – 5,000 dead, wounded or captured [1] | ||||||

France supported the Dutch Republic in its war of independence from Spain, but avoided direct involvement. In February 1635, the two countries agreed to divide the Spanish Netherlands and in May, a French army of 27,000 entered the Bishopric of Liège, intending to link up with the Dutch at Maastricht and attack Leuven.

Outside Les Avins, they ran into a Spanish force of between 8,500 to 13,000; the French made a frontal assault and over-ran their positions, inflicting around 4,000 – 5,000 casualties, including 1,500 prisoners.

Background

.jpg)

17th century Europe was dominated by the struggle between the Bourbon kings of France, and their Habsburg rivals in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In 1938, historian CV Wedgwood argued the 1618 to 1648 Thirty Years War and the 1568 to 1648 Dutch revolt formed part of a wider, ongoing European struggle, with the Habsburg-Bourbon conflict at its centre. This is generally accepted by modern historians, making the Franco-Spanish War a connected conflicts; understanding this is essential to an appreciation of strategic objectives.[2]

Habsburg territories in the Spanish Netherlands, Franche-Comté, and the Pyrenees blocked French expansion, and made it vulnerable to invasion. Occupied by domestic Huguenot rebellions from 1622 to 1630, France looked for opportunities to weaken the Habsburgs, while avoiding direct conflict.[3]

It included support for the Dutch against Spain, and financing Swedish intervention in the Empire, which began in 1630, when Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden invaded Pomerania. Partly a desire to support his Protestant co-religionists, it also involved control of the Baltic trade, which provided much of Sweden's income.[4]

Economic objectives meant Swedish intervention continued after Gustavus was killed in 1632, but led to conflict with Saxony, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Norway. Defeat at Nördlingen in September 1634 forced the Swedes to retreat, while most of their German allies made peace with Ferdinand in the 1635 Treaty of Prague.[5]

Spain restarted the Dutch War when the Twelve Years' Truce ended in 1621, but by 1633, they were on the retreat again. The powerful Amsterdam mercantile lobby saw an opportunity to end the war. Although negotiations ended without result, the Dutch peace party grew in strength.[6] Concerned by the prospect of the Habsburgs making peace on favourable terms in the Empire and the Netherlands, Louis XIII and his chief minister Richelieu decided on direct intervention. In February 1635, they signed an alliance with the Dutch, agreeing to divide the Spanish Netherlands, and in April, the Treaty of Compiègne with Sweden.[7]

The battle

Much of the fighting focused on different parts of the Spanish Road, an overland supply route connecting Spanish possessions in Northern Italy to Flanders. After 1601, it was rarely used for moving soldiers, but remained vital for trade, and went through areas essential to French security. At the start of 1635, France threatened the Road at a variety of points; as well as 27,000 men under Urbain de Maillé-Brézé in Picardy, they had armies in Champagne, Lorraine, the Sarre, and the Valtellina.[8]

However, the French military was not yet the force it later became, and the 1635 campaign showed serious weaknesses in logistics and co-ordination. With over 100,000 men under arms, they underestimated the effort required to support these numbers, and there was very little co-ordination between the different armies.[9]

In May, Louis declared war on Spain, claiming to be responding to a request for support from the Elector of Trier, whose territories were occupied by Spanish troops. They included the Bishopric of Liège, last point in the Road.[10]

The French entered Liège in two divisions, one led by Maillé-Brézé and the other by Châtillon. Their intention was to link up with Dutch forces based at Maastricht, under the Prince of Orange, and then attack Leuven. Outside Les Avins, they made contact with a Spanish force of between 8,500 to 13,000, commanded by Thomas, Prince of Carignano.[11]

Although inferior in numbers, the Spanish were more experienced and in a strong position, their infantry placed behind a series of hedges, and artillery covering the approaches. The French commanders debated whether to attack, before deciding retreat would be more dangerous. Their artillery commander, Charles de La Porte, positioned his guns to provide covering fire; Châtillon and Maillé-Brézé drew up their troops in standard formation, infantry in the centre and cavalry on the wings, before launching a frontal assault.[11]

On the right, Maillé-Brézé was initially repulsed with heavy losses, before rallying and attacking again. On the left and centre, Châtillon attacked the Spanish artillery with 4,000 men and eventually over-ran their positions by weight of numbers. Seeing this, the French reserve of 5,000 came up; assuming this was a new army, Carignano ordered a general retreat.[12]

Most of the Spanish casualties occurred in this phase of the battle; they lost 4,000 – 5,000 dead, wounded or taken prisoner, including Charles of Austria, nephew of Emperor Ferdinand, and the Comte de Feria. Exact French losses are unknown but they suffered severely in their assault.[12]

Aftermath

News of the victory was received in Paris with elation, and led to unrealistic optimism about the rest of the campaign. It also caused friction between the French commanders, Châtillon claiming he had been sidelined to ensure Maillé-Brézé won the glory.[13]

After linking up with the Dutch, their combined force totalled around 45,000 men, but Fredrick Henry insisted on taking Tienen, a place of limited strategic value. The Cardinal-Infante, governor of the Spanish Netherlands, withdrew to Leuven, leaving a garrison of 1,200 at Tienen. Its capture on 10 June resulted in one of the most serious atrocities of the Dutch Revolt; the town was sacked, over 200 civilians killed and many buildings damaged, including Catholic churches and monasteries. This ended prospects of winning over the predominately Catholic population of the Southern Netherlands, stiffened Spanish resistance, and was particularly embarrassing for Cardinal Richelieu.[14]

Until the advent of railways in the 19th century, water was the primary means of bulk transportation; Leuven's position on the River Dyle made its capture essential for an offensive into Brabant. By the time the Franco-Dutch army began the siege on 24 June, desertion due to lack of food or pay had reduced the French army to under 17,000. When a Spanish force advanced on Leuven in early July, the siege was abandoned; on 28 July, the loss of the Dutch fortress of Schenkenschans prompted Frederick Henry to withdraw from the Spanish Netherlands and march to its relief.[15]

References

- Guthrie 2003, p. 190.

- Sutherland 1992, pp. 588–595.

- Hayden 1973, pp. 1–23.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 385–386.

- Knox 2017, pp. 182–183.

- Israel 1995, pp. 521–523.

- Poot 2013, pp. 120–122.

- Thion 2013, p. 20.

- Wilson 1976, p. 259.

- Forsberg 2016, p. 73.

- De Périni 1896, p. 177.

- De Périni 1896, p. 178.

- Parrott 2001, p. 113.

- Lasaffer 2006, pp. 3–4.

- Asbach & Schröder 2014, pp. 169–170.

Sources

- Asbach, Olaf; Schröder, Peter (2014). The Dutch-French Invasion, 1635–1646 in The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years' War. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409406297.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume III. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forsberg, Anna Maria (2016). Story of War: Church & Propaganda in France & Sweden in 1610–1710. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-9188168665.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guthrie, William (2003). The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32408-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayden, J Michael (1973). "Continuity in the France of Henry IV and Louis XIII: French Foreign Policy, 1598-1615". The Journal of Modern History. 45 (1). JSTOR 1877591.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). Spain in the Low Countries, (1635-1643) in Spain, Europe and the Atlantic: Essays in Honour of John H. Elliott. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521470452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knox, Bill (2017). "The 1635 Treaty of Prague; a failed settlement?". In Tucker, Spencer (ed.). Enduring Controversies in Military History, Volume I: Critical Analyses and Context. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-1440841194.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lasaffer, Randall (2006). "Siege Warfare and the Early Modern Laws of War". Tilburg Working Paper Series on Jurisprudence and Legal History. 06 (01).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parrott, David (2001). Richelieu's Army: War, Government and Society in France, 1624–1642. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521792097.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poot, Anton (2013). Crucial years in Anglo-Dutch relations (1625–1642): the political and diplomatic contacts. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9087043803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sutherland, NM (1992). "The Origins of the Thirty Years War and the Structure of European Politics". English Historical Review. 107 (424).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thion, Stephane (2013). French Armies of the Thirty Years War (Soldiers of the Past). Histoire et Collections. ISBN 978-2917747018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wedgwood, CV (1938). The Thirty Years War (2005 ed.). New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1590171462.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Charles (1976). Transformation of Europe, 1558-1648. Littlehampton Book Services. ISBN 978-0297770152.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)