Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659)

The Franco-Spanish War of 1635 to 1659 was one of a series of wars between France, and their Habsburg rivals in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. It is considered a connected conflict of the 1568 to 1648 Dutch Revolt, and 1618 to 1648 Thirty Years War. Though some minor territorial gains were made by France, the war ended inconclusively in 1659 with the Treaty of the Pyrenees.[5][6][7]

Note; Arbitration Pending

| Franco–Spanish War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rocroi; considered the turning point of the perceived invincibility of the Spanish Tercio on European battlefields | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

c. 100,000 (1640s)[lower-alpha 1] c. 120,000 (1653)[1] c. 110,000–125,000 (1653–1659)[3] | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||||

Major areas of conflict included Northern Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, Catalonia, and the Rhineland. Spain financed French Huguenot rebellions from 1622 to 1630, and the 1648 to 1653 civil war known as the Fronde; France supported revolts against Spanish rule in Portugal, Catalonia and Naples.

While France supported Habsburg opponents in the Dutch Revolt and Thirty Years War, it avoided direct involvement until 1635, when it agreed alliances with the Swedes and Dutch. After these ended in the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, fighting continued between Spain and France, with neither able to gain an advantage.

The 1657 Anglo-French alliance led to an offensive in Flanders, and victory at the June 1658 Battle of the Dunes. This did little to change the overall position, but the Spanish economy was severely impacted by English naval attacks, while France had largely achieved its strategic objectives. By 1659, both sides were financially exhausted and the war was at a stalemate; they agreed peace terms in November 1659.

While minor in extent, French territorial gains were of greater strategic significance, as was the marriage of Louis XIV of France and Maria Theresa of Spain, eldest daughter of Philip IV. Spain remained a great power, with a vast colonial empire, but the war is often seen as marking the decline of its position as the dominant European state.[8]

Strategic Overview

17th century Europe was dominated by the struggle between the Bourbon kings of France, and their Habsburg rivals in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. Until the mid 20th century, the Thirty Years War was primarily seen as a German religious conflict; in 1938, historian CV Wedgwood argued it formed part of a wider, ongoing European struggle, with the Habsburg-Bourbon conflict at its centre. A perspective now generally accepted by historians, its implication is that strategies pursued during the Franco-Spanish War can only be understood in a European context.[9]

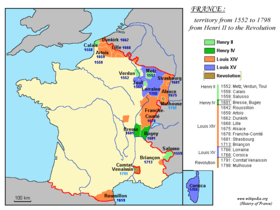

In 1630, Habsburg possessions bordered France in the Spanish Netherlands, Franche-Comté, Alsace, Roussillon and Lorraine (see Map). France supported anti-Spanish wars by the Dutch, and clients in Northern Italy, as well as revolts in Portugal, Catalonia and Naples. French-backed Austrian opponents included the Ottomans, the Venetian Republic, Transylvanian rebels, and Sweden.[10]

Spain and Austria financed Huguenot rebellions in South-Western France, and the 1648 to 1653 civil war known as the Fronde. They also backed conspiracies led by the feudal lords who resented their loss of power under Richelieu and Cardinal Mazarin; the most significant included the 1632 Montmorency plot, the 1641 Princes des Paix rising, and Cinq-Mars in 1642.[11]

Wider co-operation between the Habsburgs was limited, since their objectives did not always align; Spain was a global maritime power, Austria primarily a European land power. The Empire had over 1,800 members, most extremely small; although a Habsburg had been Holy Roman Emperor since 1440, in theory it was an elected position. After 1555, the Empire increasingly became a federation of independent states; encouraged by France, Habsburg acceptance of this reality is one of the less acknowledged outcomes of the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia.[12]

France faced the same issue of diverging objectives with its allies. The war coincided with the period of economic supremacy known as the Dutch Golden Age, and by 1640, many Dutch statesmen viewed French ambitions in the Spanish Netherlands as a threat.[13] Unlike France, Swedish war aims were restricted to Germany, and in 1641, they considered a separate peace with Ferdinand.[14]

Much of the fighting took place around the Spanish Road, an overland supply route connecting Spanish possessions in Northern Italy to Flanders. Rarely used for moving soldiers post-1601, it remained vital for trade, and went through areas like Alsace essential to French security. In Northern Italy, Savoy and the Spanish-held Duchy of Milan were strategically important, since they provided access to the vulnerable southern borders of France, and Habsburg territories in Austria. Richelieu aimed to end Spanish dominance in these areas, an objective largely achieved by the time he died in 1642.[12]

Until the advent of railways in the 19th century, water was the primary means of bulk transportation, and campaigns focused on control of rivers and ports. Armies relied on foraging, while feeding the draught animals essential for transport and cavalry restricted campaigning in the winter. By the 1630s, the countryside had been devastated by years of constant warfare, which limited the size of armies, and the ability to conduct operations. Sickness killed far more soldiers than battle; France invaded Flanders with 27,000 men in May, which was reduced by desertion and disease to under 17,000 in early July.[15]

Background

The Thirty Years War began in 1618 when the Protestant-dominated Bohemian Estates offered the Crown of Bohemia to Frederick of the Palatinate, rather than the conservative Catholic, Emperor Ferdinand II. Most of the Holy Roman Empire remained neutral, viewing it as an inheritance dispute, and the revolt was quickly suppressed. However, when Frederick refused to admit defeat, Imperial forces invaded the Palatinate and forced him into exile; removal of a hereditary prince changed the nature and extent of the war.[16]

Accompanied by a renewed Counter-Reformation, this threatened Protestant states within the Empire. It also drew in external powers who held Imperial territories; Nassau-Dillenburg was a hereditary possession of the Dutch Prince of Orange, while Christian IV of Denmark was also Duke of Holstein. With France facing Spanish-financed Huguenot rebellions from 1622 to 1630, and proxy wars in Italy from 1628 to 1631, this provided opportunities to weaken the Habsburgs, but avoid direct conflict.[17]

France supported the Dutch war with Spain, as well as funding Danish, then Swedish intervention in the Empire. In 1630, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden invaded Pomerania; partly to support his Protestant co-religionists, he also sought control of the Baltic trade, which provided much of Sweden's income.[18] Economic issues meant Swedish intervention continued after Gustavus was killed in 1632, but led to conflict with Saxony, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Norway. Defeat at Nördlingen in September 1634 forced the Swedes to retreat, while most of their German allies made peace with Ferdinand in the 1635 Treaty of Prague.[19]

.jpg)

The other major European conflict of the period was the 1568 to 1648 Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Dutch Republic, suspended in 1609 by the Twelve Years' Truce.[20] The Spanish strongly objected to its commercial provisions and when Philip IV became king in 1621, he resumed the war. The cost proved extremely high, increased after 1628 by a proxy war with France over the Mantuan succession. While the Spanish Empire reached its maximum extent under Philip's rule, its complexity and size made it increasingly difficult to govern, or enact essential reforms.[21]

In 1628, the Dutch captured the Spanish treasure fleet, which they used to finance the 1629 capture of 's-Hertogenbosch. The powerful Amsterdam mercantile lobby saw this as an opportunity to end the war; negotiations ended without result in 1633, but strengthened the peace party.[22] The Peace of Prague led to rumours of a proposed Austro-Spanish offensive in the Netherlands, leading Louis XIII and Richelieu to decide on direct intervention. In early 1635, they signed an agreement with Bernard of Saxe-Weimar to provide 16,000 troops for a campaign in Alsace and the Rhineland, an anti-Spain alliance with the Dutch Republic, and the Treaty of Compiègne with Sweden.[23]

Phase I; 1635 to the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia

In May, a French army of 27,000 advanced into the Spanish Netherlands, defeating a smaller Spanish force at Les Avins, before linking up with the Dutch. Outnumbered, the Cardinal-Infante withdrew into Leuven; by the time the siege began on 24 June, desertions reduced the French to under 17,000, and they withdrew in early July. After the loss of Schenkenschans on 28 July, the Dutch also withdrew from the Spanish Netherlands.[15]

This failure meant the States-General opposed further large scale land operations, and instead prioritised attacks on Spanish trade.[24] In 1636, a Spanish offensive reached Corbie in Northern France; although it caused panic in Paris, lack of supplies forced them to retreat, and it was not repeated. Spain's focus was to recover territories in the Low Countries, and repulse Franco-Savoyard attacks in Lombardy.[25]

As agreed at Compiègne in 1635, the French replaced Swedish garrisons in Alsace; prior to his death in 1639, Bernard of Saxe-Weimar won a series of victories in the Rhineland, the most important being the capture of Breisach in December 1638.[26] This severed the Spanish Road, forcing Spain to reinforce their armies by sea, where the Dutch had maritime supremacy; in 1639, they destroyed a large supply convoy at the Downs. They also attacked Portuguese possessions in Africa and the Americas, then part of the Spanish Empire; Madrid's inability to prevent this caused increasing unrest in Portugal.[27]

Throughout the 1630s, attempts by the Crown of Castile to increase taxes and centralise control led to protests; in 1640, these became revolts in Portugal and Catalonia. In 1641, the Catalan Courts recognised Louis XIII as Count of Barcelona, and ruler of the Principality of Catalonia.[28] However, Catalans found French administration differed little from that of Castile, and the war became a three sided contest between the rural peasantry, the Spanish, and the French and Catalan elite.[29]

On 14 May 1643, Louis XIII died; his five year old son, Louis XIV, became king, his mother, Anne of Austria, taking control of the Regency Council that ruled in his name. Five days later, Condé, then known as the duc d'Enghien, defeated the Spanish Army of Flanders at Rocroi; less decisive than often thought, the loss of this highly experienced unit ended Spanish dominance of the European battlefield.[30] Condé, a member of the royal family, and effective ruler of large parts of eastern France, used it as leverage in his struggle for political control with Anne, and Cardinal Mazarin.[31]

Despite limited success in Northern France and the Spanish Netherlands, including victory at Lens in August 1648, France was unable to knock Spain out of the war. In Germany, Imperial victories at Tuttlingen and Mergentheim were offset by French success at Nördlingen and Zusmarshausen. In Italy, Franco-Savoyard offensives against the Spanish-ruled Duchy of Milan achieved little, partly due to the disruption caused by the 1639 to 1642 Piedmontese Civil War. Victory at Orbetello in June 1646, and the recapture of Naples in 1647 left Spain firmly in control of this region.[32]

The 1648 Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War and recognised Dutch independence, ending the drain on Spanish resources. Under the October 1648 Treaty of Münster, France gained strategic locations in Alsace and Lorraine, as well as Pinerolo, which controlled access to Alpine passes in Northern Italy.[32] However, the peace excluded Italy, Imperial territories in the Low Countries, and French-occupied Lorraine, while Emperor Ferdinand agreed to remain neutral. This meant fighting continued.[33]

Phase II; 1648 to 1659

By 1648, both sides were under increasing financial strain, forcing Philip to prioritise Catalonia, although he nonetheless had to declare bankruptcy in 1647 and 1653.[34] A combination of political conflict and economic stress led to the 1648 to 1653 French civil war known as the Fronde; in 1651, Mazarin forced Condé into exile in the Spanish Netherlands, where he signed an alliance with Philip. He was replaced by Turenne, also a talented commander, but far less powerful politically.[35]

Spain recaptured Barcelona in October 1652, and although fighting continued in Roussillon, by 1653 the front had stabilised along the modern Pyrenees border.[36] After the Fronde ended in 1653, France resumed attempts to capture Milan, which provided access to the vulnerable southern border of Habsburg territories in Austria. Despite support from Savoy, the Duke of Modena and Portugal, they failed to achieve this.[37]

By now, the two antagonists were exhausted, and neither could establish dominance over the other. From 1654 to 1656, French victories at Arras, Landrecies and Saint-Ghislain were offset by Spanish success at Pavia, in Lombardy, and Valenciennes. Under pressure from Pope Alexander VII, Mazarin offered peace terms, but refused to accept Spain's insistence Condé must be restored to his French titles and lands.[38] Philip viewed this as a personal obligation, and with the war apparently going his way, rejected talks.[39]

Prior to the 1660s, France lacked a powerful navy of its own, and instead relied on the Dutch, who ceased to provide this after 1648. Since 1654, Spain had been involved in a naval conflict with the English Commonwealth, and in 1657, Mazarin negotiated an Anglo-French alliance. France was required to end its backing for the exiled Charles II, some of whose supporters joined the Spanish as a result.[40]

1658 featured an Anglo-French offensive in North Flanders, whose main objective was Dunkirk, a centre for Spanish privateer attacks on English shipping.[lower-alpha 2] After the loss of Dunkirk in June, Spain requested a truce, which Mazarin initially refused. However, Cromwell's death led to political chaos in England, while French allies Savoy and Modena ended the war in Northern Italy by agreeing a truce with the Spanish commander, Caracena.[42]

Treaty of the Pyrenees and marriage contract

On 8 May 1659, France and Spain began negotiating terms; the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658 weakened England, which was allowed to observe, but excluded from the talks. Although the Anglo-Spanish War was suspended after the 1660 restoration of Charles II, it did not formally end until the 1667 Treaty of Madrid.[43]

Under the Treaty of the Pyrenees, signed on November 5, 1659, France gained Artois and Hainaut along its border with the Spanish Netherlands, as well as Roussillon, or Northern Catalonia. These were more significant than often assumed; in combination with the 1648 Treaty of Münster, France strengthened its borders in the east and south-west, while in 1662, Charles II sold Dunkirk to France. Acquisition of Roussillon established the Franco-Spanish border along the Pyrenees, but divided the historic Principality of Catalonia, commemorated each year by French Catalan-speakers in Perpignan.[44]

France withdrew support from Afonso VI of Portugal, while Louis XIV renounced his claim to be Count of Barcelona, and king of Catalonia. Condé regained his possessions and titles, as did many of his followers, such as the Comte de Montal, but his political power was broken, and he did not hold military command again until 1667.[45]

An integral part of the peace negotiations was the marriage contract between Louis and Maria Theresa, which he used to justify the 1666 to 1667 War of Devolution, and formed the basis of French claims over the next 50 years. The marriage was more significant than intended, since it was agreed shortly after Philip's second wife, Mariana of Austria, gave birth to a second son, both of whom died young.[46] Philip died in 1665, leaving his four year old son Charles as king, once described as "always on the verge of death, but repeatedly baffling Christendom by continuing to live."[47]

Aftermath and historical assessment

While the war has been retrospectively viewed as the beginning of the decline of Spain, this was not interpreted as such at the time. Although France made crucial strategic gains around its borders, modern assessments suggest that it had a balanced outcome.

"The (1659 treaty) was a peace of equals. Spanish losses were not great, and France returned some territory and strongholds. With hindsight, historians have regarded the treaty as a symbol of the 'decline of Spain' and the 'ascendancy of France'; at that time, however, (it) appeared a far from decisive verdict on the international hierarchy".[48]

"Spain maintained her supremacy in Europe until 1659, and was the greatest imperial power for years after that. Although (its) economic and military power suffered an abrupt decline in the half century after (1659), (it) was a major participant in the European coalitions against Louis XIV, and the peace congresses at Nijmegen in 1678, and Ryswick in 1697".[49]

David Parrott, Professor of Early Modern History at New College, Oxford suggests that both the Peaces of Westphalia and the Pyrenees reflected mutual exhaustion and stalemate, not a military diktat imposed by victorious powers.[50] Elsewhere, he labels the war as "25 years of indecisive, over-ambitious and, on occasions, truly disastrous conflict".[51]

The near equality between the European powers in this period meant the 1635-1659 conflict, like other wars, was inconclusive, Spain and France effectively settling for a draw.[52] Rob Stradling, an expert in Spanish history, and formerly Professor of History at Cardiff University, argues that had France not moderated its demands in 1659, the war would have been continued interminably.[53]

Notes

- The strength of the French Army fluctuated greatly in the 1640s, and estimates by historians vary accordingly, ranging from 218,000 to just 40,000 around 1645–1648.[1] On average, it is likely that about 100,000 soldiers were usually in the field at the time.[2]

- Its location meant ships based in Dunkirk could enter the North Sea on a single flood tide, allowing them to raid as far north as the Orkney Islands; its closure was a British objective for centuries.[41]

References

- Chartrand 2019, p. 33.

- Chartrand 2019, p. 24.

- Chartrand 2019, p. 34.

- Wilson 2009.

- Parrott, David: Richelieu's Army: War, Government and Society in France, 1624–1642. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521792096, pp. 77–78. France's War against Habsburgs, 1624-1659: the Politics of Military Failure in García Hernan, Enrique; Maffi, Davide: Guerra y Sociedad en La Monarquía Hispánica: Politica, Estrategia y Cultura en la Europa Moderna (1500-1700), 2 vols; Madrid: Laberinto, 2006. ISBN 9788400084912, pp. 31-49.

- Darby, Graham: Spain in the Seventeenth Century. London: Longman, 1995. ISBN 9780582072343, p. 66.

- Luard, Evan: War in International Society: A Study in International Sociology. London: Tauris, 1986, p. 50. ISBN 9781850430124. Black, Jeremy: The Origins of War in Early Modern Europe. Edinburgh: J. Donald, 1987, p. 106. ISBN 9780859761680

- Parrott 2001, pp. 77-78.

- Sutherland 1992, pp. 588-590.

- Jensen 1985, pp. 451-470.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 663-664.

- Wilson 1976, p. 259.

- Wilson 2009, p. 669.

- Wilson 2009, p. 627.

- Van Nimwegen 2014, pp. 169-170.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 314-316.

- Hayden 1973, pp. 1-23.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 385-386.

- Knox 2017, pp. 182-183.

- Lynch 1969, p. 42.

- Mackay 1999, pp. 4-5.

- Israel 1995, pp. 521-523.

- Poot 2013, pp. 120-122.

- Israel 1995, p. 934.

- Israel 1995, pp. 272-273.

- Bely 2014, pp. 94-95.

- Costa 2005, p. 4.

- Van Gelderen 2002, p. 284.

- Mitchell 2005, pp. 431-448.

- Black 2002, p. 147.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 666-668.

- Paoletti 2007, pp. 27-28.

- Wilson 2009, p. 747.

- Inglis Jones 1994, pp. 59-64.

- Inglis Jones 1994, pp. 9-12.

- Parker 1972, pp. 221-224.

- Schneid 2012, p. 69.

- Inglis Jones 1994, pp. 296-300.

- Black 1991, p. 16.

- Quainton 1935, p. 268.

- Bromley 1987, p. 233.

- Hanlon 2016, p. 134.

- Davenport & Paullin 1917, p. 50.

- Serra 2008, pp. 82-84.

- Tucker 2011, p. 838.

- Inglis Jones 1994, p. 307.

- Durant & Durant 1963, p. 25.

- Darby 2015, p. 66.

- Levy 1983, p. 34.

- Parrott, 2003 & pp77–78.

- Parrott 2006, pp. 31-49.

- Luard 1986, p. 50.

- Stradling 1994, p. 27.

Sources

- Bely, Lucien (2014). Asbach, Olaf; Schröder, Peter (eds.). France and the Thirty Years War in The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years' War. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409406297.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (2002). European Warfare, 1494-1660 (Warfare and History). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415275316.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (1991). A Military Revolution?: Military Change and European Society, 1550-1800 (Studies in European history). Palgrave. ISBN 978-0333519066.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bromley, JS (1987). Corsairs and Navies, 1600-1760. Continnuum-3PL. ISBN 978-0907628774.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chartrand, René (2019). The Armies and Wars of the Sun King 1643–1715. Volume 1: The Guard of Louis XIV. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-911628-60-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Costa, Fernando Dores (2005). "Interpreting the Portuguese War of Restoration (1641-1668) in a European Context". Journal of Portuguese History. 3 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Darby, Graham (2015). Spain in the Seventeenth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138836440.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davenport, Frances Gardiner; Paullin, Charles Oscar, eds. (1917). European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies, Vol. 2: 1650-1697 (2018 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-0483158924.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Durant, Ariel; Durant, Will (1963). Age of Louis XIV (Story of Civilization). TBS Publishing. ISBN 0207942277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanlon, Gregory (2016). The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560-1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138158276.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayden, J Michael (1973). "Continuity in the France of Henry IV and Louis XIII: French Foreign Policy, 1598-1615". The Journal of Modern History. 45 (1). JSTOR 1877591.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Inglis Jones, James John (1994). The Grand Condé in exile; Power politics in France, Spain and the Spanish Netherlands, 1652-1659. Oxford University Thesis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477-1806. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198730729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). Spain in the Low Countries, (1635-1643) in Spain, Europe and the Atlantic: Essays in Honour of John H. Elliott. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521470452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, De Lamar (1985). "The Ottoman Turks in Sixteenth Century French Diplomacy". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 16 (4).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knox, Bill (2017). Tucker, Spencer (ed.). The 1635 Treaty of Prague; a failed settlement? in Enduring Controversies in Military History, Volume I: Critical Analyses and Context. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-1440841194.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levy, Jack (1983). War in the Modern Great Power System, 1495-1975 (2015 ed.). University of Kentucky. ISBN 081316365X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Luard, Evan (1986). War in International Society: A Study in International Sociology. Tauris. ISBN 978-1850430124.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lynch, Jack (1969). Spain Under the Habsburgs: Vol. 11 Spain and America 1598-1700. Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackay, Ruth (1999). The Limits of Royal Authority: Resistance and Obedience in Seventeenth-Century Castile. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521643436.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Andrew Joseph (2005). Religion, revolt, and creation of regional identity in Catalonia, 1640-1643. Ohio State University PHD.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, Geoffrey (1972). The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road 1567–1659: The Logistics of Spanish Victory and Defeat in the Low Countries' Wars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521084628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parrott, David (2001). Richelieu's Army: War, Government and Society in France, 1624–1642. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521792097.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parrott, David (2006). France's War against the Habsburgs, 1624-1659: the Politics of Military Failure in Guerra y Sociedad en La Monarquía Hispánica: Politica, Estrategia y Cultura en la Europa Moderna (1500-1700). Laberinto. ISBN 978-8400084912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poot, Anton (2013). Crucial years in Anglo-Dutch relations (1625-1642): the political and diplomatic contacts. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9087043803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paoletti, Ciro (2007). A Military History of Italy. Praeger Publishers Inc. ISBN 978-0275985059.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quainton, C Eden (1935). "Colonel Lockhart and the Peace of the Pyrenees". Pacific Historical Review. 4 (3). JSTOR 3633132.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schneid, Frederick C (2012). The Projection and Limitations of Imperial Powers, 1618-1850. Brill. ISBN 978-9004226715.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Serra, Eva (2008). "The Treaty of the Pyrenees, 350 Years Later". Catalan Historical Journal. 1. doi:10.2436/20.1000.01.6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stradling, RA (1994). Spain's Struggle For Europe, 1598-1668. Hambledon Press. ISBN 9781852850890.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sutherland, NM (1992). "The Origins of the Thirty Years War and the Structure of European Politics". English Historical Review. 107 (424).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer C (2011). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Vol. II. ABC-CLIO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Gelderen, Martin (2002). Republicanism and Constitutionalism in Early Modern Europe: A Shared European Heritage Volume I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521802031.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2014). Asbach, Olaf; Schröder, Peter (eds.). The Dutch-Spanish War in the Low Countries 1621-1648 in The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years' War. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409406297.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wedgwood, CV (1938). The Thirty Years War (2005 ed.). New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1590171462.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Charles (1976). Transformation of Europe, 1558-1648. Littlehampton Book Services Ltd. ISBN 978-0297770152.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Peter (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0713995923.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)