Battle of Breitenfeld (1631)

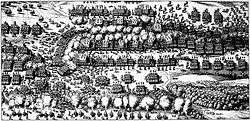

The Battle of Breitenfeld (German: Schlacht bei Breitenfeld; Swedish: Slaget vid Breitenfeld) or First Battle of Breitenfeld (in older texts sometimes known as Battle of Leipzig), was fought at a crossroads near Breitenfeld approximately 8 km north-west of the walled city of Leipzig on September 17 (Gregorian calendar), or September 7 (Julian calendar, in wide use at the time), 1631.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] It was the Protestants' first major victory of the Thirty Years War.

| First Battle of Breitenfeld | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

Gustavus Adolphus at the battle of Breitenfeld, painting by J. Walter, 1632 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Count of Tilly Gottfried zu Pappenheim | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

23,000 Swedes 28,750 men present at Breitenfield[1]

| 35,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,550: 3,550 Swedes dead 2,000 Saxons dead |

27,000: | ||||||

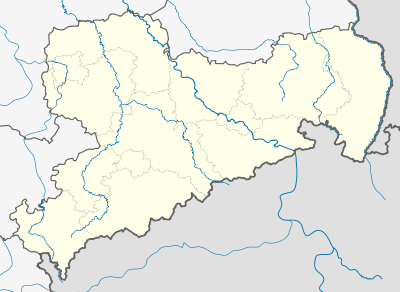

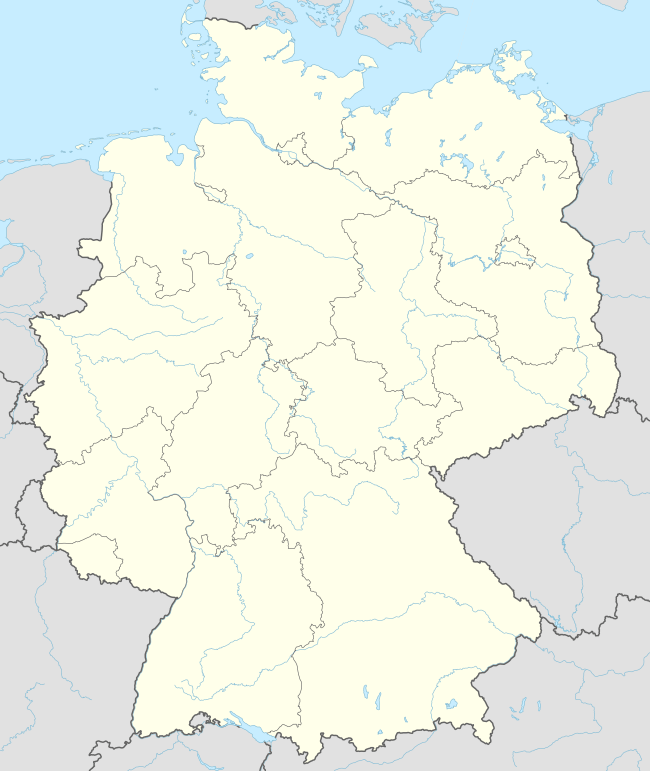

Breitenfeld Location within Saxony  Breitenfeld Breitenfeld (Germany) | |||||||

The victory confirmed Sweden's Gustavus Adolphus of the House of Vasa as a great tactical leader and induced many Protestant German states to ally with Sweden against the German Catholic League, led by Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, and the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II.

Preliminaries

The Swedish phase of the Thirty Years War began when Gustavus Adolphus and his force of 13,000 landed at Peenemünde in 1630. Initially, Sweden's entrance into the war was considered a minor annoyance to the Catholic League and its allies; his only battles to this point had been inconclusive ones, or fought against generals of modest military ability.[2][3]

Consequently, the Imperial Commander of the German Catholic League, Tilly, did not immediately respond to the arrival of the Swedes, being engaged in northern Italy.[4] However, the effective end of the Mantuan War in 1631 ensured that the large Imperial army previously tied up there was now free to move into the German states.[2][3]

Creating alliances

When the Protestant princes showed little interest in attaching themselves to the Swedish cause, Gustavus opted for “rough wooing.”[5] His troops moved south into Brandenburg, taking and sacking the towns of Küstrin and Frankfurt an der Oder. It was too late and too far to save one of Gustav's “occupied” allies, Magdeburg, from a horrific sack by Imperial troops, beginning on May 20, in which a major portion of the population was murdered and the city burned. The Swedes turned the sack of Magdeburg to good use: broadsides and pamphlets distributed throughout Europe ensured that prince and pauper alike understood how the Emperor, or at least his troops, treated his Protestant subjects.[6][7]

Over the next few months, Gustavus consolidated his bridgehead and expanded across northern Germany, attracting support from German princes and building his army from mercenary forces along the way. By the time he reached the Saxon border, his force had grown to over 23,000 men.

Strategic importance of Saxony

In order for Swedes to attack the Imperial troops in the south, they needed to pass through Saxony. In order for Tilly's forces to attack Gustav's army, they too needed to pass through Saxony. The Electorate of Saxony had not been affected by war and had large quantities of resources that each army could utilise. In midsummer, General Tilly asked John George I for permission to pass through the territory; the elector declined permission, noting that Saxony had not been ravaged by war yet. Later Tilly invaded the Electorate of Saxony due to the fact that it was the shortest distance between his army and Gustav's and it possibly annulled the chance of a potential alliance between Saxony and the Imperials.[4][8]

His plan was to avoid contact with the Swedes, and ultimately the Saxons, until his troops could unite with the units near Jena (about 5,000 seasoned professionals), and the larger force of Count Otto von Fugger, en route from Hesse.[8] Gustav and John George united their forces, planning to meet Tilly somewhere near Leipzig.

Tactical overview

The battle was overall a meeting engagement with both combatants agreeing to battle on the field. The forces all had different structural organization. The level of technology was roughly equivalent, with newer, lighter cannon and matchlocks giving the Swedes a slight advantage. Both armies were well supplied, and the terrain gave neither a distinct advantage.

Forces deployed

The forces deployed were roughly equal in strength with the Swedes being slightly outnumbered. The Protestant coalition fielded about 42,000 troops (18,000 of them German), and the Imperial army about 35,000. The Protestants had a considerable edge in cavalry numbers, about 13,000 (5,000 from Allies) to 9,000. Strength of heavy artillery was comparable, with the Swedes having a slight edge in quality and Imperial forces a marginal advantage in quantity. The Swedes had additional small artillery pieces (3 and 6 pounders) integrated into their infantry brigades and regiments, giving them a larger number of tubes overall and a huge firepower advantage in an infantry clash.

The Imperials had a considerable advantage in the number of trained infantry deployed, about 25,000 to the Swedes 15,000. The Saxons (Swedish allies) fielded about 9,000 untrained conscripts and militiamen, and had very few muskets. The Swedish brigade had more muskets and fewer pikemen than the Imperial tercios (who still retained large numbers of lighter firearms known as the arquebus or caliver); overall, the Protestants fielded about the same number of muskets as Imperial troops.

Force assessment

The overall balance was relatively even. The disparity in overall numbers resulted from large levies of untrained soldiers. The number of heavy cannon was relatively close, with the Swedish having newer models and light cannon compensating for the disparity in heavy field pieces. The Swedes had a considerable advantage in cavalry numbers, although the Imperialist cavalry were better armored and better mounted. This balance would be tilted however by the Swedish practice of supporting their cavalry with detachment of musketeers.

Tilly also had a considerable numerical advantage in the number of veteran, trained infantry. Gustavus had a considerable advantage in his artillery arm; he had moved away from heavy siege artillery into more mobile field pieces, which because of its mobility and rate of fire were pound by pound much more effective than the latter. The Swedes also fielded considerably more powerful muskets by ratio, had far more advanced equipment, and better drills to increase their rate of fire. More important, the Linear Formation [9] allowed most Swedish musketeers to fire at the same time, and allowed the Swedish infantry to match the Imperialist frontage with a smaller number of men, which would be crucial in the later phase of the battle. Finally, the Swedish aggressive assault method of firing by triple-ranked salvos at point blank range, compared to the Imperialist's more traditional way of firing by volley would prove to be a nasty shock to Tilly's tercios.

Disposition of forces

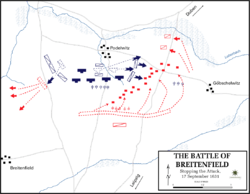

Swedish-Saxon forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

The Swedes deployed their 15,000 infantry in brigades and two lines. The imperial army deployed 25,500 infantry in a single line of 17 tercios (1,500 infantrymen in each). The German allies extended the Swedish-Saxon front to be overall slightly longer than the Imperial. The imperial line had its cavalry evenly distributed on its flanks. The Swedes had their cavalry weighted to their right. The Saxon allies fielded their infantry in wedge formation with units in squares, and cavalry on their flanks. With their Saxon allies extending the Swedes' line, the Protestants had cavalry at the centre and their flanks.

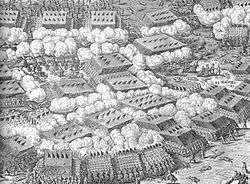

Battle

The battle started in the middle of the day and lasted over six hours. The first two hours consisted of an exchange of artillery fire. This was followed by an Imperial attack with cavalry from both wings to both ends of the Protestant line. The cavalry attack routed the Saxon troops on the Swedish left flank. The Imperial army then conducted a general attack to exploit the exposed left flank. The Swedes repositioned their second line to cover the left flank and counterattacked with their cavalry to both imperial flanks.

The attack on the Imperial left was led personally by Gustavus Adolphus, capturing the Imperial artillery and enveloping the Imperial left flank. The Swedes now had much greater weight of fire from their artillery, infantry, and the captured Imperial artillery. The Imperial line became disorganized under the heavy fire and was enveloped. The Imperial line collapsed and over 80% of Imperial forces were killed or captured.

Opening moves

Swedish-Saxon forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

The combined Swedish-Saxon forces were to the north of Leipzig centred around hamlet of Podelwitz, facing southwest toward Breitenfeld and Leipzig. The battle began around mid-day, with a two-hour exchange of artillery fire, during which the Swedes demonstrated firepower in a rate of fire of three to five volleys to one Imperial volley.[10] Gustavus had lightened his artillery park, and each colonel had four highly mobile, rapid firing, bronze-cast three pounders, the cream of Sweden's metallurgical industry.[11] When the artillery fire ceased, Pappenheim's Black Cuirassiers charged without orders from Tilly, attempting to turn the Swedish right. Instead, their attack fell between Johan Banér's line and the Swedish reserves.[12] They attacked six times to little effect;[13] the small companies of musketeers dispersed between the squadrons of Swedish horse fired salvos at point blank range, disrupting the charge of the Imperialist cuirassier and allowing the Swedish cavalry to counterattack at an advantage. The same tactics worked an hour or so later when the Imperial cavalry charged the Swedish left flank. Following the rebuff of the seventh assault, General Banér sallied forth with both his light (Finnish and West Gaetlanders) and heavy cavalry (Smalanders and East Gaetlanders), forcing Pappenheim and his cavalry to quit the field in disarray, retreating 15 miles northwest to Halle.

During the charges of the Imperialist cuirassiers, Tilly's infantry had remained stationary, but then the cavalry on his right charged the Saxon cavalry and routed it towards Eilenburg. There may have been confusion in the Imperial command at seeing Pappenheim's charge; in their assessment of the battle, military historians have wondered if Pappenheim precipitated an attempted double envelopment, or if he followed Tilly's preconceived plan.[14] At any rate, recognizing an opportunity, Tilly sent the majority of his infantry against the remaining Saxon forces in an oblique march diagonally across his front.

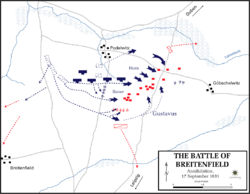

Swedish forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

Swedish forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

Thwarting the Imperial attack

Tilly ordered his infantry to march ahead diagonally to the right, concentrating his forces on the weaker Saxon flank. The entire Saxon force was routed, leaving the Swedish left flank exposed. Before the Imperial forces could regroup and change face towards the Swedes, the commander of the Swedish Left, Marshal Gustav Horn, refused his line and counter-attacked before the tercios could regroup and change face.[15]

The Imperialist tercios then faced the full brunt of the new Swedish firepower for the first time:

"...[Tilly] received a horrible, uninterrupted pounding from the king's light pieces and was prevented from coming to grips with the latter's forces." – Raimondo Montecuccoli, Imperial officer. [16]

"First (saith he), giving fire unto three little Field-pieces that I had before me, I suffered not my muskettiers to give their volleyes till I came within Pistollshot of the enemy, at which time I gave order to the first rancks to discharge at once, and after them the other three: which done we fell pell mell into their ranckes, knocking them downe with the stocke of the Musket and our swords." – Lt. Colonel Muschamp[17]

Annihilation of the Imperial force

With the Imperial forces engaged, the Swedish right and centre pivoted on the refused angle, bringing them in line with Horn. Banér's cavalry, under the direct command of Gustavus Adolphus, attacked across the former front to strike the Imperial left and capture their artillery. As Tilly's men came under fire from their own captured batteries, the Swedish cannon, under Lennart Torstensson, rotated, catching the tercios in a crossfire.[18]

After several hours of punishment, nearing sunset, the Catholic line finally broke. Tilly and Pappenheim were both wounded, though they escaped. 7,600 Imperial soldiers were killed, and 6,000 were captured. The Saxon artillery was recaptured, along with all the Imperial guns and 120 regimental flags.[19]

Aftermath

The outcome of the battle had a significant impact in both the short and long terms.

Short-term effect

In the short term, the Catholic and Imperial forces were significantly hampered by the loss of most of the force. One hundred and twenty standards of the Imperial and Bavarian armies were taken (and are still on display in the Riddarholm church in Stockholm).[14] After the battle, Gustavus moved on Halle, following the same track that Tilly had taken coming east to enforce the Edict of Restitution on the Electorate of Saxony. Two days later Gustav's forces captured another 3,000 men after a brief skirmish at Merseburg, and took Halle two days after that.

After the battle, the Catholic League or Imperial army under Tilly could field an army of only 7,000 men. The army had to be rebuilt. Gustavus Adolphus, on the other hand, had a larger army after the battle than before. The battle's outcome had the political effect of convincing Protestant German states to join his cause. Finally, with the seventy-two-year-old Tilly's recovery far from certain (and he did indeed die within six months while crossing the Lech river), and with no alternative commander at hand, Emperor Ferdinand II had no choice but to rehire Wallenstein.

Long-term consequences

The totality of the victory confirmed Gustav's military innovations and guaranteed that the Swedes would remain engaged in the war for the foreseeable future. In the long term, the significant loss of forces and the creation of a strong Protestant anti-Imperial force required the Emperor and the Protestant and Catholic princes to rethink on the operational conduct of the war, and the diplomatic avenues they would pursue with it.

Gustav's success encouraged several other princes to join the cause of the Swedish king and his few allies. By the month's end, Hanover, the Hessian dukes, Brandenburg and Saxony were officially aligned against the empire, and France had agreed to provide substantially greater funding for Gustavus' armies. Although Gustavus was killed a year later at the Battle of Lützen, the military strength of the alliance had been secured through the addition of new armies. Even when Swedish leadership faltered it did not fail, and the influx of French gold ensured that the hostilities could continue.[20]

Battlefield today

The battlefield today is bisected by the A14 autobahn, which slices through the fields where the majority of the action occurred, between the original position of Tilly, at Breitenfeld, and the original positions of the Swedes and Saxons, around Podelwitz.

In the eastern portion of the village of Breitenfeld stands a monument to Gustav Adolf and the victory his army accomplished there in 1631. It was erected in 1831 on the two hundredth anniversary of the battle and bears the following inscription:

Glaubensfreiheit für die Welt, |

Freedom of belief for the world, |

See also

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Breitenfeld. |

- Breitenfeld (1631) order of battle

- Hakkapeliitta

- Björneborgarnas marsch

Notes

- September 7 (old style or pre-acceptance of the Gregorian calendar in the Protestant region) September 17 (new style, or Gregorian dating), 1631.

- The battle was fought at the crossroads villages of Breitenfeld 51°24′N 12°20′E, Podelwitz 51°24′N 12°23′E, and Seehausen 51°24′N 12°25′E

References

- Mankell 1861.

- Parker 1997, pp. 111–113.

- Meade 1976, pp. 13–16.

- Parker 1997, p. 130.

- Parker 1997, p. 112.

- Parker 1997, p. 110.

- Meade 1976, p. 14.

- Meade 1976, p. 174.

- Jones 2001, p. 245.

- Jones 2001, p. 235.

- Meade 1976, p. 175.

- Tucker 2010, p. 194.

- Davis 2013, p. 292.

- Meade 1976, p. 179.

- Davis 2013, p. 292-293.

- Barker 1975, p. 141.

- Roberts 2010, p. 18.

- Dodge 2012.

- Davis 2013, p. 294.

- Parker 1997, Chapter Conclusion.

Bibliography

- Barker, Thomas (1975). The Military Intellectual and Battle. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780873952514.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Paul (2013). Masters of the Battlefield: Great Commanders from the Classical Age to the Napoleonic Era. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195342352.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodge, Theodore A (2012). Gustavus Adolphus: A History of the Art of War from Its Revival After the Middle Ages to the End of the Spanish Succession War. Kirkland: Tales End Press. ASIN B0092XQLHM.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doughty, Robert A. (1996). Warfare in the Western World: Military Operations from 1600 to 1871. Lexington, Mass: D.C. Heath. ISBN 0-669-20939-2. Retrieved 2011-01-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Archer (1987). The Art of War in the Western World. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-252-01380-8. Retrieved 2011-01-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Archer (2001). The Art of War in the Western World. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06966-8. Retrieved 2011-01-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mankell, Julius (1861). Arkiv till Upplysning om Svenska Krigens och Krigsinstrattningarnes Historia: Tidskiftet 1630-1632 (in Swedish). Vol. 3. Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt & Sons. OCLC 938368423 – via archived PDF file from cgsc.edu.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meade, James Edward (1976). Principles of Political Economy: Just Economy. Vol. 4. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-205-7. Retrieved 2011-01-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, Geoffrey (1997). The Thirty Years' War (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12883-8. Retrieved 2011-01-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Preston, Richard A.; et al. (1991) [1956]. Men in arms: A history of warfare and its interrelationships with Western society (5th ed.). Fort Worth, KS: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030334283.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Keith (2010). Pike and Shot Tactics, 1590–1660. Osprey. ISBN 9781846034695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer (2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598844290.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wedgwood, C.V. (1995) [1938]. The Thirty Years War. New York: Book of the Month Club. OCLC 935482413.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)