Arbëresh language

Arbëresh (also known as Arbërisht, Arbërishtja or T'arbrisht) is the Albanian speech spoken by the Arbëreshë people in Italy, as well as the endonym of the Arvanitic language spoken by Arvanites in Greece.

| Arbëresh | |

|---|---|

| arbërisht | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ˌaɾbəˈɾiʃt] |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Sicily |

| Ethnicity | Arbëreshë |

Native speakers | 100,000 (2007)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin, formerly also Greek[1] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | aae |

| Glottolog | arbe1236[2] |

| Linguasphere | 55-AAA-ah |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

| Atheism · Irreligion · Christianity (Catholicism · Orthodoxy · Protestantism) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka dialect · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Calabria Arbëresh · Cham · Lab) |

| History of Albania |

History

Between the 11th and 14th centuries, Albanian-speaking mercenaries, from the areas that are now Albania and Greece, were often recruited by the Franks, Catalans, Italians and Byzantines.

The invasion of the Balkans by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century caused large waves of emigration from the Balkans to southern Italy. In 1448, the King of Naples, Alfonso V of Aragon, asked the Albanian noble Skanderbeg to transfer to his service ethnic Albanian mercenaries. Led by Demetrio Reres and his two sons, these men and their families were settled in twelve villages in the Catanzaro area of Calabria. The following year, some of their relatives and other Albanians were settled in four villages in Sicily.[3] In 1459 Ferdinand I of Naples also requested assistance from Skanderbeg. After victories in two battles, a second contingent of Albanians was rewarded with land east of Taranto, in Apulia, where they founded 15 villages.[4] After the death of Skanderbeg (1468), resistance to the Ottomans in Albania came to an end. Subsequently, many Albanians fled to neighbouring countries and some settled in villages in Calabria.

There was a constant flow of ethnic Albanians into Italy into the 16th century, and other Albanian villages were formed on Italian soil.[5] The new immigrants often took up work as mercenaries with Italian armies. For instance, between 1500 and 1534, Albanians from central Greece were employed as mercenaries by Venice, to evacuate its colonies in the Peloponnese, as the Turks invaded. Afterwards these troops reinforce defences in southern Italy against the threat of Turkish invasion. They established self-contained communities, which enabled their distinct language and culture to flourish. Arbëreshë, as they became known, were often soldiers for the Kingdom of Naples and the Republic of Venice, between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Despite an Arbëreshë cultural and artistic revival in the 19th century, emigration from southern Italy significantly reduced the population. In particular, migration to the Americas between 1900 and 1940 caused the total depopulation of approximately half of the Arbëreshë villages.

Classification

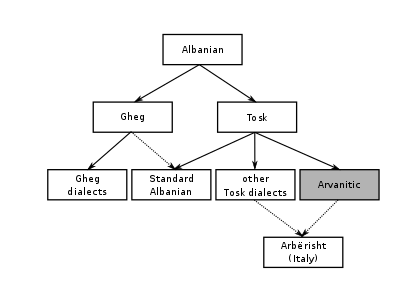

Arbëresh derives from a medieval variety of Tosk, which was spoken in southern Albania and from which the modern Tosk is also derived. It follows a similar evolutionary pattern to Arvanitika, a similar language spoken in Greece. Arbëresh is spoken in Southern Italy in the regions of Abruzzi, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Apulia and Sicily. All the varieties of Arberesh are closely related to each other but are not always entirely mutually intelligible.

Arbëresh retains many features of medieval Albanian from the time before the Ottoman invasion of Albania in the 15th century. It also retains some Greek elements, including vocabulary and pronunciation, most of which it shares with its relative Arvanitika. Many of the conservative features of Arberesh were lost in mainstream Albanian Tosk. For example, it has preserved certain syllable-initial consonant clusters which have been simplified in Standard Albanian (cf. Arbëresh gluhë /ˈɡluxə/ ('language/tongue'), vs. Standard Albanian gjuhë /ˈɟuhə/). Arbëresh most resembles the dialect of Albanian spoken in the south-central region of Albania, and also that of Çam Albanians.

Arbëresh was commonly called 'Albanese' ("Albanian" in the Italian language) in Italy until the 1990s. Arbëresh speakers used to have only very vague notions about how related or unrelated their language was to Albanian. Until the 1980s Arbëresh was exclusively a spoken language, except for its written form used in the Italo-Albanian Byzantine Church, and Arbëreshë people had no practical connection with the Standard Albanian language used in Albania, as they did not use this form in writing or in media. When a large number of immigrants from Albania began to enter Italy in the 1990s and came into contact with local Arbëreshë communities, the differences and similarities were for the first time made apparent. The Arbëreshë have mixed feelings towards the "new Albanians".[6]

Since the 1980s, some efforts have been organized to preserve the cultural and linguistic heritage of the language.

Arbëresh has been replaced by local Romance languages and by Italian in several villages, and in others is experiencing contact induced language shift. Many scholars have produced language learning materials for communities, including those by Zef Skirò Di Maxho who has written two books 'Udha e Mbarë' and 'Udhëtimi', both used in schools in the village of Piana degli Albanesi, Sicily, Gaetano Gerbino wrote Fjalori Arbëresh (Arberesh dictionary), others include Giuseppe Schirò Di Modica, Matteo Mandalà, Zef Chiaramonte, and the only book written in English for the U.S. and U.K. Arberesh diaspora is ‘Everyday Arberesh’ by Martin H. Di Maggio (2013).

False friends

While the relation between Arbëresh and standard Albanian is close, the two are not 100% mutually intelligible and there are many false friends, for example:

| Arbëresh | Meaning | Albanian | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| shërbenj | to work | shërbej | to serve |

| pënonj | to work in the fields | punoj | to work |

| shesh | plateau | shesh | square |

| kopíl | young man | kopil | bastard |

| brekë | trousers | brekë | underpants |

| brumë | pasta | brumë | dough |

| zienj | to cook | ziej | to boil |

Varieties

The varieties of Arberisht largely correspond with the regions where they are spoken, while some settlements have distinctive features that result in greater or lesser degrees of mutual intelligibility.

The Siculo-Arbëresh variety is spoken exclusively in the Province of Palermo and in three villages; Piana degli Albanesi, Santa Cristina Gela and Contessa Entellina, while the varieties of Piana and Santa Cristina Gela are similar enough to be entirely mutually intelligible, the variety of Contessa Entellina is not entirely intelligible. Therefore a further dialect within Siculo-Arberesh known as the Palermitan-Arberisht variety can be identified,[7] as well as a Cosenza variety, a Basilicata variety, a Campania variety represented by the speech of one single settlement of Greci. There is also a Molisan-Arbëresh and an Apulio-Arbëresh.

Within the Cosenza Calabrian varieties of Arbëresh, the dialect of Vaccarizzo Albanese is particularly distinct. Spoken in the villages of Vaccarizzo Albanese and San Giorgio Albanese in Calabria by approximately 3,000 people. Vaccarizzo Albanian has retained many archaic features of both Gheg and Tosk dialects.

Phonology

Some features of Arbërish distinguish it considerably from standard Albanian. In some cases these are retentions of older pronunciations.

Vowels

- Ë

The letter ⟨Ë⟩ is pronounced as either a mid central vowel [ə] or as a close back unrounded vowel [ɯ]. So the word Arbëresh is pronounced either [ɑɾbəˈɾɛʃ] or [ɑɾbɯˈɾɛʃ] depending on the dialect.

- Y to I

Arbërisht lacks the close front rounded vowel [y] of Albanian, which is replaced by the close front unrounded vowel [i]. For example ty ('you') becomes ti, and hyni ('enter') becomes hini.

Consonants

GJ, Q

The letters ⟨GJ⟩ and ⟨Q⟩ are pronounced as a palatalized voiced velar plosive [ɡʲ] and a palatalized voiceless velar plosive [kʲ], rather than a voiced palatal plosive [ɟ] and a voiceless palatal plosive [c] as in standard Albanian. E.g. the word gjith ('all') is pronounced [ɡʲiθ] rather than [ɟiθ], qiell ('heaven') is pronounced [kʲiɛx] rather than [ciɛɫ], and shqip ('albanian') is pronounced [ʃkʲɪp].

GL, KL

In some words, Arbëresh has preserved the consonant clusters /ɡl/ and /kl/. In Standard Albanian these have mostly become the palatal stops gj and q. E.g. glet not gjet ('s/he looks like ... '), klumësht not qumësht ('milk'), and klisha instead of kisha ('church').

H, HJ

The letter ⟨H⟩ is pronounced as a voiceless velar fricative [x] (a sound also found in Greek: χαρά [xaˈra], 'joy'). As such, the Albanian word ha ('eat') is pronounced [xɑ], not [hɑ]. Arbëresh additionally has the palatalized counterpart, [ç]. Therefore, the word hjedh ('throw') is pronounced [çɛθ]. The letter combination ⟨HJ⟩ is present in a few standard Albanian words (without a voiceless velar fricative), but is not treated as a separate letter of the alphabet as it is in Arbëresh.

LL, G

The letters ⟨LL⟩ and ⟨G⟩ are realised as a voiced velar fricative [ɣ] (also found in Greek: γάλα [ˈɣala], 'milk'). The vast majority of these words originate in Sicilian, but the sound also occurs in words of Albanian origin. Often ⟨G⟩ is replaced by ⟨GH⟩ in the Arbëresh orthography. This feature is very strong that it is carried over into the Italian speech of inhabitants of Piana degli Albanesi and Santa Cristina Gela in words such as Grazie, Frigorifero, Gallera, Magro, Gamba etc. which are realised respectively as [ʁratsiɛ], [friɣoˈrifero], [ɣaˈlɛra], [ˈmaɣro], [ˈʁamba] etc.[8][9] In Piana degli Albanesi the tendency is to treat Italian loanwords differently from Sicilian, which results in the difference between llampjun, pronounced as [ʁampˈjun] (from lampione, 'lamp post'), and lampadhin, pronounced as [lampaˈðin] (from Italian lampadina). In the first example, the ⟨L⟩ becomes ⟨LL⟩ [ʁ] because it comes from Sicilian, whereas in the process of transference from the Italian ampadina to Arbëresh lampadhin, the ⟨l⟩ does not change but the ⟨d⟩ becomes [ð].

| Written | Pronounced | English |

|---|---|---|

| gëzim (gioia) | [ʁzim] | joy |

| gajdhur (asino) | [ɣajˈður] | donkey |

| grish (invitare) | [ʁriʃ] | invite |

| llah | [ɣaχ] | eat until stuffed |

| pagëzim (battesimo) | [paʁˈzim] | baptism |

| rruga (la strada) | [ˈruɣa] | street |

| Written | Pronounced |

|---|---|

| fugurë | [fuɣurə] |

| fugatjar | [fuɣatˈjar] |

| garazh | [ɣarˈaʒ] |

| gurg | [ɣurɣ] |

| gust | [ɣust] |

| guant | [ɣwant] |

| magare | [maɣaˈri] |

Final devoicing of consonants

In contrast with standard Albanian Arbëresh has retained an archaic system of final devoicing of consonants. The consonants that change when in final position or before another consonant are the voiced stops b, d, g, gj; the voiced affricates x, xh; and the voiced fricatives dh, ll, v, z, zh.

| Original voiced | b [b] | d [d] | g [ɡ]/[ɣ] | gj [ɡʲ] | x [dz] | xh [dʒ] | dh [ð] | ll [ɣ] | v [v] | z [z] | zh [ʒ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devoiced | p [p] | t [t] | k [k] | q [kʲ] | c [ts] | ch [tʃ] | th [θ] | h [x] | f [f] | s [s] | sh [ʃ] |

Examples:

- b > p: thelb ('clove') - [θɛlp]

- d > t: vend ('place') - [vɛnt]

- dh > th: zgledh ('read') - [sklɛθ]

- g > k: lig ('bad') - [lɪk]

- gj > q: zogj ('chicks') - [zɔkʲ]

- j > hj: vaj ('oil') - [vaç]

- ll > h: uthull ('vinegar') - [ʊθʊχ]

- x > c: ndanx ('near') - [ndant͡s]

- z > s: loz ('dance') - [lɔs]

- zh > sh: gozhda ('pin') - [ɣɔʃda]

Stress

Stress in Arbëresh is usually on the penultimate syllable, as in Italian.

Morphology

In Arbëresh the first person present indicative (e.g. "I work") is marked by the word ending in NJ, whereas in Albanian this is normally marked by J. So, 'I live' is rrónj in Arbëresh and rroj in standard Albanian. The present continuous or gerund differs from Standard Albanian; Arbëresh uses the form "jam'e bënj" instead of "po bej" (I am doing).

Non-Albanian derived elements

Vocabulary

Some Arbëresh words appear to be of Greek origin.

Examples:

From Greek:

- amáhj [aˈmaç] ('war') < μάχη [ˈmaçi] ('battle').

- haristís [xaɾiˈstis] ('thank') < ευχαριστώ [e̞fˌxariˈsto̞] ('thank you'). Arvanitika uses fharistisem.

- hora [xɔˈɾə] ('village') < χώρα [chóra] ('land, village')

- parkalés [paɾkaˈlɛs] ('I plead', 'please') from Greek παρακαλώ [paˌrakaˈlo̞] ('please').

- hiravol (sheaf, a bundle of harvested crop), < χειρόβολο (χειρ = hand).

- dhomat (bundle, pack), < Gr. δεμάτιον.

- argomē (fallow, plowing), < όργωμα. Today surviving in the toponym Argomazit of Piana dei Albanesi.

- kalogreshza (little woman monk), < καλόγρια = woman monk.

- gjitonia (neighbourhood), < γειτονία.

- dhaskal (teacher), < δάσκαλος.

- akoma (still [adverb]), < ακόμα.

On the Greek elements in the Italo-Albanian dialects see T. Jochalas (1975).[10]

Archaic Sicilianisms

Alongside the Greek component in Arbëresh, there is an extensive vocabulary derived from Sicilian and other southern Italian regional languages. Many of these words have retained their original meanings where Sicilian has given way to Italian in everyday speech amongst the non-Arbëresh Sicilian people.

Examples:

- ghranët ('money') < Sic. granna, meaning 'grains'. It is still used in some contexts by modern Sicilian speakers, but in all situations in Arbëresh. Another Arbëresh word for 'money' is haromë, but is no longer used.

- qaca ('square') < Sic. chiazza; used in all Arbëresh dialects as well as Sicilian. The Albanian word sheshi which means 'square' in standard Albanian means 'plateau' in Arbëresh.

- rritrenjët ('toilets') < Norman French via Sic. retained in Arbëresh, but no longer in use in modern Sicilian.

- rritëratë ('photograph') < Sic. 'picture' (ritrattu), more common in Arbëresh than in modern Sicilian.

- zdar (to go to the countryside) < Sic. sdari; no longer commonly used in Sicilian.

- zgarrar (to make a mistake; to err) < Sic. sgarrari (now carries a different meaning in Sicilian).

Incorporation

Alongside the Sicilian vocabulary element in Siculo-Arbëresh, the language also includes grammatical rules for the incorporation of Sicilian-derived verbs in Arbëresh, which differs from the rules concerning Albanian lexical material.

Examples:

- pincar ('think'), originally mendonj-mbanj mend but also mëndinj; derived from the Sicilian 'pinzari'. Which conjugates in the present tense as follows:

- U pincar = I think

- Ti pincar = You think

- Ai/Ajo pincar = He/She thinks

- Na pincarjëm = We think

- Ata/Ato pincarjën = They think

- Ju pincarni = You (pl) think

In the past tense this conjugates as follows:

- U pincarta = I thought

- Ti pincarte = You thought

- Ai/Ajo pincarti = He/She thought

- Na pircartëm = We thought

- Ata/Ato pincartën = They thought

- Ju pincartët = You (pl.) thought

Contractions

| M’e tha mua | He told me (feminine object) |

| Ngë m’i tha më | He did not tell me (masculine object) |

| T’e thom | I tell you (feminine object) |

| T’i thom | I tell you (masculine object) |

Diminutives and augmentatives

The Arbëresh diminutive and augmentative system is calqued from Sicilian and takes the form of /-ats(-ɛ)/ = Sic. -azz(u/a); for example "kalac" (cavallone/big horse), and the diminutive takes the form of /-tʃ-ɛl(-ɛ) from Sic. /-c-edd(u/a); for example "vajziçele" (raggazzina/little girl).The Arbëresh word for "swear word" is "fjalac" and comes from a fusion of the Arbëresh word of Albanian etymology: "fjalë" plus the Sicilian augmentative /-azz[a]/ minus the feminine gendered ending /-a/; this calques the Sicilian word 'palurazza' which is cognate with Italian 'parolaccia'.[9]

Comparison with other forms of Albanian

There are many instances in which Arberisht differs greatly from Standard Albanian, for instance:

| Arbërisht | Shqip (Standard Albanian) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Vje' më rarë or vje' më thënë | do të thotë or do me thënë | It means |

| Bëjëm të shkonj (Piana degli Albanesi) or mënd e më shkosh (Santa Cristina) | më le të kaloj | Let me pass |

| Shkòmë musturën | më jep piperin | Pass me the pepper |

| Zotërote/Strote ë një "zot"? | Zotëri, jeni prift? | Sir, are you a priest? |

| E ghrish zotërisë satë për një pasijatë | ju ftoj për një shëtitje | I invite you for a stroll |

| Zglith mirë | lexo mirë | Read well |

| Qëroi isht burinë i lig | moti është shumë keq | The weather is very bad |

| U rri Sëndahstinë | jetoj në Shën Kristinë | I live in Santa Cristina |

| Ka bëjëm të ngrënit | do ta gatuajmë ushqimin | We will prepare the food |

| U ka' jecur njera qacës | unë kam ecur deri sheshit | I have walked to the square |

| Ghajdhuri isht ghrishur ndë horën | gomari është ftuar në katund | The donkey is invited into the village |

| Jam e vete/m'e vete ngulem/flë | unë do të fle | I'm going to sleep |

| Lyp (lip) ndjesë se zgarrarta shumë | më fal se gabova shumë | I'm sorry that I've made so many errors |

| Ajo isht time shoqe | ajo është gruaja ime | She is my wife |

| Flit t'arbrisht | fol shqip | Speak Albanian! |

| Jim shoq isht e ngulet | shoku im është duke fjetur | My husband is sleeping |

| Më përqen rritëratën tënë | më pëlqen fotografia jonë | I like our photograph |

| Mortatë or motrëmëmë | hallë or tezë | Aunt |

| Lalë or vovi | xhaxha or Lalë (dialect) | Uncle or Older brother |

| Lalëbukri | Uncle by marriage | |

| Vova | motra e madhe | Older sister |

| Tata | babai or Tata (dialect) | Father |

| Mëmë | nëna or mamaja | Mother |

| Midhe'/ Mëdhema | edhe | Also |

| Lluai | vëllai | brother |

| Drëngova / also Kapirta | Kuptova | I understood |

| Sprasmja | Fundi | end |

| Fundi/Bythi | Bythi | buttocks |

| Jotëm përherë të thëshjë të mos hash nga tajuri çë ngë ka' klënë pastruam! | Jot ëmë përherë/gjithmonë të thoshte të mos hash nga pjata që nuk është pastruar | Your mother always said don't eat from plates that haven't been cleaned! |

| Kemi besë se ai ngë i ftes | besojmë se ai nuk ka faj | We believe he is not at fault |

Compared with Standard Tosk Albanian (second row),

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grammar comparison

There are many elements of Arberesh grammar that differ considerably from Albanian, for example:

| Arbërisht | Shqip | Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ka shkosh | do të kalosh | You will pass | Arbërisht uses the common Balkan participle ka, whereas Shqip uses do which translates as 'want', which is also a feature of the Balkan sprachsbund |

| flini alluras/anangasij | folni/flisni shpejt | Speak soon (pl.) | |

| flëni | flini | Sleep! (pl.) | |

| bëjëm të shkonj | më lër të kaloj | Let me pass | Shqip uses 'allow me to pass' whereas Arbërisht uses 'we do to pass' and 'able to pass'. |

| vajta | shkova | I went | Arbërisht conjugates from the Tosk word të vete whereas shkova means 'I passed' in Arbërisht |

| ke gjegjur | ke dëgjuar | You have heard | |

| i papas zën fill parkalesin | prifti fillon lutjen | The priest starts the prayer | |

| stisi | ishte ndërtuar | It was built | |

| Jo, ngë e ka' parë | Jo, nuk e kam parë | No, I haven't seen it | |

| jam e flas, je flet, ai isht e flet, ajo isht e flet, jem'e flasjëm, jan'e flasjën, jan'e flini | po flas, ti po flet, ai po flet, ajo po flet, po flasim, po flasin, po flisni | I am talking, you are talking, he is talking, she is talking, we are talking, they are talking, you (pl) are talking | The present continuous is marked with the structure 'I am, You are, He is, She is, We are, They are etc. Whereas Shqip uses po which literally means 'yes' |

| ki’ të zgjoneshjëm | duhet të ishim zgjuar | We should have got up | |

| te ku ë Mërì? | ku është Maria? | Where is Maria? | The locative marker te which literally means 'to' is added before ku 'where'. (A similar phenomena occurs in Welsh English and West Country English i.e. 'Where to you going?' or 'Where's he to?') |

| Mërìa rri alartë | Maria jeton lartë | Maria lives upstairs | |

| Si ë Zotërote? | Si jeni ju, Zotëri? | How are you sir? | The polite or formal is marked by use of Zotërote with ju being reserved for the plural only |

Name

The name Arbërishte is derived from the ethnonym "Albanoi", which in turn comes from the toponym "Arbëria" (Greek: Άρβανα), which in the Middle Ages referred to a region in what is today Albania (Babiniotis 1998). Its native equivalents (Arbërorë, Arbëreshë and others) used to be the self-designation of Albanians in general. Both "Arbëria" and "Albania/Albanian" go further back to name forms attested since antiquity.

Within the Arbëresh community the language is often referred to as "Tarbrisht" or "Gjegje." The origin of the term "gjegje" is uncertain, however this does mean "listen" in Arbërisht. Gheg is also the name of one of the two major dialects of Albanian as spoken in the Balkans. The name Gheg is derived from the term initially used by the Orthodox Christian population of pre-Ottoman Albania for confessional denotation when referring to their Catholic neighbors who converted to Catholicism to better resist the Orthodox Serbs.[11]

Arbëresh names

Every Italo-Albanian person is given a legal Italian name and also a name in Albanian Arbërisht. Quite often the Arbëresh name is merely a translation of the Italian name. Arbëresh surnames are also used amongst villagers but do not carry any legal weight; the Arbëresh surname is called an "ofiqe" in Arbërisht. Some Arbëresh 'ofiqe' are 'Butijuni', 'Pafundi', 'Skarpari' (shoemaker from Italian word 'scarpa').

Examples of Italian names and their Arbëresh equivalents:

| Italian | Arbëresh |

|---|---|

| Giuseppe | Zef, Josif |

| Marco | Marku |

| Luca | Lekë, Lekini/u |

| Francesco | Frangjishk, Nxhiku, Çiku |

| Nicola | Kola, Koll |

| Angelica | Ëngjëlliqe |

| Gabriele | Gavril, Bjelli |

| Alessandro | Lishëndri |

| Elena, Elenuccia | Lena, Lenuca |

| Giacomo | Minu, Minikeli, Jakini |

| Mario, Mariuccio | Marjucë |

| Emanuele, Manuele | Manueli |

| Maria | Mëria |

| Martino | Martini, Tinuçë |

| Gaetano | Tani |

| Eleuterio | Lëfteri |

| Antonio | Ndon, Nton, Gjon |

| Gaspare | Ghaspani |

| Domenica, Mimma | Mima |

| Lorenzo | Lloreu |

| Giovanni | Jani, Xhuan, Vanù |

| Demetrio | Mitri |

| Spiridione | Spiridhon, Dhoni, Spiro |

| Rosalia | Sallja |

| Tommaso, Tommasino | Masinë |

| Cosimo | Gësmëni |

| Saverio | Shaverë |

| Andrea | Ndrica |

Writing system

The language is not usually written outside of the church and a few highly educated families, but officials are now using the standard Albanian alphabet, which is used on street signs in villages as well as being taught in schools.

Language samples

Pronouns

| Personal pronouns | Possessive pronouns | |||

| 1Sg. | u | I | jim | mine |

| 2Sg. | ti | you | jytë | yours |

| 3Sg.m. | aji | he | i/e tíj | his |

| 3Sg.f. | ajo | she | i/e saj | hers |

| 1Pl. | na | we | jynë | ours |

| 2Pl. | ju | you | juaj | yours |

| 3Pl.m. | ata | they (m.) | atyre | theirs (m.) |

| 3Pl.f. | ato | they (f.) | atyre | theirs (f.) |

Verbs

Arbëresh verbs often differ, somewhat drastically, from their Standard Albanian counterparts.

| Mood | Tense | Number and person | English equivalent (only sg. 1st) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||||||

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||

| Indicative | Pluperfect | kisha burë | kishe burë | kishë burë | kishëm burë | kishni burë | kishin burë | I had done |

| Imperfect | ish'e buja (she buja) | ish'e buje (she buje) | ish'e bun (she bun) | ishm'e bujëm | ishn'e buni | ishn'e bujën | I was doing | |

| Perfect | bura | bure | burë | burëm | burën | burën | I did | |

| Present perfect | ka burë | ka burë | ka burë | ka burë | ka burë | ka burë | I have done | |

| Present | bunj | bun | bun | bujëm | buni | bujën | I do, I am doing | |

| Future | ka bunj | ka bun | ka bun | ka bujëm | ka buni | ka bujën | I will do | |

| Imperative | Present | – | buje! | – | – | buni! | – | do! (2nd person only) |

| Type | Form | English |

|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | të bunj | to do |

| Gerund | jam e bunj | doing |

| The verb HAVE | The verb BE | |||||||

| Pres. | Imperf. | Subj.Impf. | Subj.Perf. | Pres. | Imperf. | Subj.Impf. | Subj.Perf. | |

| 1Sg. | kam | keshë | të kem | të keshë | jam | jeshë | të jem | të jeshë |

| 2Sg. | ke | keshe | të kesh | të keshe | je | jeshe | të jesh | të jëshe |

| 3Sg. | ka | kish | të ket | të kish | ishtë, është | ish | të jet | të ish |

| 1Pl. | kemi | keshëm | të kemi | te keshëm | jemi | jeshëm | të jeshëm | të jeshëm |

| 2Pl. | kini | keshëtë | të kini | te keshëtë | jini | jeshëtë | të jeshëtë | të jeshëtë |

| 3Pl. | kanë | kishnë | të kenë | të kishnë | janë | ishnë | të jenë | të ishnë |

Some common phrases

| Arberesh | English |

| Falem | Hello. |

| Çë bun? Si rri? | What are you doing? How are you? |

| Jam shum mirë | I am very well |

| Ghracji, je mirë? | Thank you, and are you well? |

| O, jam midhema mirë. | Yes, I'm fine too. |

| Flet arbërisht? | Do you speak Arbërisht? |

| Ka vjen? | Where are you from? |

| Jam gjimps arbëresh | I'm half Arbëresh |

| Mëma jime ë lëtire | My mother is Italian |

| Ju parkales | Please |

| Gëzonem të të njoh | Pleased to meet you |

| Mirmenat | Good morning |

| Shihemi | See you soon |

| Gjegjemi aghuras | We'll speak soon |

| Si thrite? | What's your name? |

| Mua më thonë Marieja | My name is Maria |

| Ëj/ò | Yes (Piana degli Albanesi) |

| Arà/ëj | Yes (Santa Cristina Gela) |

| Ora/ëj | Yes (Contessa Entellina) |

| Jo | No |

Prepositions

| Arbëresh | English |

|---|---|

| te | to |

| nga/ka | from |

| prapa | behind |

| te ana e | beside, next to |

| kundrë | against |

| me | with |

| 'e (f), i (m), të (n & pl) | of |

| brënda | within, inside |

| jasht | outside |

| siprë | on, above |

| njera | until |

| për/pë' | for |

| nën | under |

| mjes | between, among |

Demonstrative pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns replace nouns once they are able to be understood from their context.

| Arbëresh | English |

|---|---|

| ai/ajo | that (m/f) |

| ata/ato | those (m/f) |

| ki/kjo | this (m/f) |

| rta/rto | these |

| mosgjë/gjë | none |

Sample text

Shërbesa e Kurorës - The Arbëresh Marriage Ceremony

Zoti : Gjergji, do ti të marsh për gruja Linën çë ë ke këtú te ana, si urdhuron Klisha Shejte, e të qëndrosh lidhur me atë në të mirën si edhé në të ligën gjithë ditët e gjellës tënde?

Priest: Do you George want to take as your wife Lina who is present here according to the instructions of the Holy Church and to be faithful through the good and the bad all of your life?

Dhëndërri: O, e dua!

Groom: Yes, I want!

Zoti: Bekuar kloft Perëndia jínë nga herë, naní e për gjithëmonë e për jetë të jetëvet.

Priest: blessed be our God for all time, now and always in the centuries of centuries.

Populli: Amín.

People: Amen.

Zoti: Në paqe parkalesjëm t'ën Zonë.

Priest: In peace we pray to the Lord.

Populli: Lipisí, o i Madh'yn'Zot.

People: Our Great God, we beseech you.

Bekimi të unazavet

Zoti: Me këtë unazë shërbëtori i Perëndis, Gjergji, lidhet me shërbëtorën e Perëndis, Lina, në embër të Atit, të Birit e të Shpirtit Shejt.

Priest: The servant of God, George, is tied to the servant of God, Lina, in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Zoti jep krinjët e këndon Msalmin 127: Të limë atá çë i trëmben t'ynë Zoti e çë jecjën te udhët e Tij.

the priest delivers the candles and intones Psalm 127 Make happy those who fear the Lord and may they walk in His ways.

Lëvdi tij, o i madh'yn'Zot, lëvdi tij. Dhóksa si, o Theós imón, dhóksa si Glory to you, our God, glory to you.

Se ti ka hashë bukën e shërbëtyrës s'duarvet tote. Lumë ti e fatbardhë ka jeshë. Jotë shoqe ka jet si dhri me pemë te muret e shpis tënde. Bijët tatë si degë ullinjësh rrethë triesës tënde. Shi kështú ka jet bekuar njeriu çë ka trëmbësirën e Perëndisë.

That you will eat the bread of the work of your hands. You will be happy and enjoy all that is good. See your wife as a fertile vine in the intimacy of your home. That your daughters will be like olive branches around your table. That those who fear the Lord will be blessed.

Swadesh list (comparative list)

| No. | English | Arberesh Arbërisht, T'arbërisht |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | u |

| 2 | you (singular) | ti |

| 3 | he | ai, ajo |

| 4 | we | na, ne |

| 5 | you (plural) | ju |

| 6 | they | ata, ato |

| 7 | this | ki, kjo |

| 8 | that | ai, ajo |

| 9 | here | rtu |

| 10 | there | atì, atje |

| 11 | who | kush |

| 12 | what | çë |

| 13 | where | ku |

| 14 | when | kur |

| 15 | how | si |

| 16 | not | nëngë/ngë |

| 17 | all | gjith |

| 18 | many | shum, burin |

| 19 | some | ca |

| 20 | few | dica |

| 21 | other | jetrë |

| 22 | one | një |

| 23 | two | di |

| 24 | three | tri, tre |

| 25 | four | kart |

| 26 | five | pes |

| 27 | big | i math, e madhe |

| 28 | long | i, e glat |

| 29 | wide | i, e trash |

| 30 | thick | i, e trash |

| 31 | heavy | i rënd, e rëndë |

| 32 | small | i, e vogël |

| 33 | short | i, e shkurtur |

| 34 | narrow | i, e holl |

| 35 | thin | i, e hollë |

| 36 | woman | grua |

| 37 | man (adult male) | burr |

| 38 | man (human being) | njeri |

| 39 | child | fëmijë |

| 40 | wife | shoqja |

| 41 | husband | shoqi |

| 42 | mother | mëma |

| 43 | father | tata |

| 44 | animal | animall |

| 45 | fish | pishk |

| 46 | bird | zog |

| 47 | dog | qen |

| 48 | louse | |

| 49 | snake | |

| 50 | worm | Gjalprrë |

| 51 | tree | lis |

| 52 | forest | voshku |

| 53 | stick | |

| 54 | fruit | |

| 55 | seed | |

| 56 | leaf | |

| 57 | root | |

| 58 | bark (of a tree) | |

| 59 | flower | lule |

| 60 | grass | |

| 61 | rope | |

| 62 | skin | likur |

| 63 | meat | mish |

| 64 | blood | gjak |

| 65 | bone | asht |

| 66 | fat (noun) | |

| 67 | egg | ves |

| 68 | horn | |

| 69 | tail | |

| 70 | feather | |

| 71 | hair | krip |

| 72 | head | krie |

| 73 | ear | vesh |

| 74 | eye | si |

| 75 | nose | hun |

| 76 | mouth | |

| 77 | tooth | |

| 78 | tongue (organ) | gluhë |

| 79 | fingernail | |

| 80 | foot | këmb |

| 81 | leg | këmb |

| 82 | knee | gluri |

| 83 | hand | dor |

| 84 | wing | krah |

| 85 | belly | bark |

| 86 | guts | |

| 87 | neck | |

| 88 | back | kurrdhux |

| 89 | breast | |

| 90 | heart | zëmbrë |

| 91 | liver | |

| 92 | to drink | pi |

| 93 | to eat | ha |

| 94 | to bite | |

| 95 | to suck | |

| 96 | to spit | |

| 97 | to vomit | |

| 98 | to blow | |

| 99 | to breathe | marr frim |

| 100 | to laugh | qesh |

| 101 | to see | shoh |

| 102 | to hear | gjegjëm |

| 103 | to know | di |

| 104 | to think | pincar, mëndonj |

| 105 | to smell | |

| 106 | to fear | |

| 107 | to sleep | flë |

| 108 | to live | rronj |

| 109 | to die | vdes |

| 110 | to kill | vras |

| 111 | to fight | |

| 112 | to hunt | |

| 113 | to hit | |

| 114 | to cut | |

| 115 | to split | |

| 116 | to stab | |

| 117 | to scratch | |

| 118 | to dig | |

| 119 | to swim | |

| 120 | to fly | |

| 121 | to walk | jec |

| 122 | to come | vinj |

| 123 | to lie (as in a bed) | ngulëm |

| 124 | to sit | t'ujëm |

| 125 | to stand | |

| 126 | to turn (intransitive) | |

| 127 | to fall | bie |

| 128 | to give | jap |

| 129 | to hold | |

| 130 | to squeeze | |

| 131 | to rub | |

| 132 | to wash | lah |

| 133 | to wipe | |

| 134 | to pull | |

| 135 | to push | |

| 136 | to throw | |

| 137 | to tie | |

| 138 | to sew | |

| 139 | to count | |

| 140 | to say | them |

| 141 | to sing | këndonj |

| 142 | to play | loz |

| 143 | to float | |

| 144 | to flow | |

| 145 | to freeze | |

| 146 | to swell | dhëmbronj |

| 147 | sun | diell |

| 148 | moon | hënxë |

| 149 | star | illzë |

| 150 | water | ujë |

| 151 | rain | shi |

| 152 | river | lum |

| 153 | lake | ghaghu, liqen |

| 154 | sea | dejt |

| 155 | salt | krip |

| 156 | stone | gur |

| 157 | sand | |

| 158 | dust | |

| 159 | earth | dhe |

| 160 | cloud | |

| 161 | fog | |

| 162 | sky | qiell |

| 163 | wind | erë |

| 164 | snow | zborë |

| 165 | ice | akull |

| 166 | smoke | |

| 167 | fire | zjarr |

| 168 | ash | |

| 169 | to burn | djeg |

| 170 | road | dhrom, rrugë |

| 171 | mountain | mal |

| 172 | red | kuq |

| 173 | green | virdhi |

| 174 | yellow | |

| 175 | white | i bardh, e bardhe |

| 176 | black | i zi, e zezë |

| 177 | night | natë |

| 178 | day | ditë |

| 179 | year | vit |

| 180 | warm | vap |

| 181 | cold | titim |

| 182 | full | plot |

| 183 | new | i ri, e re |

| 184 | old | i, e vjetrë |

| 185 | good | i,e mirë |

| 186 | bad | i, e lig |

| 187 | rotten | |

| 188 | dirty | |

| 189 | straight | dreqtë |

| 190 | round | |

| 191 | sharp (as a knife) | |

| 192 | dull (as a knife) | |

| 193 | smooth | |

| 194 | wet | lagët |

| 195 | dry | |

| 196 | correct | dreqtë, gjushtu |

| 197 | near | ndanxë |

| 198 | far | llarghu |

| 199 | right | drejtë |

| 200 | left | shtrëmbra |

| 201 | at | te |

| 202 | in | në |

| 203 | with | me |

| 204 | and | e |

| 205 | if | në |

| 206 | because | përçë |

| 207 | name | embër |

Footnotes

- Arbëresh at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Arbëreshë Albanian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- The Italo-Albanian villages of southern Italy Issue 25 of Foreign field research program, report, National Research Council (U.S.) Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.)) Foreign field research program, sponsored by Office of Naval research, report ; no.25 Issue 25 of Report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of (National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council. Publication) Author George Nicholas Nasse Publisher National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, 1964 page 24-25 link

- The Italo-Albanian villages of southern Italy Issue 25 of Foreign field research program, report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.))) Foreign field research program, sponsored by Office of Naval research, report ; no.25 Issue 25 of Report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of (National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council. Publication) Author George Nicholas Nasse Publisher National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, 1964 page 25 link

- The Italo-Albanian villages of southern Italy Issue 25 of Foreign field research program, report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.))) Foreign field research program, sponsored by Office of Naval research, report ; no.25 Issue 25 of Report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of (National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council. Publication) Author George Nicholas Nasse Publisher National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, 1964 page 26 link

- New Albanian Immigrants in the Old Albanian Diaspora: Piana Degli Albanesi. Eda Derhemi

- Mandala', M., & Mandala' M (2005). Siculo-arbëresh e siciliano a contatto: alcune verifiche. In Der Einfluss des Italienischen auf die Grammatik der Minderheitensprachen. Morphologische und syntaktische Probleme (pagg. 13-21)

- A. Guzzetta, La Parlata di Piana degli Albanesi, Parte I - Fonologia, Palermo 1978

- Vito Matranga (January 1995). Ipotesi per il rilevamento dei dati variazionali nei punti albanofoni dell’Atlante linguistico della Sicilia (Report).

- Jochalas Titos, "Sulla problematica dei prestiti Bizantini e Neo-Greci nei dialetti Italo-Albanesi", Balkan Studies 16, 1, 1975, p. 49.

- Ghegs

References

- Babiniotis, Georgios (1985): Συνοπτική Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας με εισαγωγή στην ιστορικοσυγκριτική γλωσσολογία. ["A concise history of the Greek language, with an introduction to historical-comparative linguistics] Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (1998), Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας ["Dictionary of Modern Greek"]. Athens: Kentro Lexikologias.

- Breu, Walter (1990): "Sprachliche Minderheiten in Italien und Griechenland." ["Linguistic minorities in Italy and Greece"]. In: B. Spillner (ed.), Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Frankfurt: Lang. 169-170.

- GHM (=Greek Helsinki Monitor) (1995): "Report: The Arvanites". Online report

- Hammarström, Harald (2005): Review of Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th Edition. LINGUIST List 16.2637 (5 Sept 2005). Online article Vol. II. Livadia: Exandas, 1999 PDF.

- Η Καινή Διαθήκη στα Αρβανίτικα: Διάτα ε Ρε ['The New Testament in Arvanitika']. Athens: Ekdoseis Gerou. No date.

- Kloss, Heinz (1967): "Abstand-languages and Ausbau-languages". Anthropological linguistics 9.

- Salminen, Tapani (1993–1999): Unesco Red Book on Endangered Languages: Europe. .

- Strauss, Dietrich (1978): "Scots is not alone: Further comparative considerations". Actes du 2e Colloque de langue et de littérature écossaises Strasbourg 1978. 80-97.

- Thomason, Sarah G. (2001): Language contact: An introduction. Washington: Georgetown University Press. Online chapter

- Trudgill, Peter (2004): "Glocalisation [sic] and the Ausbau sociolinguistics of modern Europe". In: A. Duszak, U. Okulska (eds.), Speaking from the margin: Global English from a European perspective. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Online article

External links

| Arbëresh language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |