Albanians in Montenegro

Albanians in Montenegro (Albanian: Shqiptarët e Malit të Zi; Serbo-Croatian: Albanci u Crnoj Gori) are an ethnic group in Montenegro of Albanian descent, which constitute 4.91% of Montenegro's total population.[2] They are the largest non-Slavic ethnic group in Montenegro.

.jpg) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 30,439 Ethnic Albanians 4.91% of Montenegro population (2011)[1] 32,671 Albanian speakers 5.27% of Montenegro population (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Montenegro | |

| Ulcinj Municipality | 14,076 |

| Podgorica Municipality | 9,538 |

| Bar Municipality | 2,515 |

| Gusinje Municipality | 1,642 |

| Rožaje Municipality | 1,158 |

| Plav Municipality | 833 |

| Other municipalities | 677 |

| Languages | |

| Albanian, Montenegrin | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam majority Roman Catholic minority | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians, Arbëreshë, Arbanasi, Arvanites, Souliotes | |

Albanians are particularly concentrated in southeastern and eastern Montenegro alongside the border with Albania in the following municipalities including Ulcinj (71% of total population), Tuzi (68%), Plav (19%), Bar (6%), Podgorica (5%) and Rožaje (5%).[3][4]

The largest city of Albanians in Montenegro is Ulcinj, where the headquarters of the Albanian National Council are located.

History

After the territorial expansion of Montenegro towards the Ottoman territories in 1878, Albanians for the first time became citizens of that country. Albanians that obtained Montenegrin citizenship were Muslims and Catholics, and lived in the cities of Bar and Ulcinj, including their surroundings, in the bank of river Bojana and shore of Lake Skadar, as well as in Zatrijebač.[5]

On October 26, 1851, the Arnaut chieftain Gjonlek from Niksic was traveling with 200 Arnauts, given the task of defending Ottoman Albanian interests. They were attacked by Montenegrin forces from Gatsko. On November 11, 1851, Montenegrin forces numbering 30 crossed the Moraca river and attacked the Albanian Ottoman citadel, under Selim Aga, with 27 men. Five were killed and four wounded while Selim Aga pulled back, wounded, into his house and, and in the next morning, he returned to counter the Montenegrins. The Pasha of Scutari immediately began gathering troops.[6]

British traveler George Arbuthnot visited the town in 1862 and noted in his diaries that the fort of Niksic had been built by an influential Albanian lord roughly 200 years ago, according to the inscriptions.[7]

In 1877, Nikšić was annexed by the Montenegrins in accordance with the Treaty of Berlin.[8][9] American author William James Stillman (1828-1901) who traveled in the region at the time writes in his biography of the Montenegrin forces whoo, on the orders of the Prince, began to bomb the Studenica fortress in Niksic with artillery. Around 20 Albanian nizams were inside the fortress who resisted and when the walls breached, they surrendered and asked Stillman if they were going to be decapitated. An Albanian accompanying Stillman translated his words saying they were not going to be killed in which the Albanians celebrated.[10] Shortly after the treaty, the Montenegrin prince began expelling the Albanians from Niksic, Zablyak and Kolasin who then fled to Turkey, Kosovo (Prishtina)[11] and Macedonia.[12] The Montenegrin forces also robbed the Albanians before the expulsion.[13] After the fall of Niksic, Prince Nikola wrote a poem of the victory.[14]

On January 31, 1879, Montenegrin teacher Shcepan Martinovied informed the government of Cetinje that the Muslims of Nikšić desired a school.[15] The Ottomans had opened schools in Niksic, among other neighboring regions, in the 17th and 18th century.[16]

In 1879, Zenel Ahmet Demushi of the Geghyseni tribe, fought with 40 members of the family against Montenegrin forces led by Marko Miljanov in Niksic.[17] The conflict intensified in 1880 when the Albanian irregulars fought under Ali Pash Gucia against the Montenegrin forces led by the brother of Marko Milajnov, Teodor Miljanov, the battle lasting five hours, according to letters written by two local Albanians from Shkodër who participated in the battle.[18]

In 1899, the government in Montenegro arrested Albanians in Niksic and Danilovgrad out of fear that the Malesori would attack the Young Turks in the region, and the captives were held for more than six months in prison.[19]

20th century

After the Balkan wars, new territories inhabited by Albanians became part of Montenegro. Montenegro then gained a part of Malesija, respectively Hoti and Gruda, with Tuzi as center, Plav, Gusinje, Rugovo, Peć and Gjakova.[5] During World War I, Albanian immigrants from Nikšić who had been expelled to Cetinje sent a letter to Isa Boletini saying that they risked starving if he did not send them money for food.[20]

With the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes after World War I, Albanians in Montenegro became discriminated. The position would improve somewhat in Tito's Yugoslavia. In the mid-twentieth century, 20,000 Albanians lived in Montenegro and their number would grow by the end of the century. By the end of the 20th century the number of Albanians began to fall as a result of immigration.[5]

During the Second World War, there were concentration camps in Niksic with Albanian prisoners where the commander of the camp proposed to kill the Albanians with bayonets so that the Red Cross would not recognize them.

Modern period

On 26 November 2019, an earthquake struck Albania. In Montenegro, Albanians from Ulcinj were involved in a major relief effort sending items such as food, blankets, diapers and baby milk through a local humanitarian organisation Amaneti and in Tuzi through fundraising efforts.[21]

Geography

Albanians in Montenegro are settled in the southeastern and eastern parts of the country. Ulcinj Municipality, consisting Ulcinj (Albanian: Ulqin) with the surroundings and Ana e Malit region, along with the newly-formed Tuzi Municipality, are the only municipalities where Albanians are the majority (71% and 68% of the populations respectively). A large number of Albanians also live in the following regions: Bar (Tivar) and Skadarska Krajina (Krajë) in Bar Municipality (2,515 Albanians or 6% of the population), Plav (Plavë) and Gusinje (Guci) in Plav Municipality (2,475 or 19%) and Rožaje (Rozhajë) in Rožaje Municipality (1,158 or 5%).[4]

The largest Albanian settlement is Ulcinj, followed by Tuzi.

Municipalities with an Albanian majority

Of the 24 municipalities in the country, 2 have an ethnic Albanian majority.

| Emblem | Municipality | Area km² (sq mi) |

Settlements | Population (2011) | Mayor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | |||||

| Ulcinj Ulqin |

255 km2 (98 sq mi) | 41 | 19,921 | 70.66% | Ljoro Nrekić (DPS) | |

|

Tuzi Tuz |

236 km2 (91 sq mi) | 37 | 12,096 | 68.45% | Nik Gjeloshaj (AA) |

| — | 2 | — | 78 | 32,017 | — | — |

Anthropology

The Albanians in Montenegro are Ghegs.

Culture

Montenegrin Albanian culture in this region is closely related to the culture of Albanians in Albania, and the city of Shkodër in particular. Their Albanian language dialect is Gheg as of Albanians in Northern Albania.

Religion

According to the 2003 census, 73.37% of Albanians living in Montenegro were Muslim and 26.08% were Roman Catholic.[23] The religious life of Muslim Albanians is organized by the Islamic Community of Montenegro, comprising not only Albanians, but also other Muslim minorities in Montenegro.[24] Catholic Albanians, generally living in Malesija, Šestani and some in the Bar and Ulcinj municipalities, are members of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bar, whose members are mainly Albanians, but which also includes a small number of Slavs. The current Archbishop, Zef Gashi, is an ethnic Albanian.[24]

Language

Albanians in Montenegro speak the Gheg Albanian dialect, namely the northwestern variant, while according to the 2011 Census, there are 32,671 native speakers of the Albanian language (or 5.27% of the population).[4]

According to Article 13 of the Constitution of Montenegro, Albanian language (alongside Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian) is a language in official use, officially recognized as minority language.[25]

Education

The government of Montenegro provides Albanian-language education in the local primary and secondary schools. There is one department in the University of Montenegro, located in Podgorica, offered in Albanian, namely teacher education[5]

Politics

The first political party created by Albanians in this country is the Democratic League in Montenegro, founded by Mehmet Bardhi in 1990. Most Albanians support the country's integration into the EU: during the 2006 Montenegrin independence referendum, in Ulcinj Municipality, where Albanians at that time accounted over 72% of the population, 88.50% of voters voted for an independent Montenegro. Overall, the vote of the Albanian minority secured the country's secession from Serbia and Montenegro.[26]

In 2008, the Albanian National Council (Albanian: Këshilli Kombëtar i Shqiptarëve, abb. KKSH) was established to represent the political interests of the Albanian community. The current chairman of the KKSH is Genci Nimanbegu.

Prominent Individuals

Selected people:

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

| Atheism · Irreligion · Christianity (Catholicism · Orthodoxy · Protestantism) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka dialect · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Calabria Arbëresh · Cham · Lab) |

| History of Albania |

Gallery

Albanians in Montenegro from 1921 to 2011.

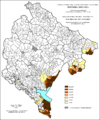

Albanians in Montenegro from 1921 to 2011. Percent of Albanians by municipalities, 1953.

Percent of Albanians by municipalities, 1953. Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1961.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1961. Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1971.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1971. Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1981.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1981. Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1991.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1991. Percent of Albanians by settlements, 2003.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 2003.- Percent of Albanians by settlements, 2011.

References

- "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Crnoj Gori 2011. godine" [Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011] (PDF) (Press release) (in Serbo-Croatian). Statistical office, Montenegro. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). July 12, 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World music: the rough guide. Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

Most of the ethnic Albanians that live outside the country are Ghegs, although there is a small Tosk population clustered around the shores of lakes Presp and Ohrid in the south of Macedonia.

- Stanovništvo Crne Gore prema polu, tipu naselja, nacionalnoj, odnosno etničkoj pripadnosti, vjeroispovijesti i maternjem jeziku po opštinama u Crnoj Gori – monstat.org

- Istorijski Leksikon Crne Gore, Grup of authors, Daily press: Podgorica, 2006 ISBN 86-7706-169-X

- Samtiden: skildringar från verldstheatern (in Swedish) (In Swedish "Den 26 Oktober 1851 tilldrog sig nemligen, att Arnaut-chefen Gjulek från Niksic, hvilken skulle försvara landet mot Montenegrinerna och hålla själv staden i lydnad, hade med 200 arnauter, dem han hemtat till förstärkning från Mostar, blifvit överfallen af en stark Montenegrinsk Ceta i trakten af Gatsko. " Translation: On October 26, 1851, Arnaut commander Gjulek of Niksic, who would defend the country against the Montenegrin and keep the city in obedience, had agreed, with 200 arnauts, which he had taken to reinforce Mostar, to have been attacked by a strong Montenegrin Ceta in the neighborhood of Gatsko. ed.). tryckt hos P. G. Berg. 1858. p. 478. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Arbuthnot, G. (1862). Herzegovina; or Omer Pacha and the Christian Rebels. p. 185. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

Albanian.

- Qosja, Rexhep (1999). Kosova në vështrim enciklopedik (in Albanian). Botimet Toena. p. 81. ISBN 978-99927-1-170-5. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. BRILL. p. 559. ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Stillman, William James (1877). The Autobiography of a Journalist, Volume II by William James Stillman - Full Text Free Book (Part 3/5). Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. Macmillan. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-333-66612-8. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Kultura popullore (in Albanian) (Translation: 118/5000 the process of expelling Albanians from their lands in Koloshin, Niksic Field, Zabjak and elsewhere ”. ed.). Akademia e Shkencave e RSH, Instituti i Kulturës Popullore. 1991. p. 25. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Maloku, Enver (1997). Dëbimet e shqiptarëve dhe kolonizimi i Kosovës (1877-1995) (in Albanian) ("Montenegrin army violence and property theft forced them to flee from Kolasin, Niksic, Shpuza, ..." ed.). Qendra për Informim e Kosovës. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ILLYRIAN LETTERS. 1878. p. 187. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Redžepagić, Jašar (1970). Zhvillimi i arësimit dhe i sistemit shkollor të kombësisë shqiptare në teritorin e Jugosllavisë së sotme deri në vitin 1918 (Translation: "teacher in Niksic, on 31 January 1879 informs school inspector in Cetinje.156 Niksic's Muslims demanded ). Enti i teksteve dhe i mjeteve mësimore i Krahinës Socialiste Autonome të Kosovës. p. 102. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Redžepagić, Jašar (1970). Zhvillimi i arësimit dhe i sistemit shkollor të kombësisë shqiptare në teritorin e Jugosllavisë së sotme deri në vitin 1918. Enti i teksteve dhe i mjeteve mësimore i Krahinës Socialiste Autonome të Kosovës. p. 36. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Brahim Uk Demushi, personalitet i shquar i Tropojës. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Prizrenit, Lidhja Shqiptare e (1978). Me pushkë dhe penë për liri e pavarësi (in Albanian) (Translation: But the peak of this war reached the battle of Nikshiiq in early January 1880. ed.). Shtëpia Botuese "8 Nëntori". pp. 120, 115. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Shpuza, Gazmend (1999). Në prag të pavarësisë (in Albanian) ("... fearing that the Highlanders would attack the Young Turk troops from the territories of Montenegro, the third, arrested and interned the Albanians in Niksic and Danilovgrad, lasting up to six months" ed.). Eagle Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-891654-04-6. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Gjurmime albanologjike: Seria e shkencave historike (in Albanian). Instituti. 1988. p. 251. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Mali i Zi me sy nga Shqipëria- vijojnë ndihmat nga qytete, institucione dhe individë" (in Albanian). TRT. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Recherches albanologiques: Folklore et ethnologie (in French). Pristina: Instituti Albanologijik i Prishtinës. 1982.

- "Montenegrin Census' from 1909 to 2003 - Aleksandar Rakovic". www.njegos.org.

- Bieber, Florian (2003). Montenegro in Transition – Problems of Identity and Statehood. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-8329-0072-4.

- KUSHETUTA E MALIT TË ZI – minmanj.gov.me

- "The Minority Report: Jobless Ethnic Albanians "Let Down by the State"".

.jpg)

.jpg)