Alexandria Eschate

Alexandria Eschate or Alexandria Eskhata (Greek: Ἀλεξάνδρεια Ἐσχάτη), literally "Alexandria the Furthest", was a city founded by Alexander the Great, at the south-western end of the Fergana Valley (modern Tajikistan) in August 329 BCE.[1] It was the most northerly outpost of the Greek Empire in Central Asia. Alexandria Eschate was established on the south bank of the river Jaxartes (Syr Darya), at or close to the site of modern Khujand (Хуҷанд; خجند).[2]

Ἀλεξάνδρεια Ἐσχάτη | |

Coin depicting the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus (230-200 BC) | |

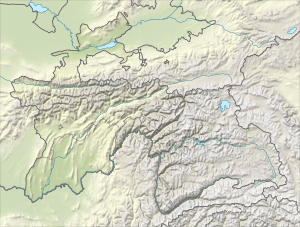

Location of Alexandria Eschate  Alexandria Eschate (Tajikistan) | |

| Alternative name | Alexandria the Farthest |

|---|---|

| Location | Tajikistan |

| Region | Sughd Region |

| Coordinates | 40°15′N 69°38′E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Alexander the Great |

| Founded | August 329 BC |

According to the Roman writer Curtius, Alexandria Ultima retained its Hellenistic culture as late as 30 BC. However, the Han dynasty conquered the city and its surrounding territory in 102 BC, known to the Chinese as Dayuan, after winning the War of the Heavenly Horses.

History

This region where Alexandria Eschate would be founded was ruled over by Persia starting with Xerxes I, and began to be populated by Greeks starting at that time. When "Greeks" (Greek-related and speaking peoples) in other parts of the Persian empire rebelled or otherwise were troublesome, they would be exiled to the far northeast of the Persian empire, the most distant segment from their homelands. This was not uncommon, because the coastline of what is now Turkey was populated by many Greek-culture and language cities. By the time of the fall of Persia to Alexander the Great, many had been exiled to this region north of India, so Greek villages, language, and culture were therefore all common in that area.

As with most other cities founded by Alexander, a group of retired and/or wounded veterans from his army was settled there.

Because Alexandria Eschate was surrounded by Sogdian tribes, and was about 300 km (186 mi) north of the nearest Greek settlement, at Alexandria on the Oxus in Bactria, the Greeks built a 6.0 kilometres (3.7 mi) wall around the city which, according to the ancient authors, was completed in about 20 days.[3] It experienced numerous conflicts with the local population.

From 250 BC, the city likely had greater contact with Bactria, after the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I extended his control into Sogdiana.

Alexandria Eschate was also located around 400 km (249 mi) west of the Tarim Basin (now Xinjiang, China), where other Indo-European peoples, like the Khotanese, Tocharians, Wusun and/or Yuezhi were established. There are indications that Greek expeditions travelled as far as Kashgar. The historian Strabo claims that the Greeks "extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni [possibly the Xiongnu]".[4]

"Seres" meant either China proper – in which case the Greeks achieved the first direct contact between China and a European society, some time around 200 BCE – or the peoples of the Tarim. In any case, a city known to the Chinese as Dayuan, which was mentioned by scholars from the Han dynasty (1st century BCE to 2nd century CE), was almost certainly Alexandria Eschate. The prefix da meant "Great", while the suffix Yuan was the Chinese rendition of Ionians.

Chinese embassies were established in Dayuan, beginning with Zhang Qian opened around 130 BCE. Soon the city and the rest of Dayuan were conquered completely by the Han after winning the War of the Heavenly Horses. This contributed to the opening up the Silk Road from the 1st century BCE.

Archaeological remains

The remains of Alexander's town lie in the tell of the old citadel in Khojand. Although the oldest surface remains of the walls date only to the 10th century, Soviet and Tajik excavations of the site have revealed that below the modern surface are mediaeval, Hellenistic and Achaemenid layers. These layers have revealed fortifications dating to around the 4th century BC.

Other remains include household utensils, armaments and building materials which are exhibited in the Museum of Regional Studies in Khojand. The site has also revealed numerous Hellenistic coins and pottery.[5]

In the Tabula Peutingeriana, below the city there is a rhetorical question in Latin: "Hic Alexander responsum accepit: usque quo Alexander?" (English: Here Alexander accepted the answer: "Until where, Alexander?") — referencing both his insatiable appetite for conquest and a legend from the Alexander romance in which "celestial creatures" admonished Alexander to not pursue further explorations, which would ultimately lead to his untimely death.[6][7]

In fiction

Alexandria Eschate is the final destination of Euxenus, son of Eutychides of the deme of Pallene, the protagonist of Alexander at the World's End by Tom Holt.

Horses of Heaven, by Gillian Bradshaw, is set in Alexandria Eschate, c. 140 BC, talks about the Ferghana horses and the War of the Heavenly Horses fought with Han China.

Footnotes

- Prevas, John. (2004). Envy of the Gods: Alexander the Great's Ill-Fated Journey across Asia, p. 121. Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass. ISBN 0-306-81268-1.

- Khujand, also spelled Khüjand, Khodzhent, Khudchand, and Chodjend, has also been known as Ispisar and Leninabad; Leninobod, Ленинобод, لنینآباد.

- Leriche, Pierre. (1993). "L'extreme-orient hellenistique: Le monde de la brique crue." Les Dossiers d'Archeologie. No. 179, Fevrier 1993, p. 82.

- Strabo XI.II.I

- Negmatov and Belyaeva 1977, Raskopki na tsitadeli Leninabad i lokalizatsiy a Aleksandrii Eskhati. Harmatta 1994 p.100

- Euratlas. "The Tabula Peutingeriana, Section 11: India - Sogdiana". www.euratlas.net. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- Stoneman, Richard (1997-01-01). Alexander the Great. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415150507.

References

See the notes on "Northern Wuyi" = Alexandria Eschate in the draft annotated translation of the 3rd-century Chinese history, the Weilüe, by John Hill at: and