Necktie

A necktie, or simply a tie, is a long piece of cloth, worn, usually by men, for decorative purposes around the neck, resting under the shirt collar and knotted at the throat.

Variants include the ascot, bow, bolo, zipper, cravat, and knit. The modern necktie, ascot, and bow tie are descended from the cravat. Neckties are generally unsized, but may be available in a longer size. In some cultures men and boys wear neckties as part of regular office attire or formal wear. Some women wear them as well but usually not as often as men. Neckties can also be worn as part of a uniform (e.g. military, school, waitstaff), whereas some choose to wear them as everyday clothing attire. Neckties are traditionally worn with the top shirt button fastened, and the tie knot resting between the collar points.[1]

History

Origins

The necktie that spread from Europe traces back to Croatian mercenaries serving in France during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). These mercenaries from the Croatian Military Frontier, wearing their traditional small, knotted neckerchiefs, aroused the interest of the Parisians.[2] Because of the difference between the Croatian word for Croats, Hrvati, and the French word, Croates, the garment gained the name cravat (cravate in French).[3] The boy-king Louis XIV began wearing a lace cravat around 1646, when he was seven, and set the fashion for French nobility. This new article of clothing started a fashion craze in Europe; both men and women wore pieces of fabric around their necks. From its introduction by the French king, men wore lace cravats, or jabots, that took a large amount of time and effort to arrange. These cravats were often tied in place by cravat strings, arranged neatly and tied in a bow.

International Necktie Day is celebrated on October 18 in Croatia and in various cities around the world, including in Dublin, Tübingen, Como, Tokyo, Sydney and other towns.[4][5]

1680–1710: the Steinkirk

The Battle of Steenkerque took place in 1692. In this battle, the princes, while hurriedly dressing for battle, wound these cravats around their necks. They twisted the ends of the fabric together and passed the twisted ends through a jacket buttonhole. These cravats were generally referred to as Steinkirks.

1710–1800: stocks, solitaires, neckcloths, cravats

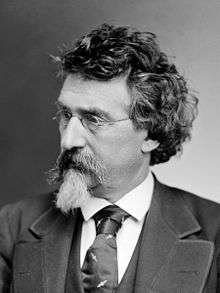

In 1715, another kind of neckwear, called "stocks" made its appearance. The term originally referred to a leather collar, laced at the back, worn by soldiers to promote holding the head high in a military bearing. The leather stock also afforded some protection to the major blood vessels of the neck from saber or bayonet attacks. General Sherman is seen wearing a leather stock in several American Civil War-era photographs.

Stock ties were initially just a small piece of muslin folded into a narrow band wound a few times round the shirt collar and secured from behind with a pin. It was fashionable for men to wear their hair long, past shoulder length. The ends were tucked into a black silk bag worn at the nape of the neck. This was known as the bag-wig hairstyle, and the neckwear worn with it was the stock.

The solitaire was a variation of the bag wig. This form had matching ribbons stitched around the bag. After the stock was in place, the ribbons would be brought forward and tied in a large bow in front of the wearer.

Sometime in the late 18th century, cravats began to make an appearance again. This can be attributed to a group of young men called the macaronis (as mentioned in the song "Yankee Doodle"). These were young Englishmen who returned from Europe and brought with them new ideas about fashion from Italy. The French contemporaries of the macaronis were the incroyables.

1800–1850: cravat, stocks, scarves, bandanas

At this time, there was also much interest in the way to tie a proper cravat and this led to a series of publications. This began in 1818 with the publication of Neckclothitania, a style manual that contained illustrated instructions on how to tie 14 different cravats. Soon after, the immense skill required to tie the cravat in certain styles quickly became a mark of a man's elegance and wealth.[6] It was also the first book to use the word tie in association with neckwear.

It was about this time that black stocks made their appearance. Their popularity eclipsed the white cravat, except for formal and evening wear. These remained popular through to the 1850s. At this time, another form of neckwear worn was the scarf. This was where a neckerchief or bandana was held in place by slipping the ends through a finger or scarf ring at the neck instead of using a knot. This is the classic sailor neckwear and may have been adopted from them.

1860–1920s: bow ties, scarf/neckerchief, the ascot, the long tie

With the industrial revolution, more people wanted neckwear that was easy to put on, was comfortable, and would last an entire workday. Neckties were designed to be long, thin and easy to knot, without accidentally coming undone. This is the necktie design still worn by millions of men.

By this time, the sometimes complicated array of knots and styles of neckwear gave way to neckties and bow ties, the latter a much smaller, more convenient version of the cravat. Another type of neckwear, the ascot tie, was considered de rigueur for male guests at formal dinners and male spectators at races. These ascots had wide flaps that were crossed and pinned together on the chest.

In 1926, a New York tie maker, Jesse Langsdorf, came up with a method of cutting the fabric on the bias and sewing it in three segments.[7] This technique improved elasticity and facilitated the fabric's return to its original shape. Since that time, most men have worn the "Langsdorf" tie. Yet another development during that time was the method used to secure the lining and interlining (known as the swan) once the tie had been folded into shape. Richard Atkinson and Company of Belfast claim to have introduced the slipstitch for this purpose in the late 1920s.

1920s–present day

After the First World War, hand-painted ties became an accepted form of decoration in the U.S. The widths of some of these ties went up to 4.5 inches (11 cm). These loud, flamboyant ties sold very well all the way through the 1950s.

In Britain, regimental stripes have been continuously used in tie designs at least since the 1920s. In Commonwealth countries, necktie stripes run from the left shoulder down to the right side. In Commonwealth countries, only people affiliated with a regiment (or university, school or organisation) should wear a necktie affiliated with that regiment. When Brooks Brothers introduced similar striped ties in the United States around the beginning of the 20th century, they had their stripes run from the right shoulder to the left side, in part to distinguish them from British regimental striped neckties.

Before the Second World War ties were worn shorter than they are today; this was due, in part, to men wearing trousers at the natural waist (more or less at the level of the belly button), and also due to the popularity of waistcoats, where tie length is not important as long as the tips are concealed. Around 1944, ties started to become not only wider, but even more wild. This was the beginning of what was later labeled the Bold Look: ties that reflected the returning GIs' desire to break with wartime uniformity. Widths reached 5 inches (13 cm), and designs included Art Deco, hunting scenes, scenic "photographs", tropical themes, and even girlie prints, though more traditional designs were also available. The typical length was 48 inches (120 cm).

The Bold Look lasted until about 1951, when the "Mister T" look (so termed by Esquire magazine) was introduced. The new style, characterized by tapered suits, slimmer lapels, and smaller hat brims, included thinner and not so wild ties. Tie widths slimmed to 3 inches (7.6 cm) by 1953 and continued getting thinner up until the mid-1960s; length increased to about 52 inches (130 cm) as men started wearing their trousers lower, closer to the hips. Through the 1950s, neckties remained somewhat colorful, yet more restrained than in the previous decade. Small geometric shapes were often employed against a solid background (i.e., foulards); diagonal stripes were also popular. By the early 1960s, dark, solid ties became very common, with widths slimming down to as little as 1 inch (2.5 cm).

The 1960s brought about an influx of pop art influenced designs. The first was designed by Michael Fish when he worked at Turnbull & Asser, and was introduced in Britain in 1965; the term Kipper tie was a pun on his name, as well as a reference to the triangular shape of the front of the tie. The exuberance of the styles of the late 1960s and early 1970s gradually gave way to more restrained designs. Ties became wider, returning to their 4 1⁄2-inch (11 cm) width, sometimes with garish colors and designs. The traditional designs of the 1930s and 1950s, such as those produced by Tootal, reappeared, particularly Paisley patterns. Ties began to be sold along with shirts, and designers slowly began to experiment with bolder colors.

In the 1980s, narrower ties, some as narrow as 1 1⁄2 inches (3.8 cm) but more typically 3 to 3 1⁄4 inches (7.6 to 8.3 cm) wide, became popular again. Into the 1990s, as ties got wider again, increasingly unusual designs became common. Novelty (or joke) ties or deliberately kitschy ties designed to make a statement gained a certain popularity in the 1980s and 1990s. These included ties featuring cartoon characters, commercial products, or pop culture icons, and those made of unusual materials, such as plastic or wood. During this period, with men wearing their trousers at their hips, ties lengthened to 57 inches (140 cm).

At the start of the 21st century, ties widened to 3 1⁄2 to 3 3⁄4 inches (8.9 to 9.5 cm) wide, with a broad range of patterns available, from traditional stripes, foulards, and club ties (ties with a crest or design signifying a club, organization, or order) to abstract, themed, and humorous ones. The standard length remains 57 inches (140 cm), though other lengths vary from 117 cm to 152 cm. While ties as wide as 3 3⁄4 inches (9.5 cm) inches are still available, ties under 3 inches (7.6 cm) wide also became popular, particularly with younger men and the fashion-conscious. In 2008 and 2009 the world of fashion saw a return to narrower ties.

Types

Cravat

In 1660, in celebration of its hard-fought victory over the Ottoman Empire, a crack regiment from Croatia visited Paris. There, the soldiers were presented as glorious heroes to Louis XIV, a monarch well known for his eye toward personal adornment. It so happened that the officers of this regiment were wearing brightly colored handkerchiefs fashioned of silk around their necks. These neck cloths struck the fancy of the king, and he soon made them an insignia of royalty as he created a regiment of Royal Cravattes. The word "cravat" is derived from the à la croate—in the style of the Croats.

Four-in-hand

The four-in-hand necktie (as distinct from the four-in-hand knot) was fashionable in Great Britain in the 1850s. Early neckties were simple, rectangular cloth strips cut on the square, with square ends. The term "four-in-hand" originally described a carriage with four horses and a driver; later, it also was the name of a London gentlemen's club, The Four-in-Hand Driving Company founded in 1856. Some etymologic reports are that carriage drivers knotted their reins with a four-in-hand knot (see below), whilst others claim the carriage drivers wore their scarves knotted 'four-in-hand', but, most likely, members of the club began wearing their neckties so knotted, thus making it fashionable. In the latter half of the 19th century, the four-in-hand knot and the four-in-hand necktie were synonymous. As fashion changed from stiff shirt collars to soft, turned-down collars, the four-in-hand necktie knot gained popularity; its sartorial dominance rendered the term "four-in-hand" redundant usage, shortened "long tie" and "tie".

In 1926, Jesse Langsdorf from New York City introduced ties cut on the bias (US) or cross-grain (UK), allowing the tie to evenly fall from the knot without twisting; this also caused any woven pattern such as stripes to appear diagonally across the tie.

Today, four-in-hand ties are part of men's dress clothing in both Western and non-Western societies, particularly for business.

Four-in-hand ties are generally made from silk or polyester and occasionally with cotton. Another material used is wool, usually knitted, common before World War II but not as popular nowadays. More recently, microfiber ties have also appeared; in the 1950s and 1960s, other manmade fabrics, such as Dacron and rayon, were also used, but have fallen into disfavour. Modern ties appear in a wide variety of colours and patterns, notably striped (usually diagonally); club ties (with a small motif repeated regularly all over the tie); foulards (with small geometric shapes on a solid background); paisleys; and solids. Novelty ties featuring icons from popular culture (such as cartoons, actors, or holiday images), sometimes with flashing lights, have enjoyed some popularity since the 1980s.

Six- and seven-fold ties

A seven-fold tie is an unlined construction variant of the four-in-hand necktie which pre-existed the use of interlining. Its creation at the end of the 19th century is attributed to the Parisian shirtmaker Washington Tremlett for an American customer.[8] A seven-fold tie is constructed completely out of silk. A six-fold tie is a modern alteration of the seven-fold tie. This construction method is more symmetrical than the true seven-fold. It has an interlining which gives it a little more weight and is self tipped.

Skinny tie

A skinny tie is a necktie that is narrower than the standard tie and often all-black. Skinny ties have widths of around 2 1⁄2 inches (6.4 cm) at their widest, compared to usually 3–4 inches (7.6–10.2 cm) for regular ties.[9] Skinny ties were first popularized in the late 1950s and early 1960s by British bands such as the Beatles and the Kinks, alongside the subculture that embraced such bands, the mods. This is because clothes of the time evolved to become more form-fitting and tailored.[2] They were later repopularized in the late 1970s and early 1980s by new wave and power pop bands such as the Knack, Blondie and Duran Duran.[10]

"Pre-tied" ties and development of clip-ons

The "pre-tied", or more commonly, the clip-on, necktie is a permanently knotted four-in-hand or bow tie affixed by a clip or hook, most often metal and sometimes hinged, to the shirt front without the aid of a band around a shirt collar; these ties are close relatives of banded pre-tied ties that make use of a collar band and a hook and eye to secure them. The clip-on tie sees use with children, and in occupations where a traditional necktie might pose a safety hazard, e.g., law enforcement, mechanical equipment operators etc.[12] (see § Health and safety hazard below).

The perceived utility of this development in the history of style is evidenced by the series of patents issued for various forms of these ties, beginning in the late 19th century,[11][13] and by the businesses filing these applications and fulfilling a market need for them. For instance, a patent filed by Joseph W. Less of the One-In-Hand Tie Company of Clinton, Iowa for "Pre-tied neckties and methods for making the same" noted that:

many efforts ... in the past to provide a satisfactory four-in-hand tie so ... that the wearer ... need not tie the knot ... had numerous disadvantages and ... limited commercial success. Usually, such ties have not accurately simulated the Windsor knot, and have often had a[n] ... unconventional made up appearance. Frequently, ... [they were] difficult to attach and uncomfortable when worn ... [and] unduly expensive ... [offering] little advantage over the conventional.[14]

The Inventor proceeded to claim for the invention—the latest version of a 1930s–1950s product line from former concert violinist Joseph Less, Iowan brothers Walter and Louis, and son-in-law W. Emmett Thiessen evolved to be identifiable as the modern clip-on[15]—"a novel method for making up the tie ... [eliminating] the neckband of the tie, which is useless and uncomfortable in warm weather ... [and providing] means of attachment which is effective and provides no discomfort to the wearer", and in doing so achieves "accurate simulation of the Windsor knot, and extremely low material and labor costs".[14] Notably, the company made use of ordinary ties purchased from the New York garment industry, and was a significant employers of women in the pre-war and World War II years.[15]

While the appeal of the pre-tied ties from the perspective of fashion has flowed and ebbed, varieties of clip-on long ties and banded bow ties are still the most common form of child-sized ties in the opening decade of the 21st century.

Types of knot

There are four main knots used to knot neckties. In rising order of difficulty, they are:

- the four-in-hand knot. The four-in-hand knot may be the most common.

- the Pratt knot (the Shelby knot)

- the half-Windsor knot

- the Windsor knot (also redundantly called the "full Windsor"). The Windsor knot is the thickest knot of the four, since its tying has the most steps.

The Windsor knot is named after the Duke of Windsor, although he did not invent it. The Duke did favour a voluminous knot; however, he achieved this by having neckties specially made of thicker cloths.

In the late 1990s, two researchers, Thomas Fink and Yong Mao of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory, used mathematical modeling to discover that 85 knots are possible with a conventional tie (limiting the number "moves" used to tie the knot to nine; longer sequences of moves result in too large a knot or leave the hanging ends of the tie too short). The models were published in academic journals, while the results and the 85 knots were published in layman's terms in a book entitled The 85 Ways to Tie a Tie.[16] Of the 85 knots, Fink and Mao selected 13 knots as "aesthetic" knots, using the qualities of symmetry and balance. Based on these mathematical principles, the researchers came up with not only the four necktie knots in common use, but nine more, some of which had seen limited use, and some that are believed to have been codified for the first time.

Other types of knots include:

- the small knot (also "oriental knot", "Kent knot"): the smallest possible necktie knot. It forms an equilateral triangle, like the half-Windsor, but much more compact (Fink–Mao notation: Lo Ri Co T, Knot 1). It is also the smallest knot to begin inside-out.

- the Nicky knot: an alternative version of the Pratt knot, but better-balanced and self-releasing (Lo Ci Ro Li Co T, Knot 4). Supposedly named for Nikita Khrushchev, it tends to be equally referred to as the Pratt knot in men's style literature. This is the version of the Pratt knot favored by Fink and Mao.

- the Atlantic knot: a reversed Pratt knot, highlighting the structure of the knot normally hidden on the back. In order for the wide blade to remain in front and rightside-out, the knot must begin rightside-out, and the thin end must be wrapped around the wide end. (Ri Co Ri Lo Ci T; not catalogued by Fink and Mao, but would be numbered 5r according to their classification.)

- the Prince Albert knot (also "double knot", "cross Victoria knot"): A variant of the four-in-hand with an extra pass of the wide blade around the front, before passing the wide blade through both of the resultant loops (Li Ro Li Ro Li Co T T, Knot 62). A version knotted through only the outermost loop is known as the Victoria knot (Li Ro Li Ro Li Co T, Knot 6).

- the Christensen knot (also "cross knot"): An elongated, symmetrical knot, whose main feature is the cruciform structure made by knotting the necktie through the double loop made in the front (Li Ro Ci Lo Ri Lo Ri Co T T, Knot 252). While it can be made with modern neckties, it is most effective with thinner ties of consistent width, which fell out of common use after the 19th century.

- the Ediety knot (also "Merovingian knot"): a doubled Atlantic knot, best known as the tie knot worn by the character "the Merovingian" in the 2003 film The Matrix Reloaded. This tie can be knotted with the thin end over the wide end, as with the Atlantic knot, or with the wide end over the thin end to mimic the look seen in the film, with the narrow blade in front. (Ri Co Ri Lo Ci Ri Co Ri Lo Ci T – not catalogued by Fink and Mao, as its 10 moves exceed their parameters.)

Ties as a sign of membership

The use of coloured and patterned neckties indicating the wearer's membership in a club, military regiment, school, professional association (Royal Colleges, Inns of Courts) et cetera, dates only from late-19th century England.[17] The immediate forerunners of today's college neckties were in 1880 the oarsmen of Exeter College, Oxford, who tied the bands of their straw hats around their necks.[17][18]

In the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth countries, neckties are an essential component of the school uniform and are either worn daily, seasonally or on special occasions with the school blazer. In Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand, neckties are worn as the everyday uniform, usually as part of the winter uniform. In countries with no winter such as Sri Lanka, Singapore, Malaysia and many African countries, the necktie is usually worn as part of the formal uniform on special occasions or functions. Neckties may also denote membership of a house or a leadership role (i.e. school prefect, house captain, etc.).

The most common pattern for such ties in the UK and most of Europe consists of diagonal stripes of alternating colours running down the tie from the wearer's left. Note that neckties are cut on the bias (diagonally), so the stripes on the source cloth are parallel or perpendicular to the selvage, not diagonal. The colours themselves may be particularly significant. The dark blue and red regimental tie of the Household Division is said to represent the blue blood (i.e. nobility) of the Royal Family, and the red blood of the Guards.

In the United States, diagonally striped ties are commonly worn with no connotation of group membership. Typically, American striped ties have the stripes running downward from the wearer's right (the opposite of the European style).[19] However, when Americans wear striped ties as a sign of membership, the European stripe style may be used.

An alternative membership tie pattern to diagonal stripes is either a single emblem or a crest centered and placed where a tie pin normally would be, or a repeated pattern of such motifs. Sometimes, both types are used by an organization, either simply to offer a choice or to indicate a distinction among levels of membership. Occasionally, a hybrid design is used, in which alternating stripes of colour are overlaid with repeated motif pattern.

Use by women

Neckties are sometimes part of uniforms worn by women, which nowadays might be required in professions such as restaurants and police forces. In many countries, girls are nowadays required to wear ties as part of primary and secondary school uniforms.

Ties may also be used by women as a fashion statement. During the late 1970s and 1980s, it was not uncommon for young women in the United States to wear ties as part of a casual outfit.[20][21] This trend was popularized by Diane Keaton who wore a tie as the titular character in Annie Hall in 1977.[22][23]

In 1993, neckties reappeared as prominent fashion accessories for women in both Europe and the U.S.[24] Canadian recording artist Avril Lavigne wore neckties with tank tops early in her career.

Occasions for neckties

Traditionally, ties are a staple of office attire, especially for professionals. Proponents of the tie's place in the office assert that ties neatly demarcate work and leisure time.[25]

The theory is that the physical presence of something around your neck serves as a reminder to knuckle down and focus on the job at hand. Conversely, loosening of the tie after work signals that one can relax.[25]

Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Group, believes ties are a symbol of oppression and slavery.[26]

Outside of these environments, ties are usually worn especially when attending traditionally formal or professional events, including weddings, important religious ceremonies, funerals, job interviews, court appearances, and fine dining.[27]

Opposition to neckties

The debate between proponents and opponents of the necktie center on social conformity, plainness, professional expectation, and personal, sartorial expression. Quoting architect Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright said: "Form follows function". Applied sartorially, the necktie's decorative function is so criticized.

Christian denominations teaching plain dress

Among many Christian denominations teaching the doctrine of plain dress, long neckties are not worn by men; this includes many Anabaptist communities (such as the Conservative Mennonite Conference), traditional Quakers (who view neckties as contravening their testimony of simplicity), and some Holiness Methodists (such as the Reformed Free Methodists who view neckties as conflicting with the belief in outward holiness).[28][29][30][31]

Other Holiness Methodist denominations, such as the Evangelical Wesleyan Church, allow a long necktie that is black in colour. While Reformed Mennonites, among some other Anabaptist communities, reject the long necktie, the wearing of the bow tie is customary.[28]

Anti-necktie sentiment

In the early 20th century, the number of office workers began increasing. Many such men and women were required to wear neckties, because it was perceived as improving work attitudes, morale, and sales. Removing the necktie as a social and sartorial business requirement (and sometimes forbidding it) is a modern trend often attributed to the rise of popular culture. Although it was common as everyday wear as late as 1966, over the years 1967–69, the necktie fell out of fashion almost everywhere, except where required. There was a resurgence in the 1980s, but in the 1990s, ties again fell out of favor, with many technology-based companies having casual dress requirements, including Apple, Amazon, eBay, Genentech, Microsoft, Monsanto, and Google.[32]

In western business culture, a phenomenon known as Casual Friday has arisen, in which employees are not required to wear ties on Fridays, and then—increasingly—on other, announced, special days. Some businesses have extended casual-dress days to Thursday, and even Wednesday; others require neckties only on Monday (to start the work week). At the furniture company IKEA, neckties are not allowed.[33]

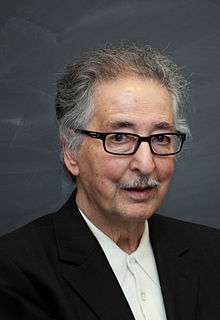

An example of anti-necktie sentiment is found in Iran, whose theocratic rulers have denounced the accessory as a decadent symbol of European oppression. In the late 1970s (at the time of the Islamic Revolution), members of the US press even metonymized Iran's hardliners as turbans and its moderates as neckties. To date, most Iranian men in Iran have retained the Western-style long-sleeved collared shirt and three-piece suit, while excluding the necktie. The majority of Iranian men abroad wear neckties.[34]

Neckties are viewed by various sub- and counter-culture movements as being a symbol of submission and slavery (i.e., having a symbolic chain around one's neck) to the corrupt elite of society, as a "wage slave".[35]

For 60 years, designers and manufacturers of neckties in the United States were members of the Men's Dress Furnishings Association but the trade group shut down in 2008 as a result of declining membership due to the declining numbers of men wearing neckties.[36]

In 2019, presidential candidate Andrew Yang drew attention when he appeared on televised presidential debates without a tie.[37] Yang dismissed media questions about it, saying that voters should be focused on more important issues.[38]

Health and safety hazards

Necktie wearing presents some risks for entanglement, infection, and vasoconstriction. A 2018 study published in the medical journal Neuroradiology found that a Windsor knot tightened to the point of "slight discomfort" could interrupt as much as 7.5 percent of cerebral blood flow.[39][40] A 2013 study published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology found increased intraocular pressure in such cases, which can aggravate the condition of people with weakened retinas.[41] There may be additional risks for people with glaucoma.

Entanglement is a risk when working with machinery or in dangerous, possibly violent, jobs such as police officers and prison guards, and certain medical fields.[42]

Paramedics performing life support remove an injured man's necktie as a first step to ensure it does not block his airway. Neckties might also be a health risk for persons other than the wearer. They are believed to be vectors in disease transmission in hospitals. Notwithstanding such fears, many doctors and dentists wear neckties for a professional image. Hospitals take seriously the cross-infection of patients by doctors wearing infected neckties,[43] because neckties are less frequently cleaned than most other clothes. On September 17, 2007, British hospitals published rules banning neckties.[44] In such a context, some instead prefer to use bow ties due to their short length and relative lack of hindrance.

In the UK, it is a popular prank to pull someone's tie so that it tightens. This prank, known as "peanutting" or "squatknotting", is often used to embarrass the victim and can also be used for more severe bullying. In March 2008, a 13-year-old boy from Oxted, in Surrey, was rushed into hospital with spinal injuries after being "peanuted". He was kept hospitalized for three days.[45]

See also

- Ascot tie

- Bolo tie

- Bow tie

- Cravat

- History of Western fashion

- Panama hat

- Prince Claus of the Netherlands and the "Declaration of the Tie"

- Knit Tie

- Tie chain

- Tie clip

- Tie press, a device used to combat creasing in ties without heat-related damage.

References

- Agins, Teri (August 1, 2012). "When Is it Time to Loosen the Tie?". Wall Street Journal.

- "The Evolution of the Necktie". tie-a-tie.net. August 14, 2013.

- "Academia Cravatica". Academia-cravatica.hr. Archived from the original on February 15, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- 18TH OCTOBER – THE CRAVAT DAY! Archived July 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Academia-cravatica.hr (October 18, 2003). Retrieved on 2013-08-08.

- Tie Talk. Tietalk.vpweb.com.au (June 30, 2010). Retrieved on 2013-08-08.

- Chenoune, Farid (1993). A History of Men's Fashion. Paris: Flammarion. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-2-08-013536-0.

- J.E. Langsdorf, 1923, Necktie, US patent 1448453

- Gemma, Pierre (1983). Da quando? Le origini degli oggetti della vita quotidiana (in Italian). Edizione Dedalo. p. 88. ISBN 978-88-220-4502-7. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- Murphy, H. Lee (January 2, 2012). "In a bind about tie widths? Skinny is in, but anything goes". Crain's Chicago Business.

- Pareles, Jon (April 5, 2005). "Nostalgia for the Skinny Tie as Duran Duran Returns". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- Waehner, Johann (1875) U.S. Patent 170,651 "Improvement in neck-tie fasteners" (hook-type of clip-on)

- Agricultural Safety: Preventing Injuries B 1255. The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

- Jacobowitz, Mayer (1896) U.S. Patent 569,498 "Necktie" (band-toe attachment)

- Less, Joseph W (1957) U.S. Patent 2,804,627 "Pre-tied neckties and methods for making the same".

- The beginning of the effort apparently was a version that used a pre-knotted design and slipped the tie's narrow end through "slot" in back of the knot. Clinton County Historical Society (2003). Clinton, Iowa. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-7385-2349-1.

- Fink, Thomas; Yong Mao (November 5, 2001) [October 3, 2000]. The 85 Ways to Tie a Tie: the science and aesthetics of tie knots (1st Paperback ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 1-84115-568-3.

- "The Finest Neckties". Forbes. November 26, 2016.

- Roetzel, Bernhard (1999). Gentleman: a timeless fashion. Könemann. p. 72. ISBN 3-8290-2029-5.

- Dickinson, Rachel J. (June 18, 2004). "Ties have a history of hanging around." The Cincinnati Post.

- Sagert, Kelly Boyer (2007). The 1970s. Greenwood. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-313-33919-6.

- Peterson, Amy T. (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through American History 1900 to the present. Greenwood Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-313-33395-8.

- "Calender." Seventeen Nov. 2002: 24.

- Pendergast, Sara; Tom Pendergast; Sarah Hermsen (2004). Fashion, Costume, and Culture. Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear Through the Ages. Detroit: UXL. pp. 950–951. ISBN 0-7876-5422-1.

- Kirkham, Pat (1999). The Gendered Object (2nd ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-7190-4475-8.

- "Why every man should wear a tie to work". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "Why Richard Branson Won't Wear a Tie". Bloomberg News. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "Should I Wear A Tie? | Eminence Cufflinks". Eminence Cufflinks. May 15, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- Scott, Stephen (2008). Why Do They Dress That Way?: People's Place Book. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781680992786.

- Kraus, C. Norman (June 13, 2001). Evangelicalism and Anabaptism. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 49.

- Holmes, Scott (2013). "Taking off My Tie: The Adventures in Fashion of a Quaker/Lawyer" (PDF). Journal of North Carolina Yearly Meeting (Conservative). Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- Jones, Charles Edwin (1974). A guide to the study of the holiness movement. Scarecrow Press. p. 685. ISBN 9780810807037.

- "Are ties an outdated fashion or do they still show that you mean business? - Mirror Online". web.archive.org. March 2, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Killela, Amanda (February 26, 2016). "Are ties an outdated fashion or do they still show that you mean business?". Mirror. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Ignatius, David (July 10, 2008). Tehran's Definite 'Maybe'. The Washington Post.

- Bragg, Roy (May 24, 2003). "Tying one on in the office." San Antonio Express.

- Smith, Ray A. (June 4, 2008). "Tie Association, a Fashion Victim, Calls It Quits as Trends Change". Wall Street Journal. pp. A1. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- Patterson, Troy (June 27, 2019). "Democratic Debate 2019: Andrew Yang's Bold Lack of a Tie". New Yorker. New York. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- Harris, Tim (August 2, 2019). "Andrew Yang Rips Presidential Election Process: "We're Like Characters In A Play And We Have To Follow It"". New Yorker. New York. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- Cameron, Christopher (July 23, 2018). "The war against neckties is heating up". New York Post. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- Lüddecke, Robin; Lindner, Thomas; Forstenpointner, Julia; Baron, Ralf; Jansen, Olav; Gierthmühlen, Janne (June 30, 2018). "Should you stop wearing neckties?—wearing a tight necktie reduces cerebral blood flow". Neuroradiology. 60 (8): 861–64. doi:10.1007/s00234-018-2048-7. PMID 29961088.

- Teng, C; R Gurses-Ozden; J M Liebmann; C Tello; R Ritch (August 2003). "Effect of a tight necktie on intraocular pressure". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 87 (8): 946–948. doi:10.1136/bjo.87.8.946. PMC 1771792. PMID 12881330. Retrieved June 8, 2006.

- Kuhn, W. (January 1999). "Violence in the emergency department: Managing aggressive patients in a high-stress environment". Postgraduate Medicine. 105 (1): 143–148. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.01.504. PMID 9924500. Archived from the original on May 30, 2006. Retrieved June 8, 2006.

- Nurkin, Steven; Carl Urban; Ed Mangini; Norielle Mariano; Louise Grenner; James Maurer; Edmond Sabo; James Rahal (May 2004). "Is the Clinicians' Necktie a Potential Fomite for Hospital Acquired Infections?". Paper presented at the 104th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology May 23–27, 2004, New Orleans, Louisiana. p. 204.

- Satter, Raphael; Lindsey Tanner (September 17, 2007). "U.K. Hospitals Issue Doctors' Dress Code". Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Boy was in hospital after 'peanut' tie prank. Daily Mail. March 31, 2008.

Further reading

- Chaille, François (1994). La grande histoire de la cravate. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-201851-2.

- Keers, Paul (1987). A Gentleman's Wardrobe: Classic Clothes and the Modern Man. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-79191-1.

- Dyer, Rod; Spark, Ron (1987). Fit to be Tied: Vintage ties of the Forties and Early Fifties. photography by Steve Sakai (1st ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0-89659-756-3.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: How To Tie A Tie |

| Look up necktie in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Necktie knots at Curlie