Yugoslavs

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 400,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

291,045 (2013) (Yugoslav American)[1] | |

|

38,480 (2016) (Yugoslav Canadian)[2] | |

| 26,883 (2011)[3] | |

|

23,303 (2011) (Yugoslavs in Serbia)[4] | |

| 2,507 (2013) | |

| 1,154 (2011)[5] | |

| 527 (2002)[6] | |

| 331 (2011)[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Orthodox Church, Roman Catholicism, Sunni Islam, Judaism and Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Slavic peoples | |

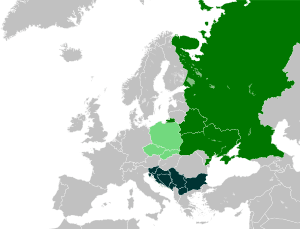

Yugoslavs or Yugoslavians (Serbo-Croatian: Jugoslaveni/Југославени, Jugosloveni/Југословени; Macedonian: Југословени; Slovene: Jugoslovani) is a designation that was originally designed to refer to a united South Slavic people. It has been used in two connotations, the first in an ethnic or supra-ethnic connotation, and the second as a term for citizens of the former Yugoslavia. Cultural and political advocates of Yugoslav identity have historically ascribed the identity to be applicable to all people of South Slav heritage, including those of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. Attempts at uniting Bulgaria into Yugoslavia were however unsuccessful and therefore Bulgarians were not included in the panethnic identification.

Since the dissolution of SFR Yugoslavia and the establishment of South Slavic nation states, the term ethnic Yugoslavs has been used to refer to those who exclusively view themselves as Yugoslavs with no other ethnic self-identification, many of these being of mixed ancestry.

In the early days of Yugoslavia, influential intellectuals Jovan Cvijić and Vladimir Dvorniković advocated that Yugoslavs, as a Yugoslav supra-ethnic nation, had "many tribal ethnicities, such as Croats, Serbs, and others within it.[8]

In the SFR Yugoslavia, the official designation for those who declared themselves simply as Yugoslav was with quotation marks, "Yugoslavs" (introduced in census 1971). The quotation marks were originally meant to distinguish Yugoslav ethnicity from Yugoslav citizenship – which was written without quotation marks. The majority of those who had once identified as ethnic "Yugoslavs" reverted to or adopted traditional ethnic and national identities. Some also decided to turn to sub-national regional identifications, especially in multi-ethnic historical regions like Istria, Vojvodina, or Bosnia (hence Bosnians). The Yugoslav designation, however, continues to be used by many, especially by the descendants of Yugoslav migrants in the United States, Canada and Australia while the country still existed.

Background

Yugoslavism and Yugoslavia

Since the late 18th century, when traditional European ethnic affiliations started to mature into modern ethnic identities, there have been numerous attempts to define a common South Slavic ethnic identity. The word Yugoslav, meaning "South Slavic", was first used by Josip Juraj Strossmayer in 1849.[9] The first modern iteration of Yugoslavism was the Illyrian movement in Habsburg Croatia. It identified South Slavs with ancient Illyrians and sought to construct a common language based on the Shtokavian dialect.[10] The movement was led by Ljudevit Gaj, whose script became one of two official scripts used for the Serbo-Croatian language.[10]

Among notable supporters of Yugoslavism and a Yugoslav identity active at the beginning of the 20th century were famous sculptor Ivan Meštrović (1883–1962), who called Serbian folk hero Prince Marko "our Yugoslav people with its gigantic and noble heart" and wrote poetry speaking of a "Yugoslav race";[11] Jovan Cvijić, in his article The Bases of Yugoslav Civilization, developed the idea of a unified Yugoslav culture and stated that "New qualities that until now have been expressed but weakly will appear. An amalgamation of the most fertile qualities of our three tribes [Serbs, Croats, Slovenes] will come forth every more strongly, and thus will be constructed the type of single Yugoslav civilization-the final and most important goal of our country."[8]

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip shot and killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian throne, and his wife, in Sarajevo. Princip was a member of Young Bosnia, a group whose aims included the unification of the Yugoslavs and independence from Austria-Hungary.[12] The assassination in Sarajevo set into motion a series of fast-moving events that eventually escalated into full-scale war.[13] After his capture, during his trial, he stated "I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be free from Austria."[14]

In June–July 1917, the Yugoslav Committee met with the Serbian Government in Corfu and on 20 July the Corfu Declaration that laid the foundation for the post-war state was issued. The preamble stated that the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were "the same by blood, by language, by the feelings of their unity, by the continuity and integrity of the territory which they inhabit undivided, and by the common vital interests of their national survival and manifold development of their moral and material life." The state was created as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, a constitutional monarchy under the Karađorđević dynasty. The term "Yugoslavs" was used to refer to all of its inhabitants, but particularly to those of South Slavic ethnicity. Some Croatian nationalists viewed the Serb plurality and Serbian royal family as hegemonic. Eventually, a conflict of interest sparked among the Yugoslav peoples. In 1929, King Alexander sought to resolve a deep political crisis brought on by ethnic tensions by assuming dictatorial powers in the 6 January Dictatorship, renaming the country "Kingdom of Yugoslavia", and officially pronouncing that there is one single Yugoslav nation with three tribes. The Yugoslav ethnic designation was thus imposed for a period of time on all South Slavs in Yugoslavia. Changes in Yugoslav politics after King Alexander's death in 1934 brought an end to this policy, but the designation continued to be used by some people.

Philosopher Vladimir Dvorniković advocated the establishment of a Yugoslav ethnicity in his 1939 book entitled "The Characterology of the Yugoslavs". His views included eugenics and cultural blending to create one, strong Yugoslav nation.[8]

There had on three occasions been efforts to make Bulgaria a part of Yugoslavia or part of an even larger federation: through Aleksandar Stamboliyski during and after World War I; through Zveno during the Bulgarian coup d'état of 1934, and through Georgi Dimitrov during and after World War II, but for various reasons, each attempt turned out to be unsuccessful.[15]

Self-identification in Second Yugoslavia

| Republics and Provinces | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia | 0.4 | 1.9 | 8.2 |

| Central Serbia | 0.2 | 1.4 | 4.8 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 8.4 | 1.2 | 7.9 |

| Kosovo | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Macedonia | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Montenegro | 0.3 | 2.1 | 5.3 |

| Slovenia | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| Vojvodina | 0.2 | 2.4 | 8.2 |

| All of Yugoslavia | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5.4 |

After liberation from Axis Powers in 1945, the new socialist Yugoslavia became a federal country, and officially recognized and valued its ethnic diversity. Traditional ethnic identities again became the primary ethnic designations used by most inhabitants of Yugoslavia. However, many people still declared themselves as "Yugoslavs" because they wanted to express an identification with Yugoslavia as a whole, but not specifically with any of its peoples.

Josip Broz Tito expressed his desire for an undivided Yugoslav ethnicity when he stated, "I would like to live to see the day when Yugoslavia would become amalgamated into a firm community, when she would no longer be a formal community but a community of a single Yugoslav nation."[17]

The 1971 census recorded 273,077 Yugoslav, or 1.33% of the total population. The 1981 census recorded 1,216,463 or 5.4% Yugoslavs. In the 1991 census, 5.54% (242,682) of the inhabitants of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared themselves to be Yugoslav.[18] 4.25% of the population of the republic of Montenegro also declared themselves Yugoslav in the same census.

The Constitution of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1990 ratified a Presidency of seven members. One of the seven was to be elected amongst/by the republic's Yugoslavs, thereby introducing the Yugoslavs next to Muslims by nationality, Serbs and Croats into the Constitutional framework of Bosnia and Herzegovina although on an inferior level. However, because of the Bosnian War that erupted in 1992, this Constitution was short-lived and unrealized.

The 1981 census showed that Yugoslavs made up around 8% of the population in Croatia, this to date has been the highest percentage of Yugoslavs within Croatia's borders. The 1991 census data indicated that the number of Yugoslavs had dropped to 2% of the population in Croatia. The 2001 census in Croatia (the first since independence) registered only 176 Yugoslavs.[19] The next census in 2011 registered 331 Yugoslavs in Croatia (0.008% of the population).[20]

Just before and after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, most Yugoslavs switched to more conventional ethnic designations. Nevertheless, the concept has survived into Bosnia and Herzegovina (where most towns have a tiny percentage), and Serbia and Montenegro (2003–2006), which kept the name "Yugoslavia" the longest, right up to February 2003.

After Yugoslavia

Organizations

The Yugoslavs of Croatia have several organizations. The "Alliance of Yugoslavs" (Savez Jugoslavena), established in 2010 in Zagreb, is an association aiming to unite the Yugoslavs of Croatia, regardless of religion, sex, political or other views.[21] Its main goal is the official recognition of the Yugoslav nation in every Yugoslav successor state: Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro.[22]

Another pro-Yugoslav organization advocating the recognition of the Yugoslav nation is the "Our Yugoslavia" association (Udruženje "Naša Jugoslavija"), which is an officially registered organization in Croatia.[23] The seat of Our Yugoslavia is in the Istrian town of Pula,[24] where it was founded on 30 July 2009.[25] The association has most members in the towns of Rijeka, Zagreb and Pula.[26] Its main aim is the stabilisation of relations among the Yugoslav successor states. It is also active in Bosnia and Herzegovina, however, its official registration as an association was denied by the Bosnian state authorities.[23]

The probably best-known pro-Yugoslav organization in Montenegro is the "Consulate-general of the SFRY" with its headquarters in the coastal town of Tivat. Prior to the population census of 2011, Marko Perković, the president of this organization called on the Yugoslavs of Montenegro to freely declare their Yugoslav identity on the upcoming census.[27]

Notable people

The best known example of self-declared Yugoslavs is Marshal Josip Broz Tito who organized resistance against Nazi Germany in Yugoslavia,[28][29] effectively expelled Nazi occupation of Yugoslavia, co-founded the Non-Aligned Movement, and defied Joseph Stalin's Soviet pressure on Yugoslavia. Other people that declared as "Yugoslavs" include intellectuals, entertainers, singers and sportspersons, such as:

- Aleksa Đilas[30]

- Ivan Ergić[31]

- Goran Bregović

- Andrej Grubačić

- Lepa Brena[32]

- Ivica Osim[33]

- Božo Koprivica[34]

- Oliver Dulić[35][36]

- Dževad Prekazi[37][38]

- Magnifico[39][40]

- Milić Vukašinović[41][42]

- Milan Milišić[43]

- Đorđe Đogani[44]

- Branko Đurić

- Branko Milićević "Kockica"[45]

- Ašok Murti[46]

- Ekrem Jevrić[47]

- Joška Broz,[48] the grandson of Josip Broz Tito

- Boris Vukobrat[49]

- Duško Vujošević

- Josip Pejaković

- Branimir Štulić[50]

- Srđa Popović

- Igor Mandić

- Srđan Dragojević

- Bogdan Tanjević

- Miljenko Smoje

- Lepa Smoje

Symbols

The probably most frequently used symbol of the Yugoslavs to express their identity and to which they are most often associated with is the blue-white-red tricolor flag with a yellow-bordered red star in the flag's center,[51] which also served as the national flag of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1945 and 1991.

Prior to World War II, the symbol of Yugoslavism was a plain tricolor flag of blue, white and red, which was also the national flag of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav state in the interwar period.

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Yugoslavs |

|---|

|

| By region |

| Culture |

| History |

| Languages |

| Related groups |

References

- ↑ "2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". American Community Survey 2013. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". statcan.gc.ca.

- ↑ Fact sheets : Ancestry – Serbian (last updated 16 August 2012, retrieved 22 December 2012)

- ↑ Population : ethnicity : data by municipalities and cities (PDF). 2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia. Belgrade: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2012. pp. 14, 20. ISBN 978-86-6161-023-3. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011 Monstat – Statistical Office of Montenegro

- ↑ Slovenian census 2002 (in English)

- ↑ Croatian 2011 Census, detailed classification by nationality

- 1 2 3 Wachte, Andrew (1998). Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia. Stanford University Press. pp. 92–94. ISBN 0-8047-3181-0.

- ↑ Enciklopedia Jugoslavije, Zagreb 1990, pp. 128-130.

- 1 2 Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-521-27485-0.

- ↑ Ivo Banač. The national question in Yugoslavia: origins, history, politics. Cornell University Press, 1984. Pp. 204-205.

- ↑ Banač, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1.

- ↑ "First World War.com Primary Documents: Archduke Franz Ferdinand's Assassination, 28 June 1914". 2002-11-03. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. New York University Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-8147-5561-5.

- ↑ Ahmet Ersoy, Maciej Górny, Vangelis Kechriotis. Modernism: The Creation of Nation-States. Central European University Press, 2010. Pp. 363.

- ↑ Sekulic, Dusko; Massey, Garth; Hodson, Randy (February 1994). "Who Were the Yugoslavs? Failed Sources of a Common Identity in the Former Yugoslavia". American Sociological Review. American Sociological Association. 59 (1): 85. doi:10.2307/2096134.

- ↑ Norbu, Dawa (3–9 April 1999). "The Serbian Hegemony, Ethnic Heterogeneity and Yugoslav Break-Up". Economic and Political Weekly 34 (14): 835.

- ↑ Ethnic composition of Bosnia-Herzegovina population, by municipalities and settlements, 1991. census, Zavod za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine – Bilten no.234, Sarajevo 1991.

- ↑ Population of Croatia 1931–2001

- ↑ http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/census2011/results/htm/H01_01_05/H01_01_05.html

- ↑ U Zagrebu osnovan Savez Jugoslavena (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Portal Jutarnji.hr; 23 March 2010

- ↑ U Zagrebu osnovan Savez Jugoslavena: Imamo pravo na očuvanje baštine Jugoslavije (in Croatian). Index.hr. L.J.; 23 March 2010

- 1 2 Yugoslavs in the twenty-first century: ‘erased’ people openDemocracy.net. Anes Makul and Heather McRobie; 17 February 2011

- ↑ Udruženje "Naša Jugoslavija" osniva Klubove Jugoslavena (in Croatian). Dubrovački vjesnik. Silvana Fable; 25 July 2010

- ↑ Osnovano udruženje "Naša Jugoslavija" u Puli (in Serbian). Radio Television of Vojvodina. Tanjug; 30 July 2009

- ↑ "Naša Jugoslavija" širi se Hrvatskom (in Serbian). Vesti online. Novi list; 27 July 2010

- ↑ Perković pozvao Crnogorce da se izjasne i kao Jugosloveni Archived 5 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (in Serbian). Srbijanet. 03-03-2011

- ↑ Tito and his People by Howard Fast

- ↑ Liberation of Belgrade and Yugoslavia Archived 2 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Intervju: Aleksa Đilas (in Serbian). Radio Television of Serbia. Nenad Stefanović; 2 December 2009

- ↑ "Ich bin ein alter Jugoslawe" (in German). Ballesterer. Fabian Kern; 13 May 2008

- ↑ Lepa Brena u Zagrebu?! (in Croatian). Dnevnik.hr. B.G.; 13 December 2008

- ↑ Nikad nisam skrivao da sam Jugosloven (in Bosnian). E-Novine. Mario Garber; 19 May 2009

- ↑ U fudbalu nema nacionalizma (in Montenegrin). Monitor Online. Nastasja Radović; 16 July 2010

- ↑ Слушам савете многих, али одлуке доносим сам (in Serbian). Evropa magazine/Democratic Party web site. Dragana Đevori

- ↑ "Dulić: 'Nisam Hrvat nego Jugoslaven'" (in Croatian). Dnevnik.hr. 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Kako preživeti slavu Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. (in Serbian). Standard. No. 28; 29 November 2006

- ↑ http://sport.blic.rs/fudbal/domaci-fudbal/ispovest-dzevad-prekazi-za-blicsport-jos-sam-zaljubljen-u-jugoslaviju-sahranite-me-sa/w1bye2t. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Intervju: Magnifico Il Grande. Po domače, Car (in Slovenian). Mladina. Max Modic; 2007/52

- ↑ А1 репортажа – Словенија денес (in Macedonian). A1 Television. Aneta Dodevska; 1 January 2009

- ↑ Tifa: Navijam za mog Miću (in Serbian). Blic. M. Radojković; 4 March 2008

- ↑ Sve za razvrat i blud Archived 25 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. (in Serbian). Glas Javnosti. P. Dragosavac; 17 September 1999

- ↑ Život za slobodu (in Serbian). E-Novine. Dragoljub Todorović; 4 October 2010

- ↑ ЏОЛЕ: Со Слаѓа сум во одлични односи! Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (in Macedonian). Večer. Aleksandra Timkovska; 5 September 2006

- ↑ D. Milićević (12 April 2010). "Uz mališane 33 godine" (in Serbian). Blic. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ↑ Ostao sam ovde iz inata (in Serbian). Blic. Žiža Antonijević; 23 March 2008

- ↑ "Pas do pasa, beton do betona" (in Serbian). Vreme. 2010-07-29.

- ↑ DANI – Intervju: Joška Broz, unuk Josipa Broza Tita (in Bosnian). BH Dani. Tamara Nikčević; 14 August 2009

- ↑ About Boris Vukobrat Archived 27 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Peace and Crises Management Foundation

- ↑ Тивка војна меѓу Србија и Хрватска за Џони Штулиќ!? Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (in Macedonian). Večer . 05-11-2009

- ↑ U Crnoj Gori oko 1.000 Jugoslovena, 100 Turaka, 130 Njemaca... (in Montenegrin). Vijesti. Vijesti online; 12 July 2011

Sources

- Djokić, Dejan (2003). Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918-1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-663-0.

- Jović, Dejan (2009). Yugoslavia: A State that Withered Away. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-495-8.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yugoslavs. |

- S. Mrdjen (2002). "Narodnost u popisima. Promjenljiva i nestalna kategorija" (PDF). Stanovnistvo.

.svg.png)