Dai (Spring and Autumn period)

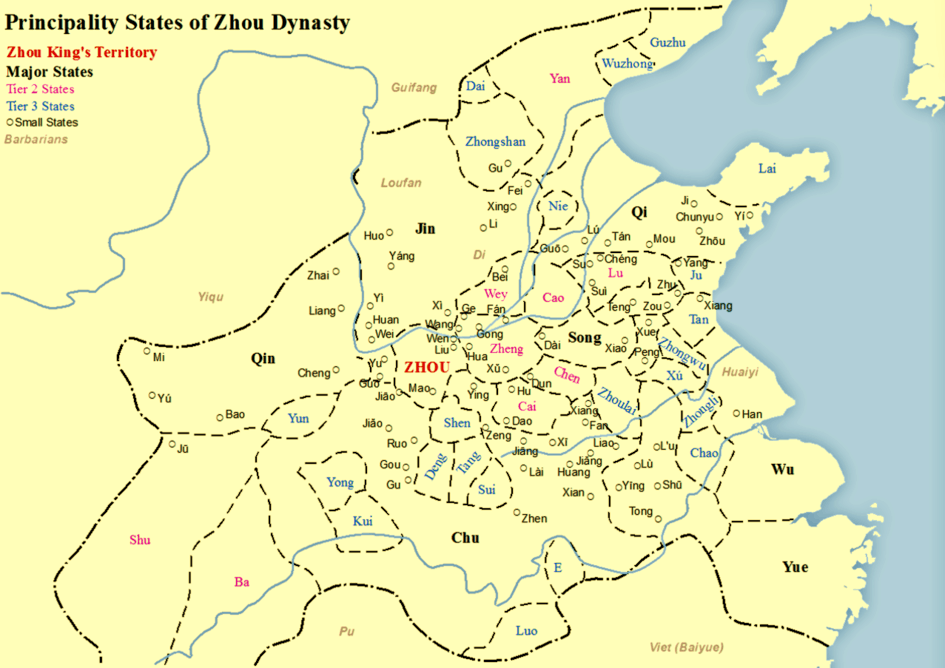

Dai was a state which existed in northern Hebei during the Spring and Autumn Period of Chinese history. Its eponymous capital was located north of the Zhou Kingdom in what is now Yu County, northeast of present-day Yuzhou. It was apparently established by the people known to the ancient Chinese as the Baidi or "White Barbarians". They traded livestock and other goods between Central Asia and the Zhou states prior to their conquest by the Zhao clan of Jin.

Name

Dài (pinyin) and Tai (Wade-Giles) are romanizations of the modern Mandarin way of reading the character 代, which is usually a preposition meaning "for",[1] a verb meaning "to stand for" or "represent",[2] or a noun meaning "era".[2] Its original sense in Old Chinese was "to replace",[3] but the kingdom's name was a transcription of the capital's native name; linguistic reconstruction suggests its Old Chinese pronunciation would have been something like /*lˤək-s/.[3]

The northern Rong, wiped out by Zhao c. 460 BC, were also known as the "Dai Rong" (代戎).[4]

History

The people of Dai were not considered Chinese by the Zhou,[5] but "White Di" (Baidi).[6] The Di were reckoned as "Northern Barbarians" by the Chinese[7] although they possessed towns and organized states on the Chinese model like Dai and Zhongshan.[8] The White Di were first recorded living in land west of the Yellow River in what is now northern Shaanxi.[9] They migrated east of the Ordos Loop into the valleys and mountains of northern Shanxi by the 6th century BC,[10][9] creating states there which were defeated and annexed by the Zhou state of Jin and its successor Zhao. The Di continued eastward and founded Dai and Zhongshan in the northwestern corner of the North China Plain in what is now Hebei.

The capital—known as Dai—was located to the northeast of present-day Yuzhou, Hebei, about 100 miles (160 km) west of Beijing. Its territory included present-day Hunyuan County in Shanxi.[11]

The area acted as middlemen between nomads on the Eurasian Steppe and the Chinese states, supplying the latter with furs,[12] jade, and horses.[13][8] The area's own purebred dogs[14] and horses (t 代馬, s 代马, Dài mǎ) were also well known to the Chinese.[15] Trade passed into Dai territory from the west through the Daoma Pass (t 倒馬關, s 倒马关, Dàomǎ Guān).[15]

The people of Dai were said to be "proud and stubborn, high-spirited and fond of feats of daring and evil", and to disdain practicing trade or agriculture.[12]

Chinese histories record that Zhao Yang (t 趙鞅, s 赵鞅, Zhào Yāng; 517–458 BC), posthumously known as Jianzi (t 趙簡子, s 赵简子, Zhào Jiǎnzi) of Jin's Zhao clan, became ill and was subsequently troubled over which of his sons to name as his heir.[7] He sent them to Mount Chang[lower-alpha 1] to look for a chop he had placed there; only Prince Wuxu (t 趙毋卹, s 赵毋恤, Zhào Wúxù), his son by a Di slave girl, was able to find it.[7] Wuxu was further the only son to realize that the seal had not been the real point of the father's mission.[17] The true seal of a future realm to be found on the mountain was the country of Dai which it overlooked:[17] "As the top of Changshan overlooks Dai, so Dai could be taken".[5] Despite having bound Zhao to Dai through a marriage alliance, wedding one of his daughters to its king, Zhao Yang approved this insight and named Wuxu his successor. Wuxu would become posthumously known as the "Helpful" (t 趙襄子, s 赵襄子, Zhào Xiāngzǐ).[7]

Shortly after becoming head of the Zhao clan (then still part of Jin),[7] Wuxu invited his brother-in-law the king of Dai to a feast. The king, whom the Huainanzi describes as a Mohist convert,[18] came with many of the leading men of his country; Wuxu had them massacred.[19] He then swiftly invaded, overran, and annexed the lands of Dai to his realm[20] in 457 BC.[21][22][19][14][18] His sister the queen of Dai killed herself rather than live under her brother.[7] The expansive territory was given to his nephew Zhou (周, Zhōu).[7]

The Di continued to live in the area after the Zhao conquest.[23] The aftermath of the Zhao conquest is sometimes counted as the first direct contact of the Chinese states with the steppe nomads like the Xiongnu[19] whose threats and invasions shaped much of Chinese history over the next 2,000 years. Later sources record that Zhao even "shared" governance of Dai with "the barbarians" in order to keep it relatively peaceful and to allow invasions against the nomadic Hu, who constantly harassed the area with raids.[24]

Legacy

Dai continued to be used as a name for the surrounding region, eventually becoming the namesake for Dai Prefecture and Dai County in Shanxi.[25] The former site of ancient Dai in Yu County, Hebei, is now preserved as "Dai King City" (代王城, Dàiwángchéng), honoring the memory of the Zhao prince Jia, who created a rump state at Dai to oppose King Zheng of Qin in the decade before his successful unification of China as the Qin Empire.

See also

- Kingdom of Dai, a Zhao successor state in the Warring States Period

- Kingdom of Dai, a Zhao successor state in the Eighteen Kingdoms Period

- Principality of Dai, an imperial realm and appanage under the Han dynasty

Notes

- ↑ During the medieval period, some writers claimed that the princes of Zhao climbed the east terrace of Mount Wutai, overlooking what is now Dai County in Shanxi, although the two territories were only erroneously conflated.[16]

References

Citations

- ↑ "for", Cambridge Dictionary: English–Chinese (Traditional), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- 1 2 Vierkant, Dennis, "代", CC-CEDICT, Hengelo .

- 1 2 Baxter & al. (2014), "代".

- 1 2 Gu (2017), p. 170.

- ↑ Wu (2017), p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Theobald (2000).

- 1 2 Di Cosmo (2002), p. 133.

- 1 2 Wu (2017), p. 28–29.

- ↑ Wu (2004), p. 6.

- ↑ Keller & al. (2007), p. 16.

- 1 2 Di Cosmo (2002), p. 131.

- ↑ Wu (2004), pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 Nienhauser Jr. & al. (2010), p. 8..

- 1 2 Wu (2004), p. 12.

- ↑ Strassberg (1994), p. 357.

- 1 2 Průšek (1971), pp. 189–90.

- 1 2 Major & al. (2010), p. 748.

- 1 2 3 Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 128–9.

- ↑ Xiong (2009), s.v. "Dai".

- ↑ Chin. Culture (1964), p. 130.

- ↑ Huang (1972).

- ↑ Di Cosmo (1991), p. 63.

- ↑ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 136–7.

- ↑ Shanxi Tourism Bureau (2016), s.v. "Dai County".

Bibliography

- "The Origin of the Names of the Counties in Shanxi Province", Official site, Taiyuan: Shanxi Tourism Bureau, 2016 .

- Baxter, William Hubbard III; et al. (2014), Old Chinese: A Reconstruction, Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Chinese Culture, Vol. VI, No. 1, Taipei: Chinese Cultural Research Institute, Oct 1964 .

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (1991), Inner Asia in Chinese History: An Analysis of the Hsiung-nu in the Shih Chi, Bloomington: Indiana University .

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2002), Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Fan Ye, Book of the Later Han .

- Gu Yanwu (1994), "Five Terraces Mountain", in Strassberg, Richard E., Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 357–360 .

- Gu Yanwu (2017), Johnston, Ian, ed., Record of Daily Knowledge and Collected Poems and Essays, Translations from the Asian Classics, New York: Columbia University Press .

- Huang Linshu (1972), 《秦皇長城考修正稿》 [‘’Qín Huáng Chángchéng Kǎo Xiūzhènggǎo, Revised Draft of an Examination the Qin Imperial Great Wall], Hong Kong: Zaoyang Literary Society .

- Keller, Peter C.; et al. (2007), Treasures from Shanghai: 5,000 Years of Chinese Art and Culture, Santa Ana: Bowers Museum

- Liu An; et al. (2010), Major, John; et al., eds., The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, Translations from the Asian Classics, New York: Columbia University Press .

- Průšek, Jaroslav (1971), Chinese Statelets and the Northern Barbarians in the Period 1400–300 B.C., Academia .

- Sima Qian; et al. (2010), Nienhauser, William H. Jr.; et al., eds., The Grand Scribe's Records, Vol. IX: The Memoirs of Han China, Pt. II, Bloomington: Indiana University Press .

- Theobald, Ulrich (2000), "The Feudal State of Zhao", China Knowledge, Tübingen .

- Wu Xiaolong (July 2004), "Exotica in the Funerary Debris in the State of Zhongshan: Migration, Trade, and Cultural Contact" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 142: Silk Road Exchange in China (PDF), Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, pp. 6–16 .

- Wu Xiaolong (2017), Material Culture, Power, and Identity in Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civilizations and Historical Eras, No. 19, Lanham: Scarecrow Press .

External links

- 《代国》 at Baidu Baike (in Chinese)

- 《代国》 at Baike.com (in Chinese)