Munduruku

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 13,755 (2014)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Brazil (Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Munduruku, Portuguese[2] |

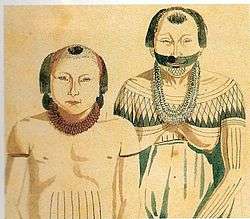

The Munduruku, also known as Mundurucu or Wuy Jugu, are an indigenous people of Brazil living in the Amazon River basin. Some Mundurucu communities are part of the Coatá-Laranjal Indigenous Land.[2] They had an estimated population in 2014 of 13,755.[1]

History

Traditionally the Munduruku's territory, called Mundurukânia in the 19th century, was the Tapajós river valley.[1] In 1788, they completely defeated their ancient enemies the Muras. After 1803 they lived at peace with the Brazilians.

The Munduruku live in southwest of the state of Pará along the Tapajós river and its tributaries in the municipalities of Santarém, Itaituba and Jacareacanga, in the east of the state of Amazonas along the Canumã River in the municipality of Nova Olinda and the municipality of Borba, and in the north of the state of Mato Grosso in the Peixes River region in the municipality of Juara. They usually inhabit forest regions on the margins of navigable rivers, and their traditional villages are in "Tapajós fields", patches of savannah within the Amazon rainforest. The largest numbers live in the Mundurucu Indigenous Territory, with most of the villages along the Cururu River, a tributary of the Tapajós.[3]

Today the Munduruku face threats to their homelands from the dams of the Tapajós hydroelectric complex, illegal gold-panning, and a new waterway construction on the Tapajós River.[1] The reservoir of the proposed Chacorão Dam on the Tapajós river would flood 18,700 hectares (46,000 acres) of the Munduruku Indigenous Territory.[4] The reservoir of the proposed São Luiz do Tapajós Dam on the Tapajós would flood about 7% of the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Territory.[5]

Name

|

| |

|

|

Also known as the Mundurucu, Maytapu, and Cara Preta, the Mundurucu's name for themselves is Wuy Jugu. Oral history says the name "Muduruku" comes from their enemies the Parintintin people and means "red ants," based on the historical Munduruku tactic of attacking en masse.[2]

Culture

The Mundurucu have a distinctive residence pattern. Rather than a pattern based on conjugal or affinal bonds, in the Munduruku villages, all males over the age of thirteen live in one household, and all of the females live with all of the males under thirteen in another.

Language

The Munduruku language is part of the Tupi language family.[2]

They are also notable for their linguistic separation of "us" (their tribe) from "them" (everyone else), the pariwat. Whereas they refer to themselves as the wuujuyû, or "our people", everyone else is spoken of as the equivalent of "prey".

Unlike the Pirahã, the Mundurucu have a numeracy system, albeit limited (similar to that found in some Aboriginal Australian cultures). Pierre Pica was instrumental (in a work done in collaboration with Stanislas Dehaene and Elizabeth Spelke) in revealing the psychophysics and linguistic properties of the Munduruku counting system to the Western world. The Mundurucu have number words up to only five, although each word is not as definite in meaning as number words in English, and the lexical limitation is no obstacle to their making calculations involving larger numbers.[6] Furthermore, the Mundurucu use logarithmic mapping of numbers to assess scales, a point cited as possible evidence for the notion that this kind of numbering is innate, whereas the linear mode has to be acquired by study.[7][8]

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Munduruku: Introduction." Povos Indígenous no Brasil. (retrieved 22 June 2011)

- 1 2 3 4 "Munduruku: Name and Language." Povos Indígenous no Brasil. (retrieved 22 June 2011)

- ↑ ISA.

- ↑ Fearnside 2015, p. 426.

- ↑ Farias 2016.

- ↑ Rosemary Varley, 'Substance or Scafforld? The role of language in thought', in Victoria Joffe, Madeleine Cruice, Shula Chiat (eds.)Language Disorders in Children and Adults: New Issues in Research and Practice, Wiley-Blackwell, 2008 pp.20-38, p.27.

- ↑ Bossomaier 2014, p. 56.

- ↑ Varshney & Sun 2015, p. 64.

Sources

- Bossomaier, Terry (2014). "Language Networks". In Stocker, Robert; Bossomaier, Terry. Networks in Society: Links and Language. CRC Press. pp. 49–79. ISBN 978-9-814-36482-9.

- Farias, Elaíze (19 April 2016), "Funai reconhece território tradicional Sawré Muybu dos Munduruku" [Funai recognises the traditional Sawré Muybu territory of the Munduruku], Amazônia Real (in Portuguese), retrieved 16 February 2017

- Fearnside, Philip M. (2015), "Amazon dams and waterways: Brazil's Tapajo´s Basin plans" (PDF), AMBIO, 44: 426, doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0642-z, PMC 4510327, PMID 25794814, retrieved 13 February 2017

- Munduruku: Localização e população, ISA: Instituto Socioambeintal, retrieved 14 February 2017

- Varshney, Lav R.; Sun, John Z. (2015). "Why Do We Perceive Logarithmically?". In Pitici, Mircea. The Best Writing on Mathematics 2014. Princeton University Press. pp. 64–73. ISBN 978-0-691-16417-5.

External links

- "Cognition and arithmetics capability: what the Mundurucus Indians can teach us", CNRS Press release October 2004

- Amazon Children "Spontaneously" Understand Geometry National Geographic News, January 2006

- "Mastering the Geometry of the Jungle", New York Times, 24 June 2006

- "Intuitions of number-space in Amazonian Indigenous groups" CEA Press release, June 2008.

- Pica, P; Lecomte, A (2008). "Theoretical implications of the study of Numbers and Numerals in Mundurucu". Philosophical Psychology. 21: 4. doi:10.1080/09515080802285461.

- Pica, P, C Lemer, V Izard & Dehaene, S. (2004), "Exact and approximate arithmetic in an Amazonian Indigene Group" Science, 306, pp. 499–503.

- Dehaene, S., Izard, V., Spelke, E & Pica, P (2008), "Log or linear Distinct Intuitions of the number scale in Western and Amazonian Indigene Culture" Science 320, 5880, 1217–20

- Wuy Jugu artwork, National Museum of the American Indian