Wieliczka Salt Mine

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

St. Kinga's Chapel, deep in the Wieliczka salt mine | |

| Location | Wieliczka, Kraków County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland |

| Part of | Wieliczka and Bochnia Royal Salt Mines |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 32ter |

| Inscription | 1978 (2nd Session) |

| Extensions | 2008, 2013 |

| Endangered | 1989–1998[1] |

| Area | 970 ha (2,400 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 250 ha (620 acres) |

| Website |

www |

| Coordinates | 49°58′45″N 20°3′50″E / 49.97917°N 20.06389°ECoordinates: 49°58′45″N 20°3′50″E / 49.97917°N 20.06389°E |

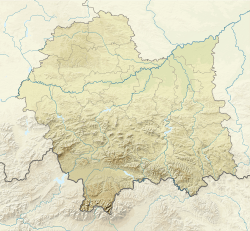

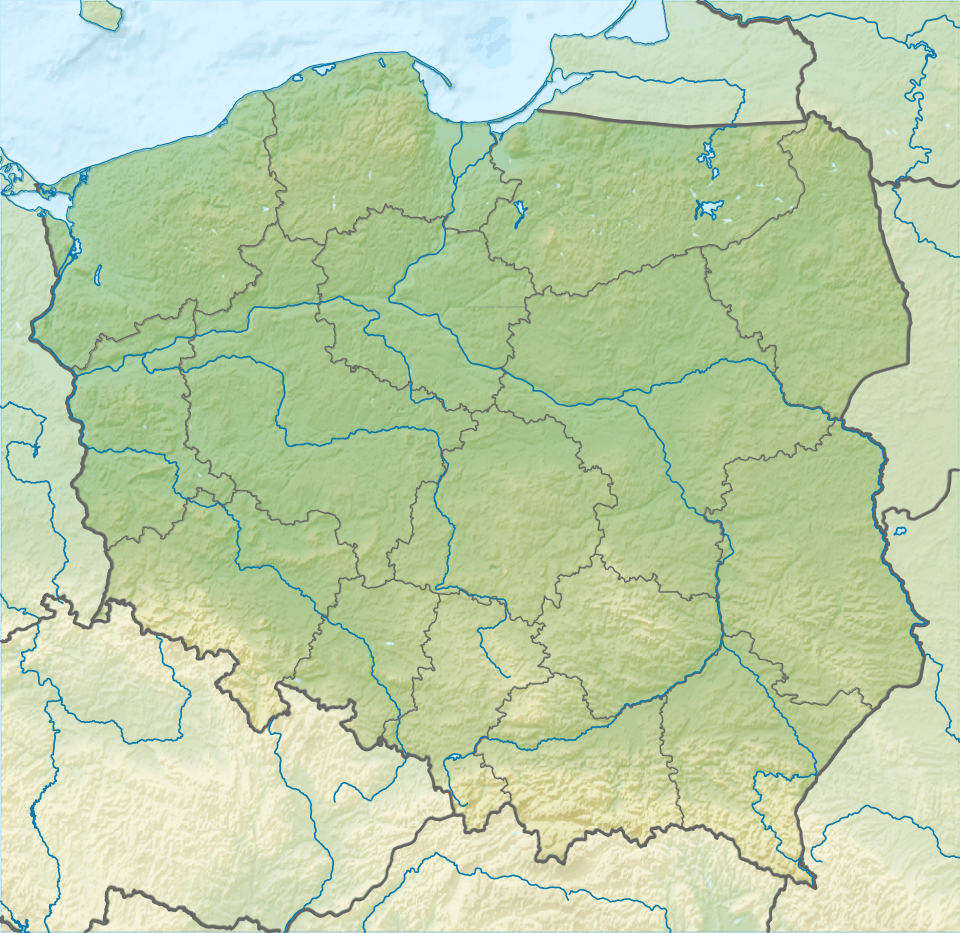

Location of Wieliczka Salt Mine in Lesser Poland Voivodeship  Wieliczka Salt Mine (Poland) | |

The Wieliczka Salt Mine (Polish: Kopalnia soli Wieliczka), located in the town of Wieliczka in southern Poland, lies within the Kraków metropolitan area. Opened in the 13th century, the mine produced table salt continuously until 2007, as one of the world's oldest salt mines in operation. Throughout, the royal mine was run by the Żupy krakowskie Salt Mines company.[2][3]

Commercial mining was discontinued in 1996, because of salt prices going down and also mine flooding.[2][3] The mine is currently one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomniki historii), whose attractions include dozens of statues and four chapels carved out of the rock salt by the miners, as well as supplemental carvings made by contemporary artists.

History

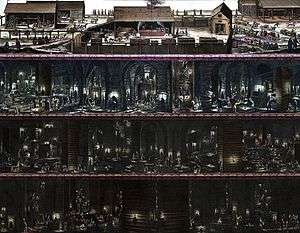

The Wieliczka salt mine reaches a depth of 327 meters and is over 287 kilometres (178 mi) long. The rock salt is naturally grey in various shades, resembling unpolished granite rather than the white or crystalline look that many visitors may expect. In the 13th century, rock salt was discovered in Wieliczka and the first shafts were dug.[4] The construction of the Saltworks Castle in Wieliczka (the central building – “The House within the Saltworks”) – head office of the mine’s board since medieval times till 1945. The Saltworks Castle was built in the late 13th to early 14th century. Wieliczka is now the location of the Kraków Saltworks Museum. Many shafts were dug throughout the time the mine was in operation.[5] Different technology was added such as the Hungarian-type horse treadmill and Saxon treadmills to haul the salt to the top of the surface.[5] During World War II, the shafts were used by the occupying Germans as an ad hoc facility for various war-related industries. The mine features an underground lake; and the new exhibits on the history of salt mining, as well as a 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) touring route (less than 2% of the length of the mine's passages) that includes historic statues and mythical figures carved out of rock salt in distant past. More recent sculptures have been fashioned by contemporary artists.

The Wieliczka mine is often referred to as "the Underground Salt Cathedral of Poland". In 1978 it was placed on the original UNESCO list of the World Heritage Sites.[6] Even the crystals of the chandeliers are made from rock salt that has been dissolved and reconstituted to achieve a clear, glass-like appearance. It also houses a private rehabilitation and wellness complex.

There is a legend about Princess Kinga, associated with the Wieliczka mine. The Hungarian princess was about to be married to Bolesław V the Chaste, the Prince of Kraków. As part of her dowry, she asked her father, Béla IV of Hungary, for a lump of salt, since salt was prizeworthy in Poland. Her father King Béla took her to a salt mine in Máramaros. She threw her engagement ring from Bolesław in one of the shafts before leaving for Poland. On arriving in Kraków, she asked the miners to dig a deep pit until they come upon a rock. The people found a lump of salt in there and when they split it in two, discovered the princess's ring. Kinga had thus become the patron saint of salt miners in and around the Polish capital.[7]

During the Nazi occupation, several thousand Jews were transported from the forced labour camps in Plaszow and Mielec to the Wieliczka mine to work in the underground armament factory set up by the Germans. However, manufacturing never began as the Soviet offensive was nearing. Some of the machines and equipment were disassembled, including an electrical hoisting machine from the Regis Shaft, and transported to Liebenau in the Sudetes mountains. Part of the equipment was returned after the war, in autumn 1945. The Jews were transported to factories in the Czech Republic and Austria.[8]

The mine is one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomniki historii), as designated in the first round, 16 September 1994. Its listing is maintained by the National Heritage Board of Poland. In 2010 it was successfully proposed that the nearby historic Bochnia Salt Mine (Poland's oldest salt mine) be added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage sites. The two sister salt mines now appear together in the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites as the "Wieliczka and Bochnia Royal Salt Mines".[9] In 2013 the UNESCO World Heritage Site was expanded by the addition of the Żupny Castle.

Tourism

The mine is currently one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomniki historii), whose attractions include dozens of statues and four chapels carved out of the rock salt by the miners. The older sculptures have been supplemented with new carvings made by contemporary artists. About 1.2 million people visit the Wieliczka Salt Mine annually.[2]

Notable visitors to this site have included Nicolaus Copernicus, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, Fryderyk Chopin, Dmitri Mendeleyev, Bolesław Prus,[10] Ignacy Paderewski, Robert Baden-Powell, Jacob Bronowski (who filmed segments of The Ascent of Man in the mine), the von Unrug family (a prominent Polish-German royal family), Karol Wojtyła (later, Pope John Paul II), former U.S. President Bill Clinton, and many others.

There is a chapel, and a reception room that is used for private functions, including weddings. A chamber has walls carved by miners to resemble wood, as in wooden churches built in early centuries. A wooden staircase provides access to the mine's 64-metre (210-foot) level. A 3-kilometre (1.9-mile) tour features corridors, chapels, statues, and underground lake, 135 metres (443 ft) underground. An elevator (lift) returns visitors to the surface; the elevator holds 36 persons (nine per car) and takes some 30 seconds to make the trip.

In Culture

The earliest writings about the Wieliczka Salt Mine include a description by Adam Schröter: Salinarum Vieliciensium incunda ac vera descriptio. Carmine elegiaco... (1553); augmented edition: Regni Poloniae Salinarum Vieliciensium descriptio. Carmine elegiaco... (1564).[11]

The Polish journalist and novelist Bolesław Prus described his 1878 visit to the salt mine in a remarkable series of three articles, "Kartki z podróży (Wieliczka)" ["Travel Notes (Wieliczka)"], in Kurier Warszawski (The Warsaw Courier), 1878, nos. 36–38.[12]

The great Prus scholar Zygmunt Szweykowski writes: "The power of the Labyrinth scenes [in Prus' 1895 historical novel, Pharaoh] stems, among other things, from the fact that they echo Prus' own experiences when visiting Wieliczka."[10]

The Wieliczka Salt Mine indeed helped inspire Pharaoh.[13] Prus combined his powerful impressions of the salt mine with the description of the ancient Egyptian Labyrinth, in Book II of Herodotus' Histories, to produce the remarkable scenes found in chapters 56 and 63 of his novel.[14]

In 1995, Preisner's Music, a compilation of film music by Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner, was recorded by Sinfonia Varsovia in the Wieliczka mine's chapel. The chapel is often said to have the best acoustics in Europe.[15]

In the Australia television series Spellbinder: Land of the Dragon Lord, the mines were used as the Land of the Moloch.

Virtual tour

| Wieliczka Salt Mine | |||

with headframe |

into the rock salt[3] |

carved into rock-salt wall |

Old corridor |

_(2).jpg) Pope John Paul II |

in the museum |

St. Kinga's Shaft |

St. Kinga's Chapel |

Sister caves

See also

- Pharaoh: the Wieliczka Salt Mine inspired scenes in the historical novel by Bolesław Prus

- Bochnia Salt Mine, in southern Poland

- Chełm Chalk Tunnels, in Poland

- Kłodawa Salt Mine, in central Poland

- Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, Colombia

- Frasassi Caves, Italy

- Grand Roc, France

- Kartchner Caverns State Park, United States

Notes

- ↑ World Heritage Committee Removes Old City of Dubrovnik and Wieliczka Salt Mine from its List of Endangered Sites at UNESCO website

- 1 2 3 "Wieliczka – The Salt of the Earth" at the WieliczkaSaltMine.net. (in English) (in Polish).

- 1 2 3 Ancient salt-works. Wieliczka see: carving by Jozef Markowski, late 19th century. (Internet Archive). Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Goldensubmarine.com. "Kopalnia Soli Wieliczka". www.wieliczka-saltmine.com. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- 1 2 Goldensubmarine.com. "Kopalnia Soli Wieliczka". www.wieliczka-saltmine.com. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Wieliczka Salt Mine - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "History of Wieliczka Salt Mine". Poland For Visitors Travel Guide. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ "History - "Wieliczka" Salt Mine - tourist attractions of Malopolska". Wieliczka-saltmine.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ Wieliczka and Bochnia Royal Salt Mines. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- 1 2 Zygmunt Szweykowski, Twórczość Bolesława Prusa (The Works of Bolesław Prus), second edition, Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1972, p. 451, note 21.

- ↑ Marek Żukow-Karczewski, "Pięknem urzeczeni (trzy zapomniane relacje)" ("Enchanted by beauty: three forgotten relations"), Aura 1, 1998, pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Reprinted in Bolesław Prus, Wczoraj–dziś–jutro: wybór felietonów (Yesterday–Today–Tomorrow: a Selection of Newspaper Columns, selected, edited, and with foreword and notes, by Zygmunt Szweykowski), Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1973, pp. 34–49.

- ↑ Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' Pharaoh and the Wieliczka Salt Mine," The Polish Review, 1997, no. 3, pp. 349–55.

- ↑ Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' Pharaoh: the Creation of a Historical Novel", The Polish Review, vol. XXXIX, no. 1, 1994, p. 47.

- ↑ Zbigniew Preisner, "Preisner's Music", Virgin France, 1995.

- ↑ Grotte Gemellate. Consorzio frasassi. (Internet Archive)

References

- Jerzy Grzesiowski, Wieliczka: kopalnia, muzeum, zamek (Wieliczka: the Mine, the Museum, the Castle), 2nd ed., updated and augmented, Warsaw, Sport i Turystyka, 1987, ISBN 83-217-2637-2.

- Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' Pharaoh and the Wieliczka Salt Mine," The Polish Review, 1997, no. 3, pp. 349–55.

- Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' Pharaoh: the Creation of a Historical Novel", The Polish Review, vol. XXXIX, no. 1, 1994, pp. 45–50.

- Bolesław Prus, Wczoraj–dziś–jutro: wybór felietonów (Yesterday–Today–Tomorrow: a Selection of Newspaper Columns, selected, edited, and with foreword and notes, by Zygmunt Szweykowski), Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1973, pp. 34–49.

- Zygmunt Szweykowski, Twórczość Bolesława Prusa (The Works of Bolesław Prus), second edition, Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1972.

- Marek Żukow-Karczewski, Pięknem urzeczeni (trzy zapomniane relacje) / Enchanted by beauty (three forgotten relations), "Aura" - A Monthly for the Protection and Shaping of Human Environment, no. 1, 1998, p. 17-19.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wieliczka salt mine. |

- Wieliczka Salt Mine - Official Website

- Wieliczka The salt of the Earth/

- Video tour of mine

- Cracow Salt-Works Museum in Wieliczka (plan of mine)

- Wieliczka Salt Mine near Kraków in Poland

- Wieliczka Salt Mine Tour

- Air Pollution Intrusion into the Wieliczka Salt Mine

- "A Piece of Salt that Weighs 200 Tons" fallen from Wieliczka chamber roof in 1916; Popular Science monthly, Feb 1916, page 179. Scanned by Google Books.