Visconti of Milan

| Visconti | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Coat of arms of the Visconti of Milan | |

| Ethnicity | Italian |

| Founded | 1075 |

| Founder | Ariprando Visconti |

| Final ruler | Filippo Maria Visconti |

| Titles |

Lord of Milan (1277–1395) Duke of Milan (1395–1447) |

| Motto |

Vipereos mores non violabo (Latin for "I will not violate the customs of the serpent") |

| Cadet branches | Visconti di Modrone |

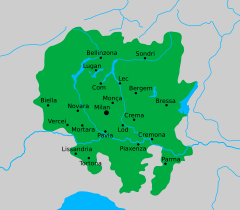

Visconti is the family name of important Italian noble dynasties of the Middle Ages. The Visconti of Milan rose to power in their city, where they ruled from 1277 to 1447, initially as Lords then as Dukes and where several collateral branches still exist. The effective founder of the Visconti lordship of Milan was Ottone, who wrested control of the city from the rival Della Torre family in 1277.[1]

Origins

In the second half of the 11th century, Ariprando Visconti and his son Ottone were the first family members to obtain the title of viscount, which then became hereditary throughout the male descent.[2][3] The primary sources show the first evidence of "Ariprandus et Otto Vicecomes" in 1075. In the following years, Ottone is shown in the proximity of the sovereigns of the Salian dynasty, Henry IV and his son Conrad. This relationship is confirmed by the circumstances of his death, which occurred in Rome in 1111, when he was slaughtered after an attempt to defend Henry V from an assault.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2][4] In the first documents where they appear, Ottone and his offspring declared to follow the Lombard law and acted in connection with other Milanese families of the noble upper class (capitanei). A relationship with the Litta, a Milanese vavasour family subordinate to the Visconti in the feudal hierarchy, is also documented.[5] These circumstances make evident their participation to the Milanese society in the years before 1075 and ultimately their Lombard origin.

In 1134, Guido Visconti, son of Ottone, received from the abbot of St. Gallen the investiture of the court of Massino, a strategic location on the hills above Lake Maggiore, near Arona,[6] where another family member was present in the second half of the 12th century as a guardian of the local archiepiscopal fortress. In 1142, the investiture was confirmed by the King Conrad III, in a diploma released to Guido in Ulm.[7] Another royal diploma, issued by Conrad III in 1142 as well, attests the entitlement of the Visconti to the fodrum in Albusciago and Besnate.[8] On the basis of a document from the year 1157, the Visconti were considered holders of the captaincy of Marliano (today Mariano Comense) since the time of the archbishop Landulf;[9] however, the available documentation cannot infer such conclusion.[10]

A second Ottone, son of Guido, is attested in the documentary sources between the years 1134 and 1192. The primary role of Ottone in the political life of the Milanese commune emerges in the period of the confrontation with Frederick Barbarossa: his name is the first to be cited, March 1, 1162, in the group of Milanese leaders surrendering to the emperor after the capitulation of the city that took place in the previous weeks.[11][12] A member of the following generation, Ariprando was bishop of Vercelli between 1208 and 1213, when he played also the role of Papal legate for Innocent III. An attempt to have him elected archbishop of Milan failed in 1212 amidst growing tensions between opposite factions inside the city. His death, in 1213, was probably caused by poisoning.[13]

The family dispersed into several branches, some of which were entrusted fiefs far off from the Lombard metropolis; the one which gave the Medieval lords of Milan is said to be descended from Uberto, who died in the first half of 13th century. The members of the other branches added frequently to their surname the name of the place where they chose to live and where a castle was available for their residence. The first of such cases were the Visconti of Massino, the Visconti of Invorio and the Visconti of Oleggio Castello.[14] In these localities the castle (Massino), its remains (Invorio) or a later reconstruction of the initial building (Oleggio Castello) are still today visible.

Lords and Dukes of Milan

The Visconti ruled Milan until the early Renaissance, first as Lords, then, from 1395, with the mighty Gian Galeazzo who endeavored to unify Northern Italy and Tuscany, as Dukes. Visconti rule in Milan ended with the death of Filippo Maria Visconti in 1447. He was succeeded by a short-lived republic and then by his son-in-law Francesco I Sforza, who established the reign of the House of Sforza.[15][16]

Rise to the lordship

With the death of Frederick II in 1250 and the ceasing of the war of the Lombard League against him, which itself was a reason for the Milanese commune to be united in its defence, a period of conflicts between rivaling factions began inside the city. The Della Torre family progressively acquired power in Milan after 1240, when Pagano Della Torre assumed the leadership of the Credenza di Sant'Ambrogio, a political party with a popular base. This allowed them to have a role in the tax collection of the commune (estimo), which was essential to finance the war against Frederick II while affecting the great landowners. In 1247 Pagano was succeeded by his nephew Martino Della Torre. To underline the preeminence of his position, the new role of Senior of the Credenza (Anziano della Credenza) was created. In this position the Della Torre began to be confronted with the Milanese noble families organized in their own political party, the Societas Capitaneorum et Valvassorum, having the Visconti among the most prominent figures. After a period of unrest between the opposite parties, in 1258 the so called Sant'Ambrogio Peace was signed among the parties, strengthening the position of La Credenza and La Motta (a second political party with popular tendencies).[17][18]

The peace was undermined by new events in favour of the Della Torre. At the end of 1259, Oberto Pallavicino, a former partisan of Frederick II who got closer to the Guelph positions of the Della Torre, was appointed by the Milanese commune for five years in the role of General Captain of the People. Pallavicino's position in Milan was greatly enhanced by the victory he obtained in the Battle of Cassano on 16 September 1259, against Ezzelino da Romano, formerly his ally on the Ghibelline side in the war against Milan, the Lombard League and the Papacy. In Ezzelino the noble expelled from Milan during the clashes preceding the Sant'Ambrogio Peace placed their hopes to get back in the city to their old power. In 1264, when Pallavicino left his office (preparing another change of alliance), Martino Della Torre remained the sole ruler of Milan and de facto its Lord.[19][18][20]

A decisive event in the confrontation between the Della Torre and the Visconti factions was the appointment of Ottone Visconti to archbishop of Milan in 1262. Ottone was preferred by Pope Urban IV to Raimondo, another candidate member of the Della Torre family. Prevented from assuming his office and forced by the opposite faction to remain outside the city, Ottone tried to settle in Arona, at the border of the Milanese archdiocese. At the end of 1263, Della Torre forces with the support of Oberto Pallavicino dislodged him from Arona. Ottone sought refuge in central Italy near the pope. The Della Torre party under the guidance of Filippo Della Torre, brother of Martino and his successor after 1263, took advantage also of the favour of Charles of Anjou. Milan forged an alliance with him and with other northern Italian cities (Lega Guelfa) to fight the Hohenstaufen rule in southern Italy. Francesco Della Torre led the Milanese expedition in southern Italy, which ended in 1266 with the allied victory against Manfred of Sicily in the Battle of Benevento. Charles of Anjou became the new King of Sicily, having also an indirect rule (exercised through the Della Torre) on Milan.[21]

Trying to take advantage from the favourable moment, in 1266 the Della Torre made an attempt to advocate their cause against the Visconti in a concistory held by Pope Clement IV in Viterbo and attended by the archbishop Ottone. Despite the presence of a delegate of Charles of Anjou the decision of the pope was in favour of Ottone. An attempt was then made by the Pope to appease the Milanese factions by means of an oath of allegiance demanded to the Milanese population. Part of it was the acceptance of Ottone as archbishop. The events however were changed again by new circumstances in favour of the Della Torre. At the end of 1266 in Germany was taken the decision to support Conradin, the last member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, in an attempt to recovery the domains in southern Italy lost after the defeat of Benevento and the death of Manfred of Sicily. This reinstated again the Della Torre in their position of leaders of the Lega Guelfa. Moreover, in 1268, Clement IV died, initiating a period of papal vacancy that left without practical consequences the dispositions in favour of Ottone.[22]

After the definitive end of the Hohenstaufen threat (Conradin was defeated and executed in Naples in 1268), the confrontation between the two Milanese factions assumed more and more a military connotation. A leading figure on the Visconti side was Simone Orelli da Locarno, whose military ability became legendary during the wars against Fredrick II. Notwithstanding this, being in favour of the Visconti, he was arrested in 1263 and jailed in Milan. In 1276 he was freed in the context of a compromise between the two factions about Como and after his promise of not acting against the Della Torre. He joined altogether the Visconti army assuming the role of General Captain. The Visconti forces took progressively advantage in the area of Lake Maggiore. In 1276 Tebaldo Visconti, nephew of Ottone, was captured with other leading figures of the Visconti forces. Brought to Gallarate, they were executed by beheading. The Visconti eventually defeated the Della Torre army in the decisive Battle of Desio on 27 January 1277, opening the way for Ottone to enter in Milan.[20] Napoleone, son of Pagano, was arrested with other Della Torre family members. He died in jail few months later. These events are generally considered to mark the foundation of the Visconti lordship on Milan.[23]

Ottone initially granted power in Milan to Simone Orelli, appointing him Captain of the People. In 1287, he transferred this role to his grandnephew Matteo Visconti (the son of Tebaldo executed in 1277), who one year later obtained also the title of Imperial vicar from the emperor Rudolf of Habsburg. Ottone died in 1295, leaving Matteo Lord of Milan. In 1302, the Della Torre took again the power, forcing Matteo to leave the city. After an intervention of Henry VII, appeasing the dispute between the two families, the lordship of the Visconti on Milan was definitely restored in 1311.[24][18][20]

Visconti rulers of Milan[15]

- Ottone Visconti, Archbishop of Milan (1277–1294)

- Matteo I Visconti (1294–1302; 1311–1322)

- Galeazzo I Visconti (1322–1327)

- Azzone Visconti (1329–1339)

- Luchino I Visconti (1339–1349)

- Giovanni Visconti, Archbishop of Milan (1349–1354)

- Bernabò Visconti (1354–1385)

- Galeazzo II Visconti (1354–1378)

- Matteo II Visconti (1354–1355)

- Gian Galeazzo Visconti (1378–1402) {son of Galeazzo II, 1st Duke of Milan from 1395}

- Giovanni Maria Visconti (1402–1412)

- Filippo Maria Visconti (1412–1447)

Family tree

|

Uberto Visconti [1][15][16][25] *? †1248 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Azzone[lower-alpha 3] *? †? |

Andreotto *? †? |

Ottone[lower-alpha 4] *1207 †1295 |

Obizzo[lower-alpha 5] *? †? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Teobaldo *1230 †1276 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Matteo I il Magno[lower-alpha 6] *1250 †1322 |

Uberto il Pico *1280? †1315 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Galeazzo[lower-alpha 7] *1277 †1328 |

Marco *? †1329 |

Luchino[lower-alpha 8] *1287 †1349 |

Stefano *1288 †1327 |

Giovanni[lower-alpha 9] *1290 †1354 |

Vercellino[lower-alpha 10] *? †? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Azzone[lower-alpha 11] *1302 †1339 |

Luchino *? †1399 |

Matteo II[lower-alpha 12] *1319 †1355 |

Galeazzo II[lower-alpha 13] *1320? †1378 |

Bernabò[lower-alpha 14] *1323 †1385 |

Giovanni[lower-alpha 15] *? †? |

Line of Visconti of Modrone | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gian Galeazzo[lower-alpha 16] *1351 †1402 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Giovanni Maria[lower-alpha 17] *1388 †1412 |

Filippo Maria[lower-alpha 18] *1392 †1447 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bianca Maria[lower-alpha 19] *1425 †1468 |

Francesco Sforza *1401 †1466 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Sforza | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Visconti di Modrone

From Uberto Visconti (c. 1280–1315), brother of Matteo I Visconti, came the lateral branch of Dukes of Modrone. To this family belonged Luchino Visconti di Modrone, one of the most prominent film directors of Italian neorealist cinema.

Some members of this branch were:

- Uberto Visconti di Modrone (1871-1923), entrepreneur

- Marcello Visconti di Modrone (1898-1964), son of Uberto

- Guido Visconti di Modrone (military) (1901-1942)

- Luchino Visconti di Modrone (1906-1976), director

- Galeazzo Visconti di Modrone (1918-1976)

- Eriprando Visconti di Modrone (1932-1995), director

- Violante Visconti di Modrone, set decorator in the Academy awards nominated 2017 Call Me by Your Name (film)[26][27]

Other members

- Federico Visconti (1617–1693), Cardinal and Archbishop of Milan from 1681 to 1693.

- Filippo Maria Visconti (archbishop) (1721-1801), Archbishop of Milan from 1784 to 1801.

- Gaspare Visconti, Archbishop of Milan from 1584 to 1595.

- Roberto Visconti, Archbishop of Milan from 1354 to 1361.

- Valentina Visconti, elder daughter of Giangaleazzo Visconti, Duchess of Orléans and grandmother of King Louis XII of France, who conquered Milan as her heir

Notes

- ↑ Landulfi de Sancto Paolo Historia Mediolanensis, p. 31, rr. 33-35: "Otto autem Mediolanensis vicecomes cum multis pugnatoribus eiusdem regis in ipsa strage coruit in mortem, amarissimam hominibus diligentibus civitatem Mediolanensium et ecclesiam."

- ↑ Leonis Marsicani et Petri Diaconi Chronica Monasterii Casinensis, p. 780, rr. 37-40: "Hoc ubi Otto comes Mediolanensis perspexit, pro imperatore se ad mortem obiciens, equum suum contradidit; nec mora, a Romanis captus, et in Urbem inductus, minutatim concisus est, eiusque carnes in platea canibus devorandae relictae."

- ↑ Bishop of Ventimiglia (1251 - 1262).

- ↑ Archbishop of Milan (1262), lord of Milan (1277-78) and (1282-85).

- ↑ Console di giustizia in Milan (1236)).

- ↑ Capitano del popolo of Milan (1287-1298), lord of Milan (1287-1302) e (1311-1322).

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1322-1327).

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1339-1349).

- ↑ Archbishop of Milan (1339), lord of Milan (1339-1354), lord of Bologna and Genoa (1331-1354).

- ↑ Podestà of Vercelli (1317) and Novara (1318-1320). Line of the Visconti di Modrone (marquesses of Vimodrone 1694, later Dukes of Vimodrone 1813) whose members include the film directors Luchino Visconti and Eriprando Visconti.

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1329-1339).

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1354-1355).

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1354-1378).

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1354-1385).

- ↑ Presumed. Lord of Bologna (1355-1360).

- ↑ Lord of Milan (1378-1395) and Duke of Milan (1395-1402).

- ↑ Duke of Milan (1402-1412).

- ↑ Duke of Milan (1412-1447).

- ↑ Illegitimate, by Agnese del Maino; in 1441 married to Francesco I Sforza, later duke of Milan.

References

- 1 2 Tolfo, Maria Grazia; Colussi, Paolo (February 7, 2006). "Storia di Milano: I Visconti" [History of Milan: The Visconti]. Storia di Milano (in Italian). Milano. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ↑ Biscaro (1911), p. 20-24

- ↑ Filippini (2014), p. 33-42

- ↑ Filippini (2014), pp. 44-45, 83

- ↑ Keller, Hagen (1979). Adelsherrschaft und städtische Gesellschaft in Oberitalien: 9. bis 12. Jahrhundert. Bibliotek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom (in German). 52. p. 207.

- ↑ Conradi III. et filii eius Heinrici Diplomata, doc. 21

- ↑ Filippini (2014), p. 58-65

- ↑ Conradi III. et filii eius Heinrici Diplomata, doc. 20

- ↑ Biscaro (1911), p. 28

- ↑ Filippini (2014), p. 73-74

- ↑ Filippini (2014), p. 100-101

- ↑ Das Geschichtswerk des Otto Morena und seiner Fortsetzer über die Taten Friedrichs I. in der Lombardei, p. 152

- ↑ Filippini (2014), p. 105-113

- ↑ Filippini (2014), p. 62-63

- 1 2 3 Hale, John Rigby (1981). A concise encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 338–341, 352. OCLC 636355191.

- 1 2 Williams, George L. (1998). "Two: The Papal Families at the Close of the Middle Ages, 1200-1471". Papal genealogy: The families and descendants of the popes. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-0-7864-0315-8. OCLC 301275208. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ↑ Cognasso (2014), p. 33-45

- 1 2 3 Menant, François (2005). L’Italie des communes (1100-1350) (in French). Édition Belin. pp. 67, 111–112, 117–118.

- ↑ Cognasso (2016), p. 45-51

- 1 2 3 Jones, Philip (2004). The Italia City-State. From Commune to Signoria. Oxford University Press. pp. 520–521, 603, 619.

- ↑ Cognasso (2014), p. 56-62

- ↑ Cognasso (2014), p. 64-67

- ↑ Cognasso (2014), p. 67-71

- ↑ Cognasso (2014), p. 87-100, 109-124

- ↑ Visconti, Alessandro (1952). Storia di Milano (in Italian) (2 ed.). p. 275.

- ↑ "Violante Visconti di Modrone - Vogue.it". vogue.it. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Story Behind the Italian Villa in Call Me By Your Name - Architectural Digest". architecturaldigest.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

Primary sources

- Conradi III. et filii eius Heinrici Diplomata, edited by Friedrich Hausmann. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Diplomata regum et imperatorum Germaniae (in German). 9. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: MGH. 1969.

- Landulfi de Sancto Paolo Historia Mediolanensis, edited by Ludwig Bethmann and Philipp Jaffé. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores (in folio) (in Latin). 20. Hannover: MGH. 1868. pp. 17–49.

- Leonis Marsicani et Petri Diaconi Chronica Monasterii Casinensis, edited by Wilhelm Wattenbach. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores (in folio) (in Latin). 7. Hannover: MGH. 1846. pp. 727–844.

- Das Geschichtswerk des Otto Morena und seiner Fortsetzer über die Taten Friedrichs I. in der Lombardei, edited by Ferdinand Güterbock. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, Nova series (SS rer. Germ. N.S.) (in German). 7. Berlin: MGH. 1930.

Secondary sources

- Biscaro, Gerolamo (1911), "I maggiori dei Visconti, signori di Milano", Archivio Storico Lombardo, serie 4 (in Italian), 16: 5–76

- Cognasso, Francesco (2014). I Visconti. Storia di una famiglia (in Italian) (2 ed.). Odaya. ISBN 9788862883061.

- Filippini, Ambrogio (2014). I Visconti di Milano nei secoli XI e XII. Indagini tra le fonti (in Italian). Tangram Edizioni Scientifiche. ISBN 9788864580968.