Vinegar

Vinegar is an aqueous solution of acetic acid and trace chemicals that may include flavorings. Vinegar typically contains 5–20% by volume acetic acid. Usually the acetic acid is produced by the fermentation of ethanol or sugars by acetic acid bacteria.[1] Vinegar is now mainly used as a cooking ingredient, or in pickling. There are many types of vinegar, depending upon the source materials.

As the most easily manufactured mild acid, it has historically had a wide variety of industrial, medical, and domestic uses. Some of these are still commonly practiced, such as its use as a household cleaner.

Production

Commercial vinegar is produced either by a fast or a slow fermentation process. In general, slow methods are used in traditional vinegars, where fermentation proceeds over the course of a few months to a year. The longer fermentation period allows for the accumulation of a nontoxic slime composed of acetic acid bacteria.

Fast methods add mother of vinegar (bacterial culture) to the source liquid before adding air to oxygenate and promote the fastest fermentation. In fast production processes, vinegar may be produced in one to three days.

Chemistry

The conversion of ethanol (CH3CH2OH) and oxygen (O2) to acetic acid (CH3COOH) takes place by the following reaction:[2]

- CH3CH2OH + O2 → CH3COOH + H2O

Polyphenols

Vinegar contains numerous flavonoids, phenolic acids, and aldehydes,[3] which vary in content depending on the source material used to make the vinegar, such as orange peel or various fruit juice concentrates.[4][5]

Etymology

The word vinegar arrived in Middle English from Old French vyn egre, which in turn derives from Latin vinum (wine) + acer (sour).[6]

History

Vinegar has been made and used by people for thousands of years.[7] Traces of it have been found in Egyptian urns from around 3000 BC.

Varieties

Source materials for making vinegar are varied, including different fruits, grains, alcoholic beverages or other fermentable materials.

Fruit

Fruit vinegars are made from fruit wines, usually without any additional flavoring. Common flavors of fruit vinegar include apple, blackcurrant, raspberry, quince, and tomato. Typically, the flavors of the original fruits remain in the final product. Most fruit vinegars are produced in Europe, where there is a growing market for high-price vinegars made solely from specific fruits (as opposed to non-fruit vinegars that are infused with fruits or fruit flavors).[8] Several varieties, however, also are produced in Asia. Persimmon vinegar, called gam sikcho, is popular in South Korea. Jujube vinegar, called zaocu or hongzaocu, and wolfberry vinegar are produced in China.

Apple cider vinegar is made from cider or apple must, and has a brownish-gold color. It is sometimes sold unfiltered and unpasteurized with the mother of vinegar present, as a natural product. It can be diluted with fruit juice or water or sweetened (usually with honey) for consumption.[9]

A byproduct of commercial kiwifruit growing is a large amount of waste in the form of misshapen or otherwise-rejected fruit (which may constitute up to 30 percent of the crop) and kiwifruit pomace, the presscake residue left after kiwifruit juice manufacture. One of the uses for this waste is the production of kiwifruit vinegar, produced commercially in New Zealand [10] since at least the early 1990s, and in China in 2008.[11]

Coconut vinegar, made from fermented coconut water or sap, is used extensively in Southeast Asian cuisine (notably the Philippines), as well as in some cuisines of India and Sri Lanka, especially Goan cuisine. A cloudy white liquid, it has a particularly sharp, acidic taste with a slightly yeasty note. Vinegar made from dates is a traditional product of the Middle East.[12][13]

Pomegranate vinegar (Hebrew: חומץ רימונים) is used widely in Israel as a dress for salad but also in meat stew and in dips.[14] Vinegar made from raisins, called khall ʻinab (Arabic: خل عنب "grape vinegar") is used in cuisines of the Middle East, and is produced there. It is cloudy and medium brown in color, with a mild flavor.

Palm vinegar, made from the fermented sap from flower clusters of the nipa palm (also called attap palm), is used most often in the Philippines, where it is produced, and where it is called sukang paombong. It has a citrusy flavor note to it[15] and imparts a distinctly musky aroma.

Balsamic

Balsamic vinegar is an aromatic aged vinegar produced in the Modena and Reggio Emilia provinces of Italy. The original product—Traditional Balsamic Vinegar—is made from the concentrated juice, or must, of white Trebbiano grapes. It is very dark brown, rich, sweet, and complex, with the finest grades being aged in successive casks made variously of oak, mulberry, chestnut, cherry, juniper, and ash wood. Originally a costly product available to only the Italian upper classes, traditional balsamic vinegar is marked "tradizionale" or "DOC" to denote its Protected Designation of Origin status, and is aged for 12 to 25 years. A cheaper non-DOC commercial form described as "aceto balsamico di Modena" (balsamic vinegar of Modena)[16] became widely known and available around the world in the late 20th century, typically made with concentrated grape juice mixed with a strong vinegar, then coloured and slightly sweetened with caramel and sugar.

Regardless of how it is produced, balsamic vinegar must be made from a grape product. It contains no balsam fruit. A high acidity level is somewhat hidden by the sweetness of the other ingredients, making it very mellow.

Cane

Vinegar made from sugarcane juice is most popular in the Philippines, in particular in the northern Ilocos Region (where it is called Sukang Iloko), although it also is produced in France and the United States. It ranges from dark yellow to golden brown in color, and has a mellow flavor, similar in some respects to rice vinegar, though with a somewhat "fresher" taste. Because it contains no residual sugar, it is no sweeter than any other vinegar. In the Philippines it often is labeled as sukang maasim (Tagalog for "sour vinegar").

Cane vinegars from Ilocos are made in two different ways. One way is to simply place sugar cane juice in large jars; it becomes sour by the direct action of bacteria on the sugar. The other way is through fermentation to produce a local wine known as basi. Low-quality basi is then allowed to undergo acetic acid fermentation that converts alcohol into acetic acid. Contaminated basi also becomes vinegar.

A white variation has become quite popular in Brazil in recent years, where it is the cheapest type of vinegar sold. It is now common for other types of vinegar (made from wine, rice and apple cider) to be sold mixed with cane vinegar to lower the cost.

Sugarcane sirka is made from sugarcane juice in Punjab, India. During summer people put cane juice in earthenware pots with iron nails. The fermentation takes place due to the action of wild yeast. The cane juice is converted to vinegar having a blackish color. The sirka is used to preserve pickles and for flavoring curries.

Grains

Chinese black vinegar is an aged product made from rice, wheat, millet, sorghum, or a combination thereof. It has an inky black color and a complex, malty flavor. There is no fixed recipe, so some Chinese black vinegars may contain added sugar, spices, or caramel color. The most popular variety, Zhenjiang vinegar, originates in the city of Zhenjiang in Jiangsu Province, eastern China.[17] Shanxi mature vinegar is another popular type of Chinese vinegar that is made exclusively from sorghum and other grains. Nowadays in Shanxi province, there are still some traditional vinegar workshops producing handmade vinegar which is aged for at least five years with a high acidity. Only the vinegar made in Taiyuan and some counties in Jinzhong and aged for at least three years is considered authentic Shanxi mature vinegar according to the latest national standard. A somewhat lighter form of black vinegar, made from rice, is produced in Japan, where it is called kurozu.

Rice vinegar is most popular in the cuisines of East and Southeast Asia. It is available in "white" (light yellow), red, and black varieties. The Japanese prefer a light rice vinegar for the preparation of sushi rice and salad dressings. Red rice vinegar traditionally is colored with red yeast rice. Black rice vinegar (made with black glutinous rice) is most popular in China, and it is also widely used in other East Asian countries. White rice vinegar has a mild acidity with a somewhat "flat" and uncomplex flavor. Some varieties of rice vinegar are sweetened or otherwise seasoned with spices or other added flavorings.

Malt vinegar made from ale, also called alegar[18], is made by malting barley, causing the starch in the grain to turn to maltose. Then an ale is brewed from the maltose and allowed to turn into vinegar, which is then aged.[18] It is typically light-brown in color. In the United Kingdom and Canada, malt vinegar (along with salt) is a traditional seasoning for fish and chips. Some fish and chip shops replace it with non-brewed condiment.

According to Canadian regulations, malt vinegar is defined as a vinegar that includes undistilled malt that has not yet undergone acetous fermentation. It must be dextro-rotary and cannot contain less than 1.8 grams of solids and 0.2 grams of ash per 100 millilitres at 20 degrees Celsius. It may contain additional cereals or caramel.[19]

Spirits

The term spirit vinegar is sometimes reserved for the stronger variety (5% to 21% acetic acid) made from sugar cane or from chemically produced acetic acid.[20] To be called "Spirit Vinegar", the product must come from an agricultural source and must be made by "double fermentation". The first fermentation is sugar to alcohol and the second alcohol to acetic acid. Product made from chemically produced acetic acid cannot be called "vinegar". In the UK the term allowed is "Non-brewed condiment".

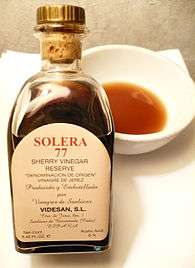

Sherry vinegar is linked to the production of sherry wines of Jerez. Dark mahogany in color, it is made exclusively from the acetic fermentation of wines. It is concentrated and has generous aromas, including a note of wood, ideal for vinaigrettes and flavoring various foods. Wine vinegar is made from red or white wine, and is the most commonly used vinegar in Southern and Central Europe, Cyprus and Israel. As with wine, there is a considerable range in quality. Better-quality wine vinegars are matured in wood for up to two years, and exhibit a complex, mellow flavor. Wine vinegar tends to have a lower acidity than white or cider vinegars. More expensive wine vinegars are made from individual varieties of wine, such as champagne, sherry, or pinot gris.

The term "distilled vinegar" as used in the United States (called "spirit vinegar" in the UK, "white vinegar" in Canada[21]) is something of a misnomer because it is not produced by distillation but by fermentation of distilled alcohol. The fermentate is diluted to produce a colorless solution of 5% to 8% acetic acid in water, with a pH of about 2.6. This is variously known as distilled spirit, "virgin" vinegar,[22] or white vinegar, and is used in cooking, baking, meat preservation, and pickling, as well as for medicinal, laboratory, and cleaning purposes.[20] The most common starting material in some regions, because of its low cost, is malt,[23] or in the United States, corn. It is sometimes derived from petroleum.[24] Distilled vinegar in the UK is produced by the distillation of malt to give a clear vinegar which maintains some of the malt flavour.[23] Distilled vinegar is used predominantly for cooking, although in Scotland it is used as an alternative to brown or light malt vinegar. White distilled vinegar can also be used for cleaning, and some is actually sold specifically for this purpose.

Kombucha

Kombucha vinegar is made from kombucha, a symbiotic culture of yeast and bacteria. The bacteria produce a complex array of bacteria. Kombucha vinegar primarily is used to make a vinaigrette, and is flavored by adding strawberries, blackberries, mint, or blueberries at the beginning of fermentation.

Uses

Culinary

Vinegar is commonly used in food preparation, in particular pickling liquids, and vinaigrettes and other salad dressings. It is an ingredient in sauces, such as hot sauce, mustard, ketchup, and mayonnaise. Vinegar is sometimes used in chutneys. It is often used as a condiment on its own or as part of other condiments. Marinades often contain vinegar. In terms of its shelf life, vinegar's acidic nature allows it to last indefinitely without the use of refrigeration.[25]

Beverages

Several beverages are made using vinegar, for instance Posca in ancient Rome. The ancient Greek oxymel is a drink made from vinegar and honey, and sekanjabin is a traditional Persian drink similar to oxymel. Other preparations, known colloquially as "shrubs", range from simply mixing sugar water or honey water with small amounts of fruity vinegar, to making syrup by laying fruit or mint in vinegar for several days, then sieving off solid parts, and adding considerable amounts of sugar. Some prefer to boil the "shrub" as a final step. These recipes have lost much of their popularity with the rise of carbonated beverages, such as soft drinks.

Diet and metabolism

Small amounts of vinegar (2 to 4 Tablespoons) may reduce post-meal levels of blood glucose and insulin in people with and without diabetes.[26][27][28] Some preliminary research indicates that taking vinegar with food increases satiety and reduces the amount of food consumed, producing a loss in body weight, although this effect remains unconfirmed as of 2018.[26]

Folk medicine

For millennia, folk medicine treatments have used vinegar, but there is no evidence from clinical research to support health claims of benefits for diabetes, weight loss, cancer or use as a probiotic.[26] Some treatments with vinegar pose risks to health.[29] Esophageal injury by apple cider vinegar has been reported, and because vinegar products sold for medicinal purposes are neither regulated nor standardized, such products may vary widely in content and acidity.[30]

Pests

Twenty percent acetic acid vinegar can be used as a herbicide,[31] but acetic acid is not absorbed into root systems so the vinegar will only kill the top growth and perennial plants may reshoot.[32]

Applying vinegar to common jellyfish stings deactivates the nematocysts, although not as effectively as hot water.[33] This does not apply to the Portuguese man o' war, which, although generally considered to be a jellyfish, is not; vinegar applied to Portuguese man o' war stings can cause their nematocysts to discharge venom, making the pain worse.[34]

Household

White vinegar is often used as a household cleaning agent.[36] For most uses, dilution with water is recommended for safety and to avoid damaging the surfaces being cleaned. Because it is acidic, it can dissolve mineral deposits from glass, coffee makers, and other smooth surfaces.[37] Vinegar is known as an effective cleaner of stainless steel and glass. Malt vinegar sprinkled onto crumpled newspaper is a traditional, and still-popular, method of cleaning grease-smeared windows and mirrors in the United Kingdom.[38]

Vinegar can be used for polishing copper, brass, bronze or silver. It is an excellent solvent for cleaning epoxy resin as well as the gum on sticker-type price tags. It has been reported as an effective drain cleaner[39]

Miscellaneous

Most commercial vinegar solutions available to consumers for household use do not exceed 5%. Solutions above 10% require careful handling, as they are corrosive and damaging to the skin.[40]

When a bottle of vinegar is opened, mother of vinegar may develop. It is considered harmless and can be removed by filtering.[41]

Vinegar eels (Turbatrix aceti), a form of nematode, may occur in some forms of vinegar unless the vinegar is kept covered. These feed on the mother of vinegar and can occur in naturally fermenting vinegar.[42]

Some countries prohibit the selling of vinegar over a certain percentage acidity. As an example, the government of Canada limits the acetic acid of vinegars to between 4.1% and 12.3%.[43]

According to legend, in France during the Black Plague, four thieves were able to rob houses of plague victims without being infected themselves. When finally caught, the judge offered to grant the men their freedom, on the condition that they revealed how they managed to stay healthy. They claimed that a medicine woman sold them a potion made of garlic soaked in soured red wine (vinegar). Variants of the recipe, called Four Thieves Vinegar, have been passed down for hundreds of years and are a staple of New Orleans hoodoo practices.[44][45]

A solution of vinegar can be used for water slide decal application as used on scale models and musical instruments, among other things. One part white distilled vinegar (5% acidity) diluted with two parts of distilled or filtered water creates a suitable solution for the application of water-slide decals to hard surfaces. The solution is very similar to the commercial products, often described as "decal softener", sold by hobby shops. The slight acidity of the solution softens the decal and enhances its flexibility, permitting the decal to cling to contours more efficiently.

When baking soda and vinegar are combined, the bicarbonate ion of the baking soda reacts to form carbonic acid, which decomposes into carbon dioxide and water.[46]

See also

References

- ↑ Nakayama T (1959). "Studies on acetic acid-bacteria I. Biochemical studies on ethanol oxidation". J Biochem. 46 (9): 1217–25.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2015), Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function, McGraw-Hill Education, p. 55, ISBN 9814646431

- ↑ Cerezo, Ana B.; Tesfaye, Wendu; Torija, M. Jesús; Mateo, Estíbaliz; García-Parrilla, M. Carmen; Troncoso, Ana M. (2008). "The phenolic composition of red wine vinegar produced in barrels made from different woods". Food Chemistry. 109 (3): 606–615. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.01.013.

- ↑ Cejudo-Bastante, C; Castro-Mejías, R; Natera-Marín, R; García-Barroso, C; Durán-Guerrero, E (2016). "Chemical and sensory characteristics of orange based vinegar". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 53 (8): 3147–3156. doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2288-7. PMC 5055879. PMID 27784909.

- ↑ Coelho, E; Genisheva, Z; Oliveira, J. M; Teixeira, J. A; Domingues, L (2017). "Vinegar production from fruit concentrates: Effect on volatile composition and antioxidant activity". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 54 (12): 4112–4122. doi:10.1007/s13197-017-2783-5. PMC 5643795. PMID 29085154.

- ↑ "Definition of vinegar in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ↑ Holzapfel, Lisa Solieri, Paolo Giudici, editors ; preface by Wilhelm (2009). Vinegars of the world (Online-Ausg. ed.). Milan: Springer. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9788847008663.

Cleopatra dissolves pearls in vinegar [...] vinegar is quite often mentioned, is the Bible, both in the Old and in the New Testament.

- ↑ "What is Fruit Vinegar?". vinegarbook.net. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ↑ Sejo Regular del Vino y Brandy de Jerez (Council regulating the production of Jerezy wine and braef)

- ↑ "Biotechnology in New Zealand" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ "The Vinegar Institute". Versatilevinegar.org. 2008-10-20. Archived from the original on 2010-03-29. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ Das, Bhagwan; Sarin, J. L. (1936). "Vinegar from Dates". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 28 (7): 814. doi:10.1021/ie50319a016.

- ↑ Forbes, Robert James (1971). "Studies in Ancient Technology".

- ↑ "The poetic goodness of pomegranates".

- ↑ Lumpia, Burnt (2009-05-17). "I'm Gonna Git You Suka (Filipino Vinegar)". Burntlumpiablog.com. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ "Balsamic vinegar". BBC Good Food.

- ↑ AsianWeek.com Archived February 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Alegar". Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press. 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ "Vinegar, Division 19". Justice Laws Website, Government of Canada. 27 December 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- 1 2 Sinclair C, International Dictionary of Food and Cooking, Peter Collin Publishing, 1998 ISBN 0-948549-87-4

- ↑ "List of Ingredients and Allergens: Requirements; Exemptions, Prepackaged Products that Do Not Require a List of Ingredients; Standardized vinegars B.01.008(2)(g), FDR". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Allgeier RJ et al., Newer Developments in Vinegar Manufacture, 1960 ("manufacture of white or spirit vinegar"), in Umbreit WW, Advances in Microbiology: Volume 2, Elsevier/Academic Press Inc., ISBN 0-12-002602-3, accessed at Google Books 2009-04-22

- 1 2 Bateman, Michael (2 May 2016). "Bliss and vinegar - why malt makes a pretty pickle: It's time for a revival of a very British condiment". The Independent, Independent Digital News & Media, London, UK. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "CPG Sec. 555.100 Alcohol; Use of Synthetic Alcohol in Foods". Fda.gov. 2014-09-18. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ "Shelf Life of Vinegar". Eatbydate.com.

- 1 2 3 "Vinegar". TH Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University. 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ↑ Shishehbor, F; Mansoori, A; Shirani, F (2017). "Vinegar consumption can attenuate postprandial glucose and insulin responses; a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 127: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2017.01.021. PMID 28292654.

- ↑ Liatis, S; Grammatikou, S; Poulia, K-A; Perrea, D; Makrilakis, K; Diakoumopoulou, E; Katsilambros, N (2010). "Vinegar reduces postprandial hyperglycaemia in patients with type II diabetes when added to a high, but not to a low, glycaemic index meal". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 64 (7): 727. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2010.89. PMID 20502468.

- ↑ Johnston, Carol S.; Gaas, Cindy A. (2006). "Vinegar: medicinal uses and antiglycemic effect". MedGenMed. 8 (2): 61. PMC 1785201. PMID 16926800.

- ↑ Hill, L; Woodruff, L; Foote, J; Barreto-Alcoba, M (2005). "Esophageal Injury by Apple Cider Vinegar Tablets and Subsequent Evaluation of Products". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 105 (7): 1141–4. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.04.003. PMID 15983536.

- ↑ "Spray Weeds With Vinegar?". Ars.usda.gov. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ "Vinegar as herbicide". Cahe.nmsu.edu. 2004-04-10. Archived from the original on 2008-05-04. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ Nomura, J; Sato, RL; Ahern, RM; Snow, JL; Kuwaye, TT; Yamamoto, LG (2002). "A randomized paired comparison trial of cutaneous treatments for acute jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20 (7): 624–6. doi:10.1053/ajem.2002.35710. PMID 12442242.

- ↑ "Portuguese Man 'o Wars and their sting treatment". Cinemaquatics.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ Takanolee, M; Edman, J; Mullens, B; Clark, J (2004). "Home Remedies to Control Head Lice Assessment of Home Remedies to Control the Human Head Louse, Pediculus humanus capitis (Anoplura: Pediculidae)". Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 19 (6): 393–8. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2004.11.002. PMID 15637580.

- ↑ "7 Unexpected Ways to Use Vinegar Around the House". www.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- ↑ "My Environment: Cleaning Products", Ontario Ministry of the Environment

- ↑ "Trade Secrets: Betty's Tips", BBC/Lifestyle/Homes/Housekeeping. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ↑ "95+ Household Uses for Vinegar | Reader's Digest". Rd.com. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ "Conquer Weeds with Vinegar?". Hort.purdue.edu. 2006-03-24. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ "Vinegar Information". Reinhart Foods. 2004-01-01. Archived from the original on 2012-12-28. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ "FDA: Sec. 525.825 Vinegar, Definitions – Adulteration with Vinegar Eels (CPG 7109.22)". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-07-27. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ "Departmental Consolidation of the Food and Drugs Act and the Food and Drug Regulations – Part B – Division 19" (PDF). Health Canada. March 2003. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ↑ Hunter, Robert (1894). The Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Toronto: T.J. Ford. ISBN 0-665-85186-3.

- ↑ Kacirk, Jeffery (2000). The Word Museum:The most remarkable English ever forgotten. Touchstone. ISBN 0-684-85761-8.

- ↑ http://engineering.oregonstate.edu/momentum/k12/march04/index.html

External links

![]()

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Vinegar. |