Victoria line

| Victoria line | |

|---|---|

|

| |

A 2009 stock Victoria line train at Pimlico | |

| Overview | |

| Type | Deep-level |

| System | London Underground |

| Stations | 16 (6 of which are step free) |

| Ridership | 199.988 million (2011/12)[1] passenger journeys |

| Colour on map | Light blue |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1968 |

| Depot(s) | Northumberland Park |

| Rolling stock | 2009 stock, 8 cars per trainset |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 21 km (13 mi) |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) |

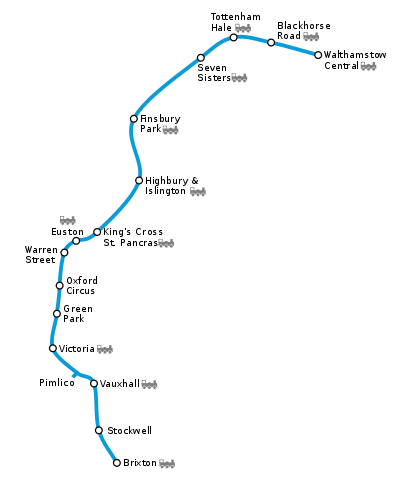

The Victoria line is a London Underground line that runs between Brixton in south London and Walthamstow Central in the north-east, via the West End. It is coloured light blue on the Tube map and is one of two lines to run entirely below ground.[note 1]

Constructed in the 1960s, it was the first entirely new Underground line in London for 50 years and was designed to relieve congestion on other lines, particularly the Piccadilly line and the Charing Cross branch of the Northern line. The first section, from Walthamstow Central to Highbury & Islington, opened in September 1968, with an extension to Warren Street following in December. The line was completed to Victoria station in March 1969, which was opened by Queen Elizabeth II. The southern extension to Brixton opened in 1971, and Pimlico station was added in 1972.

The Victoria line is a deep-level line and has always been operated using automatic train operation, but all trains carry drivers. There are 16 stations on the route, all but Pimlico providing interchanges with other Underground lines or National Rail services. It is used by 200 million passengers each year and is the most intensively used line on the Underground.

History

Planning

The first proposal of a railway in this area appeared on the County of London Plan, published in 1943.[2] in 1948, a working party set up by the British Transport Commission (BTC) proposed a tube railway running from Victoria to Walthamstow,[3] largely based on a 1946 plan for a Croydon-to-Finsbury Park line. The main purpose was to relieve congestion in the central area, which had been identified as a problem since the 1930s.[4] Other benefits were to link the key national railway stations of Victoria, Euston, King's Cross and St. Pancras, and to improve connections between north-east London and the city.[5]

In early 1949, the BTC committee looked at the feasibility of building a deep-level tube that fulfilled these requirements.[6] For the first time a complete cost–benefit analysis was used, to ensure that the line would be built within budget and be profitable.[7] The necessary Private Bill was introduced into Parliament in 1955. It described a line from Victoria to Walthamstow (Wood Street). The intended terminus at Wood Street would have been sited next to the British Rail station there. (There was a proposal, not included in the Bill, for a subsequent extension from Victoria to Fulham Broadway station on the District line, and for the line to terminate at Edmonton instead of Walthamstow.[8][9] Proposals were also made to extend the line as far north as South Woodford or Woodford, to provide interchange with the Central line.)[10] However, in a late decision in 1961, the line was cut back to Walthamstow (Hoe Street) station, which was renamed Walthamstow Central on 6 May 1968 in anticipation of the line's opening.[11][12] The line was planned to use cross-platform interchanges where possible (at Oxford Circus, Euston, Finsbury Park and Walthamstow Central), in order to provide a quick and easy connection between the new line and existing services.[13]

The name "Victoria line" dates back to 1955; other suggestions were "Walvic line" (Walthamstow–Victoria), "Viking line" (Victoria–King's Cross), "Mayfair line" and "West End line".[9] During the planning stages it was known as Route C, and was then named the Victoria line (after Victoria station) by David McKenna, whose suggestion was seconded by Sir John Elliot.[14][9] The board decided that the Victoria line sounded "just right".[9]

Walthamstow – Victoria

The first construction work on the line began in January 1960, when two test tunnels were bored from Tottenham to Manor House under Seven Sisters Road. The tunnels were dug using an experimental "drum digger" rotary shield, powered by hydraulic rams, that could cut away over 60 feet (18 m) per day. The work was completed in July 1961, with the expectation it would be used for the completed Victoria line.[15]

The line gained Government building approval on 20 August 1962, with an expected budget of £56 million, and construction began the following month.[16] The economic boom of the mid-to-late 1950s had faded, and the Government had hoped that building the Victoria line would help reduce unemployment in London.[17] Work began on adapting Oxford Circus station to fit the new line; a cross-platform interchange was provided with the Bakerloo line and a subway link with the Central line.[18] A steel umbrella was erected over the junction in August 1963, in order to build a new ticket hall without disrupting existing traffic.[16] Rolling stock on the line was to be fitted with Automatic Train Operation (ATO), which allowed self-driving of the train based on automatic electrical signals along the track.[19] In March 1964, a £2.25 million contract was awarded to Metro-Cammell for the fleet to be used on the line.[20]

That October, the Northern City Line closed between Drayton Park and Finsbury Park, in order that the latter station could be redesigned for an easy cross-platform interchange between the Victoria and Piccadilly lines. All major contracts had been awarded by 1965, and construction was on track to be completed in 1968.[21] New stations were constructed at Walthamstow Central, Blackhorse Road, Tottenham Hale and Seven Sisters.[22] The station at Blackhorse Road was built on the opposite side of the mainline station (serving the Kentish Town to Barking line) and was not considered an interchange.[23] (This was probably because the Kentish Town-to-Barking service was proposed for closure under the Beeching cuts.)[24] An interchange opened there on 14 December 1981, when surface-line platforms and a connecting overbridge were built on the same side as the tube station, and the original Blackhorse Road station was closed and demolished.[25][26]

The line opened from Walthamstow Central to Highbury & Islington on 1 September 1968.[27][28] There was no initial opening ceremony; instead the normal timetable started.[27] The first train left Walthamstow Central for Highbury & Islington at 7:32 am. The line proved to be immediately popular; over 1,000 tickets were purchased at Highbury & Islington within its first hour of opening.[29]

The next section, from there to Warren Street, opened on 1 December 1968, again without ceremony.[27] The line was formally opened with the completion to Victoria by Queen Elizabeth II on 7 March 1969. At 11:00am, the Queen made the first trip from Green Park to Victoria on a 5d (2.08p) ticket, where she unveiled a plaque.[30][31] In so doing, she was the first reigning monarch ever to ride on the Underground.[32] The line was opened to the general public by 3:00pm, with the route from Walthamstow to Victoria taking around 24 minutes.[30]

Victoria – Brixton

The 3.5-mile (5.6 km) extension from Victoria to Brixton was approved in March 1966, with additional stations at Vauxhall and Stockwell.[21] Preparatory work had already started at Bessborough Gardens near Vauxhall Bridge Road in May 1967.[33] The contract for this extension was awarded on 4 August 1967,[21] while a proposal to build an additional station at Pimlico received Government approval on 28 June 1968.[27] In July, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Edinburgh visited tunnel workings under Vauxhall Park.[34]

The Brixton extension was bored using the older Greathead shield, which although slower allowed easier digging through gravel found on land south of the Thames. It was opened by Princess Alexandra on 23 July 1971, who made a journey from Brixton to Vauxhall.[35][36] Upon opening, it was the first new section of Underground to open south of the Thames since 1926.[35] The final piece of the Victoria line, Pimlico station, opened on 14 September 1972.[37]

London Transport mentioned the possibility of further extensions to Streatham, Dulwich and Crystal Palace, which would ultimately provide a connection to southeast London and Kent. However, no construction work was ever undertaken.[38]

Post-opening

The London Underground (Victoria) Act 1991 allowed for the construction of a new 43-metre (140 ft) underground pedestrian link at Victoria station between the Victoria line platforms and the sub-surface Circle line platforms above.[39] The London Underground (Victoria Station Upgrade) Order 2009 came into force in September that year, authorising the construction of a second 1,930-square-metre (21,000 sq ft) ticket hall at Victoria station.[40]

On 23 January 2014, during upgrade work at Victoria, construction workers accidentally penetrated the signalling room of the Victoria line and flooded it with quick-drying concrete, leading to the suspension of services south of Warren Street.[41] Services resumed the following day after using sugar as a retardant so as to make it easier to shovel the concrete out.[42][43]

A 24-hour Night Tube service on Friday and Saturday nights was due to start in September 2015 on the entire Victoria line[44] but was delayed owing to strike action. The service started in August 2016, with trains running at 10-minute intervals on the whole section of the line.[45]

Design

Every Victoria line station apart from Pimlico and Blackhorse Road was built as an interchange station, and several existing stations were rearranged to allow for cross-platform interchange with the new line. In some cases this was achieved by placing the Victoria line platforms on either side of the existing station; in others, the Victoria line uses one of the older platforms and the existing line was diverted into a new platform.[46] All platforms built for the line are 132.6 metres (435 ft) long.[47] The line has hump-backed stations to allow trains to store gravitational potential energy as they slow down and release it when they leave a station, providing an energy saving of 5% and making the trains run 9% faster.[48][49]

The stations were originally tiled in blue and grey. Each station was decorated with tiled motifs in seating recesses to help identify the station.[50] Some of these motifs were puns; the image for Brixton was simply a ton of bricks.[35] During the construction of the first stage of the Jubilee line in 1979, the original motifs on Green Park station were replaced by motifs matching the new design for the Jubilee line platforms.[51] These were in turn replaced in 2009 by replicas of the original design.

In late 2010 and 2011, platform humps were installed on all Victoria line stations (except Pimlico) in order to provide step-free access to trains.[52] This project was in accordance with the Rail Vehicle Accessibility (Non Interoperable Rail System) Regulations 2010 and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.[53][54] The Victoria line humps resemble in form the Harrington Hump, a ramp type being installed on some mainline stations, but are of a masonry construction.[55]

Service and rolling stock

The Victoria line serves 200 million passengers a year.[56] It is the sixth-most heavily used line on the network in absolute figures, but in terms of the average number of journeys per mile it is by far the most intensively used line.[1] From May 2017, trains run every 100 seconds (slightly less than two minutes) during peak periods, providing 36 trains per hour.[57] In normal service all trains run from Brixton to Seven Sisters, with roughly three out of five continuing to Walthamstow Central.[58]

When the line was opened, it was served by a fleet of 39 1⁄2 eight-car trains of 1967 Tube Stock trains. In the early planning stages of the line an articulated type of rolling stock was considered, but the idea was dropped because of difficulties in transferring the stock to Acton Works for heavy overhauls.[59] With the demise of Acton Works this no longer applies, and the new 2009 tube stock has a wider profile and slightly longer carriages, which preclude it running on other deep-level tube lines. The 1967 stock were later supplemented by a number of cars of 1972 Mark I Tube Stock, transferred from the Northern line and converted to be compatible with the 1967 stock.[60]

Replacement of the 1967 rolling stock began in July 2009 as part of Transport for London's 5-year £10 billion redevelopment project.[61] A new fleet of 47 eight-car trains, the 2009 Tube Stock, were built by Bombardier Transportation.[62] The first prototypes began testing in 2008. The main fleet began to be introduced in 2009 and the majority of trains were operational along the line by the following year. The last of the 1967 stock trains ran on 30 June 2011, after which the whole service was provided by 2009 stock.[63]

On opening, the Victoria line was equipped with a fixed-block Automatic Train Operation system (ATO); the train operator closed the train doors and pressed a pair of "start" buttons and, if the way ahead is clear, the ATO drives the train at a safe speed to the next station. At any point, the driver could switch over to manual control in case the ATO failed.[29] This system, which operated until 2012, made the Victoria line the world's first full-scale automatic railway.[note 2]

The Victoria line runs faster trains than other Underground lines because of fewer stops, ATO running and modern design.[67][68] Train speeds can reach up to 50 miles per hour (80 km/h). A popular way for locals in north London to visit the West End is to take the Northern line onto the Bank branch, change across platforms at Euston, and continue on the faster Victoria line trains.[67] The original signalling has now been replaced with a more modern ATO system from Westinghouse Rail Systems[61] incorporating 'Distance to Go Radio' and more than 400 track circuits. LUL claims that this is the world's first ATO-on-ATO upgrade.[62] The new system allowed a revised timetable to be introduced from February 2013, initially allowing up to 33 trains per hour instead of 27.[69] This in combination with new, faster trains increased the line's capacity overall by 21%,[61] equivalent to an extra 10,000 passengers per hour.[63]

Facilities

Step-free access

Tottenham Hale, King's Cross St. Pancras, Green Park, Victoria, Vauxhall and Brixton have step-free access from street to train.[70][71][72][73][74] Platform humps have been installed at all stations on the Victoria line (except Pimlico) to provide level access to the trains, improving access for customers with mobility impairments, luggage or pushchairs.[75] Step-free routes are available between the Victoria and other lines at most interchange stations.

Ventilation

Around 50 ventilation shafts were created during the construction phase of the line.[76] Midpoint tunnel ventilation shafts remain between each station. Special "local arrangements" are in place should it be necessary to evacuate passengers from a Victoria line train out of Netherton Road emergency escape shaft.[77] Planning permission for the shaft at Ferry Lane was granted on 11 January 1968.[78]

By mid-2009, trial boreholes for a cooling system at Green Park station had taken place, with additional boreholes being scheduled to be created during the end of 2009.[79] In 2010, Engineering & Technology reported that 200 litres (44 imp gal) of water per second was being pumped through Victoria station from the River Tyburn, through heat-exchangers and into the River Thames, for the cooling system.[80]

Between 2009 and 2014, thirteen ventilation shafts were scheduled to be refurbished. In the first phase, during tranche 1, the air shafts for replacement were Drayton Park, Gillingham Street, Moreton Terrace, Pulross Road, Somerleyton Road and Tynemouth Road.[81] In tranche 2, for the second phase, were scheduled those at Cobourg Street, Dover Street, Gibson Square, Great Titchfield Street, Isledon Road, Kings Cross, Palace Street and Rita Road.[81]

By 2009, changes at Cobourg Street were in the planning stage, with demolition work at Moreton Terrace, Somerleyton Road and Drayton Park shafts having taken place.[79] Original planning permission for Netherton Road shaft had been granted on 8 September 1967.[82] On 31 March, the demolition and rebuilding of Netherton Road shaft was allowed as permitted development.[83][84]

Depot

The line's service depot is at Northumberland Park. It acts as the service and storage area for trains, and is the only part of the Victoria line above ground. Trains access the depot by a tunnelled branch line to the north of Seven Sisters.[85]

The depot opened with the first stage of the line in September 1968. It is next to Northumberland Park railway station, on Tottenham Marshes in the London Borough of Haringey, over a mile from the main Victoria line. When built, it was 900 feet (270 m) long and had working space for 22 eight-car trains.[23] As part of Transport for London's tube upgrade scheme, the depot has been expanded and upgraded to accommodate the fleet of 2009 Tube Stock trains.[86][87]

Future

When the Victoria line was built, budget restrictions meant that station infrastructure standards were lower than on older lines and on later extension projects.[17] Examples include narrower than usual platforms and undecorated ceilings at Walthamstow Central, Blackhorse Road and Tottenham Hale, affecting lighting levels.[88]

The line was purposefully built with less escalators than other lines as a cost saving exercise.[89] The lack of a third escalator linking station entrances to platforms can cause severe congestion at peak times. At most stations there is a concrete staircase between the up and down escalators; the space it occupies provides potential for an additional escalator to be installed, as was done at Brixton (in 2004) and Vauxhall (in 2006).[61] There have been station closures, for safety reasons, when escalators have been unserviceable.[90]

Supporters of Tottenham Hotspur (and the club itself) have campaigned for a surface station to be built next to Northumberland Park Station, adjacent to the line's depot. This would improve the football ground's transport links, which are seen as essential in order for the club to redevelop its ground and increase capacity. The plans stalled because Network Rail owns the necessary land and needs it for its own expansion projects.[91][92] It was announced by Haringey Council in its 2012 A Plan for Tottenham report that there was "potential for a Victoria Line extension to Northumberland Park".[93]

Crossrail 2, also known as the Chelsea-Hackney line, is a planned but not funded project to build an additional route across central London between Victoria and King's Cross St. Pancras tube station. This would be intended to relieve congestion on the Victoria line.[94]

There have been proposals to extend the line one stop southwards from Brixton to Herne Hill. Herne Hill station would be on a large reversing loop with one platform. This would remove a critical capacity restriction by eliminating the need for trains to reverse at Brixton.[95] The Mayor of London's 2020 Vision, published in 2013, proposed extending the Victoria line "out beyond Brixton" by 2030.[96]

Stations

Victoria line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Detailled London transport map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station | Image | Opened | Victoria line service began | Interchanges | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walthamstow Central | 26 April 1870[97] | 1 September 1968 |

London Overground |

51°34′59″N 000°01′11″W / 51.58306°N 0.01972°W | |

| Blackhorse Road | 19 July 1894[25] |

London Overground |

51°35′13″N 000°02′29″W / 51.58694°N 0.04139°W | ||

| Tottenham Hale | 15 September 1840[98][TH] |

Mainline trains |

51°35′18″N 000°03′35″W / 51.58833°N 0.05972°W | ||

| Seven Sisters | 22 July 1872[99] |

London Overground, mainline trains |

51°34′56″N 000°04′31″W / 51.58222°N 0.07528°W | ||

| Finsbury Park | 1 July 1861[100][FP] |

Piccadilly line (CPI),[23] mainline trains |

51°33′53″N 000°06′23″W / 51.56472°N 0.10639°W | ||

| Highbury & Islington | 26 September 1850[101] |

Great Northern trains to Welwyn Garden City (CPI),[102] London Overground |

51°32′45″N 000°06′18″W / 51.54583°N 0.10500°W | ||

| King's Cross St. Pancras | 10 January 1863[103] | 1 December 1968 |

Northern (Bank branch), Piccadilly, Circle, Metropolitan, and Hammersmith and City lines; mainline trains |

51°31′49″N 000°07′27″W / 51.53028°N 0.12417°W | |

| Euston | 12 May 1907[104] |

Northern line (CPI with Bank branch),[30] London Overground, mainline trains |

51°31′42″N 000°07′59″W / 51.52833°N 0.13306°W | ||

| Warren Street | 22 June 1907[104] |

Northern line (Charing Cross branch) |

51°31′29″N 000°08′18″W / 51.52472°N 0.13833°W | ||

| Oxford Circus | 30 July 1900[105] | 7 March 1969 |

Bakerloo (CPI)[30] and Central lines |

51°30′55″N 000°08′30″W / 51.51528°N 0.14167°W | |

| Green Park | 15 December 1906[106] |

Piccadilly and Jubilee lines |

51°30′24″N 000°08′34″W / 51.50667°N 0.14278°W | ||

| Victoria | 1 October 1860[107] |

Circle and District lines, mainline trains |

51°29′48″N 000°08′41″W / 51.49667°N 0.14472°W | ||

| Pimlico | 14 September 1972[108] | N/A | 51°29′22″N 000°08′00″W / 51.48944°N 0.13333°W | ||

| Vauxhall | 11 July 1848[107] | 23 July 1971 |

Mainline trains, London River Services (St George Wharf Pier)[109] |

51°29′07″N 000°07′22″W / 51.48528°N 0.12278°W | |

| Stockwell | 4 November 1890[110] |

Northern line (CPI)[35] |

51°28′21″N 000°07′20″W / 51.47250°N 0.12222°W | ||

| Brixton | 23 July 1971[111] |

Mainline trains (within 100 metres' walking distance) |

51°27′45″N 000°06′54″W / 51.46250°N 0.11500°W | ||

| SS Seven Sisters is the only station on the line with more than 2 platforms. The third is used as a holding platform for trains that terminate their journeys from Brixton at Seven Sisters instead of at Walthamstow. This third platform allows access to the Northumberland Park depot. |

| TH Opened as Tottenham, renamed on 1 December 1968.[98] |

| FP Opened as Seven Sisters Road (Holloway), renamed 15 November 1869.[100] |

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The exception is a connection not used by passengers between Seven Sisters and the line's depot at Northumberland Park, position: 51°36′04″N 000°03′11″W / 51.60111°N 0.05306°W

- ↑ Although the system was tested on the Tube on a smaller scale before that, initially on a short section of the District line; then a larger trial was carried out on the Central line between Woodford and Hainault.[64][65][66]

References

Citations

- 1 2 "LU Performance Data Almanac". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 143.

- ↑ Horne 1988, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Wolmar 2012, p. 301.

- ↑ HMSO 1959, p. 10.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 148.

- ↑ Wolmar 2012, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Cooke, B.W.C., ed. (April 1955). "Proposed New London Underground". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 101 no. 648. London. pp. 279–281.

- 1 2 3 4 Day & Reed 2010, p. 153.

- ↑ "Public Passenger Transport, London". Hansard. 18 December 1963.

- ↑ Horne 1988, p. 15.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 240.

- ↑ HMSO 1959, p. 13.

- ↑ Klapper 1976, p. 123.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 156.

- 1 2 Day & Reed 2010, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 Martin 2012, p. 235.

- ↑ HMSO 1959, p. 36.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 161.

- 1 2 3 Day & Reed 2010, p. 163.

- ↑ HMSO 1959, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Day & Reed 2010, p. 167.

- ↑ "Gospel Oak to Barking Renaissance". Rail Engineer. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- 1 2 Butt 1995, p. 36.

- ↑ "Barking – Gospel Oak Line User Group E-Bulletin" (PDF). 27 April 2012. p. 14. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Day & Reed 2010, p. 166.

- ↑ "London's new tube starts work". Modern Railways. Vol. XXIV no. 241. Shepperton, Middlesex: Ian Allan Ltd. October 1968. p. 532.

- 1 2 "Busy start for Victoria Line". The Times. London. 2 September 1968. p. 3. Retrieved 12 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 Day & Reed 2010, p. 168.

- ↑ "Victoria Line". The Times. London. 7 March 1969. p. X. Retrieved 13 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "150 Facts for 150 Years of the Tube". The Independent. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Seeing Red Over A Green". The Times. London. 24 May 1967. p. 2. Retrieved 12 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Picture Gallery". The Times. London. 13 July 1968. p. 3. Retrieved 12 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 Day & Reed 2010, p. 171.

- ↑ "Picture Gallery". The Times. London. 24 July 1971. p. 2. Retrieved 14 April 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 172.

- ↑ Warman, Christopher (23 March 1973). "GLC Conservatives hope to put north Kent towns on Tube". The Times. London. p. 6. Retrieved 13 September 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "London Underground (Victoria) Act 1991" (Statutory Instrument). The National Archives. 27 June 1991. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "The London Underground (Victoria Station Upgrade) Order 2009" (Statutory Instrument). The National Archives. 28 August 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "Victoria Tube line part shut hit by wet concrete flood". BBC News. 23 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Underground blunder: 'sugar used to slow concrete setting'". The Daily Telegraph. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ "Why sugar helped remove Victoria Line concrete flood". The Daily Telegraph. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Night Tube". The Future of the Tube. Transport for London. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Night Tube". Transport for London. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ "2009 Tube Stock on Track" (PDF). London Underground Railway Society. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ MacKay, David J.C. (2008). Sustainable Energy - without the hot air (Free full text). ISBN 978-1-906860-01-1.

- ↑ "This Northern Line Cheat Will Save You Minutes On Every Commute". Londonist. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 169.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, p. 180.

- ↑ "Tube Update Plan — Victoria". Transport for London. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ "Victoria Line Platform Humps and RVAR". Livis. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ "Victoria Line Platform Humps and RVAR" (PDF). Livis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ "Creating Step Free Access for All" (PDF). Marshalls. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ "London Underground's Victoria Line marks 50th birthday". BBC News. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ Dan Templeton (26 May 2017). "New Victoria Line timetable increases frequency". International Railway Journal. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "Journey Planner timetables". Transport for London. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ Day 1969, p. 81.

- ↑ Hardy 2002, pp. 10,12.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tube Upgrade Plan: Victoria line". Transport for London. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- 1 2 Waboso, David (December 2010). "Transforming the tube". Modern Railways. London. pp. 42–45.

- 1 2 "Final 1960s stock withdrawn from Victoria Line". Rail. Peterborough. 10 August 2011. p. 14.

- ↑ "Driverless metros poised to expand". Railway Gazette International. 1 March 2000. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

These trials matured into 'attended ATO'. London's Victoria line was the first into revenue service on 1 September 1968, with Philadelphia's Lindenwold line close behind in January 1969.

- ↑ "Automatic Train Operation on the Victoria Line". The Tube Professionals' Rumour Network. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ↑ "House of Lords Hansard for 25 Feb 1998 (pt 9)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. 25 February 1998. col. 747.

- 1 2 Martin 2012, p. 236.

- ↑ HMSO 1959, p. 12.

- ↑ "Victoria line customers have most intensive train service in the country" (Press release). Transport for London. 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Transport for London (December 2017). Standard Tube Map (PDF) (Map). Not to scale. Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2018.

- ↑ "Step free Tube Guide" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "Avoiding stairs Tube guide" (PDF). Transport for London. July 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2018.

- ↑ "£36m upgrade of Vauxhall Tube station reaches half way". 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "Victoria". Improvements and Projects. Transport for London. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "Victoria line". What We've Done. Transport for London. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ Dunton, C. E.; Kell, J.; Morgan, H. D. (1 June 1966). "Discussion on Paper No. 6845". Victoria Line: experimentation, design, programming, and early progress (PDF). ICE Proceedings (Report). 34. Institution of Civil Engineers. pp. 447–460. ISSN 1753-7789.

- ↑ London Underground (28 April 2002). "Detrainment of Passengers" (PDF). Standards. Tc100. The Independent (02): 1.

- ↑ "OLD/1968/0211". Online Planning Services. Haringey Council. 11 January 1968. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

Land At Ferry Lane: Construction of new fan house form Victoria Line.

- 1 2 London Underground Limited (20 May 2009). Parry, Richard, ed. Performance Report to the Rail and Underground Panel (PDF). Managing Director's Report – London Underground (Report). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Douglas, Lawrie (2 July 2010). "Air-conditioning of London Underground — reality or dream?". Engineering & Technology. Institution of Engineering and Technology. 5 (10).

- 1 2 Klettner (24 January 2008). "Underground keeps its cool". Construction News. Event occurs at Andrea. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "OLD/1967/0517". Online Planning Services. Haringey Council. 8 September 1967. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

Construction of new ventilation shaft and emergency staircase for Victoria Line.

- ↑ Urban Environment Directorate (6 April 2004). "01/03/2009 to 31/03/2009". HGY/2009/0151: LUL Mid-Tunnel Vent Shaft, Netherton Road N15 (PDF). Planning Applications Decided (Report). Haringey Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

Demolition and rebuilding of existing headhouse in order to upgrade existing cooling system to Victoria Line.

- ↑ "HGY/2009/0151". Online Planning Services. Haringey Council. 31 March 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

Demolition and rebuilding of existing headhouse in order to upgrade existing cooling system to Victoria Line.

- ↑ "Visit to Northumberland Park Depot". Institution of Railway Operators. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ Waboso, David (December 2010). "Transforming the tube". Modern Railways. London. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ "London Underground Major Regeneration Scheme". Railway Technology. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Victoria Line". Railway Magazine. Vol. 115. 1969. p. 246.

- ↑ "I'm very worried that Crossrail doesn't have enough escalators". CityMetric. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ "Highbury & Islington closed for escalator repairs" (PDF). Transport for London. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ↑ "Mayor's support for Tube extension". BBC News. 19 March 2003. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Have/would we consider extending the Victoria line to Northumberland Park?". Transport for London. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ↑ Strickland, Alan; Kober, Claire; Vanier, Bernice; Lipton, Stuart; Lammy, David; Fletcher-Smith, Fiona; Head, Paul; Campling, Andrew; Travers, Tony; Boylan, Brian; Girt, Matthew (26 July 2012). A Plan for Tottenham (PDF) (Report). Haringey Council. p. 10. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

potential for a Victoria Line extension to Northumberland Park

- ↑ "Crossrail 2 factsheet: Victoria station – TfL Consultation" (PDF). Transport for London. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ "Unlocking Herne Hill and the Kent route to the City". London Reconnections. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "(Click on the arrow pointing south east from Brixton and then, on the popup, click on "more")". Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 121.

- 1 2 Butt 1995, p. 232.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 209.

- 1 2 Butt 1995, p. 208.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 128.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2010, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 134.

- 1 2 Butt 1995, p. 92.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 179.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 81.

- 1 2 Butt 1995, p. 238.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 185.

- ↑ "MBNA Thames Clippers Timetable" (Timetable). 21 May 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 220.

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 45.

Sources

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2010) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-341-9.

- Day, John R. (1969). The Story of the Victoria Line. Westminster: London Transport. 968/2719 RP/5M.

- Hardy, Brian (2002) [1976]. London Underground Rolling Stock (15th ed.). Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-263-1.

- Horne, M.A.C. (1988). The Victoria Line: A short history. London: Douglas Rose. ISBN 978-1-870354-02-8.

- Klapper, Charles (1976). London's lost railways. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. OCLC 487714609.

- Martin, Andrew (2012). Underground, Overground. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-846-68478-4.

- Wolmar, Christian (2012) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0-857-89069-6.

- The Victoria Line : Report by the London Travel Committee to the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1959.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

Route map:

- "Victoria Line: Report Number One" on YouTube

- "Opening of the Victoria Line". British Pathe. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "Victoria line". Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides. 30 December 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "Automatic Train Operation on the Victoria Line". Tube Prune. 15 March 2003. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "BCV (Bakerloo, Central & Victoria) Upgrade". Alwaystouchout.com. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "Victoria Line Underground Stations – Facts, Trivia And Impressions". 22 October 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Victoria line on Twitter

- London Transport Museum Poster Archive – images of the station tiling motifs: