Vanguard TV3

Vanguard TV3 satellite. | |

| Mission type | Earth science |

|---|---|

| Operator | Naval Research Laboratory |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | NRL / Bell Laboratories |

| Launch mass | 1.36 kilograms (3.0 lb)[1] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | December 6, 1957, 16:44:34 UTC |

| Rocket | Vanguard TV3 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-18A |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Medium Earth |

| Perigee | 654 kilometers (406 mi) |

| Apogee | 3,969 kilometers (2,466 mi) |

| Inclination | 34.2° |

| Period | 134.2 minutes |

| Epoch | Planned |

Vanguard TV3, also called Vanguard Test Vehicle Three was the first attempt of the United States to launch a satellite into orbit around the Earth. Vanguard 1A was a small satellite designed to test the launch capabilities of the three-stage Vanguard and study the effects of the environment on a satellite and its systems in Earth orbit. It was also to be used to obtain geodetic measurements through orbit analysis. Solar cells on Vanguard 1A were manufactured by Bell Laboratories.

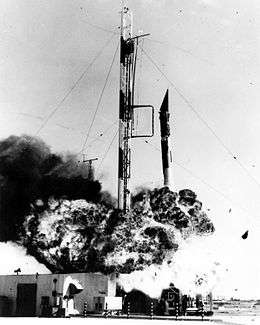

At its launch attempt on December 6, 1957, at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, the booster ignited and began to rise, but about two seconds after liftoff, after rising about four feet (1.2 m), the rocket lost thrust and fell back to the launch pad. As it settled the fuel tanks ruptured and exploded, destroying the rocket and severely damaging the launch pad. The Vanguard satellite was thrown clear and landed on the ground a short distance away with its transmitters still sending out a beacon signal. The satellite was damaged, however, and could not be reused. It is now on display at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.[1]

The exact cause of the accident was not determined with certainty, but it appeared that the fuel system malfunctioned. Other engines of the same model were modified and did not fail.

Satellite construction project

The history of the Vanguard TV3 project dates back to the International Geophysical Year (IGY). This was an enthusiastic international undertaking that united scientists globally to conduct planet-wide geophysical studies. The IGY guaranteed free exchange of information acquired through scientific observation which led to many important discoveries in the future.[2] Orbiting a satellite became one of the main goals of the IGY. As early as July 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower announced, through his press secretary, that the United States would launch "small, unmanned, earth-circling satellites as part of the U.S. participation in the I.G.Y." [3] On September 9, 1955, the United States Department of Defense wrote a letter to the secretary of the Navy authorizing the mission to proceed. The US Navy had been assigned the task of launching Vanguard satellites as part of the program. Project Vanguard had officially begun.[4]

Satellite design

The payload of the TV3 was very similar to the later Vanguard 1. It was a small aluminium sphere, 15.2 cm in diameter and with a mass of 1.36 kg. It carried two transmitters: a 10-mW, 108-MHz transmitter powered by a mercury battery, and a 5-mW, 108.03-MHz transmitter powered by six solar cells mounted on the body of the spacecraft. Using six small aerial antennae mounted on its body, the satellite primarily transmitted engineering and telemetry data, but the transmitters were also used to determine the total electron content between the satellite and the ground stations. Other instruments in the satellite's design included two thermistors, which were used to measure the satellite's internal temperatures for the purpose of tracking its thermal protection's effectiveness. Although the satellite was damaged beyond reuse capability during the crash, it was still transmitting after the incident.[1]

Launch vehicle design

The Vanguard TV3 utilized a three-stage launch vehicle known as the Vanguard designed to send the satellite into orbit around the earth. The fins were removed from the rocket as a way to reduce the drag, but instead, a big motor is mounted in gimbals which allow it to pivot and direct its thrust for steering. The same feature is similarly rigged for the second and third stages of the rocket as well.[5]

The first stage allows the rocket to rise vertically under the powerful thrust of burning liquid oxygen, ethanol, gasoline and silicone oil which propels the vehicle at a rate of 4000 miles per hour, lifting the satellite through the denser layers of the atmosphere in 130 seconds. At this point, the second stage burns its fuel carrying it away from the stage one motor and tanks. The satellite rises to an altitude of 300 miles above the earth. The flight path has been programmed to change from a vertical into a more horizontal course. Then, the third stage takes over to provide spin and the final boost, shoving stage three horizontally into orbit at the rate of 18000 miles per hour. The satellite slowly disengaged from the third-stage rocket where at this speed, the satellite falls toward earth at the same rate earth's surface curves away from it. As a result, the satellite's distance from the earth remains about the same.[6]

Cause of failure

The exact cause of the accident was not determined with certainty due to limited telemetry instrumentation at this early phase,[7] but Martin-Marietta concluded that low fuel tank pressure during the start procedure allowed some of the burning fuel in the combustion chamber to leak into the fuel system through the injector head before full propellant pressure was obtained from the turbopump. GE on the other hand argued that the problem was a loose fuel connection, and the actual truth appeared to be somewhere in-between. Investigation concluded that tank and fuel system pressure were slightly lower than nominal, which resulted in insufficient pressure in the injector head. As a result, hot combustion gas backed up into the injector head and caused a large pressure spike. The injector rings completely burned through, followed by rupture of the combustion chamber. At T+1 second, a shock wave in the thrust section of the booster ruptured a fuel feed line, completely terminating engine thrust. GE technicians had failed to catch this design flaw during testing and a temporary fix was made by increasing tank pressure. Eventually, a further modification was made by using ethane gas to increase fuel force and prevent rough start transients.[8] The X-405 engine did not fail again on subsequent launches and static firing tests.

Reaction

As a result of the launch failure, trading in the stock of the Martin Company, prime contractor for the project, was temporarily suspended by the New York Stock Exchange.[7]

Newspapers in the United States published prominent headlines and articles noting the failure including plays on the name of the Russian satellite, Sputnik, such as "Flopnik",[9] "Kaputnik",[10] "Oopsnik", and "Stayputnik".[11] The failure, reported in international media, was a humiliating loss of prestige for the United States, which had presented itself to the world as the leader in science and technology. The Soviet Union, the United States' rival in the Cold War, exploited the disaster.[12][13] A few days after the incident, a Soviet delegate to the United Nations inquired solicitously whether the United States was interested in receiving aid earmarked for "undeveloped countries".[14]

The concurrent project Explorer 1 proved successful a few weeks later, on 31 January 1958.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 "Vanguard TV3". NSSDC Master Catalog. NSSDC, NASA. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ↑ Lina Kohonen. "The Space race and Soviet utopian thinking" Sociological Review; Vol. 57, May 2009, page 114

- ↑ John P. Hagen, "The Viking and the Vanguard", in Technology and Culture, Vol. 4, No. 4, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press), Autumn 1963, page 437)

- ↑ John P. Hagen, "The Viking and the Vanguard", in Technology and Culture, Vol. 4, No. 4, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press), Autumn 1963, page 439)

- ↑ Fred L. Whipple & J. Allen Hynek, "Stand by for Satellite Take-off" in Popular Mechanics Magazine, H.H. Windsor Jr, Illinois: the Hearst Corporation, July 1957 issue, page 66.

- ↑ Fred L. Whipple & J. Allen Hynek, "Stand by for Satellite Take-off" in Popular Mechanics Magazine, H.H. Windsor Jr, Illinois: the Hearst Corporation, July 1957 issue, page 67.

- 1 2 McLaughlin Green, Constance; Lomask, Milton (1970). "Chapter 11: From Sputnik I to TV-3". Vanguard - A History. NASA. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ↑ https://www.scribd.com/document/46133829/The-Vanguard-Satellite-Launching-Vehicle-an-Engineering-Summary

- ↑ Sparrow, Giles (2007). Space Flight. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7566-2858-X.

- ↑ Burrows, William E. (1999). This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age. Modern Library. p. 205. ISBN 0-375-75485-7.

- ↑ Alan Boyle (1997-10-04). "Sputnik started space race, anxiety". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ↑ Catchpole, John (2001). Project Mercury: NASA's First Manned Space Program. p. 56. ISBN 1-85233-406-1.

- ↑ Jones, Thomas (2002). "Early Frustrations: Project Kaboom (A.K.A Vanguard)". Complete Idiots Guide to NASA. ISBN 0-02-864282-1.

- ↑ Charles A. Murray & Catherine Bly Cox, in Apollo: The Race to the Moon. (United States of America: Simon & Schuster Inc.), 1989, page 23-24)

- ↑ McDonald, Naugle (2008). "Discovering Earth's Radiation Belts: Remembering Explorer 1 and 3". NASA History. American Geological Union. 89 (39). Retrieved 2017-12-06.

External links

- YouTube - Vanguard (Flopnik) (in black and white)

- YouTube - Vanguard TV3 Failed Rocket Launch (in color)

- Google Newspapers - The Ottawa Citizen - "US fails to fire Satellite"